How liberal democracy might lose the 21st century

A scary little theory about information and freedom.

I was raised in an age of liberal triumphalism. Liberal democracy won the 20th century — imperialism, fascism, and communism all collapsed, and by the end of the century the U.S. and its democratic allies in Asia and Europe were both economically and militarily ascendant. Even China, which remained an autocracy, liberalized its economy and parts of its society during this time. Even scholars who turned up their noses at Francis Fukuyama’s “end of history” were generally favorable to arguments that capitalism and/or liberal democracy fostered peace, happiness, and prosperity. There was an overwhelming sense that freedom — the freedom to speak your mind, to live as you liked, to buy and sell what you wished — was the thing that won.

Just two decades later, that idea is deeply in doubt. The wave of democratization and social liberalization went into reverse. The U.S. has been riven by social and political chaos, and its weaknesses in manufacturing and homebuilding have been starkly exposed. Meanwhile China, the ascendant superpower of the early 21st century, has moved back toward a more dirigiste economy and a more totalitarian society under Xi Jinping.

A number of people I know who travel to China these days come back with starry-eyed tales of how wonderful it is compared to the U.S.:

Now, let’s not get carried away here. The asylum seekers fleeing China for the U.S. might disagree, as would many regular Chinese people whose nest eggs have been destroyed by the real estate bust. Glittering new shopping malls and train stations might simply be at the beginning of their capital depreciation cycle. Chinese apps and gadgets might simply be a case of technological leapfrogging that will eventually be leapfrogged in turn. High-speed rail might turn out to be a waste of resources in many areas. It’s important to remember that China is only about 30% as rich as the U.S., even by the most optimistic measures.

And yet there’s no doubt that China’s cities are much cleaner and safer than San Francisco or NYC. Meanwhile, China can make electric vehicles, batteries, and computer chips galore, while it has yet to be shown that America can do the same. China can provide plentiful housing to its people (sometimes too plentiful), while America struggles with chronic housing shortages. China is beating the U.S. handily in terms of switching to green energy. Nor is China’s strength limited to manufacturing — TikTok is so well-made and addictive that it has outcompeted homegrown American short video services in their home market.

And despite the U.S.’ well-documented difficulties, its liberal democratic allies are in an even worse condition. Meanwhile, China is gathering a powerful network of allies — Russia, Iran, and North Korea — putting paid to the idea that autocracies can’t cooperate, and forming a coalition that might militarily outmatch the West already. And although it’s far too early to draw conclusions about political regimes, the possible return of Trump despite Biden’s many successes contrasts notably with the stability of Xi Jinping’s rule despite his many missteps.

China hasn’t yet proven the superiority of its system, but its successes raise the uncomfortable question: Can this be what wins? Can universal surveillance, speech control, suppression of religion and minorities, and economic command and control really be the keys to national power and stability in the 21st century? How could that be true, when those same things failed so comprehensively in the 20th?

I don’t know. But it’s useful and to think about how and why totalitarianism might be well-adapted to the world of the 21st century. In fact, I have a theory of how this might be true. This theory is only a conjecture — it’s something I don’t believe in, but also something I can’t yet convince myself is wrong. It’s a refinement and extension of some of the things I’ve written about before, but over time I’ve begun to bring these ideas together in a more coherent form.

So here you go: a theory of how totalitarianism might naturally triumph. The basic idea is that when information is costly, liberal democracy wins because it gathers more and better information than closed societies, but when information is cheap, negative-sum information tournaments sap an increasingly large portion of a liberal society’s resources. Remember that I don’t believe this theory; I’m merely trying to formulate it.

Liberal democracy as an information aggregator

Let’s start with Friedrich Hayek. Hayek had a theory of why capitalist economies would outperform command economies. His theory was all about information aggregation. Basically, the function of an economy, as he saw it, is to give people as much as possible of what they want given scarce productive resources. And people themselves have a lot more information about both what they want, and about how to use productive resources efficiently, than a central planner does. The function of a market, Hayek argued, was to aggregate those dispersed small bits of useful knowledge in order to better inform production decisions:

The peculiar character of the problem of a rational economic order is determined precisely by the fact that the knowledge of the circumstances of which we must make use never exists in concentrated or integrated form but solely as the dispersed bits of incomplete and frequently contradictory knowledge which all the separate individuals possess. The economic problem of society is thus not merely a problem of how to allocate “given” resources—if “given” is taken to mean given to a single mind which deliberately solves the problem set by these “data.” It is rather a problem of how to secure the best use of resources known to any of the members of society, for ends whose relative importance only these individuals know. Or, to put it briefly, it is a problem of the utilization of knowledge which is not given to anyone in its totality.

The way markets did this, Hayek thought, was through prices. Prices are information. If making steel with blast furnaces is expensive and making it with electric arc furnaces is cheap, that tells steel companies they should be making more of their steel with the latter technology and less with the former. If broccoli is expensive and cauliflower is cheap, that tells farmers they should produce more broccoli and less cauliflower. And so on. Whereas if you had a command economy, the poorly informed central planners might mistakenly decide that blast furnaces and cauliflower are perfectly good, and we should make more of those.

Or, in meme form:

Now, this argument is only for capitalism — economic liberalism — not for democracy or for social liberalism. But it’s easy to think of representative democracy as another information aggregation mechanism — a way of finding out what voters want and putting those wants into policy by simply letting people choose their leaders. And it’s easy to think of free speech as an information aggregation mechanism — a way of finding out what people think through a “marketplace of ideas”.

These aren’t perfectly efficient methods of information gathering, but they probably gather a lot more information than societies where autocrats listen only to their cronies, where government propaganda and censorship control the public discussion, and where leaders are chosen via backroom power struggles among a small elite.

Information aggregation isn’t the only theorized mechanism for the effectiveness of liberal democracy. Another theory is inclusiveness — the idea that liberal democracies make people feel more of a sense of ownership and voice in society, and that this solidifies support for the system. A third theory is based on public goods — the idea that in a democracy, leaders have to satisfy a broader constituency than in an autocracy. And so on. I am not trying to dismiss, deny, or downplay any of those ideas. But just as a thought exercise, let’s run with the idea that information aggregation is the primary strength of liberal democracies, and see where that takes us.

Economists take Hayek’s ideas very seriously, and in the decades following his seminal work there has been a lot of theorizing about the economics of information aggregation. Two key papers in this literature are Grossman and Stiglitz (1980) and Hirshleifer (1971). Both deal with the economics of financial asset selection — basically, stock-picking. But because the models are built on different assumptions, they arrive at almost opposite conclusions.

In brief, Grossman and Stiglitz assume that information about the value of a stock is costly. In order to figure out the proper price to pay for a company’s stock, someone has to actually go figure out how valuable that company is, and that takes time and effort. If stock markets were perfectly efficient — if all you had to do was to look at the stock price to tell how much a stock is worth — nobody would go do the hard legwork of gathering the information in the first place. So markets can’t be efficient; in order for prices to reflect fundamental values in the long term, someone has to be able to make money in the market in the short term by gathering information and using that information to correct mispricings.

Hirshleifer, on the other hand, assumes that information about fundamentals will eventually come to light on its own. If everyone just sits there and waits to see how well a company does, they’ll know how much to pay for its stock. But at the same time, he assumes there’s a big private reward for anyone who goes out and figures out that information in advance, because that person will be able to trade on the temporary mispricing before the information becomes public. So there’s a tournament between a bunch of investors who all try to beat each other to the punch. This effort is wasted, since the information would have come out on its own soon anyway.

Grossman and Stiglitz (1980) and Hirshleifer (1971) represent two very different worlds — a world of costly information vs. a world of cheap information. In the world of costly information, anything that brings down the cost of gathering information makes the aggregator — in this case, the stock market — more efficient. But in the world of cheap information, competition over that information produces waste and makes the market less efficient.

So if liberal democracy is mainly a collection of information aggregators, we can use these two papers as metaphors to imagine two very different worlds — a world of costly information, vs. a world of cheap information. In the world of costly information, liberal institutions like free markets, free speech, and elections reduce information costs, and make the ultimate social outcome more efficient. But in a world of cheap information, tournament effects — costly, wasteful, negative-sum competitions over the private control of information — might dominate.

In other words, my scary little conjecture is that as information gets cheaper, liberal information-aggregating institutions might become less and less useful, while totalitarian information control goes from a liability to an asset because it limits wasteful tournaments.

Let’s put this conjecture in concrete terms and apply it to some of the issues of the day.

Information tournaments in financial capitalism?

The most obvious application of Hirshleifer (1971) and Grossman & Stiglitz (1980) is…exactly what the papers were designed to explain. The stock market.

From the late 1940s through the early 1980s, the U.S. finance industry represented about 10-12% of corporate profits and perhaps 4% of total GDP. Today those numbers are closer to 30% and 8%, respectively. As Thomas Philippon has shown, a large fraction of finance’s increased cost and increased profitability comes from asset management — basically, selecting which stocks, bonds, houses, cryptocurrencies, and so on to allocate Americans’ wealth to. We are spending ever more resources picking stocks. This absorbs a huge percent of the country’s top talent — even now, almost two decades after the financial crisis, almost 40% of graduates from Harvard and Princeton go into either finance or consulting.

Whether this massive allocation of resources to asset selection improves economic outcomes is highly questionable — economists argue back and forth about whether it’s too much, too little, or just right. It’s possible that America’s continued economic growth relative to other rich countries in Asia and Europe comes at least in part from the fact that we allocate more capital with markets and less with banks. But even if this is the case, that doesn’t prove that the greater efficiency is worth the greater cost Americans pay — 8% of GDP is a lot. Denmark and Sweden achieve similar productivity levels with less than 5% of GDP spent on finance. Is America wasting its best and brightest on Hirshleifer-type tournaments?

Now let’s think about China. China is still much poorer than the U.S., so a direct comparison of efficiency is difficult. There are certainly plenty of cases of massive capital misallocation in China — most importantly, the ongoing real estate debacle. China’s glut of unsold EVs might also be a case of misallocation, though it remains to be seen whether this is mere stepping stone en route to a more technologically advanced and profitable industry.

But let’s compare China’s flagship EV company, BYD, with America’s flagship company, Tesla. The two are roughly equivalent in sales, and are generally reckoned to be two of the world’s top manufacturing companies. But the financial input required to build them was very different. Tesla’s growth — after an initial phase when it got a bunch of cheap government loans — required the extraordinary salesmanship efforts of Elon Musk, the country’s most flamboyant business star. Although the company’s Model 3 was eventually a roaring success, the capital cost of producing the vehicle came very close to bankrupting the company. Musk had to engage in constant public fundraising, spending huge amounts of time on Twitter — an effort that arguably eventually drove him a bit insane. He had to get extremely creative with financial engineering, even cannibalizing some of his other businesses. And it’s not even clear whether this effort would have been successful without relocation of a bunch of Tesla’s production to China.

BYD, in contrast, never had to scrape and scramble and desperately scream for financing. Despite going through a number of very rough patches, it continued to enjoy generous and often subsidized funding through Chinese state-controlled banks. Now it has matched Tesla in terms of sales, and arguably in terms of technology.

This doesn’t mean China produced a market-leading EV giant more cheaply than America did — to count the full costs, we would have to look across not just the car industry, but across all industries, since all companies compete with each other for capital. That is beyond the scope of current research, and well beyond the scope of a blog post. But the fact that Tesla had such a harder time convincing markets of its eventual success suggests the possibility that the U.S. system overpays for asset selection.

In Tesla’s case, of course, the information tournament wasn’t a Hirshleifer (1971) type thing, with hedge fund managers racing to be the first to figure out how good the company was — instead, it was Elon Musk having to spend his scarce time and energy shouting over a whole bunch of other people who wanted capital, as well as over short-sellers who believed Tesla was about to collapse.

This example suggests that we should generalize the idea of information tournaments from overcompetition for scarce timing to overcompetition for scarce attention. I actually can’t find any game theory papers on this topic (which probably just means I’m not using the right search terms, and I should just go ask a game theorist). But it’s not hard to imagine how a model like this might work. Suppose there’s a decision-maker choosing to allocate investment capital between several competing claimants who each claim they’ll provide the highest return. And suppose that the decision-maker can only process a limited amount of information, so that the more resources you spend shouting for her attention, the greater the chance she’ll pick you to invest in. It’s pretty easy to see how this could produce an inefficient equilibrium like the one in Hirshleifer (1971), where everyone shouts too loud.

Information tournaments in electoral politics?

Now let’s apply that model to another key part of liberal democracy: elections. There is plenty of evidence that U.S. politicians spend much of their time campaigning for office rather than governing. Much of that time is spent raising money for campaign messaging. Every member of the U.S. House of Representatives is up for reelection every 2 years, requiring a continual cycle of fundraising; incoming House members are advised to spend four hours out of every day raising money. Other estimates give a number of 30 hours a week.

Thirty hours a week! That’s a staggering amount of time — almost a full-time job. Those 30 hours a week come directly out of time that legislators could otherwise spend governing the country. This is an information tournament — only one candidate can win any election, but all the candidates have an incentive to spend more resources shouting down their opponent.

And as a result, much of the actual work of governing the United States — writing legislation, reading legislation, thinking about policy positions to take, etc. — is done by staffers rather than by politicians themselves. In 1960s Japan, it was said that politicians “reign” while bureaucrats “rule”; in America, it’s not a huge exaggeration to say that elected legislators merely reign while staffers rule.

This produces a peculiar age pattern in our government. The need for constant fundraising and campaigning is lessened by tenure in office — politicians who have been in office for 20 years have name recognition and connections that allow them to fundraise and win reelection more easily, so our legislature has increasingly become a gerontocracy. But actual governing is done by staffers in their late 20s. There is thus a notable dearth of people in positions of legislative power in their prime productive years — 30s and 40s. It’s all oldsters pressing the flesh while youngsters write the laws.

This is not the only reason why America’s legislature is commonly regarded as dysfunctional, and why Congress’ approval rating is among the lowest of any institution in the country. The abundance of veto points, especially the filibuster and the debt ceiling, also contributes to legislative gridlock. But the fact that your average legislator is basically just a fundraiser seems like a recipe for a dysfunctional, ineffective nation.

China’s leaders are not democratically chosen, which probably makes them worse at aggregating the preferences of the populace. But it’s at least conceivable that the Chinese system might give rulers much more time to do the actual business of ruling.

Information tournaments on social media?

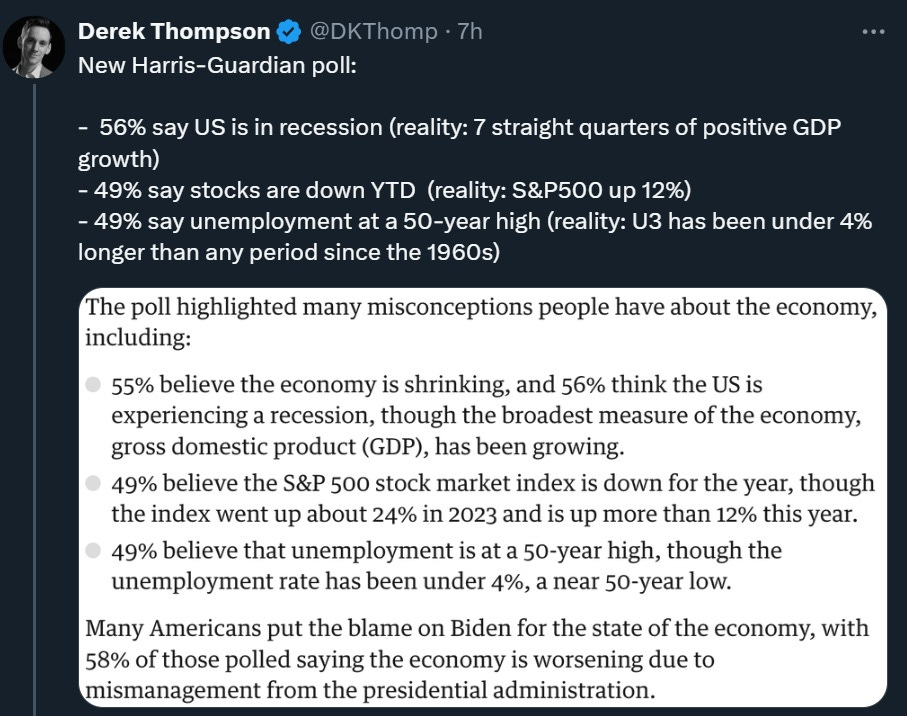

Finally, we can apply the idea of information tournaments to freedom of expression — to free speech, press freedom, freedom of assembly, and all the other things that are supposed to make the marketplace of ideas function in a liberal democracy. Anyone who has watched public opinion play out in the most recent electoral cycle has probably noticed that the public is getting a lot of basic facts about the economy very wrong:

Many observers of this situation have lamented that this widespread misinformation comes in spite of the fact that information is cheaper and more abundant than ever:

But what if the abundance of information is the cause of widespread misconceptions? Among that “information” there is tons and tons of misinformation — some of it spread unwittingly by people who just don’t know any better, but much of it active disinformation spread by political partisans or even by foreign governments.

Since misinformation doesn’t have to be true — it just has to fit people’s preconceptions or their partisan agendas — it’s much less costly to produce than true information. At this point I trot out the old quote that “a lie can travel halfway around the world before the truth can get its boots on.” What this means in practice is that either an idiot or a liar can produce a bunch of plausible sounding falsehoods in the time it takes you to debunk just one of those falsehoods. This isn’t just theory; there’s actual research showing that misinformation spreads faster than true information on social media.

Of course, it’s possible to debunk most of the B.S. out there — it just takes a massive investment of time and effort. Some of the smartest people in the nation have been de facto drafted into becoming part-time or even full-time Twitter warriors, fighting valiantly — and often failing — to stop the public from believing an overwhelming sea of B.S. This looks like another kind of information tournament — a massive waste of resources, talent, and time.

Meanwhile, China’s closed information ecosystem is undoubtedly worse at bringing important viewpoints into the public consciousness — for example, China’s leaders appear to have been taken aback by the “white paper” protests against eternal Covid lockdowns back in 2022. But that lower performance might also come with much lower costs. Chinese society has not devolved into a neverending general shouting match, the way American society has over the last decade. Chinese people might be exhausted these days, but they’re exhausted by work rather than by politics.

A unified theory of liberal democracy’s failure in an age of cheap information

Thinking about all these examples, we can sketch out a general theory of how liberal democracy might be far less suited to the 21st century than it was to the 20th. As information technology has advanced, the costs of gathering information may have fallen to such a low level that the advantages of liberal institutions — markets, elections, and freedom of expression — may be attenuated. At some point, those advantages may fall well below the costs of information tournaments — the inevitable competitive negative-sum shouting, misinformation, campaigning, fundraising, and financial competition that has become an ever-larger piece of how Americans spend their time.

Thus it could be that while China builds cars, Americans argue about trans athletes. While China builds computer chips, Americans spend their time debunking fake economic statistics. While China builds submarines, Americans spend their time doing high-frequency trading. While China builds trains, Americans fundraise for elections. And so on. Meanwhile, thanks to the internet that America invented, China’s leaders can get a still-inferior-but-much-less-crappy idea of which products to build, which policies to enact, and which ideas to embrace than their Maoist and Stalinist predecessors could.

Once more, this theory is just a conjecture, not an assertion of truth. And it’s not a very useful one, either — if liberal democracy just isn’t the most effective way of organizing a society in the age of cheap information, it just means the personal freedoms we’ve come to know and love are on the way out. Sometimes one system simply replaces another after a major technological change — agriculture mostly brought the end of hunter-gatherer bands, industrialization mostly brought the end of monarchies, and so on. If the information age has evolved past liberalism, we’re in for a very dark time, and there’s not much we can do about that.

But we shouldn’t accept this theory as true just because I managed to write a halfway-coherent blog post about it. We should continue fighting for liberal democracy, and hope that technology and human nature allow for its continued victory. We should try to tweak our institutions to prevent our time from being cannibalized by information tournaments — restraining the excesses of high finance, limiting campaign spending in order to give legislators more time to govern, directing more capital to long-term risky high-tech projects, and so on. Liberalism may or may not still have the advantages it had in the 20th century, but whether or not it does, we shouldn’t give it up without a fight.

Possible objection is that BAD information is cheap and GOOD information is expensive. It is easy for people to have access to information that supports their already-existing vibes but difficult for people to get information about issues with a lot of complex moving parts. Sources of bad information may also work overtime to discredit the good information sources.

I think it's perfectly plausible to spend a week in a CBD of a city which contains millions of people and come away with a sense of it being extremely clean and its streets safe at night, but this is an experience I have had all over the world.

The sense I always got about Chinese cities is that there is a level of cleanliness evident when the effort is taken in very specific places, but that there is also a level of disrepair and dinginess that can usually be found an extremely short distance away if you walk the right direction. It built for me the sense of three Chinas; the first China is Future China, the pre-depreciation China that you mention. It feels like next year. Big city CBDs felt this way, Hong Kong felt this way. The second China is Yesterday China, which is post-depreciation China that you can experience outside the inner ring roads. It feels like a shabby industrial city that someone is maybe trying to do urban renewal on, or maybe someone tried and it really didn't take off. Kunming and Fuzhou felt like this to me outside of a very restricted area. The third China is 1960 China, where you begin to really have the sense that you are in a nation with 1/3 the income of a Western one. This is what you experience if you travel between cities of any type and stop for any reason. I feel like travelers are likely to only glimpse the second China and not even have any contact at all with the third, especially if they are traveling there for conferences or the information economy. If you travel there for industry you will have a lot of contact with the other Chinas.

The feeling I got the first time I went to big Chinese cities was "this city is so Chinese", and then by the time I came back through after experiencing the central mainland, especially the industrial third tier cities, was "an extensive veneer of modernity has been put on top of this place."