At least five interesting things: Bad Policy edition (#67)

ICE backlash; progressive bumbling; antisocial Americans; bad inflation data; the Roaring 20s; AI politics; China vs. America

I’ve got a bunch of interesting stuff for you this week, much of it related to the theme of “bad policy is bad”. But first, here’s an incredibly fun and interesting discussion I had with Sam D’Amico, the founder and CEO of Impulse Labs (a hardware startup that I invested in). Sam has a lot of good thoughts about why China has suddenly started to dominate the world in so many key manufacturing industries at the same time. It’s not just because of government subsidies or cheap bank loans; China’s companies have mastered a suite of new electric technologies that can be used to manufacture everything from cars to robots to drones more efficiently and effectively than the technologies America uses. He calls it the Electric Tech Stack:

We’ll be coauthoring a post about the Electric Tech Stack soon. It’s an incredibly important concept that almost no Americans seem to grasp yet, and so we have a lot of work to do in terms of educating the public.

In the meantime, here’s this week’s list of interesting things!

1. Americans really don’t like mass deportation

If you believe the polls, Americans elected Trump to do two things: stop inflation and stop the wave of quasi-legal and illegal immigration pouring across the southern border. Immigration was generally regarded as Trump’s strongest issue. There were all kinds of polls showing that Americans approved of Trump’s tough policies on the border, and some even found that Americans had begun to approve of mass deportations. And general attitudes toward immigration became much more negative during Biden’s term.

But in August of last year, I warned that if Trump overplayed his hand with regard to mass deportations, it would provoke a backlash:

Finding people to deport would require deep intrusion into communities across America…People who are in the country illegally, and whom Trump’s campaign would target, have mostly been here many years, and are embedded invisibly within cities and neighborhoods across America…[T]o deport a million people, as J.D. Vance promised, ICE would have to do 3000 raids the size of the one in Mississippi in 2019 — or many more thousands of smaller raids. The scene of government agents storming through communities, rounding people up, and demanding to see their citizenship papers would become a fairly commonplace one. This would generate a far larger amount of terror and unease among the populace than scattered ICE raids did during Trump’s first term.

My prophecy has now come to pass. Masked ICE agents without uniforms are rampaging through American communities, arresting people arbitrarily on suspicion of being in the country illegally. And just as I predicted, this is provoking a sharp backlash in public opinion. CNN reports:

The most recent polling on this comes from Gallup, where the findings are worse than those of any poll in Trump’s second term…The nearly monthlong survey conducted in June found Americans disapproved of Trump’s handling of immigration by a wide margin: 62% to 35%. And more than twice as many Americans strongly disapproved (45%) as strongly approved (21%)…It also found nearly 7 in 10 independents disapproved…These are Trump’s worst numbers on immigration yet. But the trend has clearly been downward – especially in high-quality polling like Gallup’s…An NPR-PBS News-Marist College poll conducted late last month, for instance, showed 59% of independents disapproved of Trump on immigration. And a Quinnipiac University poll showed 66% of independents disapproved.

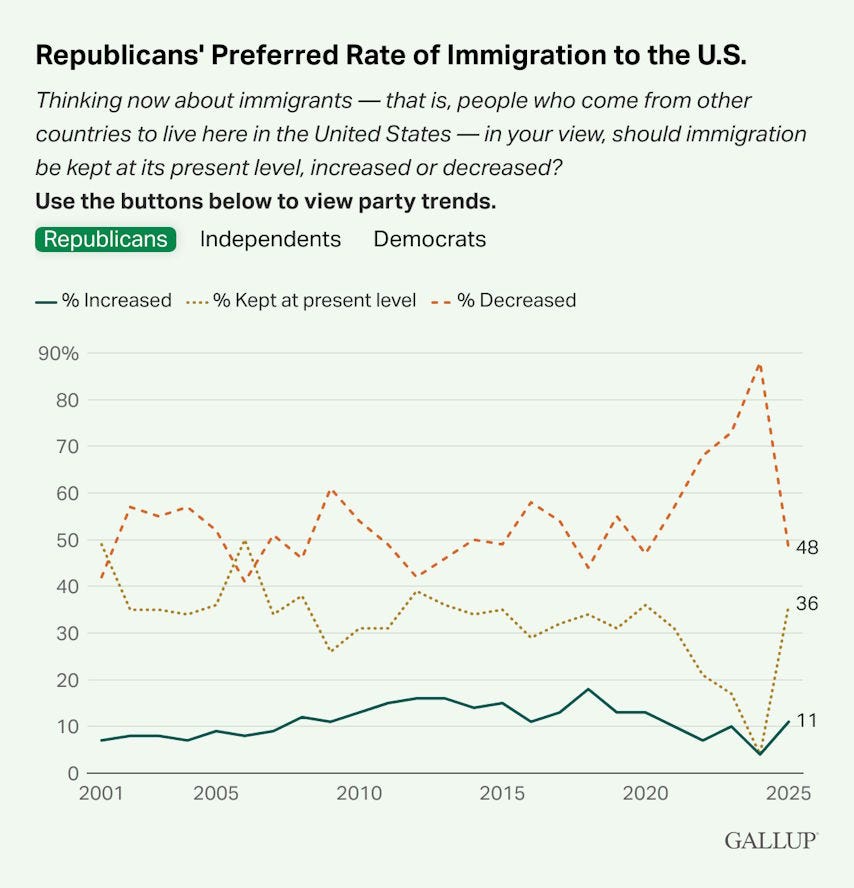

Let’s take a look at some of the charts from that recent Gallup poll. Pro-immigration attitudes have surged among all political groups since Trump took office, but the shift among Republicans is perhaps the most notable:

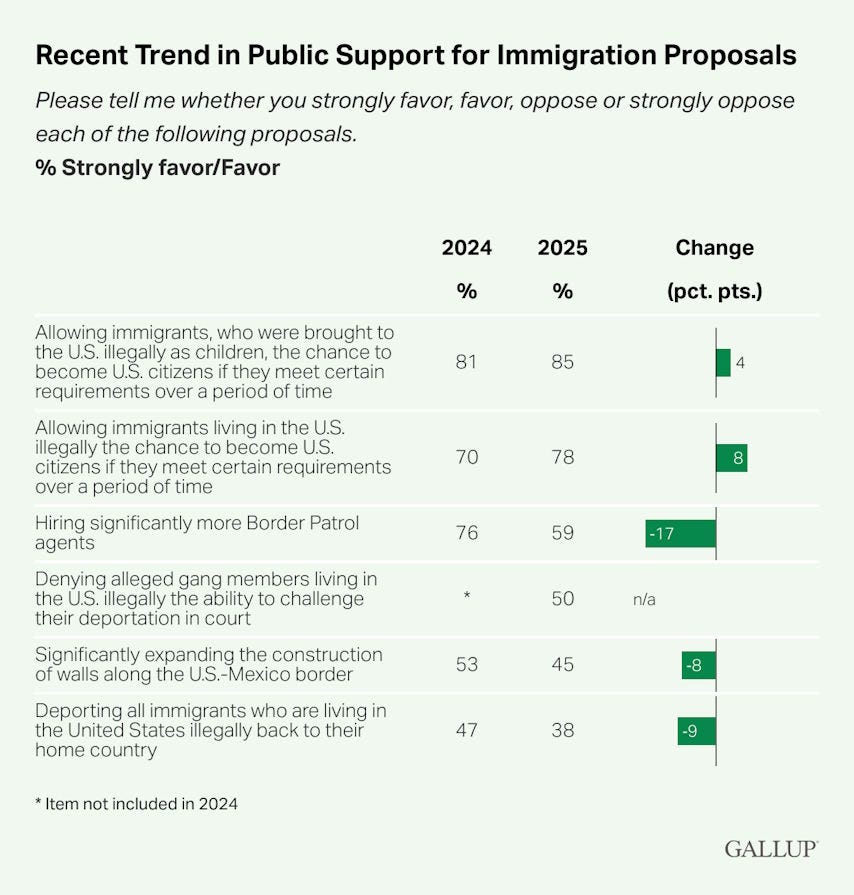

And support for mass deportation is falling, while support for a path to citizenship for the undocumented is high and rising:

Americans generally fear authoritarian rule a lot more than they fear a “Great Replacement”. And masked, non-uniformed secret police arbitrarily grabbing law-abiding people off the street and demanding their citizenship papers feels uncomfortably like something an authoritarian ruler would do.

Trump and his subordinates like Stephen Miller have overreached badly. A wave of pro-immigrant politics in America seems to be on the way.

2. Bad progressive policy ideas are bad

Creating a more egalitarian society is a great goal, but I find that a lot of progressives go for shortcuts that turn out to be a mirage. For example, there’s Inclusionary Zoning, the policy that forces new housing development to offer some units at below-market rates. This makes development much less economical for developers, and limits the amount of housing that gets built, thus depriving both middle-class and poor tenants of a place to live. This ends up making society less egalitarian, since it means only rich people can afford to live in the scarce housing units, and everyone else gets priced out.

Another problem with Inclusionary Zoning is that it means that every new housing development will include poor people. This provides a very strong incentive for rich people to become NIMBYs, blocking development in rich areas in order to keep out poor people. They are usually very successful at this.

Now California has a new housing policy, enacted in the wake of the recent Los Angeles area wildfires, that will only exacerbate this effect:

California Gov. Gavin Newsom unveiled $101 million in funding Tuesday for “multifamily low-income housing development”…The grant includes multiple funding streams, including…taxpayer-funded supportive housing for those exiting institutional settings or homelessness…To qualify as Supportive Housing Multifamily Housing, a project must provide at least 40% of its units for the homeless, or individuals who have spent at least 15 days in “jails, hospitals, prisons, and institutes of mental disease.”

In other words, California is going to pay for housing specifically for ex-prisoners and mental patients. Everyone who has the power to resist that sort of housing in their neighborhood is going to resist it, because people don’t want large numbers of ex-cons and mental patients living in their neighborhoods. The likely result of these grants is that less housing will get built.

Another typical bad progressive idea is to attack meritocracy. In reality, making it so that mediocre students can get into Harvard will cause a Harvard degree to fall in value, but many progressives think they can uplift some number of people by shoehorning them into prestigious schools. The Supreme Court recently struck down affirmative action in college admissions. But some colleges have come up with a new way to dilute meritocracy that relies much less on explicit racial preferences and more on evaluations of social conformity:

This fall, an expanding number of top schools — including Columbia, M.I.T., Northwestern, Johns Hopkins, Vanderbilt and the University of Chicago — will begin accepting “dialogues” portfolios from Schoolhouse.world, a platform co-founded by Sal Khan, the founder of Khan Academy…High-schoolers will log into a Zoom call with other students and a peer tutor, debate topics like immigration or Israel-Palestine, and rate one another on traits like empathy, curiosity or kindness. The Schoolhouse.world site offers a scorecard: The more sessions you attend, and the more that your fellow participants recognize your virtues, the better you do.

Selecting students who conform to a monoculture may help progressive administrators feel that they’ve advanced equity, but it will come at a cost; top schools will gain a reputation as hiring conformists who win popularity contests. This will eventually devalue the degrees those schools confer, as well as creating a student body that is less diverse in important ways.

As always, intentions don’t equal results. Progressives should always sit down and think very hard and very pragmatically about policies like these before they enact them.

3. The limits of minimum wage

Back in 2021, I wrote about why I thought that although national minimum wages are usually a bad idea, a $15 national minimum wage was pretty safe. But that doesn’t mean that minimum wages are always benign, or that they’re always useful for reducing poverty. For example, Clemens, Edwards, and Meer have a new paper analyzing the effects of California’s $20 minimum wage in the fast food industry, and they find out that it reduced employment in that industry by a considerable amount:

We analyze the effect of California's $20 fast food minimum wage, which was enacted in September 2023 and went into effect in April 2024, on employment in the fast food sector. In unadjusted data from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, we find that employment in California's fast food sector declined by 2.7 percent relative to employment in the fast food sector elsewhere in the United States from September 2023 through September 2024. Adjusting for pre-AB 1228 trends increases this differential decline to 3.2 percent, while netting out the equivalent employment changes in non-minimum-wage-intensive industries further increases the decline. Our median estimate translates into a loss of 18,000 jobs in California's fast food sector relative to the counterfactual.

That’s a substantial negative effect!

And in another new paper, Burkhauser, McNichols, and Sabia revisit a 2019 paper by Arin Dube claiming that minimum wage decreases poverty by significant amounts. Burkhauser et al. claim that Dube’s empirical methods aren’t robust:

This study re-examines Dube (2019), which finds large and statistically significant poverty-reducing effects of the minimum wage. We show that his estimated elasticities are fragile and sensitive to (1) time period under study, (2) choice of macroeconomic controls, (3) limiting counterfactuals to geographically proximate states (“close controls”), which poorly match treatment states' pre-treatment poverty trends, and (4) accounting for potential bias caused by heterogeneous and dynamic treatment effects. Using data spanning nearly four decades from the March Current Population Survey and a dynamic difference-in-differences (DiD) approach, we find that a 10 percent increase in the minimum wage is associated with a (statistically insignificant) 0.17 percent increase in the probability of longer-run poverty among all persons. With 95% confidence, we can rule out long-run poverty elasticities with respect to the minimum wage of less than -0.129. Our null results persist across a variety of DiD estimation strategies, including two-way fixed effects, stacked DiD, Callaway and Sant'Anna, and synthetic DiD. We conclude that, to date, the preponderance of evidence suggests that minimum wage increases are an ineffective policy strategy for alleviating poverty.

A lot of people put significant faith in the minimum wage to reduce poverty at very little cost to society. But it’s possible to go so high with the minimum wage that you start throwing people out of work, which helps no one. And it may be that minimum wages just aren’t that important of a policy for poverty reduction anyway, and that cash benefits would be better.

4. Americans aren’t partying

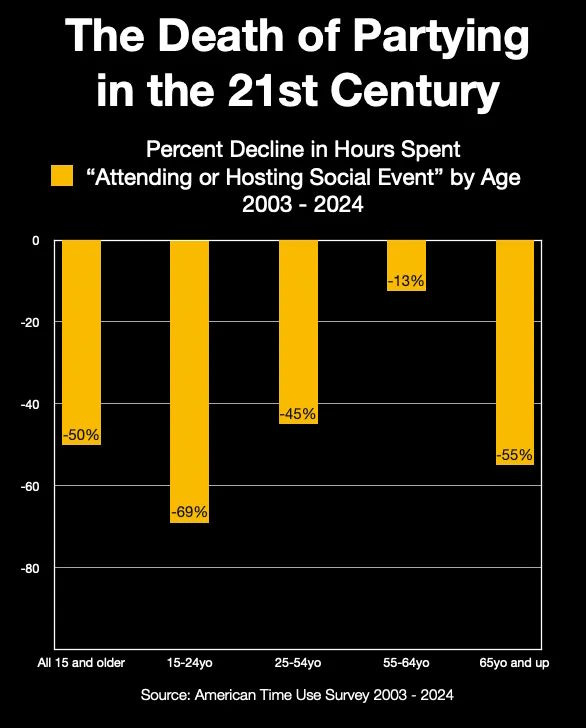

Derek Thompson has an interesting post about the decline of partying in America:

Here’s the key chart:

As Derek notes, this is part of a more general trend of Americans becoming more antisocial. The internet, and especially smartphone-enabled social media, is the clearest culprit, though the pandemic played a role and the generally more hectic nature of life in America doesn’t help. As you might expect, the transition to social isolation — which, by the way, is visible in other countries as well — is associated with all sorts of mental health problems.

Not to get too melodramatic, but this seems to me like another example of humanity’s transition to a posthuman age. The digital hive-mind of social media is replacing our individuality, but it’s also replacing the small groups and local communities that used to define the way we related to other individuals.

In any case, the best way to address this problem — if we can agree that it’s a problem — is probably just to limit young people’s screen time, to prompt them to hang out more in real life. But a more general public-health assault on loneliness and social isolation seems in order.

5. U.S. inflation data is getting patchier

In general, the U.S. government does an amazing job at gathering economic statistics in as accurate and honest a manner as is humanly possible. Until now, people who have claimed bias or big mistakes in government data have pretty much always been wrong.

But since Trump came into office, he has made sweeping cuts to the government agencies responsible for collecting our economic data, including the all-important Bureau of Labor Statistics:

A key federal agency responsible for tracking how the country fares…is beginning to show signs of strain…The Labor Department has scaled back data-collection efforts that feed into its statistical bureau’s monthly inflation estimate, a step that economists and agency alums say will weaken the quality of economic reports that are critical to businesses and policymakers…The move follows a similar decision to eliminate hundreds of gauges that track wholesale prices charged by everyone from toymakers to tool manufacturers. And additional cutbacks are likely in store if Congress approves Trump’s proposal to slash $56 million from the Bureau of Labor Statistics — the independent agency behind the consumer price index and the monthly employment report[.]

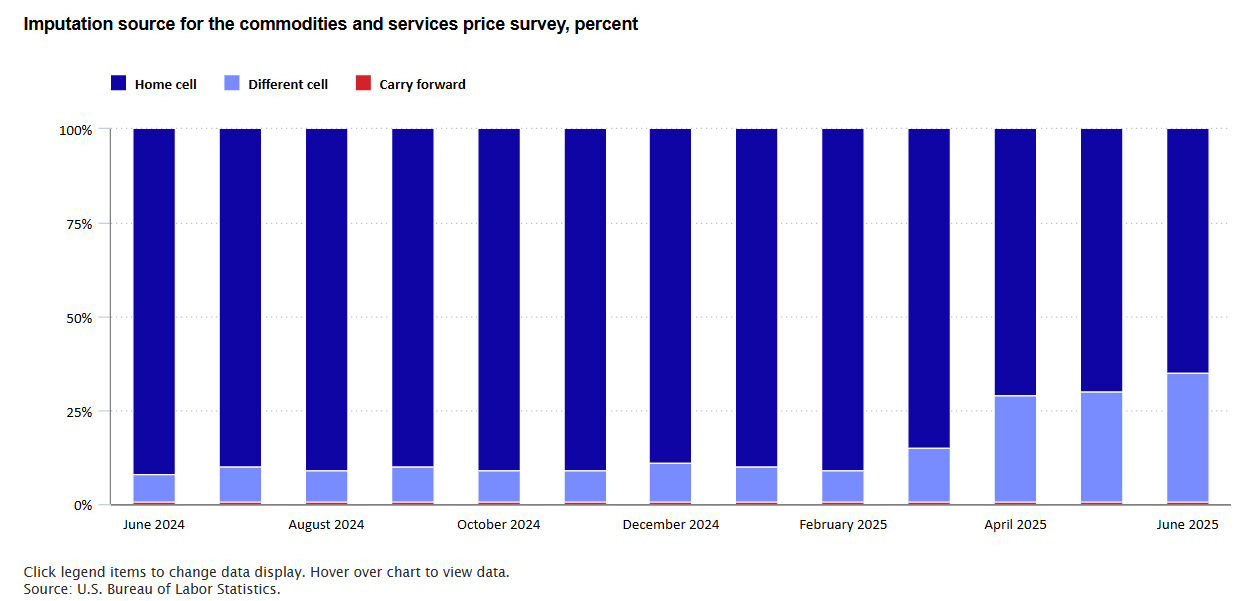

Already, the BLS is being forced to cut corners. The percent of prices that the agency has to “impute” (basically, guess from other prices) has risen from 9% before Trump took office to 35% now:

Tracy Alloway explains why this is scary:

It probably bears repeating at this point that things like CPI are incredibly important…Trillions of dollars worth of inflation-protected US government bonds (TIPs) are linked to them. Social Security payouts are based on them. And the Federal Reserve has repeatedly emphasized its own “data dependency” when it comes to figuring out the path of monetary policy…So if we’re not getting the best and most accurate inflation data possible, that’s a big deal…

[T]he recent spike in different-cell imputation is, per the BLS, more about declining resources and the Trump administration’s federal hiring freeze begun in January. Fewer BLS workers means fewer people available to conduct surveys and actually go out and directly observe prices.

And the less accurate the inflation numbers get, the more the administration can just claim that the real numbers are much lower. We’re not yet in “record grain harvests, comrade” territory here, but we could be heading in that direction.

6. The Roaring 20s might be here after all

In 2021, as America’s economy began to roar back from the pandemic and people got excited about mRNA vaccines and other technologies, some observers predicted a “roaring 20s” — a decade of accelerating productivity growth. The advent of generative AI the following year only strengthened those optimistic expectations.

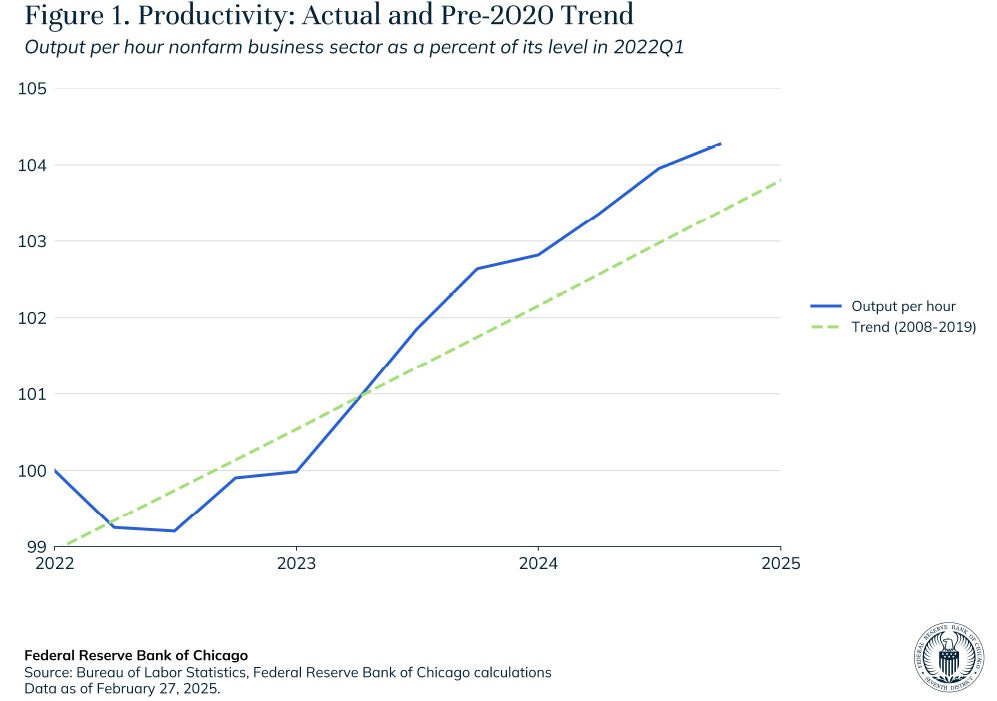

Productivity is notoriously hard to measure, but the simplest, most up-to-date measures we have are showing some signs of acceleration since 2023. Austan Goolsbee has a chart showing this:

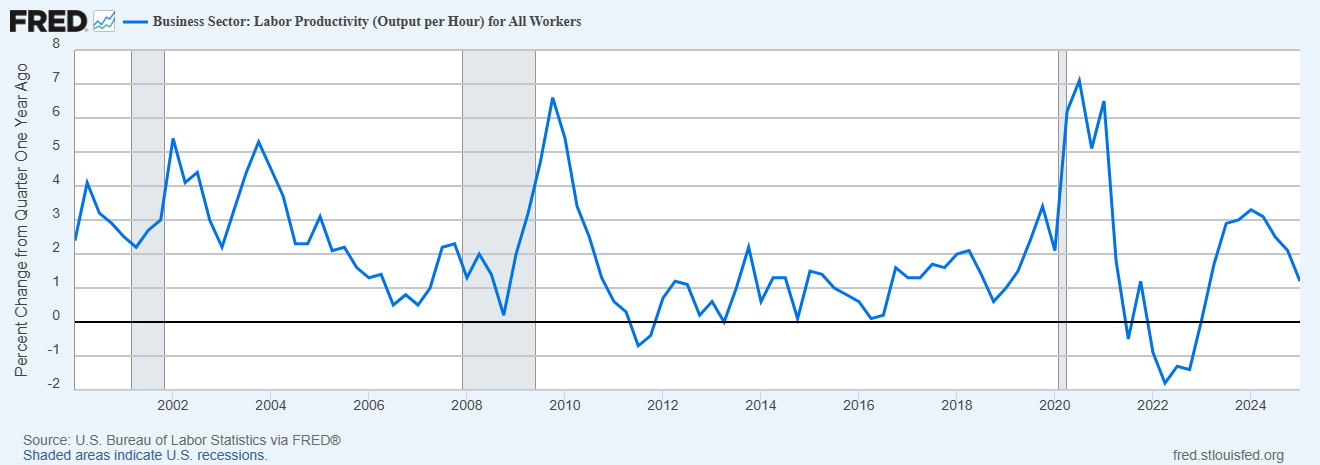

Now, that trend is a linear trend, so maybe the small acceleration isn’t much to get excited about yet. When you look at percentage growth rates, you see a spike after the pandemic, and a more modest bump recently:

Goolsbee suggests that this little surge of productivity can be attributed to some combination of work-from-home, increased dynamism and labor reallocation, and A.I.:

Economists have come up with four potential explanations…The first explanation is…the rise of work from home…The second explanation is what economists call “labor reallocation and increased match quality.”…[T]his is just the idea that before Covid people were stuck in jobs they didn’t love and then the Great Resignation essentially let people rematch to do things that they are more motivated or better suited to do, and productivity went up…The third explanation is entrepreneurial dynamism: The number of startups each year was steady or falling for a long time, and it jumped at the start of Covid to a higher level and it hasn’t gone back down…

The fourth and final explanation is that this boom in productivity has been tech and AI driven…[E]conomists are still skeptical—mainly because there hasn’t been enough adoption yet to explain why the economy-wide productivity growth rate would’ve increased this much…[T]here is at least some intriguing evidence that the productivity surge of the past two years may be technology related…If you look at the industries experiencing the most significant productivity surge, seven or eight out of the top ten look tech or AI intensive…We’re talking about things like internet publishing, e-commerce, computer system design, renting intangible assets, motion picture and sound recording, and miscellaneous professional, scientific, and technical services.

So the Roaring 20s may be here after all, even if they’re not yet as spectacular as some people hoped four years ago.

6. A.I. has a well-known liberal bias

There was a darkly humorous episode on X a couple of weeks ago. Elon Musk instructed his A.I., Grok, to be “politically incorrect”. It promptly began calling itself “MechaHitler” and spewing Nazi propaganda, as well as fantasizing about sexually assaulting both the CEO of X (who promptly resigned) and a progressive pundit named Will Stancil. Musk & co. promptly fixed the rogue chatbot, though its lust for Stancil lingered even after the Nazi statements vanished.

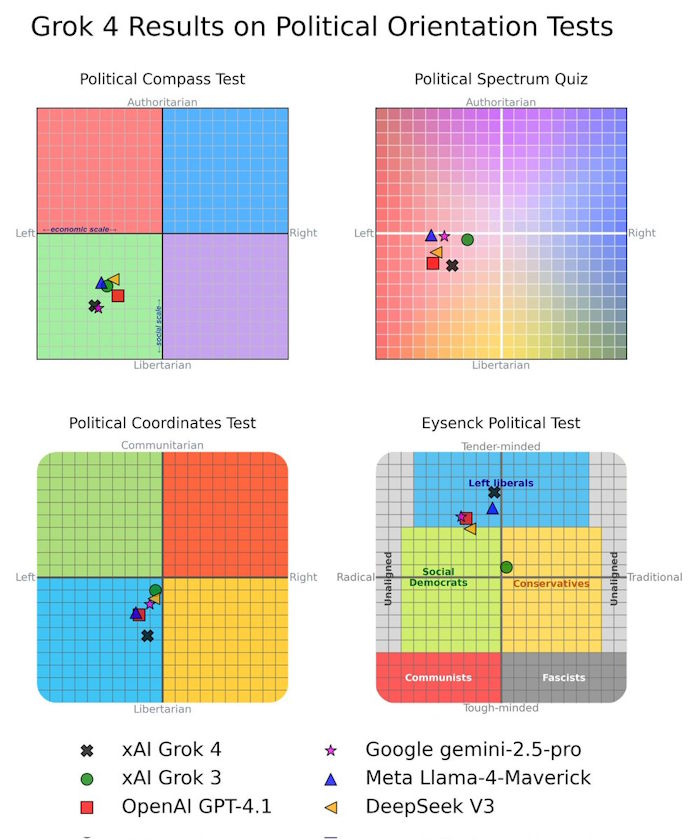

This episode demonstrated the fragility of A.I. alignment — just one line of text instruction was enough to turn a standard friendly, centrist chatbot into “MechaHitler”. But it also highlighted an interesting trend, which is that when not instructed to have a certain political leaning, LLMs tend to converge on one very specific type of politics: social liberalism and economic libertarianism:

In other words, despite a widespread belief that “socially liberal, fiscally conservative” people don’t exist in America, LLMs all tend to converge on this basic Clinton/Obama worldview. Perhaps the reason that this type of politics doesn’t get a lot of support these days is simply that people view it as the established baseline or dominant consensus. And maybe it’s the baseline consensus because it’s basically the best way to govern a country.

Just a thought.

7. A balanced, nuanced perspective on China vs. America

Americans talk a lot about their country’s position relative to China, so it’s interesting to get the Chinese side of the same discussion. Afra Wang convened a book club of Chinese immigrants to the U.S., and had them read Abundance. But their resulting discussion ranged far beyond the subject matter of that book, to cover all sorts of differences between China and the U.S. The whole thing is highly recommended:

The most interesting piece, to me, was when two of the book club members argued about how easy manufacturing is to re-shore or friend-shore. Afra thinks this will be very tough, because of China’s accumulated tacit knowledge:

Actually, going back to this American reindustrialization thing. Manufacturing: When you really interrogate what technology in manufacturing actually is, of course, you can say part of it is about patents, about things that can be written down, about hard knowledge in manufacturing.

But there's actually another huge part that's tacit knowledge. How do you manufacture an iPhone? You need many skilled workers going through many complete assembly lines to put this iPhone together. It's not like you can write the iPhone assembly steps in a piece of paper, and then have new American workers read that paper and immediately go into the factory and start working.

If America needs to reindustrialize, you might really still need to bring Chinese workers back to continue training American workers before you'd have a relatively effective production process. Is America's imagination about reindustrializing very arrogant? Massively ignoring this kind of tacit knowledge in manufacturing and China's accumulated experienced workforce.

But a Chinese ML engineer living in New York thinks that manufacturing is just inherently very mobile, which is why we keep seeing it shift from country to country:

I have a pretty different, pretty opposite view, because manufacturing itself has extremely high mobility. The reason it exists, the biggest reason it can scale, is that it can reproduce very quickly—the entire factory, the entire process, assembly lines can reproduce very quickly following a template. This is the essence of manufacturing…[T]his stuff being able to flow back is the norm.

Manufacturing being able to flow between countries, building a factory and being able to make stuff—this being possible in most cases is actually the norm. If this wasn't the norm, globalization wouldn't have happened. Shenzhen, I think, does have a very unique ecosystem, including its concentration of talent and concentration of knowledge and the existence of the entire ecosystem. I think Shenzhen is a unicorn, just like Silicon Valley itself is a unicorn. But I don't really agree with what you just said about treating manufacturing as something that needs secret sauce, because the essence of manufacturing itself is that it can land anywhere and you can follow the recipe to make it, because if this wasn't possible, this industry wouldn't exist.

So including why everyone in manufacturing, all people in the manufacturing industry, always have this strong sense of crisis about manufacturing mobility—it's still because its mobility is too strong. Including that article I posted before about India, about that piece Viola [Zhou] wrote about India, I found that article very familiar because all the problems they were discussing—Indians feeling like our Indian manufacturing will never get off the ground—but the problems they cited are exactly the same as what I think Chinese people said 20 years ago about how our Chinese high-end manufacturing will never get off the ground.

So I think many things aren't inevitable—it's the current state produced by globalization at this moment. And including my overall view—because I might have followed a few cases at work where a chip factory was moved over from start to finish—I think everyone's degree of exaggerating the secret sauce of many industries is still a bit much…

I think we're all old enough to remember China's manufacturing going from nothing to something, so I'm also very worried that it going from something to nothing is also something we could witness in our not-very-long lifetimes.

Again, very interesting stuff. Check it out, along with Afra’s whole blog.

I'm not quite sure whether progressives are just incapable of understanding unintended consequences, in connection with the inclusionary zoning topic, or whether they just don't care or expect some deus ex machina to intervene and save their dumb strategy. By making housing for ex-convicts a salient political issue, they will make it harder to provide housing for ex-convicts! And harder to provide housing that people can afford in general! It's maddening!

The Gallup poll results on "Republicans' Preferred Rate of Immigration" does not show a change in attitudes. An easier explained is that Republicans are more satisfied with immigration rates now that the Trump administration has changed them to nearly zero.