At least five interesting things: You Can't Just Do Things edition (#69)

Cash benefits; The college shakeout; Chinese involution; The UK's energy bust; Turkey's central bank; Tariffs

Sorry for the slow publishing this week…my rabbit had some health issues! But he’s fine now, thankfully.

Anyway, I have a fun video debate for you today! It’s me versus Oren Cass, on the topic of tariffs!

I also have an episode of Econ 102, where Erik and I discuss the question of who will ultimately profit from the AI boom (something I plan to write more about in the coming months):

Anyway, on to this week’s list of interesting things! This week’s theme is reality interfering with the best-laid plans of policy wonks and populists alike…

1. Cash won’t solve all of poor people’s problems

For years, I’ve been a big advocate of the “just give people cash” theory of the welfare state. I’ve written a bunch of articles in support of the idea. My reasons are:

Cash benefits are much easier to administer than other kinds of benefits.

A lot of economic research found that unconditional cash benefits don’t do much harm to the labor market — i.e., people generally don’t stop working when they start getting checks in the mail. The research also found that people don’t tend to fritter away the cash on drugs and alcohol, as many conservatives fear.

Unconditional cash benefits can reach a lot of people who fall through the cracks of other welfare programs — for example, people who can’t earn any income (and so can’t get the EITC) or don’t have kids (and so can’t get the Child Tax Credit).

In the late 1990s, America mostly canceled a traditional welfare program (AFDC/TANF) and replaced it with some cash-type programs (EITC and CTC), and the experiment went very well.

However, in recent years, some new research has come out that tempered my enthusiasm for the cash benefit revolution. First, a basic income trial in Denver failed to decrease homelessness, which is one thing you’d really like to see basic income do. Then, an even bigger basic income trial in Texas and Illinois found that just $1000 a month caused 2% of people to stop working — a very big disemployment effect, contradicting the results of earlier studies. Worryingly, this study is much more believable than any of the more optimistic studies, since it’s a very large randomized controlled trial. (Of course, it’s just one study; the papers showing little effect are still more numerous, even if no single one is as reliable.)

Meanwhile, a lot of these studies are finding that cash benefits aren’t really doing much to improve quality of life for the people who get the cash. You can measure various things we think curing poverty ought to improve, like health, education, employment, housing, etc. And unfortunately, these recent studies show that cash benefits aren’t making those indicators look much better. Kelsey Piper recently wrote an article in The Argument summing up some of this evidence. Some key excerpts:

The team behind Baby’s First Years…gave their control group $20 per month and their experimental group $333 per month. They recruited low-income mothers…The experimental group had more money (as you would expect) and worked a little less (but it’s probably good if mothers of young babies can cut back on hours slightly). They also spent slightly more money on stuff for their kids.

But there was not much else. The cash transfers did not improve maternal health outcomes or child health outcomes. They had no effect on stress, depression, body mass index, how often children got sick or the children’s overall health. They did not improve mothers’ self-reported relationship quality or measures of psychological distress. There was no effect on child development…

A Compton, California, RCT tried $500 per month for two years. They found “no significant effects of the transfers on labor supply; assets; psychological well-being; financial security; or food insecurity.” The biggest effect they found was on other income sources: The groups receiving transfers worked fewer hours or got paid less than people in the control group. The lost nontransfer income averaged $333 a month…

The OpenResearch unconditional income study tried $1,000 per month for three years, while the control group got $50 per month. They found that participants worked less — but nothing else improved. Not their health, not their sleep, not their jobs, not their education, and not even time spent with their children. They did experience a reduction in stress at the start of the study, but it quickly went away…

Direct cash payments not making people better off is a surprising finding — and while Baby’s First Years and Compton are relatively small sums of money, OpenResearch is larger.

This is all extremely disappointing. In these well-designed real-world experiments, cash benefits are making people produce less in the market, while not really making their lives much better. And as Piper goes on to explain, nobody can really figure out why. People aren’t using the cash to buy drugs or gamble or whatever; they’re working a bit less, but mostly they’re just spending the cash on things they need. It just doesn’t make their lives look less like the lives of poor people.

Matt Bruenig, a prominent socialist advocate of cash benefits, attempted to write a rebuttal of Piper’s piece, but it wasn’t up to his usual standard of quality. Other than pointing out a study from Finland that shows more optimistic results, he didn’t really rebut the evidence that Piper brought to bear. Bruenig talks about the historical importance of Social Security and the success of Nordic countries. But these arguments miss the mark, because they don’t address the question of what additional cash benefits can do for Americans in the present day.

A more valid counterargument — and one that Bruenig touches on, but could have been a lot more explicit about — is that poor people having more cash is simply a good thing in and of itself, whether or not their kids become healthier or they get a better education or they report less depression. Being able to afford more food, more transportation, more housing, etc. makes your life better, even if it doesn’t make you lead a healthier lifestyle.

This is why I still support cash benefits. (Though the recent results on disemployment do give me pause, because economies do need to produce things in order to have things to redistribute.)

But I think the recent evidence points at a deeper truth, which is that many of the social ills we believe result from low income — drug use, poor health, broken families, violence, and so on — might not be solvable by giving people more TVs, sofas, cars, and cell phones. Material goods are important, but they aren’t everything, and we should be looking for additional ways to help poor people lead happier lives.

2. American colleges are in trouble

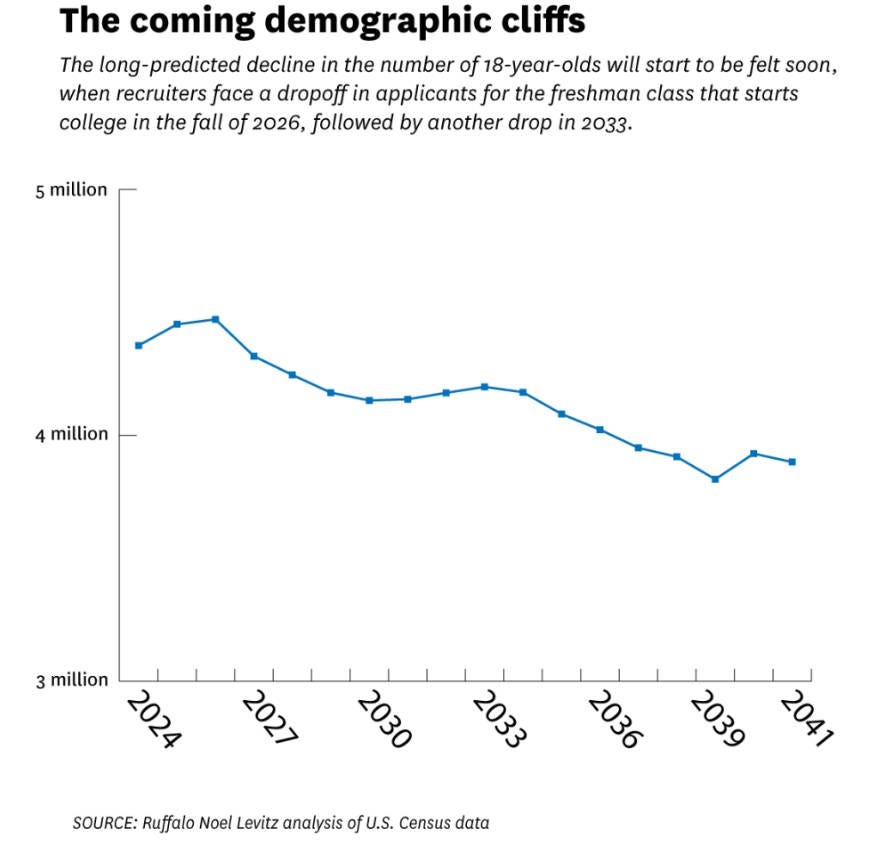

One of my long-running theses about the U.S. economy is that the higher education sector has gotten too bloated and is due for a shakeout. The most important reason is that enrollment rates are falling. That’s partly because fewer young people are choosing to go to college, but a lot of the story is just declining birth rates, leading to a dearth in the number of young people in America:

Many universities will try to fight this trend by letting in more international students. That would be a great move — and good for the country as a whole — except that the Trump administration and the Republican Party more generally are trying to push foreign students out of the country en masse. And they are succeeding — international enrollment is dropping, putting the very survival of many colleges in danger.

However, we shouldn’t let this obscure the fact that college itself is becoming a less valuable proposition for the marginal student. A new paper by Bleemer and Quincy finds that a university education isn’t nearly as good of an escalator into the middle class as it used to be. There are several reasons, but one is that students from higher-income backgrounds have been choosing more lucrative STEM majors, while students from lower-income backgrounds have been crowding into lower-value humanities majors:

We show that two recent trends in college major choice – the ‘death’ of humanities enrollment…and rising computer science enrollment – have both been driven by higher-income students…[T]he ordering across disciplines’ average wages has stayed remarkably constant over time, with humanities at the bottom and engineering and business majors earning the highest wages.

This dovetails with another trend: rampant grade inflation. Rose Horowitch recently wrote a good article about this for The Atlantic, and there’s research supporting the notion that grade inflation has been increasing steadily at American universities for some time now. Matt Yglesias argues that the problem is worse in the humanities:

An uncomfortable possibility is that many (most?) American universities have transformed themselves to act as high-value training centers for rich kids and low-value diploma mills for working-class kids. This means that the marginal students — the people who really need college the most — aren’t really getting the education they deserve. A crappy humanities diploma that employers know was essentially handed out for free will not increase your wages much in the job market, even if it has a prestigious name stamped on it.

That’s not really a service worth paying for. No wonder college tuition is falling.

3. China is starting to curb “involution”

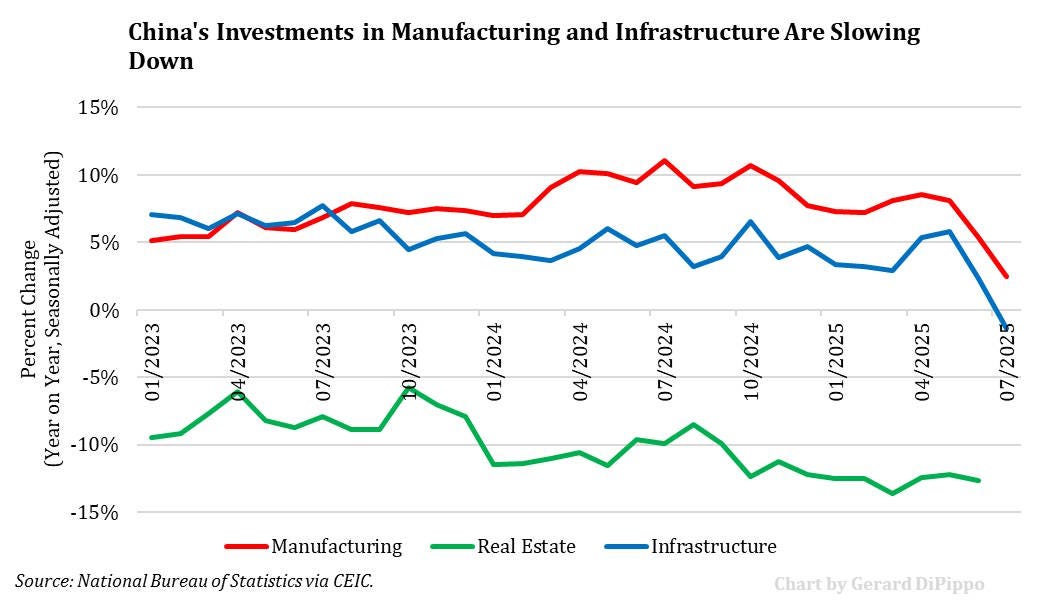

The big story of China’s economy over the last few years is that the leadership tried to replace a real estate boom with a manufacturing boom. The problem with this idea was that just producing a ton of stuff doesn’t actually mean you’re adding real economic value. So China has been paying its companies to compete each other’s profits to zero:

The Chinese word for this is “involution”.

This results in at least three problems:

You end up with a lot of junk that nobody really wants. This actually reduces productivity growth, because you’re producing a lot of stuff but it isn’t worth much to anyone.

Your companies become unprofitable, which might not bother the central planners, but certainly makes a lot of regular Chinese businesspeople very mad.

At the macroeconomic level you can get deflation from the vicious price wars, which then exacerbates the debt problem from the real estate bust.

At this point, you can do one of three things:

You can find some new underdeveloped sector of the economy to direct resources to.

You can curb production, which will raise profits and lead to more sustainable growth, but will slow growth in the short-term.

You can just keep doing what you’re doing, turning all the metals in the Earth’s crust into solar panels and electric cars and humanoid robots, like that AI that just wants to turn everything into paper clips.

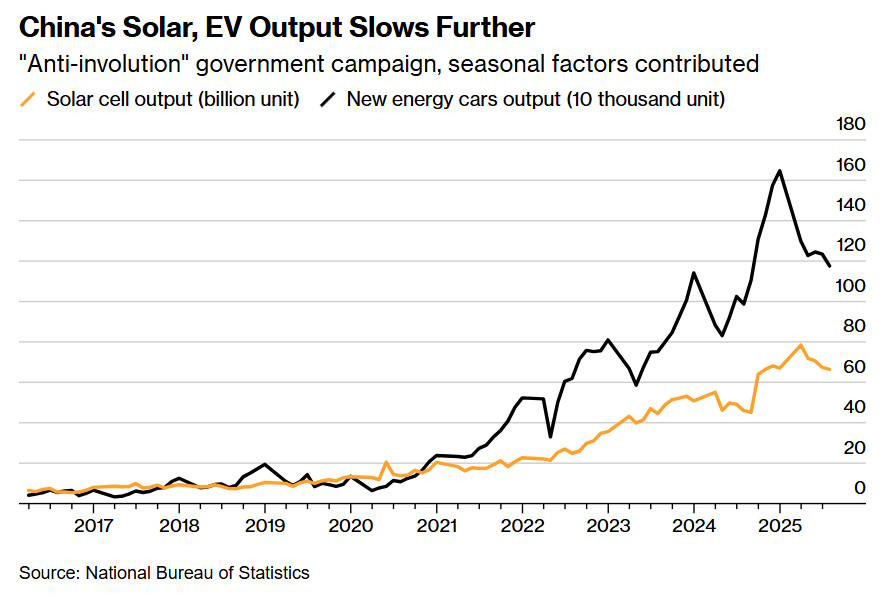

Given Xi Jinping’s track record, you might assume that he’d go for option (3). And so far there hasn’t been an all-out campaign to curb involution or to redirect resources toward the service sector (the only sector of the Chinese economy that’s still underdeveloped). But you can see the Chinese government sort of pivoting in the direction of an anti-involution policy:

And so, it seems like a pretty big deal to see China trying to crack down on its overcapacity issues in recent months. Last year, Beijing announced an “anti-involution” drive, promising to tackle gluts in new ways. These efforts seem to be gaining some additional momentum as policymakers continue to grapple with deflation and what really does look like a balance sheet recession…[J]ust today, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology vowed to “curb disorderly, low-price competition” and “encourage the orderly exit of outdated production capacity through market-based and legal approaches” in the solar industry…Beijing isn’t just trying to clamp down on disorderly expansion and unproductive competition; it’s also nudging its industries toward profit discipline, capacity rationalization, and market-driven consolidation.

No one seems to know exactly what China is doing in order to crack down on involution — they just assume the Chinese state gets what it wants from companies. But everyone seems to agree it’s real. In fact, you can see a big drop in the manufacturing investment numbers:

Of course, it’s not clear whether this is a government-directed slowdown or a market reaction to the unprofitability of the lending boom of 2022-24. But it’s notable that solar and EVs, which seem to be seeing some of the most vicious involution — with even China’s standout national champion, BYD, under intense pressure from heavily subsidized rivals — are seeing particularly large seasonal drops in production:

Whatever is causing China’s manufacturing investment to slow down, it’s definitely contributing to a slowdown in economic growth.

It turns out that Stein’s Law applies even to China’s vaunted industrial might.

4. Why conservatives fear green energy

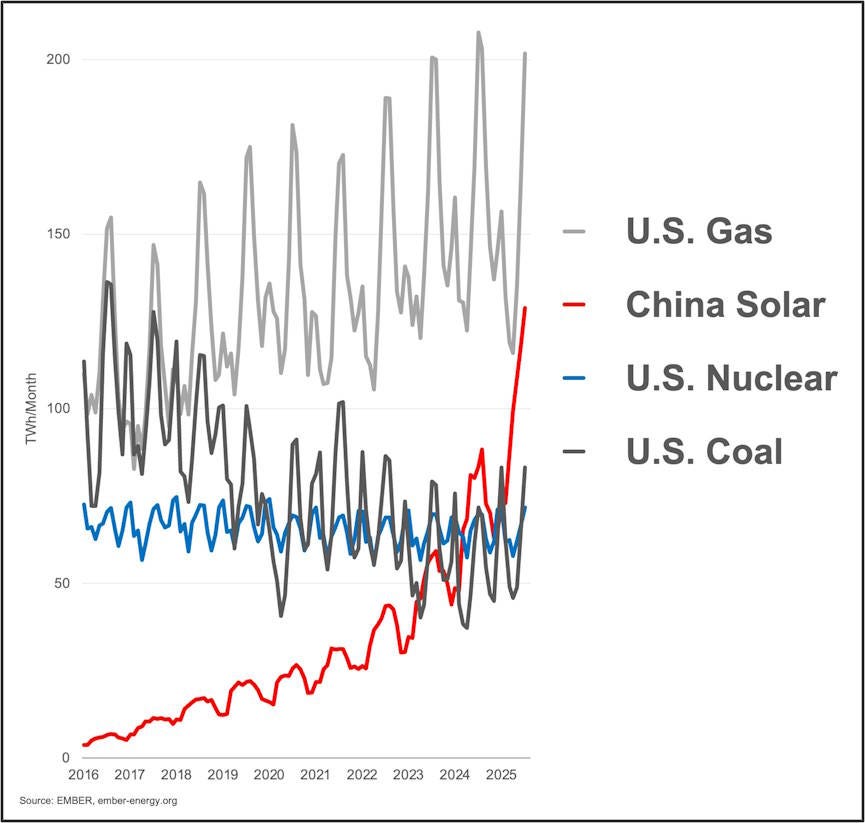

America’s right wing is kind of insane about energy. Much of the rest of the world switches to cheap solar and batteries, and China is using solar to blow past the U.S. in electricity generation:

And yet America’s right wing is waging a protracted, desperate, all-out campaign to destroy the solar industry, with Trump declaring that America will run on coal instead. In an age of cheap solar and batteries, that’s just going to contribute to America’s spiraling electricity costs, and hurt the economies of red states like Texas that have been leading the green energy boom.

So why is the right attacking cheap energy?

The answer is “culture wars”, but that’s not very satisfying. Right-wingers didn’t simply decide that solar and batteries were hippy-dippy bullshit because they didn’t like the look of solar panels and windmills! OK, a little bit of it was that, but mostly it’s because the right thinks of renewable energy as being all about climate change, rather than about securing cheap reliable supplies of electric power.

In one sense, you can’t blame the right for thinking like this — after all, climate change activists on the left pretty much only talk about solar and wind in terms of the carbon emissions they prevent (or at least, they did until recently). That sets conservatives’ alarm bells ringing, because they think of climate change primarily as something that leftists play up in order to bring down capitalism and soak the rich. The right sees green energy not as a form of abundance, but as a degrowth policy, designed to force Americans to live with less.

This is, of course, ridiculous. But it wasn’t always! There was a time, not too long ago, when solar power was much much much more expensive than it is now (and wind and batteries, too). If we had forcibly converted to solar in the 1980s, it would indeed have ruined our economy. This has only changed in the last decade, but like most people, conservatives are slow to update when the world changes.

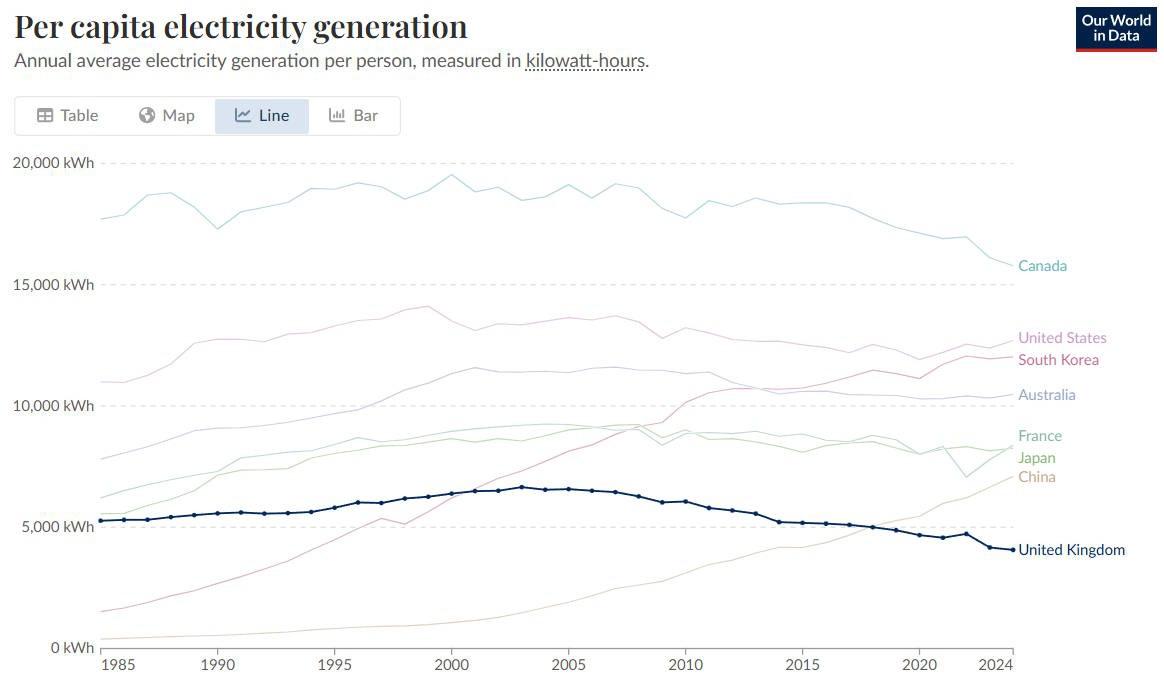

In fact, to see how a mismanaged and misguided push for green energy can hurt a country’s economy, you have to look no further than the UK. Over the past 20 years, the UK’s energy use per capita has fallen steadily, putting it well behind China and other rich countries:

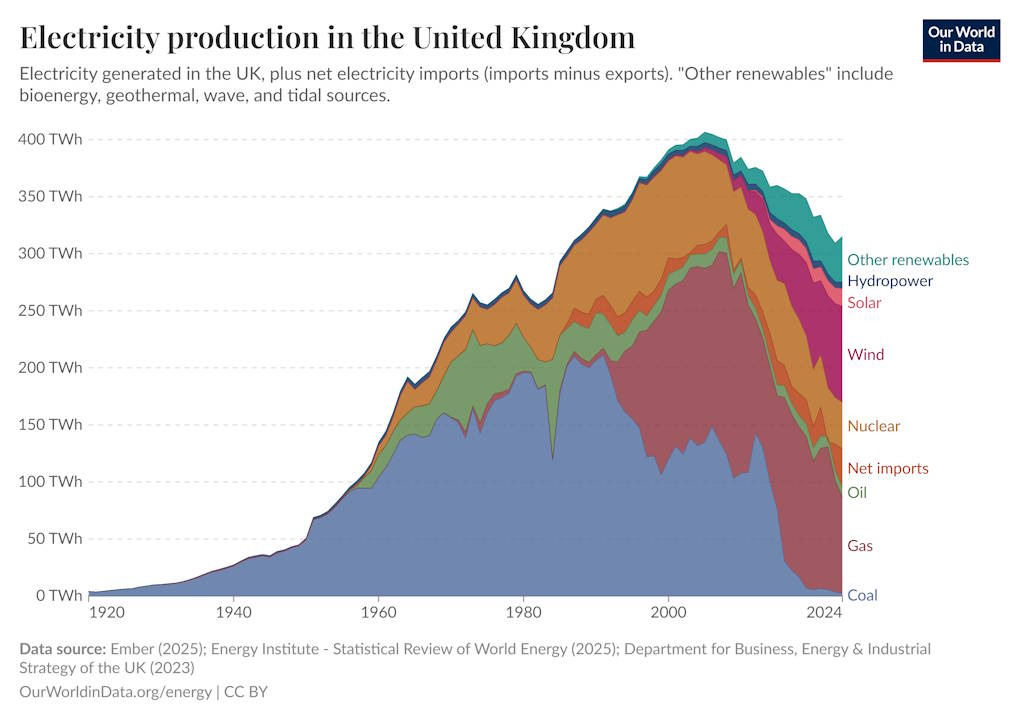

This happened because of a bunch of British government policies to restrict the use of fossil fuels and nuclear,1 in the name of promoting green energy. Coal was phased out completely, and gas and nuclear severely curbed, in order to make way for renewables that were very slow to ramp up:

But the UK, unlike most poor countries, is not very sunny. And it doesn’t have a lot of land for wind farms. The UK was one of those small special cases where it really did make sense to keep using fossil fuels and nuclear. The UK is a relatively small nation, so this wouldn’t have made much of a difference to climate change. But it’s also a nation dominated by environmentalism and degrowth-adjacent ideology, and so the decision was made to reduce the nation’s energy generation.

As The Economist reports, this has caused energy prices in the UK to skyrocket, immiserating the population:

British electricity prices have become expensive. For decades, those prices rarely strayed far from the rest of Europe’s. Now household bills are 20% above the average for the major European economies, and industrial bills 90% higher...The gap with America is starker yet…

Britain’s clean-power push has started to land on bills. Paying for the new pylons and wires that will stitch together a more complex grid where power is generated in pockets all over the country is driving up network costs. So are “balancing costs”, whereby generators are paid to smooth out the volatility of renewables…Since 2019 green subsidies and network costs…have contributed about two-thirds as much to the real-terms rise in bills as the wholesale price of electricity has…Both are set to keep rising…

High bills have squeezed Britons’ finances….Output of energy-guzzling goods like chemicals, plastics and metals has fallen by more than 20% since gas prices first spiked…Energy flows into everything, even the services that dominate Britain’s economy. References to energy costs in corporate reports and earnings calls have more than tripled since 2019, driven by the consumer, tech and financial sectors.

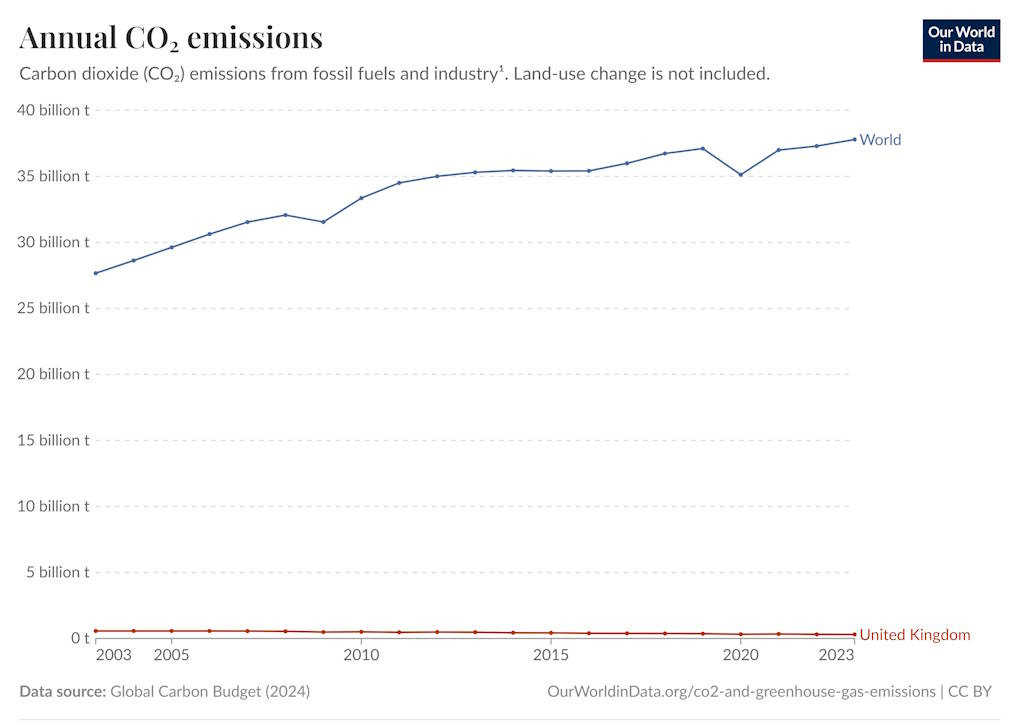

As the article notes, expensive energy is causing a political backlash in the UK. And why shouldn’t it? The UK chose to deprive its citizens and companies in order to produce a totally performative emissions reduction, setting an example that almost no other countries followed:

U.S. conservatives look across the pond at that failure, and they think “We can’t let that happen here.” They don’t understand that America is much sunnier than the UK and has a lot more land, and that green energy is therefore potentially much cheaper here than there. All they see is the clash of political movements and ideologies.

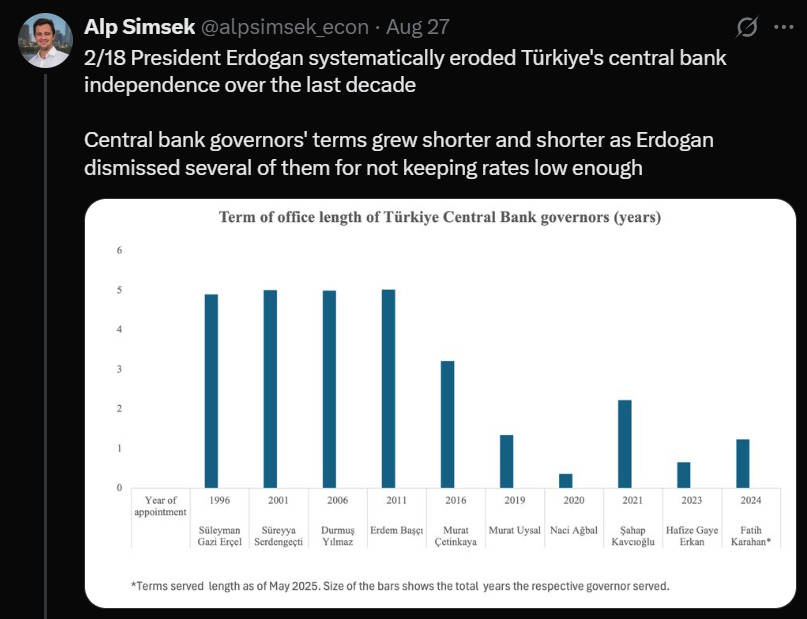

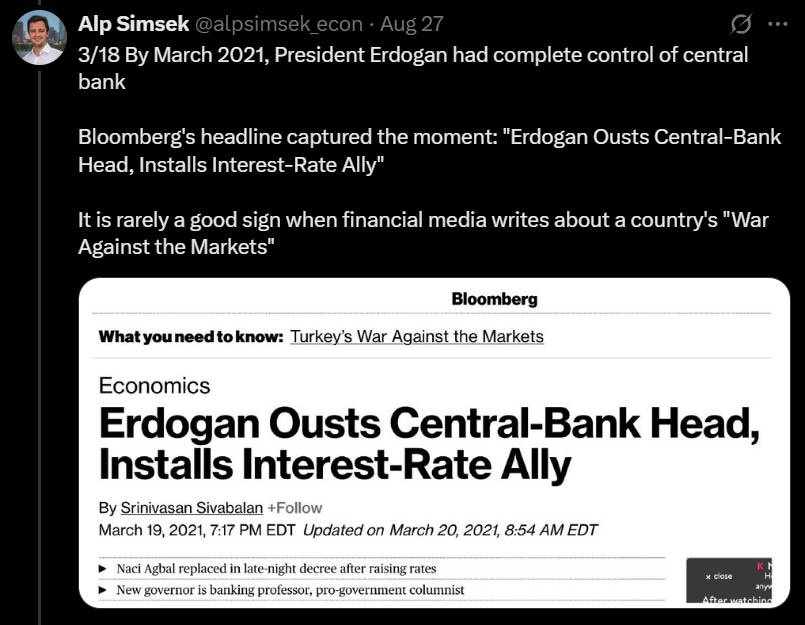

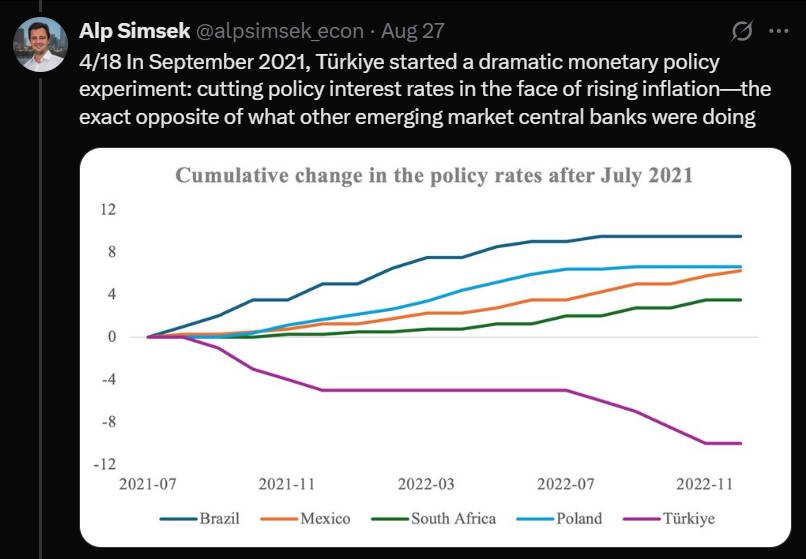

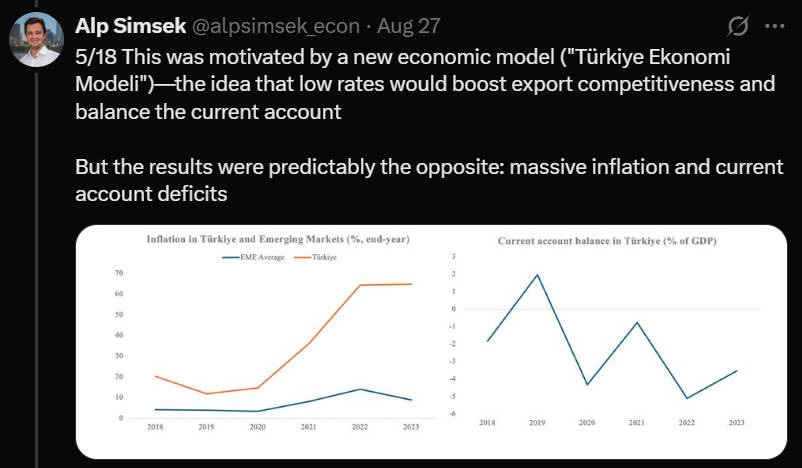

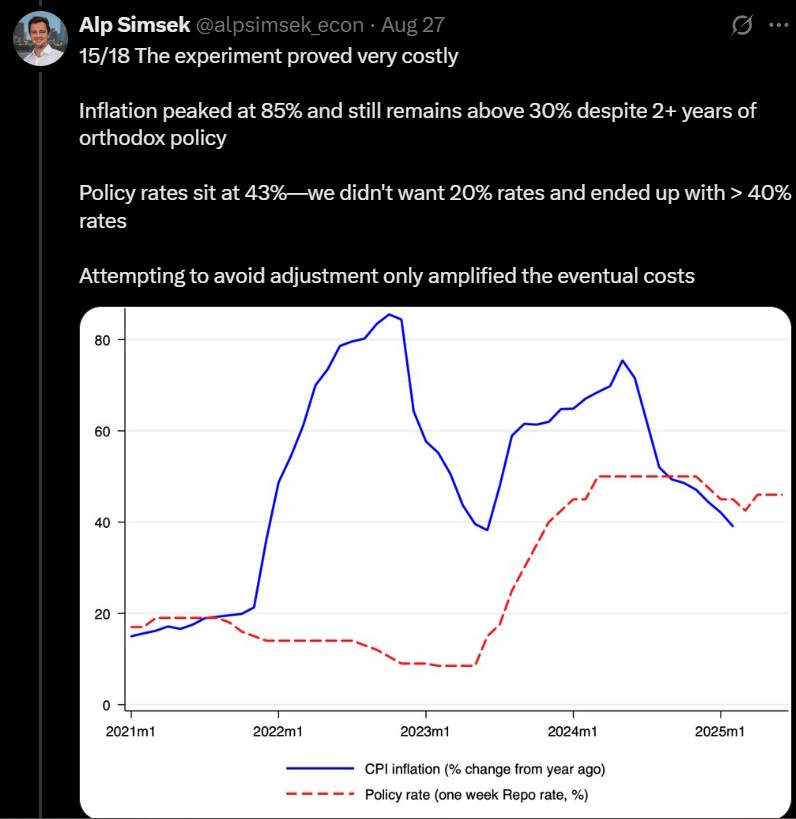

5. When Turkey tried getting rid of central bank independence

When Trump fired Fed governor Lisa Cook, it raised a lot of concerns about central bank independence. Although Stephen Miran, Trump’s nominee to replace Cook, says he will respect the Fed’s independence, this is only the latest in a long line of Trump’s attacks on the Fed. During a recent interview, JD Vance declared that the President, not the Fed, should have the power to determine monetary policy.

This is very bad, but it’s not always clear to regular folks why it’s bad. I wrote a post outlining some of the negative effects that the end of Fed independence could have on the U.S. economy. But an even simpler way to get the gist is to look at what happened to Turkey over the last few years.

Hakan Kara and Alp Simsek have a new paper explaining what happened when Turkey’s President Erdogan decided to take over monetary policy and force interest rates down. Simsek has a good thread telling the basic story. Here are a few excerpts from that thread:

I’ve long thought that of any modern leader, Trump seems most similar to Erdogan. We should pay attention to Turkey’s failed experiment, and avoid following a similar path.

6. Those terrible tariffs

In my debate with Oren Cass at the top of this post, Oren attacked the field of economics, declared that it isn’t a real science, and scoffed at predictions that tariffs would hurt the U.S. economy. Meanwhile, the economist Brian Albrecht wrote a post explaining some simple econ models showing the downsides of tariffs:

Here are some excerpts from Albrecht’s post:

Now let’s add the most important realistic feature, which I think is the most important…The economy at Home has “Climbers” who gather coconuts, but the economy in [the] Foreign [country] has “Weavers” who are skilled at making sturdy ladders. Ladders…are a productive input that allows a Climber to gather far more coconuts. Home imports these ladders from Foreign, paying for them with coconuts…

The government at Home, needing revenue, decides to place a tariff on imported ladders…The result harms the economy’s productivity. The tariff makes ladders (a key tool for production) more expensive. Faced with this higher cost, some Climbers decide it’s no longer worth it to buy a ladder and go back to climbing with their bare hands. Their productivity plummets. The entire production system at Home becomes less efficient…

Let’s extend our ladder example, but now think about what happens over time. Instead of each Climber just buying one ladder when they need it, imagine that ladders are durable and Climbers can accumulate them. The more ladders a Climber owns, the more productive they become…Home imports these ladders from Foreign and, over time, builds up a stock of them…

Now, suppose the government places a tariff on imported ladders. This doesn’t just affect the Climbers who want to buy a ladder today. It affects the entire process of capital accumulation in the economy…With the tariff making ladders more expensive, fewer new ladders get imported each year. The economy’s stock of ladders grows more slowly. Some old ladders break down or wear out, and they’re not replaced as quickly because of the higher cost. Over time, the entire economy becomes less productive as the capital stock shrinks relative to what it would have been.

They harm the economy’s ability to become more productive over time. A tariff on capital goods is like a tax on economic growth itself…The effects compound. With fewer ladders, workers are less productive. With lower productivity, the economy generates less income. With less income, there’s less money available to buy new ladders, even if the tariff were removed. The economy gets stuck in a lower-productivity equilibrium.

Who should we believe? Oren Cass’s bombastic pronouncements that economics isn’t a real science? Or Albrecht’s conceptual explanations of how supply chains and capital accumulation ought to work in a global economy?

Well, I don’t know. But here’s a news story about U.S. manufacturing activity:

US factory activity shrank in August for a sixth straight month, driven by a pullback in production that shows manufacturing remains bogged down by higher import duties…

“We continue to have weak demand overall, still due to tariff uncertainty,” Susan Spence, chair of the ISM’s Manufacturing Business Survey Committee, said on a call with reporters. [emphasis mine]

Hmm, perhaps a discipline doesn’t have to be a “science” in order to give you useful information about how the real world works…

Environmental movement types don’t think of as “green” even though it produces no carbon. This is, of course, very foolish, and it comes from ancient tribal political conflicts that almost no one remembers anymore.

Why does Noah keep blaming liberals for right wingers inability to see reality when it comes to green power generation instead of their willful ignorance?

"...but mostly it’s because the right thinks of renewable energy as being all about climate change, rather than about securing cheap reliable supplies of electric power. In one sense, you can’t blame the right for thinking like this. after all, climate change activists on the left pretty much only talk about solar and wind in terms of the carbon emissions they prevent..."

It's really incredibly insulting. People on the right are just as smart as anyone else. They have had access to the economic information on green energy if they want to look outside their info bubble. it's not hard. But they don't want to look. And right wing media won't tell them.

Blaming liberals, Noah says talk of greenhouse gas reductions.... "sets conservatives’ alarm bells ringing, because they think of climate change primarily as something that leftists play up in order to bring down capitalism and soak the rich."'

It's not the fault of the proponents of green energy that the right believes it's really all about the left wanting to end capitalism and soak the rich. That's the fault of right wing propaganda outfits like fox news that relentlessly blow a minority environmentalist view out of all proportion and turn it into the face of environmentalism.

The right wing media turns that molehill into a mountain, while ignoring or even lying about the economic superiority of green energy. And lying about the truth of climate change. But Noah ignores all that and continually blames liberals for making the right hate green energy.

He goes out of his way to make excuses for them...

Today, out of positive green energy outcomes that are literally everywhere in the world (lead by liberals), he cherry picks the example of the UK and their not as positive outcomes and says they are the boogeyman the right wing fears !

Like even one out of 10,000 Magas know anything about the UK's energy policies and prices. And as far as conservative leadership "looking across the pond", well , they should see 5 success stories for every UK. So if they really are pointing and saying "No" to green energy because this is where green energy gets us, they are cherry picking too.

It's a lot of willful ignorance that keeps right wing Americans hating solar and wind.

The right will, and does, turn against everything the left advocates regardless of how rational or not it is. That should be obvious by now. If the left had stressed the economic benefits more ( They did way more than Noah gives credit for) The right would still be against it. If not it would be an outlier.

Continually, cherry picking the "good" reasons for right's irrational knee jerk rejection of anything that smells of liberal, enables it. It justifies it. It turns them into the victims of liberals.

It's an effort to make them blameless for their own choices and actions.

"In one sense, you can’t blame the right for thinking like this"

No. You can blame them. And should blame them. They are intelligent enough adults that can't be excused for forming bad opinions about important matters based on their prejudices about liberals rather than easily obtainable facts and truth.

Providing some examples that support their prejudices doesn't get them off the hook.

I was surprised to hear that business majors had as much of an income premium as engineering majors, so I dug into the study you cited. The thing that surprised me is that science majors actually had just as much of an anti-premium as humanities majors! Social science majors were in the middle.

Interestingly, it looked like up until 1980, humanities, science, social science, and engineering were all pretty similar while business was way ahead. But then in the 1980s, engineering pulled ahead with business, while the others mostly stayed behind, until social sciences started rising.