At least five interesting things: Future of Humanity edition (#72)

AI "bubble"; Tariffs and inflation; African solarpunk; Mass extinctions; De facto sovereign wealth funds; U.S. immigration policy; EVs and messaging

Hi, folks! I’m back from my travels in Europe, and just getting back into the swing of blogging. I have a bunch of posts lined up, but if there’s anything you really want me to write about, just drop it in the comments!

Here’s an episode of Econ 102, where Erik and I go through a variety of topics:

Onward to the list of interesting things!

1. Liquidity and the AI “bubble”

The American economy’s future — and possibly, the future of American politics — hinges on the question of whether AI will have a big crash. In a previous post, I wrote that the question likely hinges not on traditional “bubble” processes like speculation or extrapolative expectations, but merely on whether or not people are overestimating the speed with which AI can generate real returns.

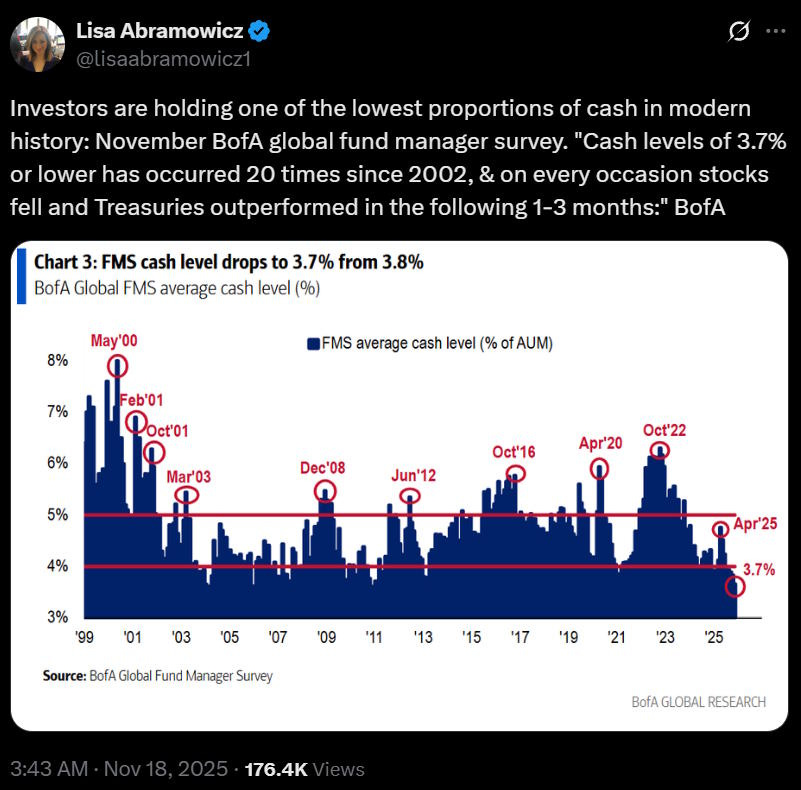

But I might be wrong about that. There might also be more traditional “bubble” processes at work — herd behavior, or speculation, or psychological FOMO, etc. — that might be driving some real AI investment. If so, one warning sign we’d want to watch out for is a drying up of investor liquidity.

In lots of economic models of financial bubbles — the extrapolative expectations model, the information overshoot model, etc. — the bubble stops when people simply run out of more cash to throw into the frenzy. So I get worried when I see stories about AI investors running out of cash:

In the recent past, big tech companies like Google and Meta funded — or at least, could have funded — their AI expansions out of their own profits. But the WSJ has a story about how data center builders are starting to have to borrow instead of just redirecting the cash from their core businesses.

That’s ominous, because that process can’t go on forever.

2. Tariffs and inflation

Economists were right about the fact that Trump’s tariffs would hurt U.S. manufacturing by making it harder to purchase intermediate goods. Trump should have listened to the economists about this.

But were economists wrong about the inflationary effects of tariffs? JD Vance seems to think so:

Now first of all, it’s pretty foolish to make sweeping claims about the economics profession based on a missed forecast. The economics profession, in general, isn’t in the business of macroeconomic forecasting (because none of its forecasting methods are very effective). And even if it was, forecasting is inherently an inexact science; sometimes, forecasters are going to get it wrong.

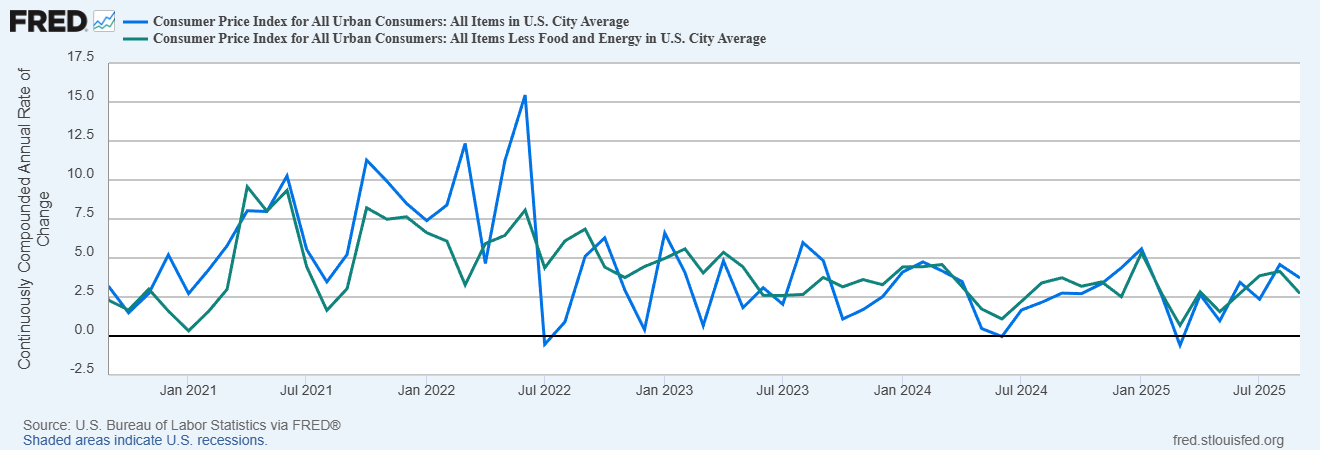

That said, it’s a fair question to ask why tariffs haven’t resulted in much inflation yet. Inflation might be trending back upwards — it’s too early to tell — but so far it’s still in the 3% range that it’s been hovering in since mid-2023:

But did economists really think that tariffs would raise inflation substantially? Recall that there’s more than one way that tariffs can affect prices. They raise prices directly, and they make production more expensive — that’s inflationary. But tariffs can also hurt the real economy, causing shocks in the system and an increase in negative sentiment that reduces aggregate demand. Reducing aggregate demand is disinflationary. Here’s what I wrote back in July:

If some sort of economic event scares people, they’ll pull back their spending and try to save money instead. This does two things: 1) it causes a slowdown in growth, because consumers are spending less, and because companies are investing less to meet consumer demand, and 2) it causes a reduction in inflation, because companies are forced to cut prices to maintain their sales to reluctant consumers.

It’s not just me. Economists always knew this was one possibility. Now, some economists at the San Francisco Fed have examined the historical record and found that in fact, demand destruction often cancels out the inflationary effects of tariffs:

[W]e find that a tariff hike raises unemployment (lowers economic activity) and lowers inflation…We also obtain similar results if we restrict the sample to the modern post World War II period or if we use independent variation from other countries (France and the UK). These findings point towards tariff shocks acting through an aggregate demand channel.

But just because tariffs are often deflationary doesn’t mean they’re good. The way they create deflation is by harming the economy so much that people stop spending and prices go down! Right now, Trump’s tariffs are probably pushing up on prices modestly on net, increasing inflation by maybe 0.5 percentage points — not a huge amount. But the reason they might only be having such a minor effect is that they’re also causing mild economic weakness that’s pushing down on prices.

Basically, this is a case where one harm of tariffs partially cancels out another harm from tariffs. That’s not a good thing, and it’s not a reason to stop listening to economists. Quite the opposite, in fact.

3. Solarpunk is the future of Africa

I’m constantly amused by the fact that the 1980s/90s cyberpunk visions largely came true, and I enjoy speculating about what future visions might come true next. One candidate is “solarpunk”, but so far, that’s mostly just an artistic aesthetic rather than a fully fleshed-out future vision. Singapore has cool-looking plants on buildings, but otherwise it’s just a pretty standard cyberpunk metropolis.

But Skander Garroum makes a convincing case that solarpunk is actually the future of Africa, in a way that cyberpunk was the future of Asia and parts of the U.S.:

Basically, Africa has weak states that aren’t good at providing infrastructure. So solar power is electrifying the continent, because it can be built in a distributed fashion — and because Africa is very sunny, so solar works especially well.

Some excerpts from Skander’s post:

What’s happening across Sub-Saharan Africa right now is the most ambitious infrastructure project in human history, except it’s not being built by governments or utilities or World Bank consortiums. It’s being built by startups selling solar panels to farmers on payment plans. And it’s working.

Over 30 million solar products sold in 2024. 400,000 new solar installations every month across Africa. 50% market share captured by companies that didn’t exist 15 years ago. Carbon credits subsidizing the cost. IoT chips in every device. 90%+ repayment rates on loans to people earning $2/day…

The grid that never came turned out to be a blessing. While development experts spent 50 years debating how to extend 20th-century infrastructure to rural Africa, something more interesting happened: Africa built the 21st-century version instead.

Modular. Distributed. Digital. Financed by the people using it, subsidized by the carbon it avoids.

Cyberpunk was a vision of states coexisting alongside — and sometimes being controlled by — powerful corporations. Perhaps solarpunk is a vision of an anarcho-technological future filled with weak states, where independent individuals and small communities have to take technology into their own hands — a fundamentally African future.

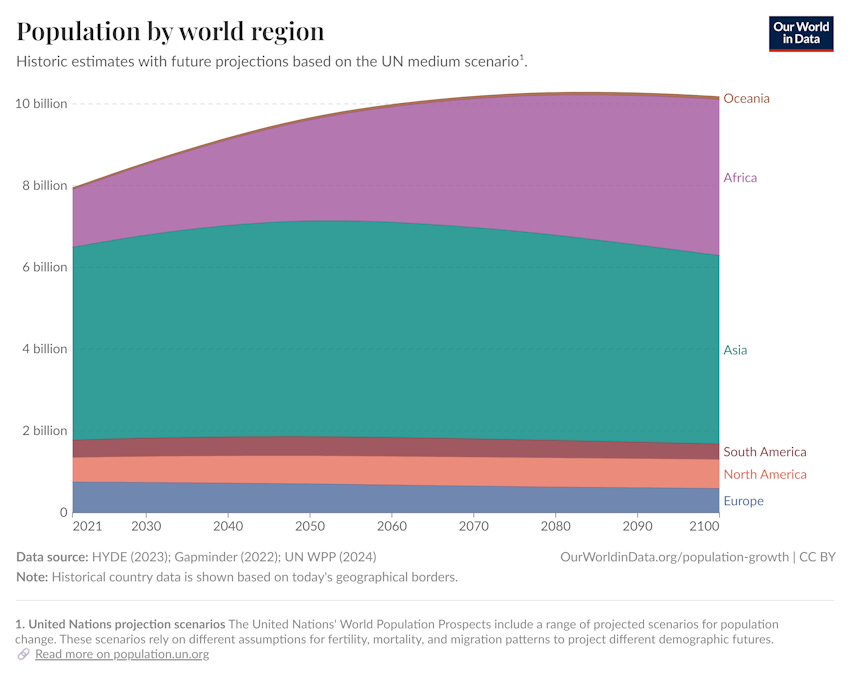

And that’s important, because the future of the human race is the future of Africa:

4. Good news about mass extinctions

One of the more depressing facts about the modern world is that humans are causing a mass extinction. Go to the Wikipedia page for “Holocene Extinction”, and it says:

The Holocene extinction, also referred to as the Anthropocene extinction or the sixth mass extinction, is an ongoing extinction event caused exclusively by human activities during the Holocene epoch…Widespread degradation of biodiversity hotspots such as coral reefs and rainforests has exacerbated the crisis.

The fact of the human-induced mass extinction comes up again and again in discussions of environmental policy. As well it should; animals and plants have no natural representation in human society, so if we care about their well-being, we need to fight very hard to keep it on the agenda.

Except here’s something interesting: The “Holocene extinction” may already be ending:

A new study by Kristen Saban and John Wiens with the University of Arizona Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology…revealed that over the last 500 years extinctions in plants, arthropods and land vertebrates peaked about 100 years ago and have declined since then. Furthermore, the researchers found that the past extinctions underlying these forecasts were mostly caused by invasive species on islands

For their study, Saban and Wiens analyzed rates and patterns of recent extinctions, specifically across 912 species of plants and animals that went extinct over the past 500 years. All in all, data from almost 2 million species were included in the analysis…

Somewhat unexpectedly, the researchers found that in the last 200 years, there was no evidence for increasing extinction from climate change…For some groups, such as arthropods and plants and land vertebrates, extinction rates have actually declined over the last 100 years, notably since the early 1900s…

One of the reasons for declining extinction rates “is many people are working hard to keep species from going extinct. And we have evidence from other studies that investing money in conservation actually works.”

There might be an environmental Kuznets curve at work here — as countries get richer, they might have more concern for animals, and fight harder to protect habitats. Also, needless to say, richer societies hunt wild animals a lot less.

In other words, we should take heart — there is something we can do to stop habitat destruction and mass extinction, and we’re already doing some of it.

5. Was George W. Bush right about Social Security?

The wheels started to come off of George W. Bush’s presidency in 2005. Even before Hurricane Katrina, the financial crisis, or the growing pessimism over the Iraq War, Bush tried and failed to implement a scheme to invest some of the Social Security trust fund in higher-yielding assets like stocks. His defeat marked the beginning of a long downward slide in popularity.

But was Bush wrong? Via Marginal Revolution, I just came across a very interesting paper in the Journal of Economic Perspectives by Chien, Du, and Lustig, arguing that Japan has been reducing its sovereign debt by using a slightly similar scheme:

Japan presents a striking puzzle in public finance. Government debt exceeds 200 percent of GDP, budget deficits have persisted for decades, and economic growth has been sluggish. Yet inflation has remained subdued, and no major debt crisis has emerged. Understanding how Japan has managed to defy the standard logic of debt sustainability is the starting point for our analysis.

The key lies in the Japanese public sector’s operation of a de facto sovereign wealth fund. Unlike countries such as Norway and Saudi Arabia, which fund such vehicles with national savings from natural resources, Japan finances its investments largely through domestic borrowing at very low floating interest rates. While the risk premia on these investments have generated strong returns over the past two decades and supported debt sustainability, this strategy exposes the government to considerable interest rate and exchange rate risks.

So was Bush right? Should we have just put Social Security money into stocks, thus reducing the federal government’s future liabilities? As Chien et al. note, doing this comes with substantial risks — adverse macroeconomic events can end up making government debt even worse, or make bondholders lose money. That risk was why Bush’s scheme got scotched in the first place. And Chien et al. note that many of the factors that allowed Japan to earn a good return on its “sovereign wealth fund” simply aren’t present for the U.S.

Still, I think it’s worth looking into the possibility of having the U.S. government get more upside from the U.S. stock and real estate markets. This is something I plan to write about more.

6. Who is in control of America’s immigration policy?

Remember that time that Trump’s ICE agents raided a South Korean battery factory in Georgia, arrested a bunch of Korean workers, kept them in terrible conditions, and caused a diplomatic incident, thus threatening U.S. technology, investment, and alliances all at the same time?

Well, Trump doesn’t seem happy about it:

In fact, Trump has harshly and publicly criticized the ICE raid multiple times now, and the White House has officially apologized to South Korea for the incident.

Which raises the question: Who is actually making immigration policy in Washington? The obvious answer is “Stephen Miller”, but the truth may be even worse. The raid may have been carried out by low-level ICE officials trying to meet Stephen Miller’s numerical quotas for arrests and deportations:

[A]ccording to an immigration attorney representing several arrested workers, ICE agents chose to arrest the Korean workers to fulfill the quota of 3,000 daily immigrant arrests set by White House Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller.

In other words, the answer to “Who is making immigration policy?” is “no one”. There are no smart people in Washington, D.C. deciding whether a South Korean battery factory worker is a better person to arrest than an MS-13 gangster. ICE has simply been unleashed on the country and told to go arrest and deport a bunch of people, with no thought given to which people to focus on deporting. There’s no one driving this bus.

7. A good article on China, EVs, and the U.S.

I’ve been arguing that the U.S. is losing the technological future to China because we’re failing to master the Electric Tech Stack — the package of new energy technologies that includes batteries and electric motors. And I’ve argued that the reason we’re falling behind is ideological — we still think the Electric Tech Stack is about climate change rather than about power.

Now other people are starting to say the same. Here are some excerpts from a very good Channing Lee op-ed in The Hill:

Now, China commands 60 percent of global battery electric vehicle sales and dominates the battery supply chain that will power tomorrow’s cars, trucks and buses. America barely reaches 16 percent…It didn’t have to be this way. It was an American company — Tesla — that reintroduced electric vehicles into modern driving…

[But] the U.S. took a wrong turn. Instead of focusing on the electric vehicle as a breakthrough technology, Washington framed it as an environmental issue — one that remains politically divisive…That narrow framing had global consequences. While we debated environmental incentives, China was building the foundations of a new industrial order…

Electric vehicles are not just clean cars, but rather computers on wheels, connected to data, chips and infrastructure. Losing the electric vehicle race means losing leverage over critical technology standards, supply chains and industrial jobs. This isn’t just about automakers; it’s about national power and the future of our tech ecosystem…

Electric vehicles aren’t a climate accessory. They’re the next platform for global technological power.

Well said. A lot more people need to hear this message. It’ll take a long time and a lot of shouting for Americans to start seeing electric technology as being about something other than climate.

Well at least the Africa part was positive

I fear the people who take the decisions are the wrong people. I read about a Congressional Committee hearing of the senior executives of the American motor car industry where someone asked how many of them had come to Washington in private jets? They all had come that way. We don’t have anything that rich in the UK but we seem stuck in a quagmire when it comes to decisions affecting anything other than private profit. A Lower Thames Crossing tunnel cost more in environmental reports than a Norwegian tunnel was built of a similar length.