At least five interesting things to start your week (#34)

Woke capital, university rigidity, social media toxicity, SUVs and pedestrians, and crime and urbanization

Hi, folks! A big and important national security bill just passed the House, containing aid for Ukraine, Taiwan, and Israel, as well as a demand that TikTok separate from its Chinese parent company. This is big news, but the bill still has to go to the Senate on Tuesday. I’ll write about it if and when it passes the Senate. In the meantime, today’s list of interesting things focuses more on domestic matters.

First, though, we have podcasts. There are two episodes of Econ 102 this week. The podcast is morphing to a Q&A format, which listeners seem to be enjoying a lot. If you want to submit questions to the show, you can email the producers at Econ102@turpentine.co.

Now, on to this week’s list of interesting things:

1. “Woke capital” thrives when competition is weak

Over the last decade, many large U.S. corporations moved away from a pure focus on the bottom line, and became more socially and politically activist — usually in a progressive direction. This phenomenon eventually became known as “woke capital”. Fan (2019) sums up the trend:

Iconic companies such as Apple, BlackRock, Delta, Google (now Alphabet), Lyft, Salesforce, and Starbucks, have recently taken very public stances on various social issues. In the past, corporations were largely silent in the face of them. Now the opposite is true—corporations play an increasingly visible role in social movements and there are times when corporations have led the discussion, particularly in areas where they have a self-interest or public opinion supports it. The enormous influence corporations wield on both the economic and social fabric of our society due to the legal framework and norms under which they operate make them uniquely positioned to affect the outcome of social movements—for better or worse.

Others scoffed at the idea, arguing that “woke capital” would fail to change society in a meaningful way.

But over the last two years or so, woke capital seems to be in retreat. ESG and DEI, two of the main corporate policies associated with the trend, have been losing popularity to some degree:

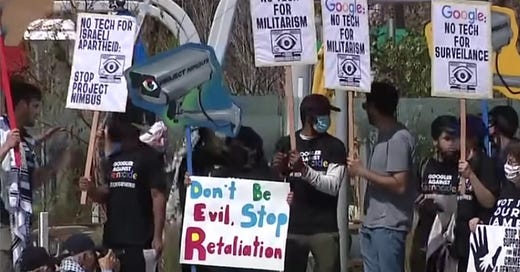

A recent incident at Google may eventually be remembered as a watershed in this process. A number of workers staged a sit-in protest over Google’s provision of cloud computing services to the Israeli government. Nine were arrested. In response, Google fired 28 employees whom it determined to be involved with the protest in some way. CEO Sundar Pichai sent out a lengthy memo to the company declaring that the company “is a business, and not a place to act in a way that disrupts co-workers or makes them feel unsafe, to attempt to use the company as a personal platform, or to fight over disruptive issues or debate politics.”

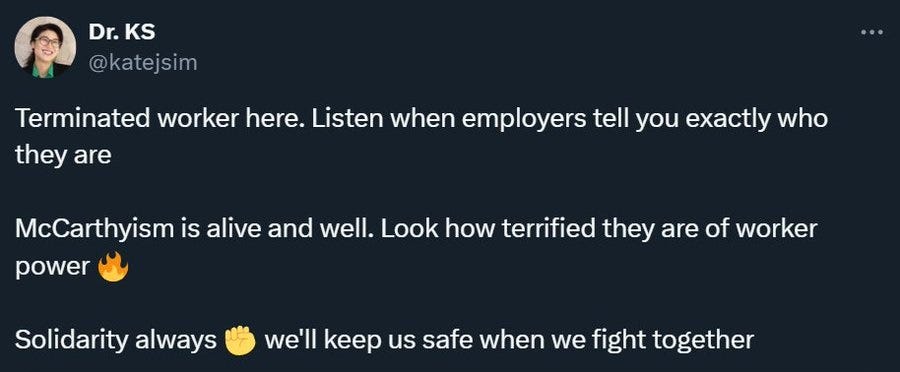

The fired workers took to social media to decry the company’s actions, with zero apparent result:

Google’s leaders were not, in fact, terrified of worker power, and had no problem declaring exactly who they are.

What explains the abrupt decline of woke capital? A general turn away from the attitudes and activism of the 2010s is probably part of it. But I think economic forces are clearly at work here too. The rise in interest rates that began in 2022 was obviously part of it, putting pressure on corporate America to increase profitability. But another factor was probably competitive pressure.

Gary Becker, the famous Chicago economist, had a theory that lack of competition allows companies the leeway to discriminate in ways that would otherwise hurt them economically. In the 70s, that mainly meant discriminating against women and minorities. In fact, there’s a decent amount of evidence in favor of that theory, as I wrote in a post two years ago:

In the 2010s, companies often chose to discriminate in favor of the activist class — hiring people whose main goal at work was to change society, rather than to make money for the company. We tend to think of the rise of monopoly power and the rise of “woke capital” as separate phenomena, but Becker’s theory suggests they were actually intimately related.

In recent years, competitive pressure has increased for companies like Google. The reinvigorated antitrust movement at the Federal Trade Commission and Justice Department is probably exerting a chilling effect on both mergers and on anticompetitive business practices. Google’s search ad monopoly has come under intense scrutiny, and is the subject of an ongoing antitrust lawsuit. In addition, the rise of generative AI is disrupting Google’s core business model, offering an alternative way to find information on the internet.

Thus, Google can no longer afford to mess around like it used to. Cutting down on employee perks is part of that. Eliminating the jobs of workers who show up to bash Google’s policies instead of making the company money is another part of it.

So although progressives tend to strongly support antitrust, especially against big tech companies, it may play a key role in sunsetting the era of “woke capital”. That would be quite an ironic turn of events.

2. Universities and the reallocation problem

Universities are a key part of the U.S. economy. They’re responsible for much of our research output and much of our human capital production. Because universities are so crucial to America’s economic machine, we support them with any number of government policies — tax exempt status, massive R&D funding, exemption from the H-1b visa cap, cheap subsidized loans for undergrads (which mostly flow directly into universities’ pockets), and so on.

So if universities’ economic productivity is suffering from structural problems, it’s a big deal. And I think that one problem we tend to overlook is that universities have difficulty reallocating resources.

For example, the University of California San Diego just announced new limits on how many people can major in computer science:

This seems a bit crazy, no? In recent years, a lot more students want to go to college to learn computer science:

So who is the university to tell them no? Universities should respond to the increasing demand for CS majors by hiring more CS profs and lecturers, and decreasing the number of teachers in the subjects that students no longer want to study.

Of course, doing that is actually pretty difficult. Not only does every department head and dean in every university lobby the administrators for more resources, but many profs and lecturers in the increasingly unpopular humanities have tenure and can’t be laid off. Faced with that constraint, universities naturally have trouble finding the money to hire new faculty to teach the STEM subjects that students increasingly want to learn.

Ultimately this will impact the nation’s supply of human capital. We need a bunch of STEM graduates to maintain a presence in industries like semiconductors, electric vehicles, machine tools and robotics, aerospace, software, and so on, we’re going to need a lot more students with STEM degrees. And American students increasingly want those STEM degrees. If universities can’t meet that demand because of their legacy commitments to economically less important sectors, that’s not just a problem for college kids — it’s a problem for the United States as a whole.

China, for its part, has no such legacy issues. Although it only has four times the population of the U.S., it graduates seven times as many engineers each year. If you feel uncomfortable reading that China graduates seven times as many engineers as the U.S. while top U.S. universities are forbidding American kids from majoring in computer science…well, you’re not alone.

3. Social media silences moderates and amplifies extremists

I often jokingly call myself a “technological determinist”, because I tend to instinctively look for technological explanations for social phenomena. So when I try to explain the explosion of social unrest that the U.S. experienced in the 2010s, I naturally tend to point the finger at social media. Back in 2017 I wrote a post about how Twitter amplifies people who just want to shout and argue (myself included, obviously):

I followed this up with a post in 2021 discussing some evidence that Twitter and other social media platforms amplify divisive voices and people with toxic, aggressive personalities:

Well, here’s a bunch more research to add to the growing pile. In a new study entitled “Inside the Funhouse Mirror Factory: How Social Media Distorts Perceptions of Norms”, Claire Robertson, Kareena del Rosario, and Jay J. Van Bavel survey the literature and find that social media discussions increase both the polarization of opinion and the perceived polarization of opinion.

Here’s an excerpt:

In online political discussions, the people who post frequently on social media are often the most ideologically extreme, (Bail, 2022; Barberá & Rivero, 2015). Indeed, a recent analysis found that 97% of political posts from Twitter/X came from just 10% of the most active users on social media, meaning that about 90% of the population's political opinions are being represented by less than 3% of tweets online (Hughes, 2019). This is a marked difference from offline polling data showing that most people are ideologically moderate, uninterested in politics, and avoid political discussions when they are able (American National Election Studies, 2021; Converse, 1964; Krupnikov, 2022). This renders moderate opinions effectively invisible on social media, leaving the most extreme perspectives most visible for users…

Receiving biased inputs from the online environment can lead to extremely biased outputs…People base their perception of norms on an unrepresentative sample of opinions and images leading to a distorted view of social norms.

And here is a graph that shows how the effect works:

Anyway, it’s really just the exact thing I described in my “Shouting Class” posts. Normal people log on to Twitter and they see a small number of highly engaged extremists engaging in constant shouting battles. This makes people think the country is more polarized than it really is, which scares them and makes them more likely to fear and distrust the opposing political party.

This seems like a major technological problem that liberal societies haven’t yet figured out how to solve. I hope we find something better than China’s “solution” of totalitarian information control.

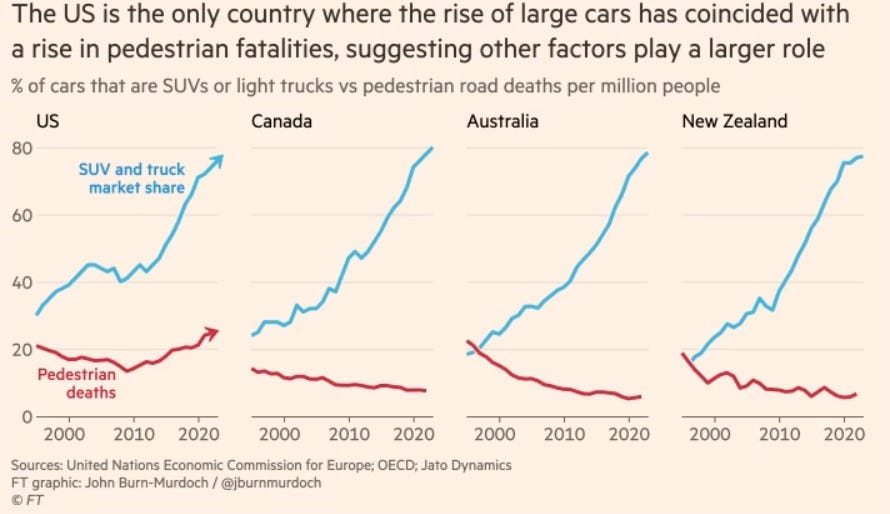

4. No, U.S. pedestrian deaths aren’t due to bigger vehicles

Pedestrian deaths have soared in the U.S. in recent years. A lot of urbanists believe that this is due to the fact that Americans have been driving bigger, heavier cars. That turns out not to be the reason.

A year ago, a whole bunch of people on Twitter confidently, even aggressively told me that of course heavier cars are more dangerous, that this is just physics. After all, force = mass x acceleration, right? I patiently tried to explain to these people that even a very light, small car is so much heavier than a human that a collision between any car and a pedestrian is basically like a human falling onto the ground. No one listened. So Andy Masley actually went through the numbers and showed that heavier vehicle weight makes a negligible difference:

But what about vehicle size and shape? After realizing that the weight factor wasn’t important, urbanists defended their thesis by pointing to research showing that vehicles with flat, high hoods — SUVs and trucks — are deadlier to pedestrians, because they’re more likely to hit them in the torso than in the legs, and because they cause pedestrians to bounce off the hood instead of rolling over it.

But a bunch of evidence shows that this factor, while real, is relatively minor. For one thing, as John Burn-Murdoch points out, people in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand have been going even more crazy for SUVs, and yet their pedestrian deaths have continued to go down:

Now, it’s possible that these other countries were just working very hard to lower pedestrian deaths at the same time, compensating for the increase in SUVs. But there’s plenty of other evidence here as well.

Tyndall (2021) estimates that the effect of SUVs is modest; replacing all SUVs with cars would reduce U.S. pedestrian deaths by only 9.5% — not nothing, to be sure, but not anywhere big enough of an effect to cause the increase in deaths since 2009. Tyndall also points out that even as SUVs have grown in popularity, minivans have become less common, which partially canceled out the effect of SUVs:

Meanwhile, a New York times analysis found that the increase in U.S. pedestrian deaths has been exclusively a nighttime phenomenon:

Since SUVs are the same shape whether the sun is shining or not, the lopsidedness of this increase strongly suggests that deadlier vehicle shapes are not the big culprit here.

So no, SUVs aren’t a big reason for the rise in pedestrian deaths in the U.S. That doesn’t mean SUVs are good — they guzzle more gas, take up more space, etc. But urbanists need to look realize that not every road-related problem is caused by their favorite villain.

(As for what did cause the increase in pedestrian deaths, we don’t really know that yet.)

5. Crime is bad for urbanism

Many American progressives are urbanists, who want greater urban density, more walkability, more public transit, etc. And many American progressives are in favor of a less punitive attitude toward crime, with less incarceration, less policing, and fewer penalties for drugs. But those two objectives are probably fundamentally in conflict.

In my posts about why Japanese cities are so excellent, one factor I’ve emphasized is public safety; Japanese cities are great environments because violent crime is incredibly low. Well, there’s evidence in favor of that argument.

Donovan et al. (2024) find that local crime consistently lowers rents in New Zealand. To isolate causality — i.e., to make sure that crime and lower rents in a neighborhood aren’t both just caused by a third factor, such as poverty — they look at the allocation of additional police to various neighborhoods under a 2018 New Zealand policing expansion. There’s very good evidence that increased policing decreases crime, and Donovan et al. find the same. This allows them to show that crime causally decreases rents. (They also use another alternative technique to show causality, but I won’t go into that here.)

Anyway, lower rents are due to lower demand. So the fact that crime makes rent fall means that people don’t want to live in high-crime neighborhoods. Donovan et al. theorize that this leads to noticeable reductions in cities’ agglomeration economies — i.e., the economic benefit of density.

So progressive urbanists who dream of dense, walkable, transit-rich cities need to understand that there’s a tradeoff here. A more permissive attitude toward crime is going to make people move out to the suburbs — not just “white flight”, but Americans of all races. Policing and incarceration aren’t the whole solution, of course, and American police forces still do have plenty of problems. But a refusal to police streets and lock up criminals is going to make it difficult to create the kinds of cities that European and Asian countries enjoy.

Not impossible, of course — NYC does exist. But it’s no coincidence that our one truly dense, walkable metropolis is also among the safest major cities, and one of the most heavily policed. Sometimes, reality forces unfortunate tradeoffs upon us, and we have to prioritize.

It's not just in teaching that universities suffer extreme allocation inefficiencies. It also shows up in the difficulties they have in organizing even very basic cross-field or cross-institutional research collaboration. A couple of examples from recent years that stick in my mind:

1. Public health researchers recommend extremely destructive policies, then turn around and say "you can't expect us to think about the economic impacts of our suggestions/demands, we aren't economists". Alternatively, profs like Ferguson write code full of bugs so it doesn't model what they think it's modeling, and then say "you can't expect us to write working code, we aren't computer scientists". Imperial College London even said to the British press "epidemiology is not a subfield of computer science" in defense of Ferguson's crap work.

If you say, but you work down the hall from economists/computer scientists, so why didn't you talk to them ... well academics just look at you blankly. The thought that they might go build a team with the right mix of specialisms to answer a specific question just doesn't seem to occur to them, even though they easily could. This is a big driver of the replication crisis too, because universities are full of "scientists" who struggle so badly with statistics and coding that they produce incorrect papers all the time, and it becomes normalized. They can't recruit professionals to help them because they don't pay enough and they don't pay enough because they allocate their resources to maximizing quantity (measurable) over quality (not measurable).

2. In computer science it's not all roses either. Billions of dollars flow into universities via grants, yet when it comes to fields like AI they constantly plead poverty and that it's too hard to compete with corporate labs. Why don't they pool resources, like the physics guys do in order to build particle accelerators? Again, cultural issues. There's a limited number of names that go on a paper, a limited amount of reputation to go around, and pooling resources means most researchers will toil on unglamorous work. So they prefer to split up their resources over gazillions of tiny teams that mostly produce useless or highly derivative "me too" output.

The result is that universities *appear* to be highly productive and important, if you measure by their preferred metrics like paper production. If you measure them by actual real world impact of implemented research outcomes, they are well behind and falling further.

China is no better by the way. They produce more papers than America does now but nobody reads them, not even in China. Way too much outright fakery.

Former Googler here. Competition is definitely part of the picture, but scale- and corporate age-driven culture change is also part of it and would have happened anyway.

Google in the 2000s and 2010s had a very, very university-like culture. That was partly because the founders came out of grad school and hired a bunch of academics, partly because the smartest and most productive people of that time appreciated the non-material returns of a collegiate atmosphere, so pairing that with a fat paycheck made for an exceptionally good recruiting pitch. And as we know, collegiate culture has upsides and downsides. Allowing for open-ended exploration that can lead to amazing innovation is part of the upside; tolerating full-of-BS entitled activists is part of the downside.

In the late 2010s senior execs began systematically eroding the good parts. 20% projects got less respected and less common, internal informational openness got restricted in response to leaks, and the performance review/promotion cycle led people more and more to do box-checking things instead of innovative things. Pressure from competitors (and poorly executed fear responses to competitors) was indeed a major motivator for these changes, but I think some change like this was probably inevitable as the scale of the company went from ~10K to ~100K. It's just too hard to weed out freeloaders, rest-and-vesters, leakers, and other abusers reliably enough at that larger scale to maintain the extraordinarily high level of trust that made the "good parts of college" work so well before. I'm amazed they did it at 10K; Google ~2010ish was the most astonishingly functional and humane institution I've ever been a part of and one of the best I've ever known to exist in history.

Anyway, the point is: once the good parts went by the wayside, there was no longer any upside to keeping the bad parts. The activist clowns were no longer a price that had to be paid for letting people think and explore freely, because people weren't allowed to do those things anymore anyway. So the ROI balance tipped in favor of a crackdown.