The dawn of the posthuman age

Between new technology and low fertility, our existence as a species is not going to be the same.

“Can you picture what we’ll be/ So limitless and free/ Desperately in need of some stranger’s hand” — The Doors

In the 1990s and 2000s, a lot of science fiction focused on what Vernor Vinge called “the Singularity” — an acceleration of technological progress so dramatic that it would leave human existence utterly transformed in ways that it would be impossible to predict in advance. Vinge believed that the Singularity would result from rapidly self-improving AI, while Ray Kurzweil associated it with personality upload. But both believed that something big was on the way.

In the late 2000s and 2010s, as productivity growth slowed down, these wild expectations got tempered a bit. Cory Doctorow and Charles Stross poked fun at the idea of the Singularity as “the rapture of the nerds”. And some bloggers, like Brad DeLong and Cosma Shalizi, began to argue that the true Singularity was in the past, when the Industrial Revolution freed us from the constraints of daily hunger and scarcity. Here’s Shalizi:

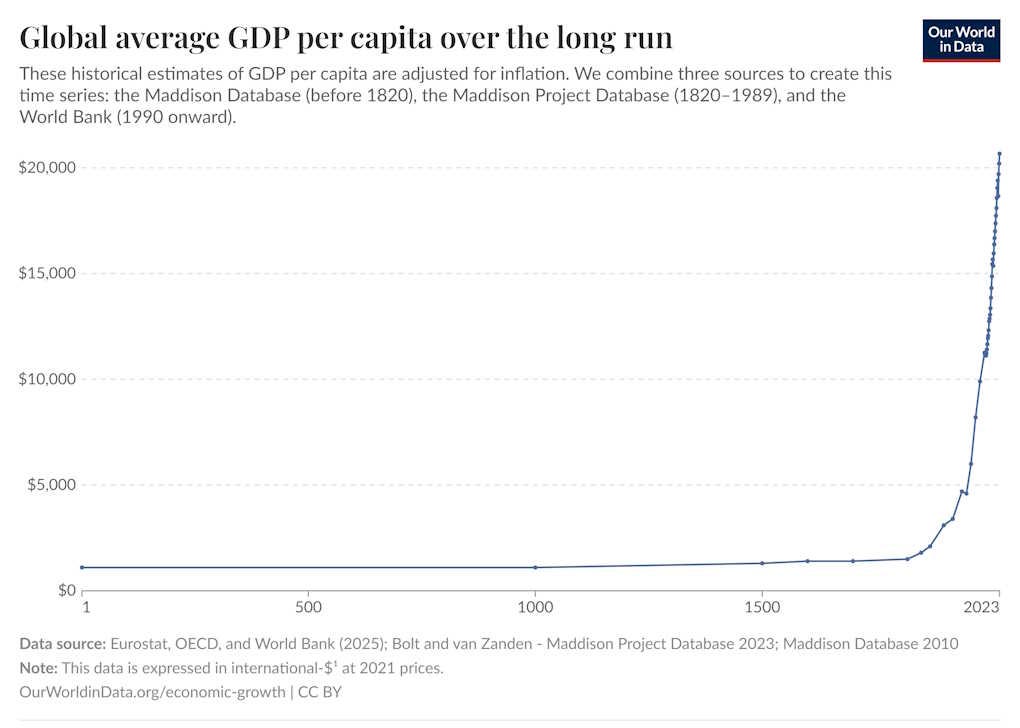

The Singularity has happened; we call it "the industrial revolution" or "the long nineteenth century". It was over by the close of 1918…Exponential yet basically unpredictable growth of technology, rendering long-term extrapolation impossible (even when attempted by geniuses)? Check…Massive, profoundly dis-orienting transformation in the life of humanity, extending to our ecology, mentality and social organization? Check…Embrace of the fusion of humanity and machines? Check…Creation of vast, inhuman distributed systems of information-processing, communication and control, "the coldest of all cold monsters"? Check; we call them "the self-regulating market system" and "modern bureaucracies" (public or private), and they treat men and women, even those whose minds and bodies instantiate them, like straw dogs…An implacable drive on the part of those networks to expand, to entrain more and more of the world within their own sphere? Check…

Why, then, since the Singularity is so plainly, even intrusively, visible in our past, does science fiction persist in placing a pale mirage of it in our future? Perhaps: the owl of Minerva flies at dusk; and we are in the late afternoon, fitfully dreaming of the half-glimpsed events of the day, waiting for the stars to come out.

I agree that the Industrial Revolution represented an abrupt, unprecedented, and utterly transformational change in the nature of human life. Human life until the late 1800s had been defined by a constant desperate struggle against material poverty, with even the bounty of the agricultural age running up against Malthusian constraints. Suddenly, in just a few decades, humans in developed countries were fed, clothed, and housed, and had leisure time to discover who they really wanted to be. It was by far the most important thing that had ever happened to our species:

And it’s important to note that this transformation wasn’t just a result of technology giving humans more stuff. It depended crucially on reductions in human fertility. As Brad DeLong documents in his excellent book Slouching Towards Utopia, after a few decades, the Industrial Revolution prompted humans to start having fewer children, which prevented the bounty of industrial technology from eventually being dissipated by the old Malthusian constraints.

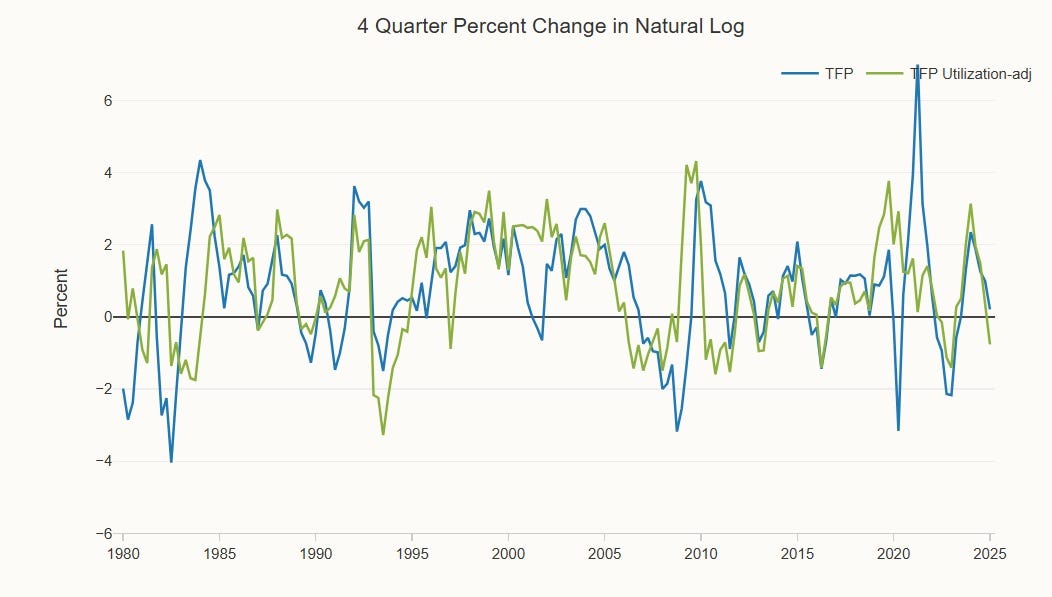

Since the productivity slowdown of the mid-2000s, it has become fashionable to say that the Singularity of the Industrial Revolution is over, and that humanity has reached a plateau in living standards. Although some people expect generative AI to re-accelerate growth, we haven’t yet seen any sign of such a mega-boom in either the total factor productivity numbers or the labor productivity numbers:

Of course, it’s still early days; AI may yet produce the vast material bounty that optimists expect. And yet even if it never does, I don’t think that means humanity is in for an era of stagnation. The Industrial Revolution was only transformative because it changed the experience of human life; a GDP line on a chart is only important because it’s correlated with so many of the things that matter for human beings.

And so if new technologies and social changes fundamentally alter what it means to be human, I think their impact could be as important as the Industrial Revolution itself — or at least, in the same general ballpark. In a post back in 2022 and another in 2023, I listed a bunch of ways that the internet has already changed the experience of human life from when I was a kid, despite only modest productivity gains. Looking forward, I can see even bigger changes already in the works.

In key ways, it feels like we’re entering a posthuman age.

The Second Fertility Transition and the winnowing of the human race

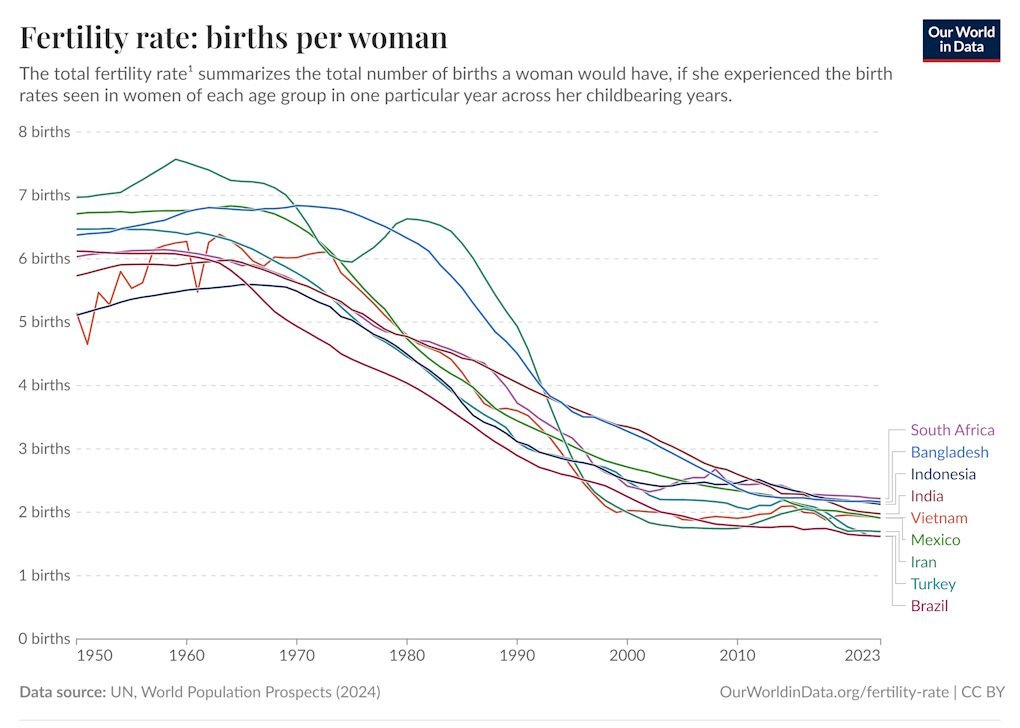

When countries get richer, more urbanized, and more educated, their birth rates fall by a lot — this is known as the “fertility transition”. Typically, this means that the total fertility rate goes from around 5 to 7 to around 1.4 to 2. This is mostly a result of couples choosing to have fewer children. Here’s a chart where you can see the fertility transition for a bunch of large developing countries in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East:

2 children per woman1 is around the level where population is stable in the long term — actually, it’s about 2.1 for a rich country and 2.3 for a poor country, to take into account the fact that some kids don’t survive until adulthood. But basically, going from 5-7 kids per woman to 2 means that your population goes from “exploding” to “stable”.

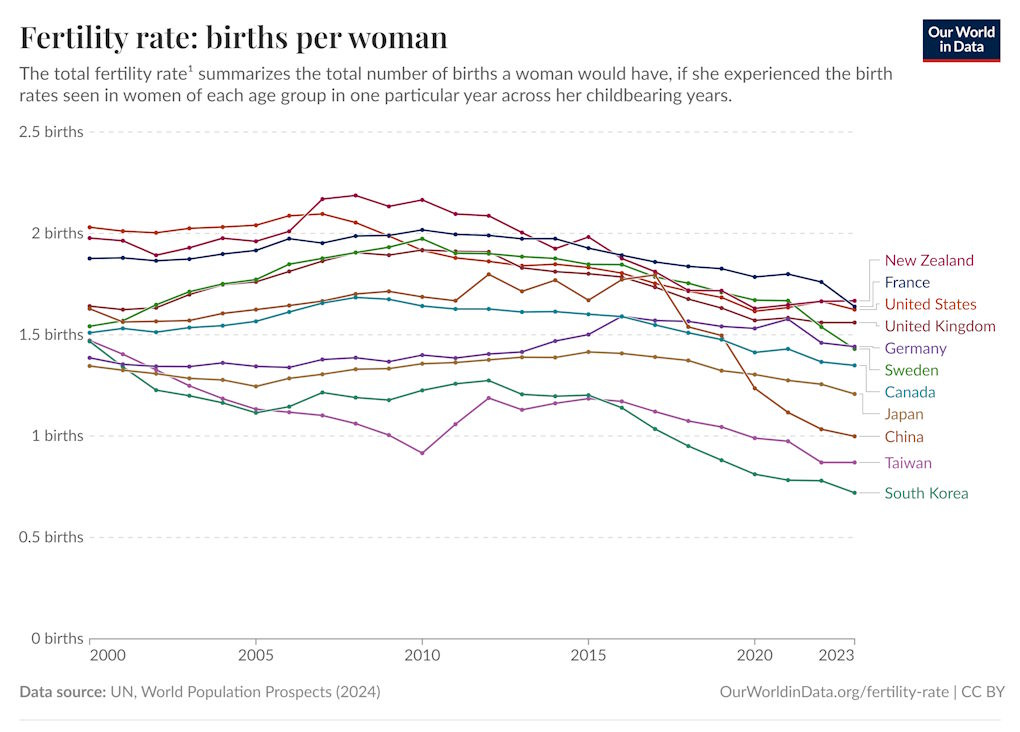

For some rich countries like Japan, fertility fell to an especially low level, of around 1.3 or 1.4. This implied long-term population shrinkage — Japan’s population began shrinking in the 2000s — and an increasing old-age dependency burden. But as long as this low level of fertility was confined to a few countries, it didn’t feel like an emergency — a few rich nations like America, New Zealand, France, and Sweden still managed to have fertility rates that were at or near replacement. For everyone else, there was always immigration.

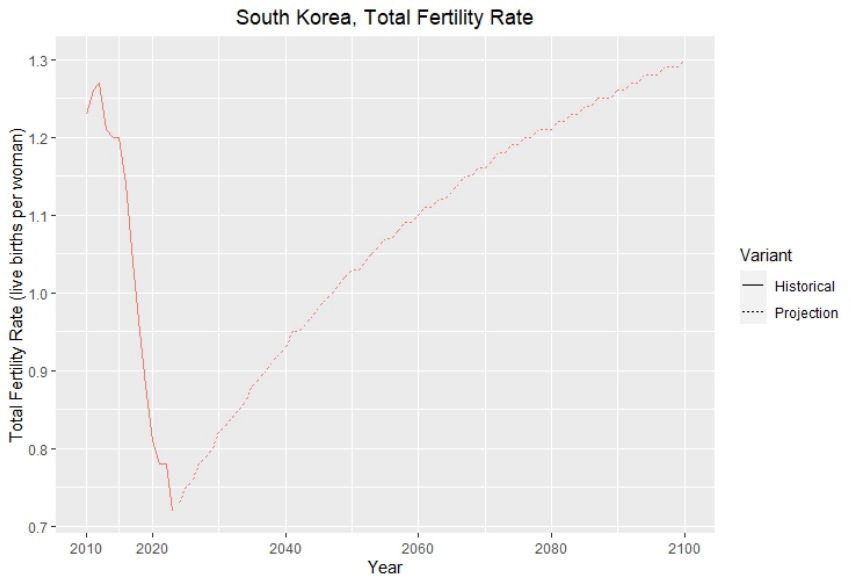

That’s where the dialogue on fertility stood in 2015. But over the past decade, there has been a second fertility transition in rich countries, from low levels to very low levels. Even countries like the U.S., France, New Zealand, and Sweden have now switched to rates well below replacement, while countries like China, Taiwan, and South Korea are at levels that imply catastrophic population collapses over the next century:

Meanwhile, the rate of fertility decline in poor countries has accelerated. The UN calls the drop “unprecedented”.

The economist Jesus Fernandez-Villaverde believes that things are even worse than they appear. Here are his slides from a recent talk he gave called “The Demographic Future of Humanity: Facts and Consequences”. And here’s a YouTube video of him giving the talk:

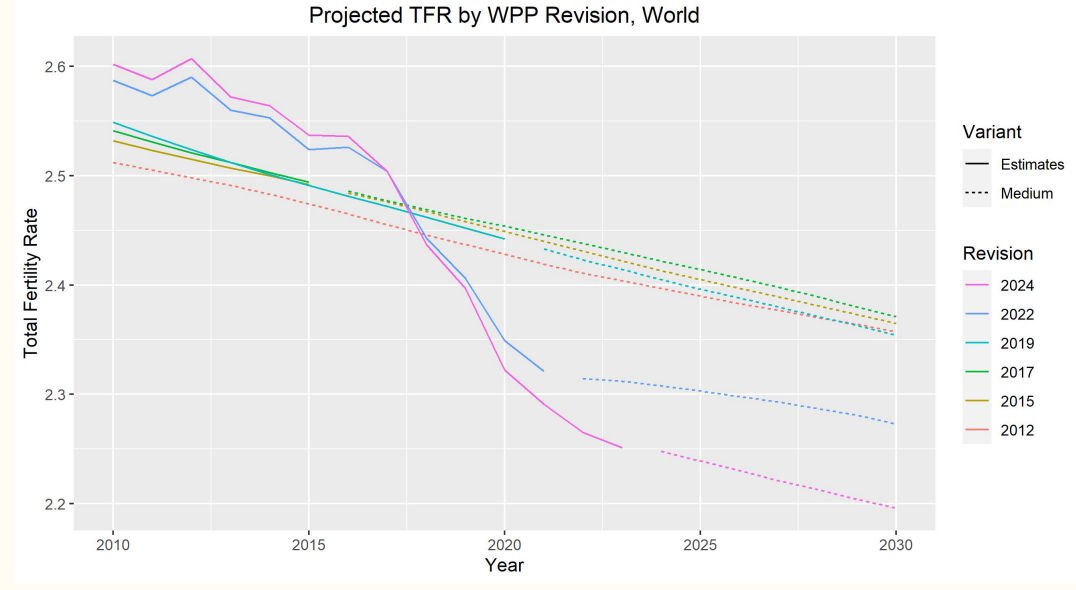

Fernandez-Villaverde notes that the statistical agencies tasked with estimating current global fertility and making future projections have consistently revised their numbers down and down:

This doesn’t just mean people are having fewer kids; it means that because of past errors in estimating how many kids people had, there are now fewer people to have kids than we thought. Fernandez-Villaverde shows that this is true across nearly all developing countries. As a result of these mistakes, Fernandez-Villaverde thinks the world is already at replacement-level fertility.

Furthermore, population projections are based on assumptions that fertility will bounce sharply back from its current lows, instead of continuing to fall. Those predictions look a little bit ridiculous when you show them on a graph:

As a result, Fernandez-Villaverde thinks total global population is going to peak just 30 years from now.

This is a big problem. The first fertility transition was a good thing — it was the result of the world getting richer, it saved human living standards from hitting a Malthusian ceiling, and it seemed like with wise policies, rich countries could keep their fertility near replacement rates. But this second fertility transition is going to be an economic catastrophe if it continues.

The difference between a fertility rate of 1 and a rate of 2 might seem a lot smaller than the difference between 2 and 6. But because of the math of exponential curves, it’s actually just as important of a change. Going from 6 to 2 means your population goes from exploding to stable; going from 2 to 1 means your population goes from stable to vanishing.

This is going to cause a lot of economic problems. I wrote about these back in 2023:

Shrinking populations are continuously aging populations, meaning that each young working person has to support more and more retirees every year. On top of that, population aging appears to slow down productivity growth through various mechanisms. Immigration can help a bit, but it can’t really solve this problem, since A) when the whole world has low fertility there is no longer a source of young immigrants, and B) immigration is bad at improving dependency ratios because immigrants are already partway to retirement.

And in the long run, shrinking populations could slow down productivity growth even more, by shrinking the number of researchers and inventors; this is the thesis of Charles Jones’ 2022 paper “The End of Economic Growth? Unintended Consequences of a Declining Population”. Unless AI manages to fully replace human scientists and engineers, a shrinking population means that our supply of new ideas will inevitably dwindle.2 Between this effect and the well-documented productivity drag from aging, the idea that we’ll be able to sustain economic growth through automation seems dubious.

What’s going on? Unlike the first fertility transition, this second one appears driven by increasing childlessness — people never forming couples or having kids at all, instead of simply having fewer kids. And although it’s not clear why that’s happening, the obvious culprit is technology itself — mobile phones and social media. This is Alice Evans’ hypothesis, and there’s some evidence to suggest she’s right. In China, “new media” (i.e. social media) use was found to be correlated with low desire to have children. The same correlation has been found in Africa.

Of course better research is needed, particularly natural experiments that look at the response to some exogenous factor that increases social media use. But the timing and the worldwide nature of the decline — basically, every region of the globe started getting sharply lower fertility starting in the mid to late 2010s — makes it difficult to imagine any other cause. And the general mechanism — internet use substituting for offline family relationships — is obvious.

Economic stagnation isn’t the only way the Second Fertility Transition will change our society. The measures we take to try to sustain our population will leave their mark as well. Last November, I looked at the history of pronatal policies, and concluded that things like paying people to have more kids, or making it easier to have kids, or encouraging cultural changes are unlikely to work:

Unfortunately, that’s likely to lead to more coercive solutions. In my post, I predicted that countries would try to cut childless people off from old-age pensions and medical benefits:

In the past, when fertility rates were high, children served an economic purpose — they were farm labor, and they were also people’s old-age pension. If parents lived past the point where they were physically able to work, their children were expected to support them. In order to make sure you had at least a few kids who survived long enough to support you, you had to have a large family.

Denying old-age benefits to the childless would be an obvious way to try to reproduce this premodern pattern. This would, of course, result in horrific widespread old-age poverty for those who didn’t comply…I predict that some authoritarian states — China, perhaps, or Russia, or North Korea — will eventually turn to ideas like this if no one ever finds a way to raise fertility voluntarily.

This idea actually comes from a 2005 paper by Boldrin et al., who find that if you model fertility decisions as an economic calculation, then Social Security and other old-age transfers are responsible for much of the fertility decline in rich nations:

In the Boldrin and Jones' framework parents procreate because the children care about their old parents' utility, and thus provide them with old age transfers…The effect of increases in government provided pensions on fertility…in the Boldrin and Jones model is sizeable and accounts for between 55 and 65% of the observed Europe-US fertility differences both across countries and across time and over 80% of the observed variation seen in a broad cross-section of countries.

Ending old-age benefits for the childless would be a pretty dystopian policy. But in the long run, extreme population aging, coupled with slower productivity growth, will make it economically impossible for young people to support old people no matter what policies government enact.3

And if desperate, last-ditch draconian measures fail, we will shrink and dwindle as a species. The vitality and energy of young people will slowly vanish from the physical world, as the youth become tiny islands within a sea of the graying and old. Already I can feel this when I go to Japan; neighborhoods like Shibuya in Tokyo or Shinsaibashi in Osaka that felt bustling and alive with young people in the 2000s are now dominated by middle-aged and elderly people and tourists.

And as population itself shrinks, the built environment will become more and more empty; whole towns will vanish from the map, as humanity huddles together in a dwindling number of graying megacities. Our impact on the planet’s environment will finally be reduced — we will still send out legions of robots to cultivate food and mine minerals, but as our numbers decrease, our desire to cannibalize the planet will hit its limits.

But even as humanity shrinks in physical space, we will bind ourselves more tightly together in digital space.

From industrial individual to digital collective

When I was a child, sometimes I felt bored; now I never do. Sometimes I felt lonely; now, if I ever do, it’s not for lack of company. Social media has wiped away those experiences, by putting me in constant contact with the whole vast sea of humanity. I can watch people on YouTube or TikTok, talk to my friends in chat groups or video calls, and argue with strangers on X and Substack. I am constantly swimming in a sea of digitized human presences. We all are.

Humanity was never fully an individual organism. Our families and communities were always collectives, as were the hierarchies of companies and armies and even the imagined communities of nation-states. But the internet has made the collective far larger than it was. In many ways it’s also more connected; one survey found that the average American spends 6 hours and 40 minutes, or more than a third of their waking life, online. About 30% of Americans say they’re online almost constantly.

The results of this constant global connectedness are far too deep and complex to deal with in one blog post. But one important result is to replace some fraction of individual human effort with the preexisting effort of the collective.

Instead of figuring out how to fix our own houses, build our own furniture, or install our own appliances, a human in 2021 could watch YouTube videos. Instead of figuring out how to write a difficult piece of code, a programmer could ask the Stack Exchange forum. Instead of creating a new funny video from scratch, a social media influencer could use someone else’s audio track. It simply became easier to stand on the shoulders of giants than to reinvent the wheel.

Whether this leads to an aggregate decrease in human creativity is an open question; some have made this argument, but I’m not sure whether it’s right.4 But what’s clear is that the more everyone is always relying on the collective for everything they do, the less individual effort matters. In the Industrial Age, we valorized individual heroics — the brilliant scientist, the iconoclastic writer, the contrarian entrepreneur, the bold activist leader. In an age when it’s always easier to rely on the wisdom of crowds, those heroes matter less.

Compare the activists of the 2010s to the activists of the mid 20th century. The 20th century produced Black activist leaders like MLK, John Lewis, Malcolm X, Rosa Parks, Bobby Seale, and many others. But who were the equivalent heroes of the Black Lives Matter movement of the 2010s? There were none.5 The movement was an organic crowd, birthed by social media memes instead of by rousing speeches. Each individual activist made tiny incremental contributions, and the movement rolled forward as a headless, collective mass.

Or consider science and technology in the age of the internet. China is now probably the world’s leader in scientific research, but it’s hard to name any big significant breakthrough that has come out of China in recent years; the innovations are important but overwhelmingly incremental. Even in the U.S., where incentives for breakthroughs are a little better, science has become notably less “disruptive” in recent years. Some of this may be because humans have already picked the low-hanging fruit of science, and some might be because of the increasing “burden of knowledge” for young researchers to get up to speed. But some might simply be because an age of seamless global information transmission makes it easier for researchers to get “base hits” while leaving the cost of “home runs” the same.

Even AI, the great breakthrough of the age, has been a massive collective effort more than the inspiration of a few geniuses. Even the people who have received the greatest honors for developing AI — Geoffrey Hinton, Yann LeCun, etc. — are not really regarded as the “inventors” of the technology. Towering figures are still somewhat common in biology — Kariko and Weissman, Doudna and Charpentier, Feng Zhang, Allison & Honjo, David Liu — but in the age of the internet, research is becoming a more collective enterprise.

And all that was before generative AI. Large language models are trained on the collected writings of humankind; they are an expression of the aggregated wisdom of our species’ collective past. When you ask a question of ChatGPT or DeepSeek, you’re essentially consulting the spirits of the ancestors.6

As with the internet, it’s unclear whether LLMs will make humanity more creative as a whole, or less. My bet is strongly on “more”. But at the individual level, AI substitutes for our own creative efforts. Kosmyna et al. (2025) recently did an experiment showing that people who use ChatGPT to help them write essays end up with weaker individual cognitive skills:

This study explores the neural and behavioral consequences of LLM-assisted essay writing. Participants were divided into three groups: LLM, Search Engine, and Brain-only (no tools)…EEG revealed significant differences in brain connectivity: Brain-only participants exhibited the strongest, most distributed networks; Search Engine users showed moderate engagement; and LLM users displayed the weakest connectivity. Cognitive activity scaled down in relation to external tool use…LLM users also struggled to accurately quote their own work. While LLMs offer immediate convenience, our findings highlight potential cognitive costs. Over four months, LLM users consistently underperformed at neural, linguistic, and behavioral levels. These results raise concerns about the long-term educational implications of LLM reliance and underscore the need for deeper inquiry into AI's role in learning.

This is unsurprising. Pulling a plow yourself will make you stronger than driving a tractor, and using a slide rule will make you better at mental arithmetic than using a hand calculator. As Tyler Cowen points out, Kosmyna et al.’s result doesn’t mean that AI is reducing humanity’s overall creative capabilities:

If you look only at the mental energy saved through LLM use, in the context of an artificially generated and controlled experiment, it will seem we are thinking less and becoming mentally lazy…But you also have to consider, in a real-world context, what we do with all that liberated time and mental energy…

There are numerous ways people can and do use large language models to make themselves smarter. They can ask it to criticize their work…They can argue and debate with it, or they can use it to learn which books to read or which medieval church to visit.

This is true. Using machine tools instead of manual ones may make our biceps weaker, but it makes us stronger and more productive as a species.

Still, if most of human productivity consists of calling up LLMs, it means that collective effort — centuries of past individual creativity crystallized in the weights of the models — is being substituted for individual heroics. As with the internet, humanity as a whole grows more powerful by becoming walking terminals of the world-mind. The age of the great heroes — of the Albert Einsteins and the Martin Luther Kings, and perhaps even of the Elon Musks — may soon be over.

Thus, dimly and through the fog, we can begin to perceive the shape of the future that the posthuman age will take. As humanity becomes more tightly bound into a single digital collective, we find that we desire offline families less and less. As we gradually abandon reproduction, there are fewer and fewer of us, forcing us to cling even more tightly to the online collective — to spend more of our time online, to take solace in the ever-denser core of the final global village. The god-mind of that collective delivers us riches undreamt of by our ancestors, but we enjoy that bounty in solitude as we wirehead into the hive mind for a bit of company.

When I write it out that way, it sounds terrifying. And yet day by day, watching the latest TikTok trend, or making bad jokes on X, or asking ChatGPT to teach me about Mongol history, the slide into posthumanity feels pleasant and warm. Perhaps we are no stranger than our grandparents would have seemed to their own grandparents who grew up on premodern farms. After all, aliens never call themselves “aliens”…they call themselves “us”.

I know “children per woman” is a little sexist, but this is how they measure things.

This depends on the assumption that new ideas don’t build on themselves exponentially quickly. So far, that has proven to be the case — in simple terms, it looks as though we pick the “low-hanging fruit” of scientific discovery and technological invention, and future advances become more expensive in terms of time, money, and brain power.

At that point, either countries will collapse, or decide to cut large numbers of old people off. If countries collapse, then parents will once again be dependent on their kids, and fertility will probably recover to replacement level. If countries decide to cut old people off of benefits, they’ll probably start by cutting off the childless, since childless old people don’t have kids who can riot and revolt in anger. Either way, the economic future for childless people 50 or 100 years from now doesn’t look great.

There are actually lots of effects to think about here, and the topic deserves a much longer post all to itself. For one thing, there’s the question of whether the boost to individual innovation created by the availability of collective knowledge outweighs the spillover benefit created when each individual innovator had to spend time “reinventing the wheel” and doing it a little differently than everyone else. Also, there’s the question of whether any decrease in individual creative output per hour is outweighed by an increase in the total number of hours spent in creative pursuits — when I was a kid, kids went to the mall and hung out instead of making short videos and memes.

There were important writers in the BLM movement — Ta-Nehisi Coates, Ibram Kendi, and Nikole Hannah-Jones, to name just three. Though it’s worth noting that all were eventually hounded out of the public eye to varying degrees by collective social media backlash, unlike similar famous Black writers of the 60s and 70s.

Here are ChatGPT o3’s thoughts on this post:

The post’s central insight is that qualitative transformations in how humans live can be as epoch-making as huge jumps in measured GDP. You persuasively connect today’s two most powerful under-the-radar shifts—sub-replacement fertility and pervasive digital connectedness—to that earlier shock of the Industrial Revolution. Where the essay really shines is in showing how these trends might reinforce each other: shrinking, aging societies could grow ever more dependent on “hive-mind” tools like LLMs, which in turn further reduce the incentives (and maybe even the desire) to form families. That nested-feedback dynamic feels original and is a useful corrective to simple “AI will save us” optimism.

A second strength is the sober treatment of demographic math. By foregrounding Fernandez-Villaverde’s critique of the U.N. projections, you highlight the systemic risk that comes from repeatedly overestimating births. Framing the second fertility transition as the real discontinuity—shifting us from stable to vanishing populations—captures the scale of what’s at stake better than the usual laments about aging. Linking this directly to growth theory (Jones) and to the fiscal unsustainability of pay-as-you-go pensions sets up the reader to grasp why even dramatic productivity gains may not offset the drag.

Where I’m less convinced is on the inevitability of coercive pronatal policy and the eclipse of individual creativity. The essay nods at alternative levers (housing costs, gender-equality reforms, immigration, delayed retirement) but then leaps to dystopian scenarios without fully exploring those options or the empirical record of mixed-strategy success stories (e.g., France, Québec, parts of Scandinavia). Likewise, while the collective nature of internet-era innovation is undeniable, history––from Gutenberg to industrial R&D labs––suggests that new platforms often shift rather than erase individual heroism (think AlphaFold or Covid mRNA vaccines). Recognizing that possibility would temper the gloom and leave space for agency—exactly what a post meant to provoke action, not resignation, might need.

The spirits of the ancestors have spoken! In accordance with the model’s advice, I’ll write a follow-up post about how individual humans can still be high-leverage, important figures in the age of AI and the internet.

Reading this, I keep circling back to the massive opportunity cost that modern fertility imposes specifically on women. We rightly talk about the economics of aging, but less about how much productive potential and personal freedom is still tied up in pregnancy and childbirth. If we’re serious about wanting to sustain replacement-level birth rates without forcing women to give up ever more years of health, income, and autonomy, then artificial wombs feel almost inevitable — or at least worth far more investment and serious attention than they get now.

If the Industrial Revolution’s legacy was freeing humans from subsistence labor, maybe a comparable leap would be freeing women from the biological costs of reproduction. It’s not clear to me how else we expect to solve the math Noah lays out without resorting to draconian pronatal policies.

If we want pro natalist outcomes, we are going to have to massively rejigger society to make the cost of having children much lower and the social scrutiny around children lower.