Tariffs are coming

A global trade war looms. But tariffs are not necessarily the best weapon for that war.

A trade war is probably coming to a planet near you. Tariffs are inevitably going to be one of the main weapons used to fight this trade war, so it’s important to understand what tariffs do and don’t accomplish.

One spark that could ignite the fire of global trade war is Donald Trump. Trump is currently leading in most presidential polls, and he’s promising to enact far bigger and more sweeping tariffs than he did in his last term — a 60% tariff on Chinese goods, and a 10% tariff on all imported goods from all countries. The latter move would almost certainly provoke retaliation from countries across the globe.

But there’s an even more important reason we’re facing a global trade war, and that’s China’s response to its economic slowdown.

China is using an export glut to fight an economic slowdown

The property industry, which made up over a quarter of China’s economy, has basically collapsed, taking much of the country’s domestic demand down with it. In that sort of environment, one obvious move is to try to pump up export manufacturing.

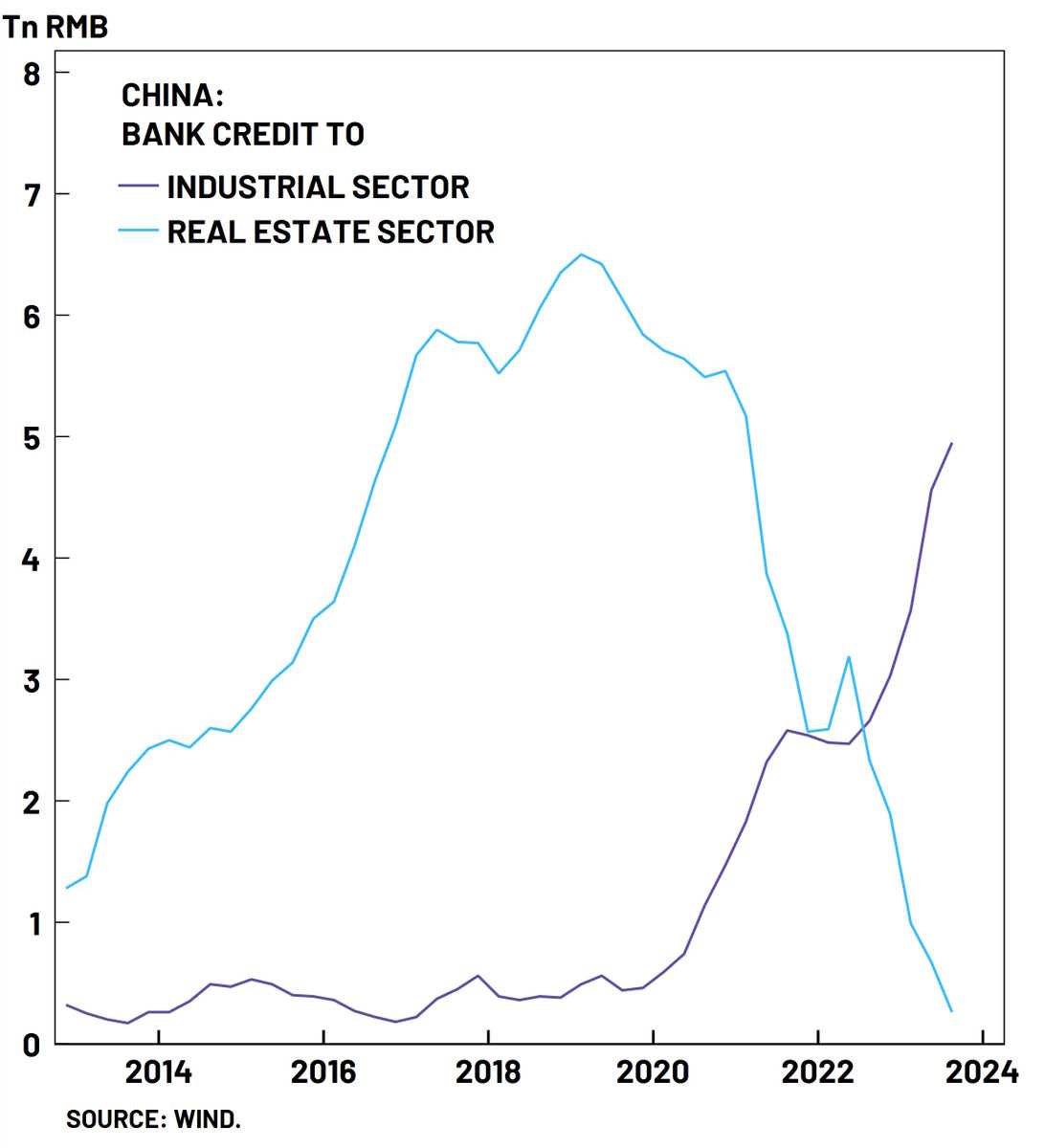

Just glancing at where Chinese banks are making their loans makes it clear that this is exactly what China is doing:

China’s government is making this happen by dishing out massive subsidies and cheap loans to favored export-oriented manufacturing sectors, and ordering companies in those sectors to produce more:

[China’s leaders] are obsessed with lithium-ion batteries, electric cars and solar panels. These sorts of technologies will, Xi Jinping has proclaimed, become “pillars of the economy”. He is spending big to ensure this happens…

Mr Xi’s manufacturing obsession is explained by the need to offset China’s property slump…[O]fficials now hope that manufacturing can pick up the slack. State-owned banks—corporate China’s main source of financing—are funnelling cash to industrial firms.[E]xporters in powerhouse provinces have been told to expand production. During the first 11 months of 2023 capital spending on smelting metals, manufacturing vehicles and making electrical equipment rose by 10%, 18% and 34%, respectively, compared with the same period in 2022…

[T]he country’s steel giants produced more metal even as the property industry suffered.Steel mills, which have access to cheap capital, are willing to take considerable losses in order to preserve market share.

It’s not just EVs, batteries, and solar panels, though. Chris Miller points out that although China’s leading-edge chipmakers are being hurt by export controls, it’s trailing-edge chipmakers are expanding production massively, and selling much of it overseas:

[It] may defy business logic but, helped by generous subsidies, China’s chipmakers are ramping up production capacity despite concerns about oversupply. According to one consultancy, the country’s chip production capacity will grow by 60 per cent in the next three years, and could double over the next five. Since western restrictions on the exports of chipmaking equipment to China mean that it can’t produce the most advanced processor chips, much of this production will be of foundational processor chips, which are widely used in cars, household goods and consumer devices.

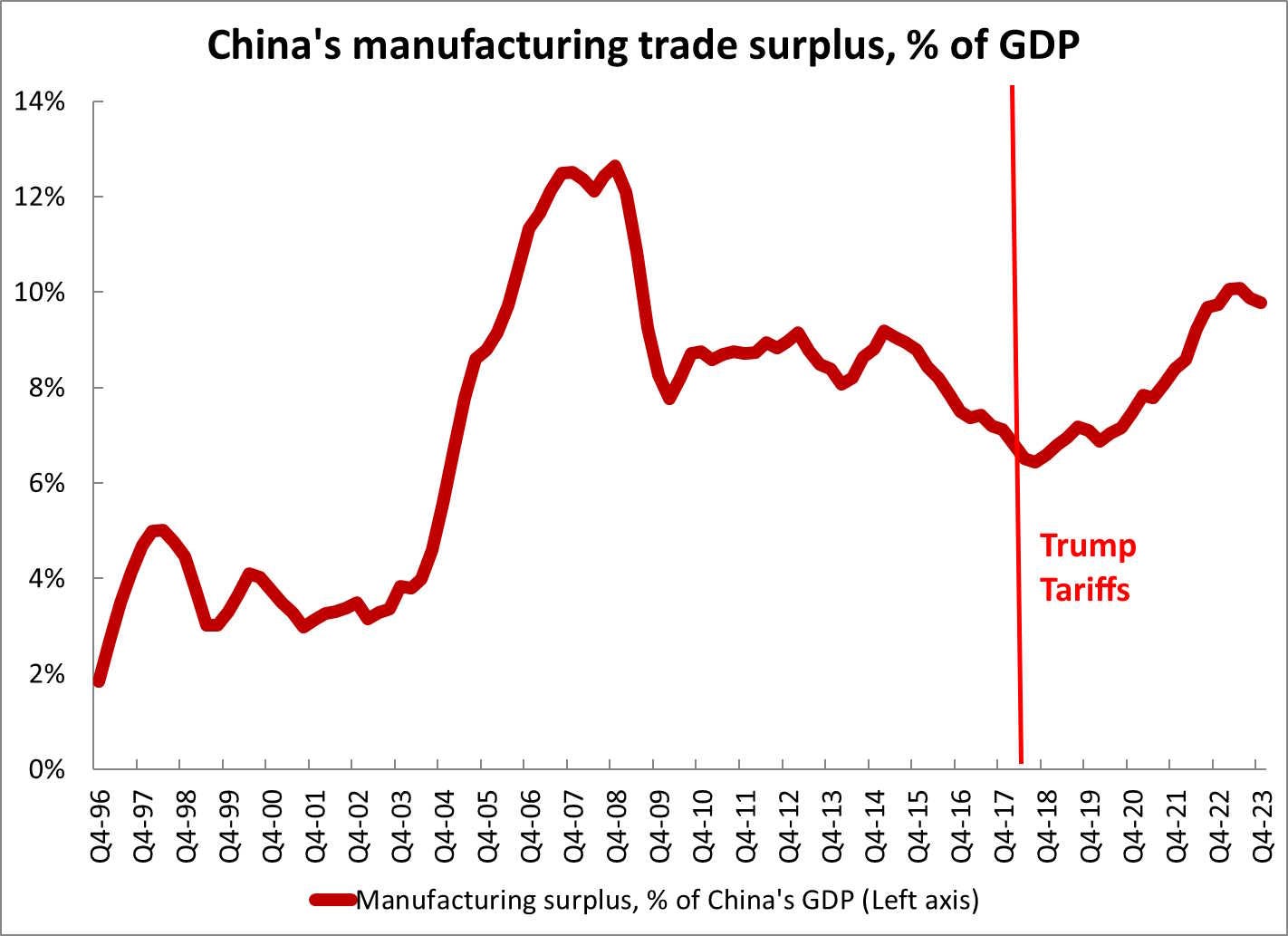

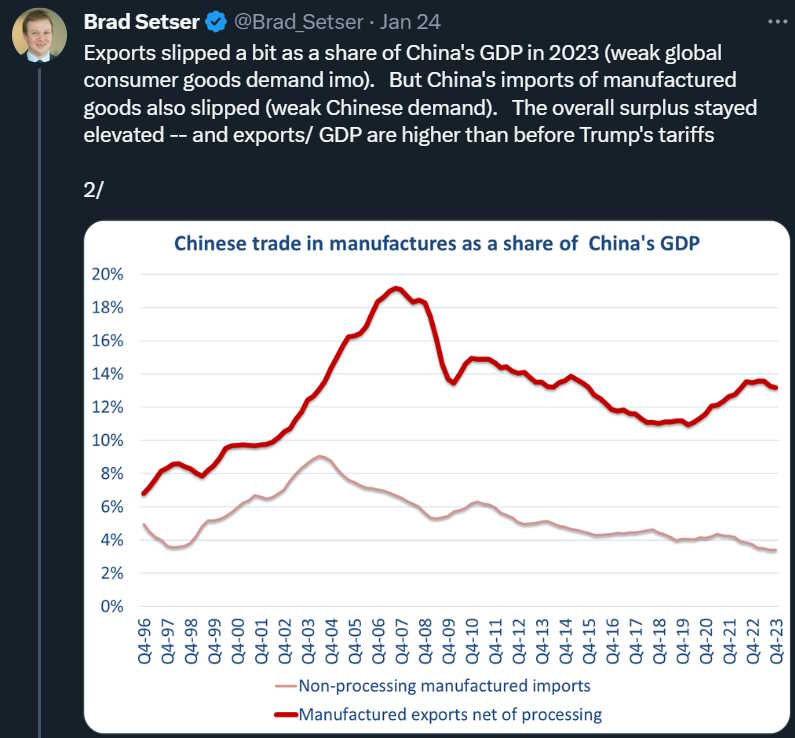

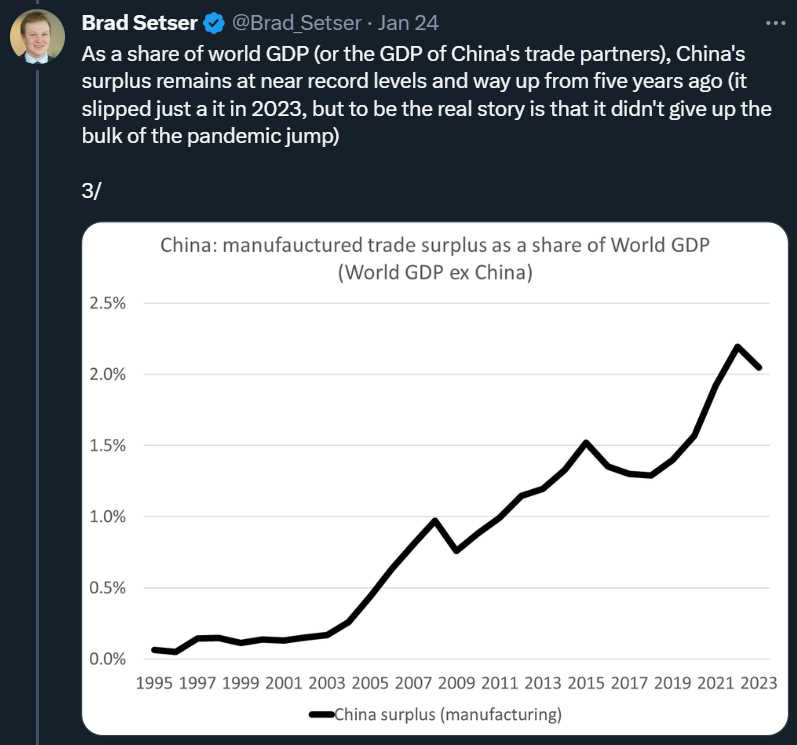

The problem is that thanks to the real estate bust, Chinese consumers aren’t really in a mood to consume much. That means that all the extra cars and batteries and chips and steel that the Chinese government is pushing companies to manufacture will be dumped on the global market for very low prices. Brad Setser, the most dogged and perspicacious observer of Chinese trade imbalances, has a good thread showing that this is already happening. Here are a couple of key charts from that thread:

Whether or not this technically constitutes “dumping”, it’s clear that China’s subsidies have reduced the price of Chinese export goods well below what an un-distorted market would bear.

Of course, everyone around the world knows that China is doing this, and they’re afraid that competition from the flood of ultra-cheap Chinese exports will decimate their own domestic manufacturing industries. I already wrote about this in the context of the European auto industry:

But a move toward tariffs to counter China’s export glut could be much broader than that, and could be swiftly followed by Chinese retaliation:

In November Britain launched a probe into Chinese excavators, after JCB, a local firm, alleged that Chinese rivals were flooding the market with cut-price machines. The EU is conducting an anti-subsidy probe into Chinese electric vehicles and an anti-dumping probe into Chinese biodiesel. The Biden administration has asked the EU to tax Chinese goods, offering to drop American tariffs on European steel in return. On January 5th China decided to hit Europe where it hurts, announcing an anti-dumping investigation into brandy…In September India imposed fresh anti-dumping duties on Chinese steel; in December it introduced new duties on industrial laser machines. Indeed, almost all the anti-dumping investigations that India’s trade authorities are now conducting concern China…In December the [Mexican] government announced an 80% tariff on some imports of Chinese steel.

In the U.S., meanwhile, the Chamber of Commerce is issuing warnings about dangers from Chinese overcapacity. Even Elon Musk, who has some of his own EV factories in China, is sounding the alarm:

Competition from Chinese EV makers may be starting to get to Elon Musk and Tesla. After a long battle for market share in China, Tesla’s CEO issued a warning to his fellow automakers: On a level playing field, Chinese carmakers will outcompete almost everyone else.

“Our observation is generally that Chinese car companies are the most competitive car companies in the world,” Musk said Wednesday, during Tesla’s earnings call. “If there are no trade barriers established, they will pretty much demolish most other car companies in the world,” he continued.

When even Musk wants trade barriers, there just isn’t much of a constituency for free trade left.

So even if Trump doesn’t get elected this November, a wave of tariffs is probably about to sweep across much of the world. The next questions are:

How effective would tariffs be in stemming the tide of Chinese imports?

Who will be hurt by tariffs?

Fortunately, thanks to Trump’s tariffs, we now have some recent experience to help us answer both of those questions.

Why tariffs are weaker than people think

First, let’s talk a little about the theory of tariffs. There are a number of theoretical reasons why taxing imports from another country will have a more limited impact than you might expect.

For one thing, tariffs are not applied on a value-added basis. If China makes a car and sells it to someone in Germany, a German tariff on Chinese goods will tax that car. If China makes a steering wheel and sells it to a Volkswagen factory in Germany, a German tariff on Chinese goods will tax that steering wheel. But if China makes a steering wheel and sells it to a Volkswagen factory in Turkey, who then sells the car to someone in Germany, a German tariff on Chinese goods won’t tax that steering wheel at all. It’ll slip right through the tariffs.

This will limit the effects of tariffs. In fact, when Trump put tariffs on China, we saw some Chinese producers simply sell their goods to Vietnamese middlemen, who slapped a “made in Vietnam” sticker on the goods and resold them to America, avoiding Trump’s tariffs completely. This is called “transshipment”, and countries try hard to crack down on it.

More realistically, Chinese companies will respond to tariffs by selling intermediate goods to assemblers in “third countries” that are not subject to tariffs. In fact, some pundits have argued that this behavior is so widespread that it means that trade decoupling between China and the U.S. hasn’t happened at all. Those pundits are wrong; there has been some trade decoupling. But they’re correct that intermediate goods sales to third countries reduce the effect of trade barriers. This is especially true of semiconductors, as Chris Miller points out; computer chips are by their nature an intermediate good, and China tends to sell a lot of them to assemblers in developing countries.

The second reason tariffs are weaker than people think is exchange rate adjustment. Economics is full of a whole bunch of little stabilizing mechanisms that partially cancel out the effect of any change. This is one of them.

In order to buy Chinese-made goods, you need Chinese currency — the RMB, also called the yuan. So if tariffs reduce demand for Chinese-made goods, there will be less demand for yuan. This will reduce the price of yuan — in other words, China’s exchange rate will depreciate. That will make Chinese goods cheaper on the world market. This will partially (though not completely) cushion the blow from tariffs.

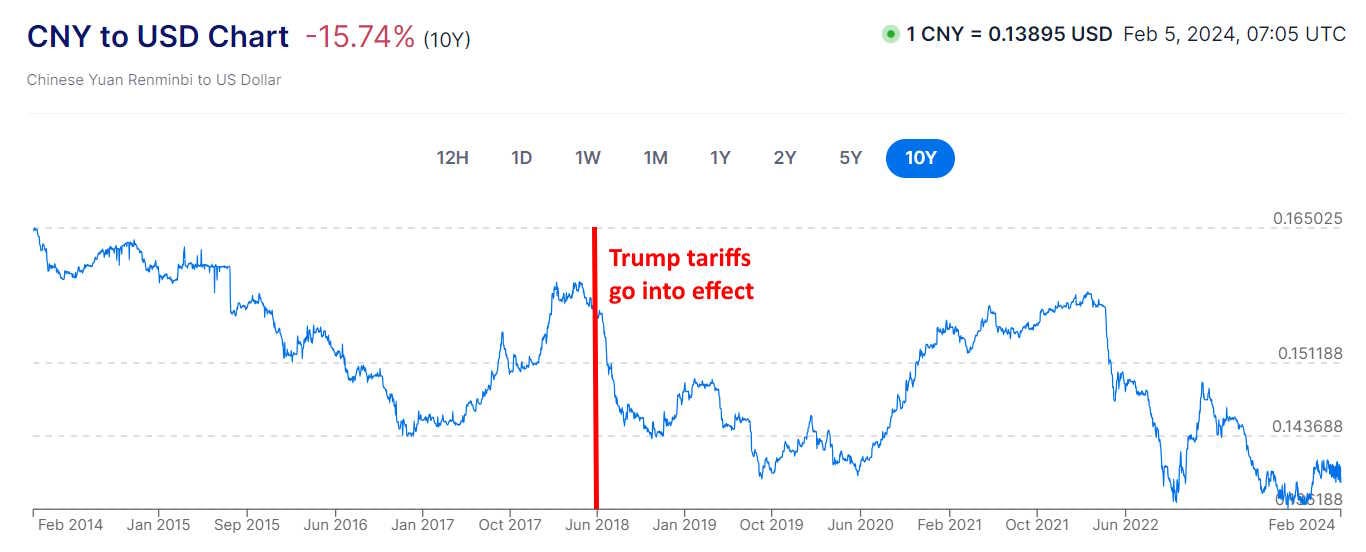

Let’s look at a graph of the yuan’s exchange rate against the dollar:

As you can see, the yuan got a lot weaker after Trump’s tariffs went into effect. This almost certainly cancelled out some of the effect that the tariffs would otherwise have had, by making Chinese exports more competitive. A 2020 paper by Jeanne and Son, which looks at the impact of tariff-related news on short-term exchange rate movements, argues that Trump’s tariffs were responsible for about two-thirds of the yuan’s drop in 2018-19.

The third reason tariffs tend to be weak tools is that tariffs on intermediate goods hurt domestic producers of finished goods. Suppose that U.S. automakers use a lot of Chinese-made batteries and steel because these are rally cheap. Now if you put a tax on imports of Chinese batteries and steel, you raise costs for U.S. automakers. That makes Ford and GM and Tesla less competitive in global markets — or even in the U.S. market — against Chinese rivals.

In fact, there’s a famous theoretical result in economics that says you shouldn’t tax intermediate inputs at all, which means they’re a particularly bad target for tariffs. But politicians rarely pay attention to famous theoretical results in economics, especially politicians like Trump. That’s why the first imports he went after with tariffs were steel and aluminum — two things that are usually used as intermediate inputs. And since China sells the U.S. a lot of intermediate industrial inputs, the China tariffs were also the type of thing that could be expected to raise U.S. manufacturers’ costs.

And, surprising exactly no one in the econ world, this is exactly what happened. Handley, Kamal, and Monarch (2020) found that Trump’s tariffs tended to make U.S. export manufacturing less competitive:

We examine the impacts of the 2018-2019 U.S. import tariff increases on U.S. export growth through the lens of supply chain linkages. Using 2016 confidential firm-trade linked data, we identify firms that eventually faced tariff increases…We construct product-level measures of exporters' exposure to import tariff increases and estimate the impact on U.S. export growth. The most exposed products had relatively lower export growth in 2018-2019, with larger effects in 2019. The decline in export growth in 2019Q3, for example, is equivalent to an ad valorem tariff on U.S. exports of 2% for the typical product and up to 4% for products with higher than average exposure.

In other words, by taxing foreign imports of intermediate goods, Trump also taxed U.S. exports. This was one reason why tariffs visibly failed to revive U.S. manufacturing during Trump’s term in office:

So anyway, there are a bunch of reasons why tariffs — especially of the type implemented by the Trump administration — are pretty weak as policy instruments go. And when we look at who bore the harm from Trump’s tariffs, we see that their impact wasn’t particularly big.

Trump’s tariffs hurt American consumers, American producers, and Chinese producers

Stephen Miller, a Trump apparatchik who’s best known for his harsh policies towards immigrants, recently defended tariffs as a way to tax foreign producers instead of American ones:

But as every economist and econ writer knows — and as the Community Notes swiftly reminded Miller — who pays a tax on paper is very different from who pays it in reality. The true financial burden of any tax depends on the elasticities of supply and demand.

And in the case of Trump’s tariffs, demand for imports was pretty inelastic — rich American consumers were willing to pay more for Chinese goods, and so they did end up paying more. Pretty much every study that looked into the tariffs found that the main financial burden fell on U.S. consumers.

But to be fair to Trump and Miller, this burden was actually really small. When you look at some of these studies, you see the impact of the tariffs being something like $17 billion or $51 billion a year. For an economy of $23,320 billion, those numbers are drops in the bucket. And over time, we can expect those numbers to get even smaller, as consumers shift away from Chinese producers.

So yes, the tariffs hurt American consumers, but the harm was pretty minuscule. A little more significant was the harm to American manufacturers, as detailed above. As for American workers, the tariffs did absolutely nothing at all. Here’s Autor et al. (2024):

We study the economic and political consequences of the 2018-2019 trade war between the United States, China and other US trade partners at the detailed geographic level, exploiting measures of local exposure to US import tariffs, foreign retaliatory tariffs, and US compensation programs. The trade-war has not to date provided economic help to the US heartland: import tariffs on foreign goods neither raised nor lowered US employment in newly-protected sectors[.]

So Trump’s tariffs did a little bit of damage and didn’t really help any major sector of the economy.

But what about the effect on China? If you think of tariffs primarily as a way to help domestic producers and workers, Trump’s tariffs were a total disappointment. But if you think of tariffs as a weapon, with the goal of weakening a rival nation’s economy, then perhaps a tiny bit of harm to your own citizens’ pocketbooks can be regarded as an inevitable casualty of war.

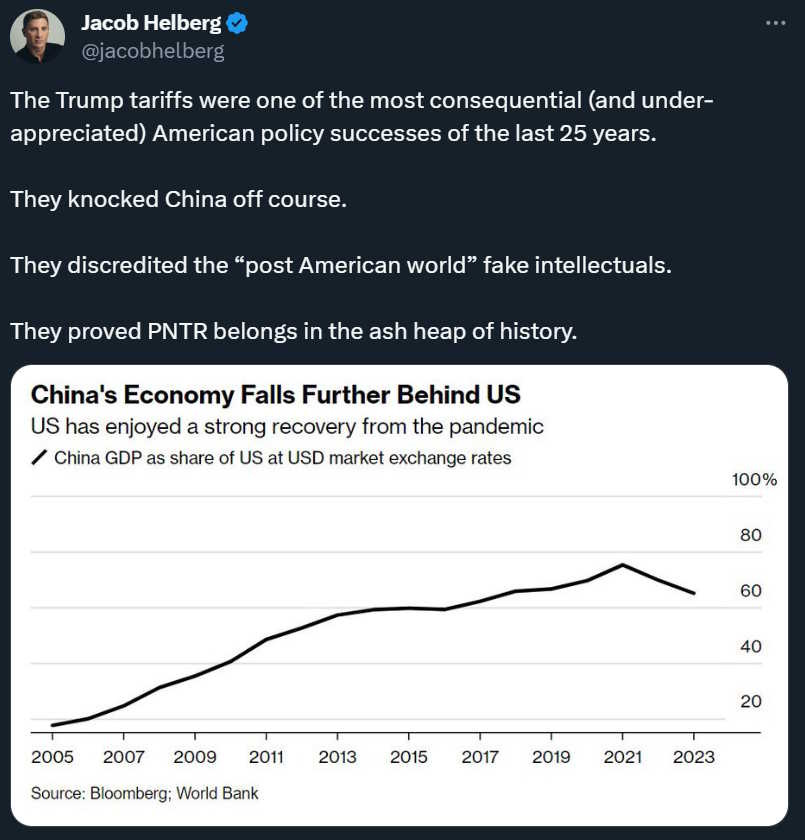

Some people certainly do think that Trump’s tariffs did huge damage to China’s economy:

This is vastly overstated. First of all, the chart that Helberg shows is a ratio of GDP at market exchange rates — China’s sharp decline relative to the U.S. in 2022-23 comes almost entirely from a massive depreciation of its currency. That depreciation reflected underlying economic weakness, but in practice it doesn’t make China actually poorer — it mainly just makes China’s exports more competitive. So people should stop using this chart as proof that China is falling behind the U.S.

Second, Trump’s tariffs didn’t derail China’s manufacturing exports at all! In fact, China’s trade surplus in manufactured goods rose after the tariffs went into effect:

The fact is, China’s growth was already slowing well before Trump’s tariffs, due to a productivity slowdown and a fall in the return to capital. The tariffs did not change China’s trajectory, nor did they cause the shift toward real estate that ultimately brought China’s rapid growth to a halt.

But it is true that Trump’s tariffs hurt China, at least a bit. The key paper here is Chor and Li (2021), who looked at nighttime lighting — a measure of economic activity that’s difficult to fake — and concluded that a small number of provinces that were hit hardest by the tariffs took a modest but significant economic hit:

How much has the US-China tariff war impacted economic outcomes in China? We address this question using high-frequency night lights data, together with measures of the trade exposure of fine grid locations constructed from Chinese firms' geo-coordinates…[W]e find that each 1 percentage point increase in exposure to the US tariffs was associated with a 0.59% reduction in night-time luminosity. We combine these with structural elasticities that relate night lights to economic outcomes…The negative impact of the tariff war was highly skewed across locations: While grids with negligible direct exposure to the US tariffs accounted for up to 70% of China's population, we infer that the 2.5% of the population in grids with the largest US tariff shocks saw a 2.52% (1.62%) decrease in income per capita (manufacturing employment) relative to unaffected grids. By contrast, we do not find significant effects from China's retaliatory tariffs.

Overall, they find a 0.28% decrease in income per capita for all of China. That’s only slightly higher than the 0.07%-0.22% of GDP that American consumers paid. And of course, this negative impact was also very transitory.

In other words, Trump’s tariffs did very, very little. The attention they received was due to the attitude shift that they represented — the end of an era of free trade and the beginning of an era of strategic competition among nations. But as an actual policy tool for affecting trade flows or boosting domestic industry, they were pretty much a nothingburger.

Alternative tools for trade wars

The general weakness and unimpressive track record of tariffs over the past few years shows why all the countries now warily eyeing China’s great export flood should try to develop alternative policy tools. Chris Miller, ahead of the curve as usual, lists some promising alternative ideas for the chip sector:

Given the administrative complexity of tariffs, officials are exploring alternatives. One approach is to subsidise the use of non-Chinese chips, though this would require governments to find new funds.

A second option is to limit the market access of specific Chinese companies…Finally, Chinese chips could simply be banned from “critical” use cases.

Similar approaches could be used for Chinese batteries and steel.

There are also various non-tariff barriers that countries can use to block imports without tariffs. For example, Turkey is using onerous regulatory requirements to block Chinese EV imports:

Companies importing EVs to Turkey must have at least 140 authorized service stations spread evenly across the country and open a call center for each brand, according to a Trade Ministry decree published last month.

The onerous requirement is widely seen as targeting Chinese vehicles. Imports from the EU and countries that have free-trade agreements with Turkey are exempt from the decree. Importers have only until the end of the month to comply, a next-to-impossible task for many.

A final approach would be quantity restrictions — actually banning imports of certain goods beyond a certain threshold.

Countries should, of course, think very hard about their objectives before applying any of these tools. Restrictions on intermediate goods might be necessary for national security reasons, but they come at the cost of hurting domestic producers — barriers against final goods like EVs are much safer. And when possible, trade barriers that are aimed at a specific country should try to take supply chains into account — if you’re trying to tax Chinese goods, then a Vietnamese phone whose components are 70% Chinese should absolutely get taxed.

But in any case, a global trade war is brewing. Arguments that countries should go back to embracing free trade, so that their consumers can have slightly cheaper goods, are likely to fall on deaf ears. The best thing we can do now is to try to make sure that whatever trade barriers countries do throw up are consistent with their objectives, and have as few self-destructive side effects as possible.

Before discussing the effectiveness of various tools, we need to ask, "effective for what?" What is the problem we want to solve? Take EVs. What do, should we want?

Great, informative article. Thank you.

Do you think there's a possibility that Trump would tax and thereby punish American companies that do business in China? Not sure how such a tax would be structured or enforced, but it could be sold politically as aiding and abetting our enemy. To be clear, I think such a policy sounds unwise, even dangerous.