Stop saying "there is no decoupling". There is!

Decoupling will take time, and it won't look like the Iron Curtain, but it's happening.

Let’s circle back to the decoupling debate. About four months ago, I noticed a number of commentators — particularly at The Economist — claiming that decoupling is fake. I thought they made a lot of unjustified assumptions and employed some loose, hand-wavey reasoning, as I tried to explain in this post:

Here’s a brief recap. Some of the decoupling narrative has focused on the fact that the U.S. is getting fewer of its imports from China in recent years:

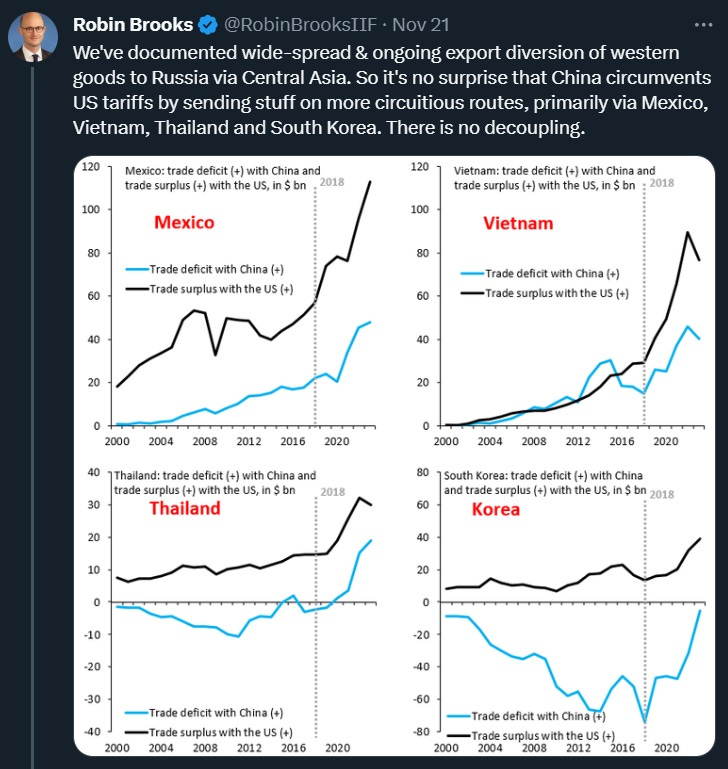

The doubters basically say that this is an illusion, and that what’s really happening is that China is just exporting goods to Mexico, Vietnam, etc., and that these countries are just sending these goods on to the U.S., making it look like Chinese exports to the U.S. are falling even though they’re actually just being re-routed through other countries. For example, here’s Robin Brooks of the Institute of International Finance, boldly proclaiming that “there is no decoupling”:

Now, this is fairly weak and hand-wavey evidence for such a bold, sweeping claim. There’s no guarantee that every dollar of goods that Mexico or Vietnam has started importing from China since 2018 is being re-exported to America; maybe some of those Chinese imports are being consumed locally. Also, these are net trade numbers, not gross numbers — Mexico’s trade deficit with China doesn’t only represent Mexican imports from China, it also depends on Mexican exports to China. There’s no reason to think these net numbers represent total flows of goods.

Here’s a simple example. Suppose for the sake of argument that in 2018, America is buying laptops made in China. Now America stops buying laptops from China and starts buying laptops made in Mexico. And suppose China now sells its laptops to Mexico instead of to the U.S. In this example, Mexico’s trade deficit with China goes up and its trade surplus with the U.S. goes up too. But this represents total decoupling, because America is no longer reliant on Chinese manufacturers for its laptops. If a war cut off both Mexico and America from Chinese production tomorrow, America could continue to buy laptops made in Mexico. (As for Mexico in this example, it would suddenly be deprived of Chinese-made laptops, so it would have to either buy fewer laptops or expand its own production lines.) China observer Desmond Shum believes that something along these lines is actually happening.

Anyway, this simple example shows why simply looking at these overall flows doesn’t tell you whose consumers are dependent on whose production lines. And you can apply a similar counterexample to any argument like this that’s based on trade deficits and surpluses.

The Economist’s latest article brings significantly better data. They cite a new BIS paper by Han Qiu, Hyun Song Shin, and Leanne Si Ying Zhang, which shows that supply chains that begin in China and end in America are lengthening. In other words, it’s true that the U.S. is buying a lot more Mexican- and Vietnamese-made products that contain a lot of Chinese parts and components. Yes, this is a real thing that is happening.

But the Economist article makes a mistake here:

Analysis by the Bank for International Settlements shows supply chains are growing longer and more complicated, while their origins remain mostly unchanged. (emphasis mine)

The BIS paper finds no such thing. Instead, it finds that there has been some degree of on-shoring of production:

Comparing across the two sample periods, we see signs of some on-shoring…The share of direct (one-step) cross-country [value chain] linkages in the total linkages declined between December 2021 and September 2023, indicating greater on-shoring.

Qiu et al. do find that the network density of global value chains hasn’t increased, meaning that suppliers are generally not increasing their number of customers, and customers generally aren’t increasing their number of suppliers. That’s an important thing to keep an eye on, but it’s not the same as saying that China’s role in the production of the goods that Americans buy remains unchanged.

Quantifying U.S. dependence on China requires even more detailed data — it requires measurement of value-added trade. That data is difficult to collect, and comes out with about a 5 or 6 year lag. So we don’t know how much true trade decoupling has happened yet. That said, there are some people working on estimating this, and their conclusion is that some degree of actual decoupling is happening:

The share of US imports coming from China has dropped by 2-3 percentage points since Washington imposed large-scale tariffs on Chinese goods in 2018, rather than the around 8 percentage-point drop shown in US government data, Gavekal Dragonomics analyst Thomas Gatley wrote in a note.

The decline shown in official US data is partly the result of Chinese goods being rerouted through Southeast Asia and other third countries, and under-invoicing by US importers to reduce the impact of tariffs.

“Partly” is a far cry from “entirely”. Yes, true trade decoupling isn’t as high as the headline numbers suggest, but a 2-3 percentage point decrease isn’t nothing — remember, this is 2-3 percentage points out of a total of 21 percentage points or something like that.

But in fact there’s a far bigger reason why the decoupling-doubters are missing the point here. They seem to have the wrong idea about what decoupling should look like.

The doubters seem to believe that decoupling should look like the fall of an Iron Curtain between the U.S. and China — a rapid cutoff of trade between the two countries, and a separation of the world into two largely unconnected trading blocs. In fact, there are some research papers that model decoupling as exactly this sort of total separation.

But frankly, those are not very useful papers. The scenario they model was simply never going to happen — the global trading network is far too entrenched and far too complex to suddenly split itself in two, even in the event of a major war. By focusing on that extreme fantasy scenario, the authors of those papers missed a chance to predict the impact of much more realistic scenarios.

Anyway, we do have a rough idea of what decoupling would realistically look like. And it looks sort of like what’s happening right now.

First, we’d expect to see a decoupling of foreign direct investment long before we saw a decoupling in actual trade. Right now, a lot of companies in the U.S. and Europe still make products in China that they then sell to U.S. and European customers — the most famous example being Apple. If Western companies that sell to Western customers really wanted to get their supply chains out of China, the first thing we’d see would be a collapse of FDI into China.

And guess what? That’s exactly what we’re seeing right now. Money flowing into China appears to be falling, but so much money is exiting China that net FDI into the country has almost completely collapsed:

In the most recent quarter, so much money flowed out of China that net FDI actually went negative for the first time since they started keeping track!

And here is a graph from the always-excellent Rhodium Group, showing the changes in announcements of greenfield FDI (i.e., new factories and offices):

India’s spike is particularly eye-catching. This fits with reports that Western retailers like Wal-Mart are now looking to India as a major source of cheap goods.

The decoupling-doubters seem to be completely ignoring investors’ stampede for the exits. No, the reversal of FDI into China doesn’t necessarily mean that Western economies will become less reliant on Chinese production, but it shows that multinational companies are clearly worried about the risks of staying in China.

And if they’re worried about the risks of staying in China, they’re also going to worry about the risks of sourcing products from Vietnam and Mexico and India if those products are just stuffed with Chinese-made components. And so they will seek to pressure their Vietnamese and Mexican and Indian suppliers to diversify component supply chains out of China as well.

The Vietnamese and Mexican and Indian suppliers will also want to get their component sourcing out of China, as will the Vietnamese and Mexican and Indian governments. They will want to do the component manufacturing themselves, because that will make them a lot more money. Here’s how supply chains tend to work:

First, some companies make fat profit margins designing products and building the tricky, high-tech components.

They then ship those components to a poorer country, where low-paid workers slap the components together into a product, making low profit margins.

Those assemblers then ship the final product to companies in a consumer country, who make fat profit margins selling the products to rich local consumers and offering support services for the products.

This is known as the “smile curve”, and for a long time, China was the poor country stuck in the middle of the chain, doing the low-value assembly work. But in the late 2000s and 2010s, Chinese companies gradually moved up the value chain, graduating from low-value assembly to high-value component manufacturing. Subramanian et al. (2023) write:

China rose as a mega-trader by integrating the middle of value chains, importing goods to reexport…It is now producing most of its inputs, thereby reducing the “traded-ness” of manufactured goods and increasing its share of global manufacturing.

China’s onshoring of component production was so vast and so dramatic that Subramanian et al. show that it contributed to a drop in world trade as a share of world GDP. In other words, a lot of the deglobalization that we’ve seen since 2008 was just China decoupling from countries like Japan and Korea and Taiwan that it used to depend on for high-value components.

In other words, we’ve already seen one big instance of decoupling, and we basically know what it looks like. Today, Indian and Vietnamese and Mexican companies are taking some of the low-value assembly work from China and re-exporting the finished products to America, just like China took that same assembly work from Japan and Korea and Taiwan a generation ago.

But in the future, this low-value assembly role will not satisfy Indian and Vietnamese and Mexican companies. It will not satisfy the Indian and Vietnamese and Mexican governments. And it will not satisfy the Western companies like Apple who will want to get some of their supply chains out of China. India, Vietnam, Mexico, etc. will try to do to China exactly what China did to Japan and Korea after 2008 — move up the value chain and onshore component manufacturing.

If they succeed, then we’ll more of the kind of value-added trade decoupling that Robin Brooks and the writers at The Economist are looking for. And why should they not succeed? Perhaps the doubters believe that Chinese institutions and human capital are just so much better than those in India, Vietnam, Mexico, etc. — even when those countries are assisted by Western multinationals — that those countries will never be able to do what China did, and will be forever stuck doing simple low-value assembly work. But I do not believe that. I believe that just as China learned how to make components, India and Vietnam and Mexico can learn.

But that takes time. China took decades to decouple from Japan, Korea, and Taiwan; other countries will similarly take decades to decouple from China. It’s not the kind of thing that you can expect to happen in just one year, or just five years. And if you look at the situation after one year, or after five years, and say “AHA! India and Vietnam and Mexico haven’t yet accomplished a technological upgrading process that took China thirty years, therefore DECOUPLING IS FAKE!!”, you should probably think more about how this process worked out the last time around.

The Rhodium Group talks quite a bit of sense here:

Firms—foreign and Chinese—are actively diversifying investment and sourcing away from China, in sensitive as well as less sensitive sectors. Because channeling new investments to new markets is easier than finding alternative suppliers, particularly for intermediate inputs, the trend is most visible in the FDI realm.

Because global value chains are so entangled with China, diversification will not necessarily result in a reduced reliance on Chinese inputs and suppliers in the short- to medium-term. A more comprehensive relocation of global supply chains is likely to unfold eventually, especially in sectors like EVs where co-localization is key, but this will happen over an extended period of time.

Because China’s manufacturing clout is so significant, even substantial shifts in production to alternative destinations may only result in small declines in China’s share of global exports, manufacturing or supply chains…

These realities mean that it will take years for advanced economies to achieve the objectives behind their “de-risking” policies—namely limiting trade, investment and supply chain exposure to China in a subset of critical areas. This does not mean that the broader diversification objective is misguided. But policymakers will need to adjust their expectations about the timeframe needed to substantially reduce dependencies. If they do not accept that diversification is a complex, long-term challenge, there is a risk that calls for bolder policy measures to reduce dependencies on China grow. (emphasis mine)

The decoupling-doubters seem to want to jump to the conclusion that diversification has failed. Maybe this is because they had unrealistic expectations of what it would look like, from reading too many economics papers where “decoupling” means instant separation of the world into two disjoint blocs. Or perhaps they see the West’s push for decoupling as a threat to peace and stability in the world, and they want to declare it a failure so we can all go back to the world of 2015. I don’t know.

But either way, rushing to declare decoupling dead simply because India, Vietnam, Mexico, etc. are simply doing in 2023 what China did in 2003 makes no sense. These things are hard, these things take time, but the process is underway.

Update

Mike Bird of The Economist wrote a response to this post on Twitter, and I think it demonstrates some of the basic misunderstandings at work in these articles. Here’s the key tweet:

Bird thinks that what’s happening is relabeling of Chinese finished goods. In other words, he imagines phone being made in China, sold to Vietnam, and then resold to Americans.

In the early days of Trump’s tariffs, there was some of this happening (and Vietnam tried to crack down on it). But right now, this isn’t what’s happening. Instead, China is exporting intermediate goods — components and machines — to Vietnam, which is using them to put together final goods.

Instead of how Bird imagines a new label being slapped on a completed Chinese phone, here’s what you should really be imagining. China sells some screens and chips to a Vietnamese factory, along with some machine tools to assemble these into a phone. The Vietnamese factory combines the Chinese-made components with some others, made in Korea or Japan or Taiwan or the U.S. Vietnamese workers assemble these components into a phone and sell it to the U.S. The Vietnamese value add is relatively low, but it’s far from “minimal”.

That’s basically how supply chains work. Bird imagines that Vietnamese phones are really “made in China” because he’s still mentally operating in a world where production gets done in only one country. A hundred years ago that was largely how it worked, but today, production gets done piecewise, in many countries. A phone sold in America isn’t really “made in China” or “made in Vietnam” — it’s made partly in China and partly in Vietnam and partly in other countries.

And the fact that phone assembly is being done in Vietnam, India, Mexico, and so on really matters a lot. Unlike factories in China, the factories in India or Vietnam will be perfectly happy ordering their components and tools from a variety of countries — South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, Germany, the United States, etc. — which will put a lot more competitive pressure on Chinese suppliers. And over time they will climb up the value chain, producing more components and tools locally, which will extract more and more pieces of the supply chain from China. If you want to read a great post about how this is already happening in India, check out the recent article about Foxconn by Viola Zhou and Nilesh Christopher.

Anyway, this is the crux of the decoupling-doubters’ misunderstanding. They insist on imagining decoupling as an abrupt thunderclap, severing America’s economy from China’s. In fact, it’s more like a slow, messy extraction. But it has clearly begun.

Update 2: Here’s an article in the Nikkei about how Apple is transferring some engineering resources from China to Vietnam. This is exactly how value-chain climbing happens, folks!

I continue to think that the future of world trade is robust, and its shape will surprise us.

By the logic of this piece, one day China will decouple from China. The things that used to be done in China will be outsourced to cheaper venues.

In a similar way, there was a time when the US steel industry led the world, but the US decisively decoupled from its own steel industry, turning to cheaper sources.

Basic idea: Nothing stands still in a capitalist world economy, but the whole almost always grows.

There is an assumption (mostly it seems by US-based commentators) that just because there may indeed be decoupling (even accounting for the 'redwashing' of trade via Mexico, Vietnam etc) between the US and especially China, there is decoupling happening globally. No. Trade is growing and not only between China and the rest of the world but between and amongst multiple other third parties. That the US is being de-emphasised in the pattern of world trade (especially in the non-carbon part of that trade) is not in and of itself concrete evidence of "deglobalization". Perhaps what we are seeing instead is "reorientation", the return of global trade to being centred on Asia?