In which British writers scold America on trade

If you don't acknowledge the point of tariffs, how can you hope to criticize them?

As I wrote in my post about Biden’s tariffs last week, protectionism is now a bipartisan consensus in America; you cannot find a major party or political faction that is not fully on board with the idea of taxing Chinese-made goods. And as I wrote in my weekly roundup, this is likely to put pressure on other countries to follow suit, because U.S. tariffs will focus the huge wave of Chinese exports on an even smaller set of countries. Protectionism is thus likely to become the world’s new default approach to trade, at least as far as China is concerned.

Not everyone is happy about this, of course. In particular, a number of prominent British publications have been issuing full-throated denunciations of the protectionist turn. For example, here’s The Economist arguing that various trade policy interventions, from sanctions to industrial policy, will inevitably hurt the world’s poor:

This unhappy regression—call it deglobalisation, for want of a better term—is beginning to become visible in the economic data…

[T]he world’s governments are imposing trade sanctions more than four times as often as they did in the 1990s…Governments are also screening foreign investments more carefully and often barring investments in “strategic” companies…The second big change is the rise of industrial policy. Politicians are frantically competing to build up domestic supply chains and local industries…in clean energy, electric vehicles and computer chips…

Not only has global trade in goods stagnated; the same problem now afflicts services, too. Cross-border investment is in retreat, as well, as a share of global GDP. Both long-term (direct) and short-term (portfolio) flows are well below their peaks. Companies are retrenching, to avoid geopolitical rifts in particular…

The reduced efficiency that this entails does not seem to bother the many politicians who are embracing deglobalisation…The golden age of globalisation caused an unprecedented decline in global poverty…Moving away from global integration thus presents a massive risk to the world’s poor, in particular.

The article acknowledges that these harms haven’t manifested yet — the world economy is still growing at about the same pace it was 10 or 20 years ago. And the article also acknowledges the possibility that poor countries like India will grow faster due to friendshoring. But it sticks stubbornly to the assertion that eventually, the global poor will be the ones to suffer.

And here’s Ed Luce in the Financial Times, arguing that tariffs will hurt consumers, slow the transition to green energy, and exacerbate tensions with China:

America’s direction of travel is ominous. At one speed or another, Republicans and Democrats alike are now in favour of pulling up the global drawbridge…As Biden knew in 2019 but appears to have forgotten, the costs of tariffs are borne by consumers not by importers…For the symbolic gain of a handful of muscular jobs, Biden is imposing a broad tax on the middle class and undermining US competitiveness…

Then there is the hit to his climate change policy. The cost of all forms of renewable energy has nosedived in the last decade, chiefly because of China…The Biden effect will be to raise the US domestic price of EVs, solar panels and other green inputs and delay America’s energy transition…[Then there] are the uncounted national security costs of deglobalisation. The last time the world was confronted with rising populism was in the 1930s. America’s initial response was to make it worse. The 1930 Smoot-Hawley Act raised US tariff barriers and triggered beggar-thy-neighbour protectionism elsewhere. This time, again, America’s instinct is to disengage: Trump across all fronts, including military alliances; Biden only on the economic front.

Another Economist article makes similar arguments. And an FT editorial makes them yet again. A third Economist piece tells us that we really just need to remember the wisdom of David Ricardo from Econ 101:

Return, for a moment, to first principles. As David Ricardo laid out more than two centuries ago and experience has since shown, it makes sense for governments to open their borders to imports even when others throw up barriers. Residents in the liberalising country enjoy lower prices and greater variety, while companies focus on what they are best at producing. By contrast, tariffs coddle inefficient firms and harm consumers…

America learned this the hard way in the 1980s, when Japanese carmakers—in Washington’s crosshairs—agreed to quotas, driving up their prices in America. And for what? The “big three” carmakers continued to churn out clunkers. Today’s American firms fear competition from BYD’s Seagull, some versions of which cost less than $10,000 in China. Now, they can sell inferior cars for three times the price.

And so on, and so forth. Tariffs, folks: Is there any calamity they can’t cause?

The truth is, I’m sympathetic to many of these arguments. Managed poorly, the new system of trade barriers really could leave many poor countries bereft of investment and markets for their exports, slowing their growth. American consumers definitely will pay a price for not being able to buy Chinese EVs (though they were never going to sell for $10,000 in the U.S.; that was a flight of fancy on the part of the Economist writer). Taxes on cheap Chinese solar panels, batteries, and EVs really will slow the green transition, if only modestly. And some American companies probably will become complacent due to a lack of competitive pressure.

Under a Trump administration, the consequences could be even worse. In his first term, Trump was in the habit of slapping tariffs on U.S. friends and allies, like Canada, Europe, Mexico, and Japan. This practice would fragment U.S. alliances and prevent the emergence of a democratic trading bloc that could rival China’s immense size.

So I definitely acknowledge the costs and risks of tariffs. And yet I feel that in their rush to condemn Biden’s new policy, the British writers have made an incomplete and weak case. In particular, they have failed to grapple with the main reason that tariffs — not to mention other new policies like export controls, industrial policy, and sanctions — are being deployed.

The primary reason for all of these policies is national defense. Yes, political considerations like protecting the auto industry and catering to populist sentiment certainly play a role. But the most important motivation for the tariffs and other interventionist policies — the reason that so many U.S. elites embraced the new policies with so little pushback — was the military threat that China represents.

Without manufacturing industries, it is very hard to fight an industrial war. Fine wine, management consulting, and overpriced eldercare may command high prices in peacetime, but when bombs are dropping on your city, they will not offer a means of fighting back. If the U.S. and its allies find themselves without substantial manufacturing industries during a war with China, the result could be far more dire than higher consumer prices or slower adoption of EVs.

A world ruled from Beijing and Moscow is unlikely to value the economic rules and institutions that the writers of the Economist and the Financial Times hold so dear. Instead, a world where the power of the U.S. and other democracies have been smashed is likely to be a dirigiste one, where global trade is arranged primarily for the benefits of strongmen like Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin. Such strongmen are unlikely to listen to British pundits lecturing them about David Ricardo. In fact, they are unlikely to listen to British pundits about much of anything. (As far as I know, Russians and Chinese people generally lack the peculiar American reverence for anything uttered in a British accent.)

Every single one of the Biden administration policies that the Economist and FT writers revile — the tariffs, the subsidies, the export controls, and so on — is aimed at making sure the U.S. does not lose critical manufacturing industries that it would need in order to mount a defense against China and Russia. We do not know — at least, I do not know — if they will be effective in this task. But this is undoubtedly their core purpose and reason for existence.

Export controls are intended to stop China from dominating high-end semiconductors — the most strategic of all industries. Investment restrictions are intended to prevent China from appropriating America’s remaining technological secrets and handing them to its own military-industrial complex. Tariffs and industrial policy are intended to prevent America from deindustrializing in the face of Chinese competition. It’s all about national defense.

And yet the British writers basically never acknowledge this at all. Only Luce mentions potential national security benefits from Biden’s policies, and only in passing, and only regarding chip export controls. Otherwise, crickets. When the Economist declares that “first principles” prove that “it makes sense” for the U.S. to engage in unilateral trade liberalization with respect to China, the “principles” and the “sense” are purely economic, with zero mention or consideration of the benefit of a strong national defense.

I know David Ricardo’s theory well; I have taught it to undergraduates. Regardless of whether it’s a good theory of the gains from trade, it does not contain any provision whatsoever for national security. There are things that matter in the real world that Econ 101 simply doesn’t tell you how to deal with. And yet we must deal with them all the same.

How can you intelligently criticize a policy if you don’t even acknowledge its purpose? You cannot. What better alternative policy for national security do these British writers suggest? They suggest none. We do not know if they still hew to the 1990s-era American belief that economic engagement would pacify China (though Luce sort of hints at this idea), or the 2010s-era German belief that buying Russian gas would pacify Putin. We do not know if they have some alternative suggestion for promoting manufacturing without engaging in industrial policy or trade barriers.

We do not know these things because they did not feel the need to tell us. They decided that simply listing the costs and risks of Biden’s policies, and waving in the direction of Econ 101 theory, would be sufficient to make their case.

Because it does not address the reasons our leaders enacted these policies in the first place, Americans are highly unlikely to listen to Economist and FT writers’ advice to scrap them — our reverence for British accents notwithstanding. But I should probably mention that another reason we’re unlikely to take this advice is that we can see the cautionary tale of Britain itself.

During the heyday of the British Empire’s victories over France in the 1700s and early 1800s, manufacturing was a relatively minor part of military might. Armies were bought rather than built, and so a strong tax system and a strong finance industry were the key to winning wars in that era. Britain was better at these things than France, and so it triumphed. Meanwhile, trade with its far-flung colonies enriched Britain. This wasn’t exactly free trade, given the fact that colonies were captive markets and their industrial specializations were largely dictated from London, but the pro-trade rhetoric of the time seems to have given British intellectuals an enduring attachment to the idea.

But when the 20th century came along, Britain was presented with a very different sort of foe. Germany promoted its heavy manufacturing industries quite heavily, and Britain’s withered under a combination of foreign competition and lack of investment. This worked out to Britain’s disadvantage in World War 2, in which Britain’s defense-industrial base was unable to keep pace with the Nazi war machine.1 Only by allying with the world’s two premier manufacturing powers was the UK able to fend off the German menace, and even then its empire was fatally weakened.

Fast forward to the present day, and Britain’s long-term neglect of manufacturing still seems to be holding it back. As Brad DeLong and Stephen Cohen wrote in Concrete Economics, a “lack” of industrial policy actually ends up being a pro-finance industrial policy. And so it has gone with Britain, whose relentless NIMBYism, low R&D spending, and general aversion to industrial policy caused it to lose export competitiveness in manufacturing industries, but which still managed to thrive economically as the financial center of the European Union.

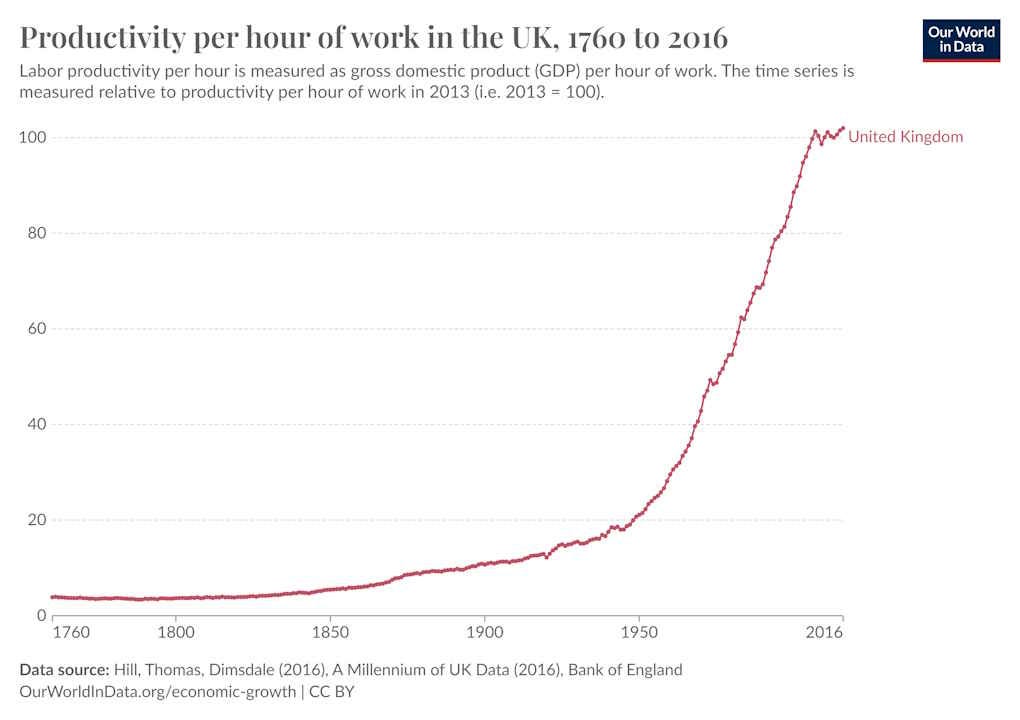

Even without the outbreak of war, this model demonstrated distinct weaknesses. The financial crisis of the late 2000s caused UK productivity to abruptly flatline after centuries of steady growth:

This graph ends before Brexit; the stalling of UK productivity and living standards was not due to sudden deglobalization. It was due to the fact that a modern economy of any significant size needs high-value industries other than finance in order to prosper.

But it’s in the security realm that the UK has suffered most. With its military having shrunken steadily over the years, Britain now depends even more on the U.S. for its safety from the resurgent Russian threat. Its lack of manufacturing capacity means that it would have difficulty finding assembly lines to convert to defense production in case Putin or one of his successors ever made it to Britain’s doorstep.

And now British pundits want America to walk down that same road? When Britain deindustrialized, it could rely on America’s mighty factories for its defense; if and when American deindustrializes, what protector can we turn to? There is none. The advocates of dogmatic, Econ 101-style unilateral free trade have no plan.

Fortunately, Americans are unlikely to listen. Much as with degrowth, we are likely to reject unilateral free trade as just another quaint, misguided idea from across the pond. Whether the kind of policies we’re now using can actually succeed at preserving and improving our manufacturing industries is still a very open question. But simply giving up doesn’t feel like a viable option.

Update

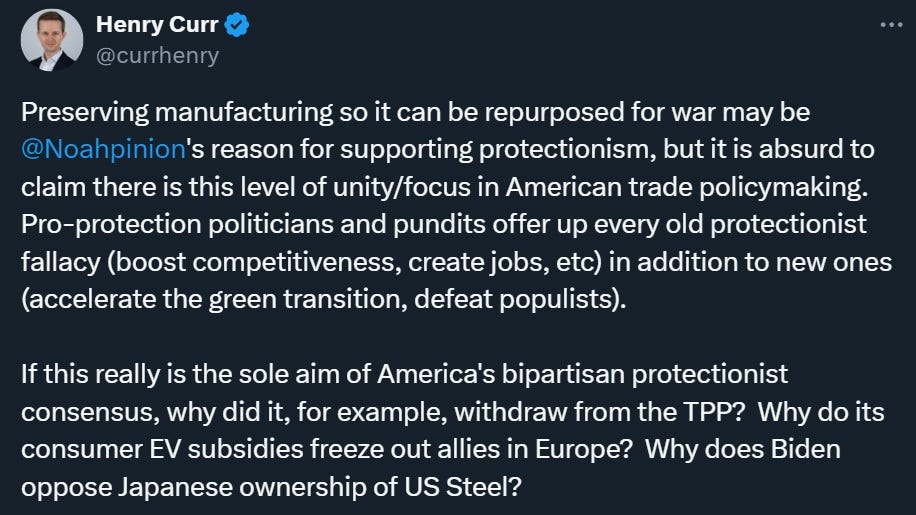

After reading this post, Henry Curr, the economics editor of The Economist, simply denied that a national security motive figures prominently among the Biden Administration’s reasons for tariffs and industrial policy, and attributed everything except export controls to populist pressure and special-interest pandering:

I am astonished by Curr’s apparent failure to actually read what the architects of the policies say about their purpose. For example, here are public remarks by Jake Sullivan, Biden’s National Security Advisor, and one of the principal architects — if not the principal architect — of Biden’s policy approach:

A modern American industrial strategy identifies specific sectors that are foundational to economic growth, strategic from a national security perspective, and where private industry on its own isn’t poised to make the investments needed to secure our national ambitions….

America now manufactures only around 10 percent of the world’s semiconductors, and production—in general and especially when it comes to the most advanced chips—is geographically concentrated elsewhere.

This creates a critical economic risk and a national security vulnerability…Our objective is not autarky—it’s resilience and security in our supply chains. (emphasis mine)

And here are some earlier remarks by Sullivan:

We are pursuing a modern industrial and innovation strategy to invest in our economic strength and technological edge at home, which is the deepest source of our power in the world.

Over the summer alone, President Biden signed the CHIPS and Science Act, an Executive Order on Advancing Biotechnology and Biomanufacturing Innovation, and the Inflation Reduction Act, the single largest investment in climate and clean energy solutions in history.

Alongside these investments, we are intensely focused on modernizing our military – the strongest fighting force the world has ever known – the foundation of our deterrence in a turbulent world. (emphasis mine)

Sullivan has reiterated this core idea in numerous speeches and interviews. Here is just one example:

Articles about Sullivan’s approach consistently use phrases like “an industrial strategy to undergird American power”.

It is frankly astonishing that the economics editor of The Economist seems not to have read or listened to any of this. Instead, he appears to have simply assumed a set of motivations for Biden’s policies, based entirely on his own preconceptions about protectionism. This insularity seems like a likely source of The Economist’s failure to even address the national security reasoning behind Biden’s policies.

Some have criticized my assertion that the UK’s war machine was unable to compete with Germany’s in WW2, noting that the UK actually had a higher percent of its workforce in manufacturing at the time. The key to defense production, at least at that time, was actually heavy and chemical industries, in which Germany had a substantial productivity lead. In fact, industrial policy in the mid-20th century was usually about promoting heavy and chemical industries over light industry like textiles; this was probably MITI’s main industrial policy goal in Japan through the 1960s, for example. The UK’s deficiencies in heavy industry required it to get a lot of aid and assistance from the U.S. Lend-Lease program, in the form of equipment like aircraft, machine tools, and tanks. But it is true that the industrial disparity between Britain and Germany in World War 2 pales in comparison to the vast, yawning gulf between the U.S. and China today, which is all the more reason for us to be worried right now.

At this point a good heuristic might be to do the absolute opposite of whatever the prevailing economic sentiment is in the UK. We really have our head up our arse over here

If we're to take the 'national security' argument seriously then that demands something beyond assertion. Does protectionism _actually_ yield an industrial base ready to fight a war?

The US has a de facto system of protectionism for basically all armaments, in that the US doesn't purchase ships, shells, tanks, rifles, etc which are produced in foreign countries. And yet this 'arsenal of democracy' is slow, plagued with quality issues and outrageously expensive.

Noah's position seems to be that by creating a bigger civilian industrial base that this can be quickly re-tooled for national security. Essentially this is an argument to solve protectionism (military industry) with more protectionism (civilian industry).

Having a civilian capability to produce low volumes of low quality cars at high prices doesn't a military capability make.