At least five interesting things to start your week (#50)

Permitting reform; industrial policy progress; China stimulus/bailouts; men and politics; wokeness; tariffs; a bad union demand

Howdy, folks! It’s time for your quasi-regular, quasi-weekly Noahpinion roundup of interesting stuff from around the world. First, here’s me on Jim Pethokoukis’ podcast, talking about techno-optimism:

Jim is still one of the most criminally underrated bloggers out there.

I also have an episode of Econ 102, where I tell Erik about a book draft I’m writing for the Japanese market:

In fact, I’ve been working pretty hard on that draft this past month, even as I was also dealing with a nasty infection and attending several weddings. But I still promise to provide you with the high-quality, high-volume econ content that you crave.

Speaking of which, on to this week’s list of interesting things.

1. Progress on permitting reform, at last

Permitting reform is really important. Basically, anything you want to build — housing, factories, infrastructure, energy, you name it — needs to be built on land. And since the 1970s, America has implemented a byzantine system of land-use permitting restrictions that make it very hard to build anything at all. NEPA and similar state laws, which allow pretty much anyone to sue developers to force them to complete years of onerous paperwork, even if their projects are already fully compliant with all environmental laws, are a big part of this problem. As Zachary Liscow puts it in a recent review paper, “in the US, permitting is slow, infrastructure is expensive, and environmental outcomes are not particularly good.”

Although some progressives defend NEPA, America’s permitting regime is especially pernicious to the progressive goal of having the state take a more active role in the economy. As Matt Yglesias argues eloquently in a recent post, America’s onerous permitting regime hurts state capacity even more than it hurts the private sector, since government involvement triggers rules like NEPA.

Permitting requirements can also hurt national security — America is having trouble weaning itself off of Chinese critical mineral supplies in part because new domestic mines are being held up in court by NEPA.

Fortunately, permitting reform is very popular, polling at +15 to +25, with support across the political spectrum. And it’s also probably very effective — for example, Germany has had good success accelerating renewable energy construction by reforming its own permitting process:

In Germany, securing approvals for one 2022 project to erect three wind turbines required 36,000 pages of documentation printed out and handed to the authorities…Since then, German red tape has been drastically reduced…In just over two years, the country is now deploying more renewables than any other European peer…The government attacked the problem in a systematic way and anchored the solutions in legislation…One law designated clean-energy projects an “overriding public interest” that serves national security….Further amendments cut the number of environmental assessments required to just one and simplified the previous double-tracked grid-planning process by removing an entire agency’s involvement.

For the past four years, the U.S. government has been deadlocked on permitting reform, with various vested interests and ideological actors blocking every deal that reformers propose. But fortunately, after four long tortuous years, the government is finally starting to move.

Most importantly, Congress just passed a bill — which Biden has pledged to sign — that exempts many CHIPS Act projects from NEPA. Gary Winslett has a good explainer of what the bill does:

[F]ederal [CHIPS Act] subsidies…no longer, by themselves, make these fabs “a major federal action” and so don’t require the NEPA review…[I]f, for some other reason, a fab receiving federal money does fall under NEPA, the Department of Commerce gets to be the lead agency in the NEPA review. That should help speed things up…

The bill also expands the use of categorical exclusions in semiconductor production. That should help expedite the environmental review process for semiconductor projects by exempting certain activities from more extensive NEPA review requirements.

Progressives tried hard to stop this bill, but couldn’t get a third of the House to oppose it. Good.

The House also passed a NEPA exemption for geothermal energy, and a bill streamlining NEPA for forest fire prevention efforts. Biden will probably support the former, but unfortunately still opposes the latter. And there still hasn’t been a breakthrough on permitting reform for green energy and transmission, which is holding back Biden’s green industrial policy. But the gathering pace of permitting reform bills is an excellent sign in any case.

And in a very encouraging sign, Kamala Harris might be an even bigger advocate of permitting reform than Biden has been:

In general, I think, younger Democrats seem to understand the importance of building things, while older ones are a little more likely to be mentally stuck in the 1970s era when development was seen as something that automatically hurts the environment. So as generational turnover proceeds, I expect to see the Dems warm even more to permitting reform.

Anyway, this is a really important and good trend, and I hope it’s just the beginning.

2. The Build-Something Country?

U.S. economic policy has been shifting toward industrial policy. A number of commentators who oppose this shift have been quick to seize on any sign of problems as a reason to dismiss the whole enterprise. For example, in March of this year, Matt Cole and Chris Nicholson wrote an op-ed in The Hill with the bombastic title “DEI killed the CHIPS Act”. Their single piece of evidence for this bold thesis was that TSMC’s fab in Arizona was projected to have significant delays due to a dispute with local construction unions.

In fact, even before that dismissive op-ed came out, the labor dispute it referenced had already been solved. And just a month after the op-ed came out, TSMC was officially allocated its CHIPS Act money, and suddenly declared that its Arizona project was now ahead of schedule.

Now, less than six months later, Tim Culpan reports that TSMC’s Arizona plant has started making some chips for Apple. The chip they’re making is fairly advanced, and they’re reportedly getting good yields:

Apple’s A16 SoC, which first debuted two years ago in the iPhone 14 Pro, is currently being manufactured at…TSMC’s Fab 21 in Arizona in small, but significant, numbers…Volume will ramp up considerably when the second stage of the…fab is completed and production is underway, putting the Arizona project on track to hit its target for production in the first-half of 2025…“The Arizona project is proceeding as planned with good progress,” Nina Kao, a spokeswoman for TSMC told me…

This is a BFD. TSMC Arizona is the marquee project of the US government’s $39 billion CHIPS for America Fund under the CHIPS Act…The fact that they went for the most-advanced chip they could manage on US soil, in terms of both technology and volume, shows Apple and TSMC want to start big…

Currently TSMC is achieving yields in Arizona that are slightly behind what’s enjoyed back home in Taiwan (basically, neck and neck). Most important, though, is that improvements are moving so rapidly that true yield parity between Taiwan and Arizona is expected to be reached in coming months.

Everyone who leaped at the chance to declare the CHIPS Act a failure at the first report of delays now has egg on their face.

Meanwhile, Biden’s other big piece of industrial policy legislation — the Inflation Reduction Act — appears to be giving U.S. solar manufacturing a big boost. Solar manufacturers are ramping up production, and the U.S. is getting the ability to build the pieces of the solar supply chain that it had previously outsourced entirely to China and other countries:

This is still small potatoes compared to what China can make, but it means that if a war breaks out, U.S. deployment of solar power won’t be cut off.

Note that both the successes in chips and solar are cases where the private sector made most of the investment itself, and the U.S. government simply prompted that investment with subsidies. This stands in stark contrast to cases where the U.S. government promised to build things itself, and was stymied by its lack of state capacity and its own byzantine permitting process.

A big lesson here is that Matt Yglesias is right, and the U.S. government has willfully destroyed much of its state capacity since the 1970s. Therefore, the most effective industrial policy, at least right now, is for government to act as the spur for the private sector to invest its own money.

The even bigger lesson, though, is that industrial policy’s knee-jerk naysayers need to be a little more circumspect and judicious, or else they’ll keep looking silly when industrial policy succeeds. There are certainly problems and challenges and drawbacks associated with industrial policy, and we need smart, thoughtful critics who can identify those. People who simply pounce on any whiff of difficulty are unhelpful.

3. China wakes up to macroeconomic reality

Two weeks ago I argued that China is suffering from a shortage of aggregate demand, and that the solution is to have the central government A) bail out banks and local government financing vehicles, and B) use fiscal and monetary stimulus:

Perhaps Xi Jinping reads my blog.1 China is unleashing some more substantial stimulus measures:

The People’s Bank of China led the charge to revive sentiment on Tuesday in a rare televised press briefing beamed live around the world, opening its war chest to stock markets and making money cheaper to borrow….The next day it kept the positive news flowing by lowering the interest rate on its one-year loans to lenders by the most on record, while the government issued rare cash handouts and floated new subsidies for some jobless graduates…

The 24-man Politburo led by Xi followed that on Thursday with more pro-growth goodies, vowing to boost fiscal spending and making its first pledge to stop property prices “declining.” It also unveiled a new focus on boosting consumption, saying it was “necessary to respond to the concerns of the masses.”…The barrage of policy announcements marked a sea change in Xi’s approach to managing China’s $18 trillion economy, after proudly resisting big stimulus for so long.

Chinese stocks immediately soared.

Even more encouragingly (at least, if you want China to keep growing), Xi’s government looks like it might bail out the Chinese banking system:

China is considering injecting up to 1 trillion yuan ($142 billion) of capital into its biggest state banks to increase their capacity to support the struggling economy…The funding will mainly come from the issuance of new special sovereign bonds…The details have yet to be finalized and are subject to change, the people added. Such a move would be the first time since the global financial crisis in 2008 that Beijing has injected capital into its big banks.

For the uninitiated, “injecting capital” means “giving banks money”. It means a bailout.

This is probably even more important than stimulus, since getting banks lending again is the key to a sustained recovery. China boosters have long held that Chinese banks’ bad debts don’t matter, because banks and the state are one and the same — this is called the “unitary state” theory. That theory is probably wrong. Chinese banks have their own incentives, and fear getting culled by the government if they fail. Injecting them with capital helps them gain the confidence to lend again, because it gives them a cushion against failure.

The final step in this process would be to bail out China’s local government financing vehicles, which have become incredibly important to China’s regional economies. But just bailing out the banks and doing some major fiscal and monetary stimulus should have a big effect in terms of shortening and ameliorating China’s recession.

4. The possibly nonexistent gender wars

In the 2010s, Americans taught themselves a whole bunch of unhelpful tropes about politics that must now be unlearned. Many of those tropes were about identity politics — for example, the idea that conservative values must be an expression of white supremacy, misogyny, and other sorts of in-group supremacism.

I always considered this a rather impoverished mode of analysis. It captures something about some parts of American politics, but even in those limited cases it’s only one of many things that’s going on.

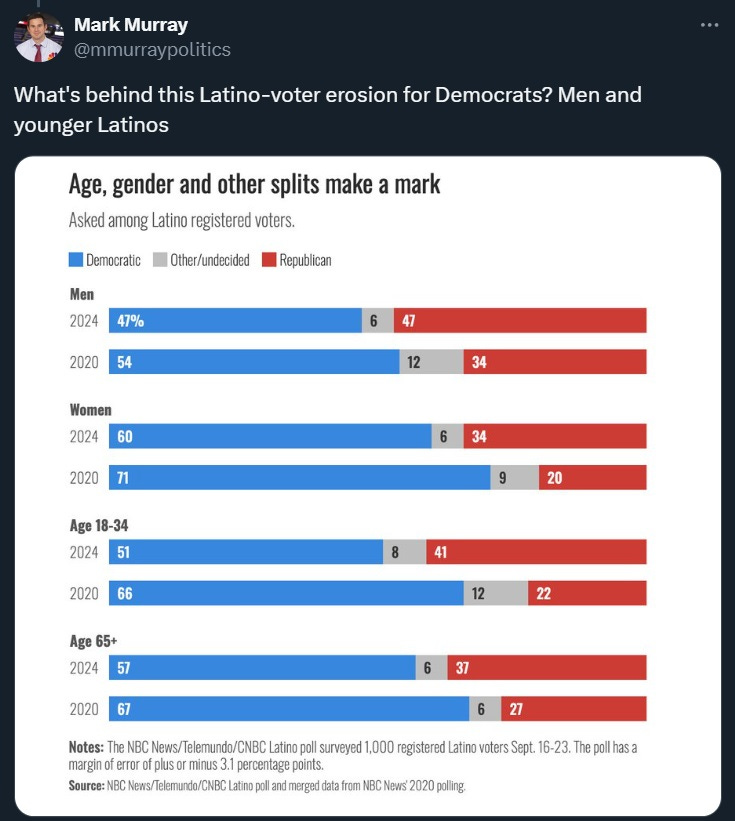

For example, take the by-now-well-documented shift of Hispanic voters toward the Republican party over the past few election cycles. That shift appears to be continuing apace. After 2020, some progressives tried to claim that the shift was because Hispanics were “white-adjacent”. More recently, I’ve been seeing the claim that it’s mostly Hispanic men driving the shift, and that it’s a reflection of gender polarization in politics:

But as Musa al-Gharbi and Matt Yglesias both pointed out, this data clearly shows that Hispanic women have shifted more to the GOP than Hispanic men, even if Hispanic men are still more Republican in an absolute sense. People want to spin a narrative about gender polarization, but in fact Hispanics seem to be getting a little less polarized by gender. Exit polls from 2020 tell a similar story.

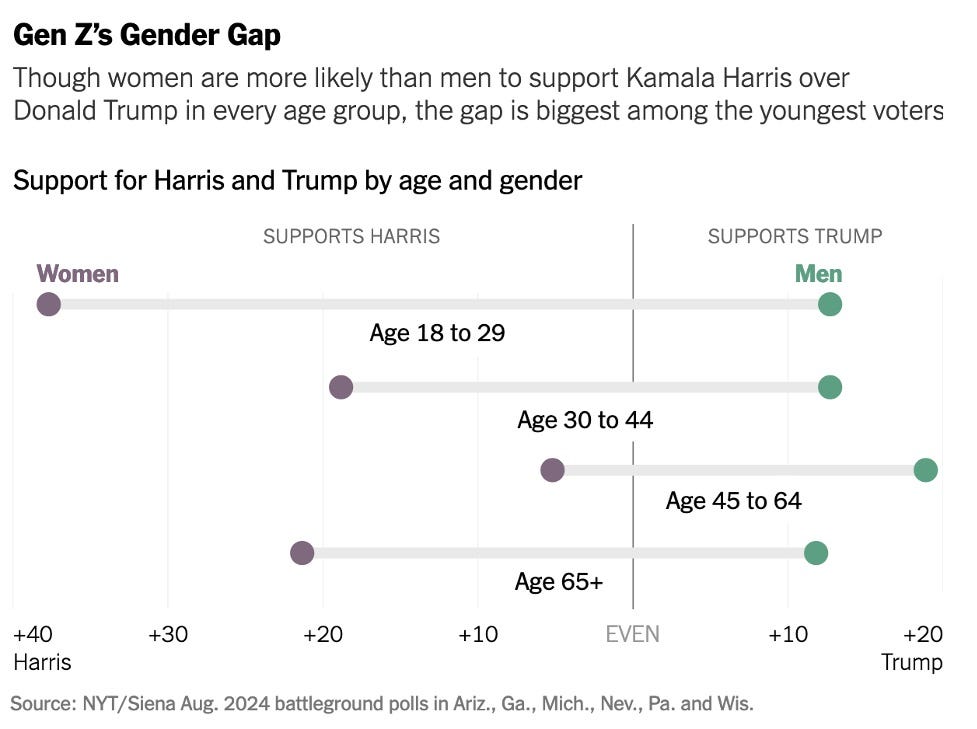

In fact, a lot of people are trying to tell a grand story about gender polarization in American politics. For example, the New York Times published a story in August citing data showing a huge gender gap between Trump and Harris support among young people:

And Derek Thompson, one of my favorite writers, penned a long and thoughtful post speculating about why young people might be more split along gender lines.

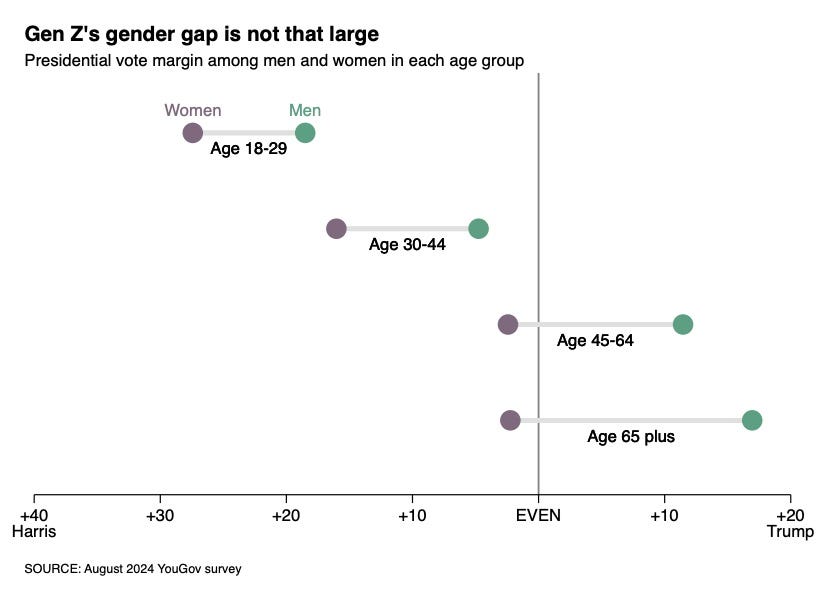

The problem is, the trend might not really exist. John Sides, who has done polling work on this topic, points out that in his own surveys for YouGov this year, the younger generation looks less polarized by gender than the older generation:

And he notes that in a Pew poll from this year, the gender gap for age 18-29 looks moderate — a little bigger than for the Millennials and gen Xers, but much smaller than for the Boomers. An NBC poll was somewhere in the middle.

Thompson also acknowledges the possibility that the gender gap is a data artifact, and points to a post by Rose Horowitch. Horowitch writes:

The Gen Z war of the sexes, in other words, is probably not apocalyptic. It may not even exist at all…[I]f young men and women really were drifting apart politically, you would expect to see evidence on Election Day. And here’s where the theory starts showing cracks. The Cooperative Election Study…found that nearly 68 percent of 18-to-29-year-old men voted for Joe Biden in the 2020 presidential election, compared with about 70 percent of women in that age group—the same percentage gap as in 2008. (The split was larger—nearly seven points—in 2016, when Trump’s personal behavior toward women was especially salient.) Catalist, a progressive firm that models election results based on voter-file data, found that the gender divide was roughly the same for all age groups in recent elections. In the 2022 midterms, according to Pew’s analysis of validated voters, considered the gold standard of postelection polling, the youngest voters had the smallest gender divide, and overwhelmingly supported Democrats.

There may ultimately turn out to be a political gender gap, but the data we have at this point don’t seem to justify the commentariat’s general enthusiasm for gender-based theories of American politics. I think people are seeing too much of what they want to see, and that the simplistic identity-based rules that Americans learned to use in the 2010s are actually not that good at describing political reality.

I think what we need here is to rediscover old modes of analysis — seeing politics through the lens of economic interests and cultural values, instead of simply as a conflict between identity blocs fighting over social supremacy.

5. Wokeness recedes

“The conservatism of a religion — its orthodoxy — is the inert coagulum of a once highly reactive sap.” — Eric Hoffer

As long as we’re on the topic of 2010s identity politics, let’s talk about wokeness. Back in 2021-22 I wrote a series of posts about this sociocultural phenomenon, which I summarized here:

My basic thesis is that wokeness is a Protestant-derived American belief system and social phenomenon that has been around since before the founding of the United States, and that it periodically resurfaces for a while when technological and economic changes allow. And my basic prediction is that after the efflorescence of the 2010s, wokeness will recede into a waxy orthodoxy, governing a shrinking set of university administrations and school boards and online communities, until it reemerges on the scene many decades from now.

Last year, Musa al-Gharbi wrote a great post in which he pulled various data sources to show that the “Great Awokening” of the 2010s is receding. Now The Economist has a similar post, with different data sources. Here are a few excerpts:

[D]iscussion and espousal of woke views peaked in America in the early 2020s and have declined markedly since…Almost everywhere we looked a similar trend emerged: wokeness grew sharply in 2015, as Donald Trump appeared on the political scene, continued to spread during the subsequent efflorescence of #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, peaked in 2021-22 and has been declining ever since…

In the most recent Gallup data, from earlier this year, 35% of people said they worried “a great deal” about race relations, down from a peak of 48% in 2021 but up from 17% in 2014…In [General Social Survey] data the view that discrimination is the main reason for differences in outcomes between races peaked in 2021 and fell…in 2022. Some of the biggest leaps and subsequent declines in woke thinking have been among young people and those on the left…

The share of Americans who consider sexism a very or moderately big problem peaked at 70% in 2018…The share believing that women face obstacles that make it hard to get ahead peaked in 2019, at 57%…Pew finds that the share of people who believe someone can be a different sex from the one of their birth has fallen steadily since 2017, when it first asked the question. Opposition to trans students playing in sports teams that match their chosen gender rather than their biological sex has grown from 53% in 2022 to 61% in 2024, according to YouGov…

[T]he term “white privilege”…in 2020…featured roughly 2.5 times for every million words in the New York Times, but by 2023 had fallen to just 0.4 mentions for every million words…Mentions of woke words in television peaked in 2021…

Mentions of DEI in earnings calls shot up almost five-fold between the first and third quarters of 2020…They peaked in the second quarter of 2021…They have since begun to drop sharply again…The number of people employed in DEI has fallen in the past few years.

This fits with my predictions from 2021. And if I’m right, this trend will continue over the next few years, even as conservatives continue to find and highlight examples of wokeness in media, academia, and other progressive parts of American culture. Wokeness is an orthodoxy now, and orthodoxies aren’t fun and cool anymore. But wokeness is very optimized for being a charismatic activist movement, and not very optimized for being a conservative set of rules and traditions. So I expect its decline to be swift…until, of course, it bursts forth once again. But that will be when you and I are very old or dead.

6. Tariff justifications

The U.S. government is becoming more hostile to Chinese imports all the time. Biden recently announced that he’ll limit the “de minimis” exemption that allows Chinese companies like Temu and Shein to ship Americans small cheap packages without paying tariffs. And Biden’s administration is considering an outright ban on Chinese components in any cars that are connected to the internet, to protect against possible sabotage.

Meanwhile, Trump is going around promising tariffs, tariffs, and more tariffs as the solution to a variety of economic ills (or just because he really likes tariffs). While this is far from the most important policy issue in the election, some people are talking about it.

For example, the economist Kim Clausing argues that instead of tariffs, the U.S. should reduce the incentive for offshoring by cracking down on tax havens. But I think that while this is a laudable move, it wouldn’t really do much vis-a-vis China, because China is not a tax haven. Clausing’s proposal really misses the reason that Democrats have been embracing tariffs on China, which is national security.

Oren Cass, meanwhile, has a post at the Atlantic making a general case for tariffs as a useful policy tool. Some excerpts:

[Economists’] first mistake is to consider only the costs of tariffs, and not the benefits...Tariffs address [an] externality…[D]omestic production has value beyond what market prices reflect…To the extent that tariffs combat those harms, they accordingly bring collective benefits…

As the fallout from globalization has illustrated, manufacturing does matter. It matters for national security, ensuring both the resilience of supply chains and the capacity of the defense-industrial base. It also matters for growth…

Manufacturing drives innovation. As the McKinsey Global Institute has noted, the manufacturing sector plays an outsize role in private research spending. When manufacturing heads offshore, entire supply chains and engineering know-how follow. The tight feedback loop between design and production, necessary to improvements in both, favors firms and workers positioned near the factory floor and near competitors, suppliers, and customers.

Cass also argues that the harms from tariffs will be limited when foreign companies circumvent the tariffs by building their products in the U.S. And he points out that tariffs do raise tax revenue.

These are all reasonable arguments, and you’ll find me saying similar things when I defend industrial policy. But there are two questions here that Cass doesn’t really address.

First, even though I think Cass has mostly identified real externalities, that doesn’t mean tariffs are the most effective policy tool to address those externalities. Tariffs’ effects are limited by exchange rate adjustment — when you put tariffs on China, the yuan gets cheaper, partially negating the effect of the tariff. Also, tariffs on intermediate goods actually exacerbate many of the externalities Cass talks about, by blocking domestic manufacturers from getting affordable inputs for their production processes. That may be a cost worth paying, for national security reasons, but it is a real cost.

And second, Cass’ general defense of tariffs ignores many of the real, specifc features of Trump’s tariff proposals. Trump would slap tariffs on U.S. allies — this would decrease national security rather than enhance it, because it would limit the markets available to companies on both sides, preventing them from achieving economies of scale. It would also hamper both sides’ defense-industrial bases.

So on both sides of the tariff debate, I still see too much debate about ideal policies, and not enough engagement with the specific policies being enacted or proposed. That said, I think the debate is MUCH improved from where it was just a few years ago, so that’s good. Articles like Clausing’s and Cass’ are making reasonable arguments instead of shouting ideological positions, and I always want to see more of that.

7. Unions shouldn’t fight automation

It’s very hard to be a pro-union pundit when unions make demands like this one:

Determined to thwart the automating of their jobs, about 45,000 dockworkers along the U.S. East and Gulf Coasts are threatening to strike on Oct. 1, a move that would shut down ports that handle about half the nation’s cargo from ships…The International Longshoremen’s Union is demanding significantly higher wages and a total ban on the automation of cranes, gates and container movements that are used in the loading or loading of freight at 36 U.S. ports…

A prolonged strike would almost certainly hurt the U.S. economy. Even a brief strike would cause disruptions…

[Union president] Daggett said the union members expect to be waging their biggest fight — against the automation of job functions at ports — well into the future.

“We do not believe that robotics should take over a human being’s job,” he said. “Especially a human being that’s historically performed that job.”…

Experts say it’s not altogether clear whether automation would lead to layoffs…A 2022 study by the Economic Roundtable of Los Angeles that was funded by the West Coast dockworkers union found that automation cost 572 jobs each year in 2020 and 2021 at partially automated terminals at the ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles…But another study that same year by a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, that was commissioned by port operators and shippers concluded that between 2015, when Los Angeles-area ports adopted some automation, and 2021, paid hours for port union members grew 11.2%.

At the huge Port of Rotterdam, one of the world’s most automated ports, union workers pushed for early-retirement packages and work-time reductions as a means to preserve jobs. And in the end, mechanization didn’t cause significant job losses, a researcher from Erasmus University in the Netherlands found.

U.S. ports trail their counterparts in Asia and Europe in the use of automation. Analysts note that most U.S. ports take longer to unload container ships than do those in Asia and Europe and suggest that without more automation, they could become even less competitive.

Banning automation is just a way of killing the goose that lays the golden eggs, ultimately hurting dockworkers. Meanwhile, it acts as a tax on the whole U.S. economy. If you didn’t like the inflation of 2021, you should want more efficient, high-capacity automated ports. The U.S. should emulate Rotterdam instead of retreating into self-defeating luddism.

Hahahahahahahahaha no.

My mind is blown by unions demanding no automation, the USA ports are already a joke. As is our shipbuilding industry...

I want to observe with detached amusement (and sadness) that we actually confronted and tried to address some major problems in our society over the past few years, including some instances of really hideous police brutality that have no place in a modern society. We also learned that Hollywood covered for Harvey Weinstein for years, and that our law enforcement system had chosen to give Jeffrey Epstein the lightest possible slap on the wrist while harassing his victims. (The guy responsible for the Epstein non-prosecution actually got rewarded with a cabinet position for his trouble.)

I won't say that we made *no* progress on these issues, but in the end our response was some pretty weak-tea bullshit. Yet to read this post, all that was just an annoying trend, like beanie babies or Chappell Roan, and we should all be glad it's over. Maybe in the moment this seems like a reasonable conclusion, but I'm not convinced that future generations will think very highly of us for it.