On immigration, what Americans want is democratic control

Nations - even democratic ones - are exclusive clubs. And that's OK.

You know, it occurs to me that I haven’t seen any signs of the big illegal immigration wave in San Francisco.

If you read the news, you know that since around the time Biden took office (actually since slightly earlier, but no one likes to talk about that), there has been a giant unprecedented flood of people coming illegally across the U.S. border:

But I haven’t seen it in my back yard. Back in the early 2000s, at the crest of the last great wave of illegal immigration, I saw it everywhere — guys standing in line for day labor and hanging out in the park and working on people’s lawns. I met illegal immigrants. But now, nothing. San Francisco is a deep blue sanctuary city in a deep blue state with a Mexican border, and yet I don’t see anything like what I saw 20 years ago.

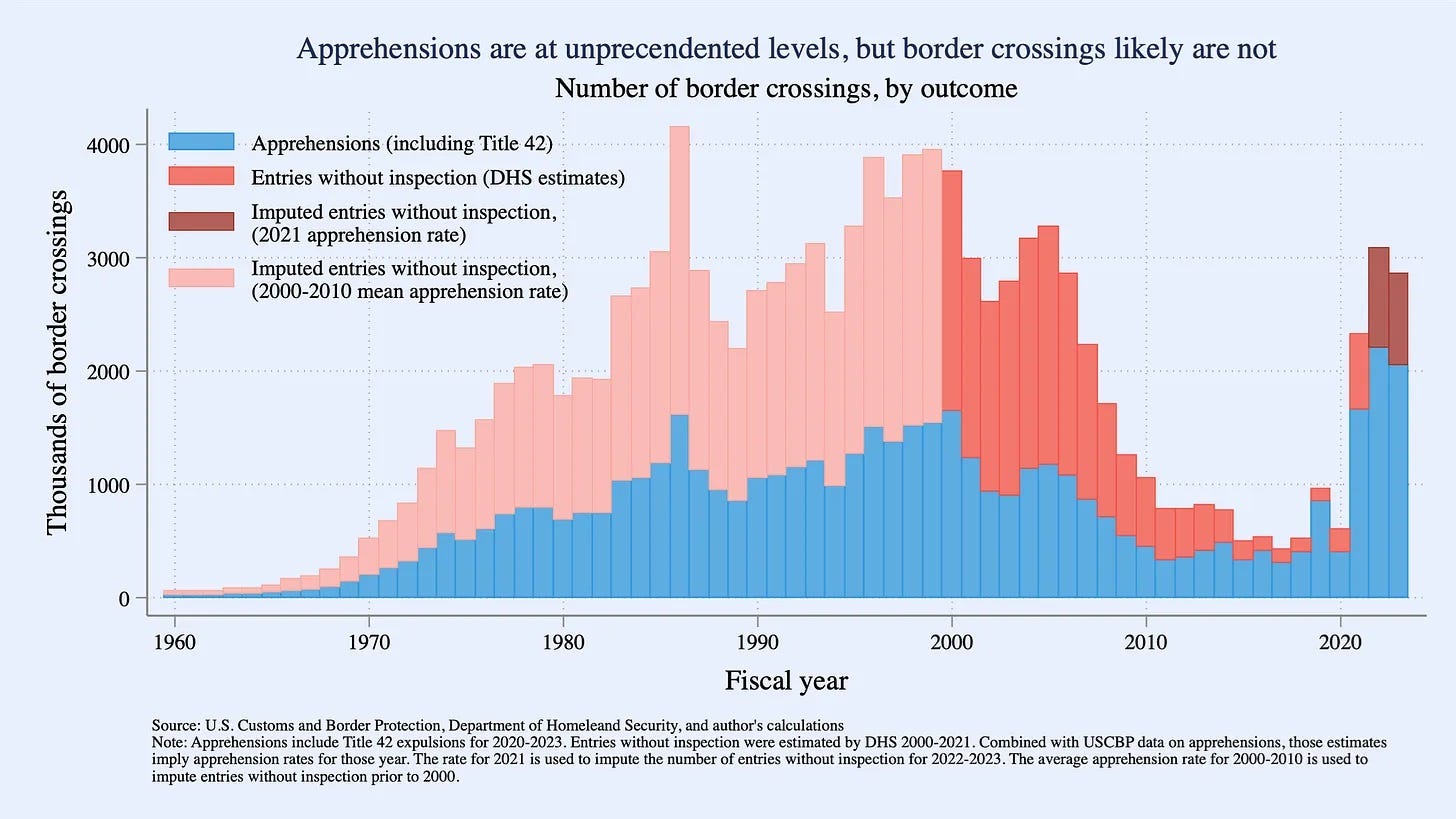

Part of this, of course, is because illegal immigration was actually a lot higher in the 90s and early 2000s than the apprehension numbers recorded at the time:

Back then, illegal immigrants avoided being caught; now they intentionally turn themselves in, in order to get an asylum hearing. So this spike has actually been smaller than the giant surge of earlier decades.

On top of that, many of the people apprehended now get kicked out of the country when their asylum is denied; that didn’t happen 20 years ago, because illegal immigrants weren’t applying for asylum. So we don’t have nearly as huge of a buildup of people staying in the country long-term. More sober estimates are that we have about 4.7 million new “illegal” immigrants since 2020.

Now, I certainly don’t want to claim that the border flood is fake. 4.7 million people in five years is a lot! Obviously it’s having a big impact somewhere — for example, NYC, where red-state governors bused many of the asylum-seekers, and which has experienced an anti-immigration backlash as a result of the strain on city services. And also the border counties, of course, whose capacity has also been overloaded.

My point, instead, is that most Americans are not in those places. Most of them are in my situation. The border crisis and the asylum flood are something that’s happening to someone else’s community. It’s a distant thing they form opinions about after reading the news, like the Ukraine War or the federal deficit.

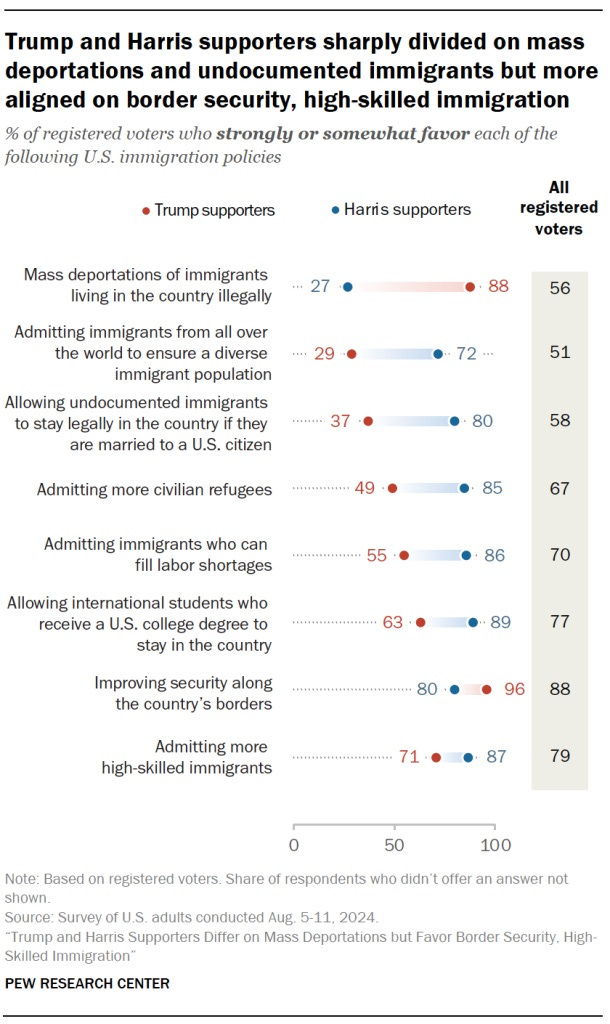

I think about this a lot when I’m trying to make sense of public opinion on immigration in America today. Majorities of both parties say they favor admitting more high-skilled immigrants and more immigrants who can fill labor shortages. 49% of Trump supporters and 85% of Harris supporters want more refugees. A majority favors allowing illegal-immigrant spouses of Americans to stay in the country. And yet a majority also favors mass deportations of illegal immigrants:

It’s not just that one poll, either. A Scripps/Ipsos poll from September found 54% in favor of mass deportation. A Harris poll finds 51% of the public, including 42% of Democrats, in support. A CBS/YouGov poll found 53% of Hispanic Americans in support of “"a new national program to deport all undocumented immigrants currently living in the U.S. illegally”, among the overall population, support was 62%.

And yet the same polls often find support for a pathway to citizenship. The Ipsos poll that found 54% in support of mass deportations found that 68% supported letting illegal immigrants stay and become citizens:

What can explain these seemingly contradictory findings? It’s tempting to write them off as social desirability bias — respondents telling pollsters what they think they’re supposed to say, instead of what they really think. But the big shifts toward mass deportation in the polls since 2020, along with the lack of a shift away from various pro-immigration policies, suggest that there’s something more going on here than bad survey responses.

I think the key here is that most Americans, like me, are not directly affected by the asylum flood; instead, they’re viewing the issue through the lens of their abstract principles about immigration. And those principles obviously aren’t simply pro- or anti-immigration. They are clearly subtler than that.

And I have a guess as to what they are.

Back in 2018 and 2019, I was doing research in preparation to write a book about immigration policy. Ultimately I decided to table the book idea, since the issue had become so divisive and emotional. But in the process, I did get to read almost 40 interesting books about immigration policy, history, diversity, assimilation, and so on. One particularly interesting book — though verbose and perhaps a tad pretentious — was Aristide Zolberg’s A Nation by Design: Immigration Policy in the Fashioning of America.

Zolberg’s thesis, basically, is that throughout their history, Americans have collectively shaped immigration policy to create the kind of country they wanted. Often this shaping was economic — admitting workers, recruiting the high-skilled, excluding people who might be a burden on the welfare state, etc. Sometimes it was racial/cultural, as in the restrictions on Asian immigration in the late 1800s and on South and East European immigration in the 1920s, and the repealing of those restrictions in the 1950s and 1960s. Sometimes it was political, as when suspected revolutionaries were excluded in the 1700s and suspected communists in the early 20th century, or when refugees from communist countries were admitted in the 1980s.

But the one constant is that America’s democratic polity collectively chose who to admit and who to exclude. Whether restrictive or liberal, the shaping of population inflows was always an act of democratic will. Zolberg sums up the idea when he writes: “Borders are necessary to establish and preserve distinctive communities, notably self-governing democracies.”

In other words, a nation, fundamentally, is an exclusive club. A democratic nation is one where everybody in the club gets a vote as to who else gets added. But there are still gates, and there are still gatekeepers.

Illegal immigration violates that principle, because it flouts the laws created by the democratic will of the citizenry. Even if Americans would let someone in given the choice, they don’t want that person coming in without their say-so. This can potentially explain why a path to citizenship and mass deportation both poll well — the first represents Americans collectively granting people their permission to stay, while the second represents appropriate consequences for people who broke the rules. They can actually be seen as representing the same principle: “Only those who are granted permission to stay by the democratic will of the American people get to stay.”

Gregory Conti makes exactly this argument in a recent article in Compact magazine:

The concern is that immigration is undermining authentic democratic self-rule…For whatever one thinks about the substance of the issue—whether one thinks immigration is a net-positive or net-negative, or whether some kinds of immigration are the one and some the other—it is an indubitable fact that policies around immigration, naturalization, and pathways to citizenship do greatly affect the nature of the sovereign people…Immigration and naturalization policy determine who will join the rank of citizen, and therefore, in a democratic country, who will participate in the exercise of popular sovereignty…

[The] crux is the effect that immigration has on the composition of the citizenry, which in a democracy is meant to be sovereign…If the people are not fit to determine who will become their fellow-citizens, why should we think they are fit to do anything at all?

This principle may seem arbitrary when you think about it in the abstract sense. It’s easy to ask abstract questions like “Why does one group of people get to squat on a piece of land and declare it off-limits to others?”. But like it or not, nation-states are the only workable arrangement for providing public goods and political stability that humankind has discovered in the modern era. And borders are an essential, inalienable part of what it means to be a nation-state.

Some progressives have always challenged that idea, and in the 2010s, these challenges spilled into the national discourse. The book This Land is Our Land: An Immigrant’s Manifesto, by Suketu Mehta, explicitly argues that European countries and their offshoots like America are morally obligated to take in immigrants as reparations for European colonialism.1 The idea that this moral obligation transcends or binds the democratic popular will of those countries is a direct challenge to the idea of a nation on a exclusive club. Leftists, of course, go even further, viewing the U.S. and some other nations as “settler colonies” whose populations lack the historical legitimacy to create borders on “stolen land”.

The asylum flood seems also to violate Zolberg’s principle of democratic exclusivity, although this is murkier because most Americans don’t actually understand what’s going on. What’s actually going on is that the U.S. wrote its asylum law to follow the 1967 version of the UN Convention on the Status of Refugees, which states that people who cross the border illegally are entitled to asylum hearings. These asylum seekers exist in a gray zone between “legal” and “illegal” immigration — they’re illegal when they cross the border and turn themselves in, then they’re legal while they await their asylum hearing, then if they get denied asylum (as most do) and stay in the country anyway they’re illegal again.

Most Americans simply do not understand how that system works. If they did understand, they’d probably vote to change the asylum law to deny hearings to — or at least penalize — people who crossed illegally. Meanwhile, among the few Americans who do understand how this system works — lawyers, policymakers, and various NGOs — there’s little appetite to reform the system. As a result, the American public sort of vaguely senses that its democratic will is being violated, but doesn’t exactly know how. And so general anger builds.

That anger now threatens to catapult Donald Trump back into the presidency, despite his coup attempt in 2020/21, despite the obvious chaos and darkness of his ideology, despite his personal corruption and bad morals, despite his unworkable policy plans, despite everything. Voters are mad about the recent memory of inflation, of course, but they’re also mad about the asylum flood:

The Democrats know this, of course, which is why they have pivoted in a more restrictionist direction in the past year. Biden has begun to enforce Trump-like asylum rules, which may be struck down by the courts, but which are undeniably having an effect in terms of curbing the asylum flood. Now, when Trump challenges Harris on immigration, her defense is not to embrace the current asylum system, but rather to point out that Trump scuttled a tough bipartisan border bill.

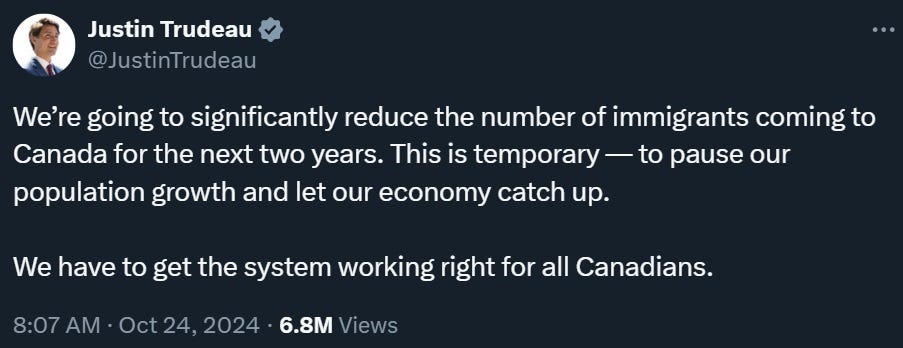

Nor is America the only country where popular democratic will has bucked against permissive immigration rules imposed by elites. I’ve long touted Canada as the world’s most pro-immigration country, and as of 2019 both the polls and policies bore that out. But in the last two years Justin Trudeau’s government has admitted a large surge of asylum-seekers, alongside a bigger and longer-term increase in temporary work permits. This was a change from Canada’s traditional policy of focusing primarily on attracting mostly high-skilled permanent residents.

And there was a big turnaround in sentiment, with the majority flipping toward accepting fewer immigrants:

Trudeau’s own popularity has hit rock bottom. As a result, he’s now pivoting to immigration restriction:

[I]n recent months, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has said he intends to significantly cut the number of immigrants allowed in Canada as public concern grows over inaccessible social services, high costs of living and unaffordable housing…It is a major shift for both the country and Trudeau, who ran in 2015 on a platform of embracing multiculturalism as a key part of Canadian identity…His government has relied on ambitious immigration targets to fuel economic growth…In the face of criticism and plummeting approval ratings, the prime minister now says that his government miscalculated, and that Canada needs to “stabilise” its population growth so that public infrastructure can keep up…On Thursday, Trudeau and Immigration Minister Marc Miller presented their most stringent immigration cutbacks yet - a 21% reduction of permanent residents accepted into the country in 2025.

Here is what he tweeted:

It’s not clear that Trudeau understands why sentiment on immigration has soured in his country2, or that this move will save his party in the elections next year. But it’s another example of popular will in a generally pro-immigrant democracy rising up to remind the elite of who actually decides who gets in to the country.

Many progressives will interpret these trends as a rise in xenophobia, white supremacy, etc. That interpretation is a mistake that will cost progressives dearly if they persist in making it. A xenophobic country would not favor the admission of more refugees, laborers, and skilled immigrants, as America does. Nor would a white supremacist country, since these immigrants are mostly not white. The majority of Americans disagrees with with Trump’s position that undocumented immigrants are an “invasion” or a form of “poison”.

Trump and his movement are certainly xenophobic. But if the median American voter in Pennsylvania and Michigan and North Carolina sends Trump back to the presidency a week from now, it won’t be because they share that sentiment. Nor will it be because immigrants are actually flooding their neighborhoods and causing problems. It will be because they demand democratic control over immigration as a matter of principle. Trump promises to make America, at least temporarily, a more bigoted, atavistic, cruel, small-minded nation — but in the eyes of many, that’s preferable to not having a nation at all.

The solution, of course, is for Democrats — and responsible conservatives, and political leaders in general — to change America’s immigration system to make it more congruent with the democratic will. The asylum loophole should be abolished — crossing the border illegally should not be rewarded with the chance to stay in the country while awaiting an asylum hearing. Accepting lots of people into the country legally is fine — I will continue support that, and I think Americans in general will agree with me. But if the American people have decreed that a person should not get in, they should not get in. And Democrats should make it clear to the public, with loud and certain rhetoric, that this is being done.

The alternative is a country that turns against immigration in general for a long time, as we did in the 1920s. That is not something I want to see happen. But for immigration to be preserved, it must come fully under democratic control.

Mehta’s book came highly recommended by Chris Hayes, an anchor for MSBNC. I was very surprised that he would endorse a book that argued for immigration-as-reparations. The 2010s were a strange time.

Note that Trudeau is cutting permanent residents, even though the big increase has been among temporary residents.

Great article and something that most normie voters would agree with. If the Biden administration had the common sense to understand this, we wouldn't have faced the very real prospect of another Trump Presidency. They should have realized this in 2016 because immigration was one of Trump's strengths but they decided that if Trump is bad, his policies must be bad too.

This is the best article that sums up the nuances of immigration in the United States, and how some democrats’ incessant yelling that wanting immigration control was racist caused them to miss the reality that Americans don’t mind immigration but they want to be able to have a say.