Anti-neoliberalism is not enough

Bashing this bogeyman is no substitute for a new policy program that works.

Matt Yglesias has been writing a series of posts on “neoliberalism and its enemies”, and I strongly recommend the whole series. In Part 1, he argues that the shift to “neoliberalism” in the 1980s was far less dramatic than popularly believed, and that a more consequential shift was the rise of anti-growth NIMBYism. In Part 2, he argues that trade protectionism can be useful for helping the U.S. preserve its military capabilities vis-a-vis China, but is generally harmful to people’s standards of living. In Part 3, he argues that income redistribution has been a lot more successful than anti-neoliberals believe, and shouldn’t be abandoned. And in Part 4, he argues that many of the problems people attribute to neoliberalism were actually just problems of deficient aggregate demand after the Great Recession.

There are many good points here. I strongly agree with some of Yglesias’ arguments (especially on the harms of NIMBYism and the usefulness of redistribution), and I disagree with some others, but they’re all worth reading. Today, though, instead of going through Matt’s points and responding to them one by one, I want to give some of my own thoughts on neoliberalism — and, more importantly, on the progressive economic paradigm that styles itself as a repudiation of neoliberalism.

Neoliberalism was more important as an organizing principle than as a set of policies

One thing I think Matt gets very right is that the shift to neoliberalism in actual U.S. policy wasn’t nearly as dramatic as our potted histories would have us believe. Pretty much every anti-neoliberal manifesto repeats a catechism about how the late 20th century saw America turn toward low taxes, deregulation, smaller government, and free markets in general, leading to increased inequality and generally worse conditions for the working class.

But is it true? Did that really happen? In some ways — lower tariffs, weaker unions, deregulation of the financial industry — the story fits the facts. In many ways, however, the potted history that we see hammered home ad infinitum is a caricature of what really happened. I wrote a post about this a couple of years ago:

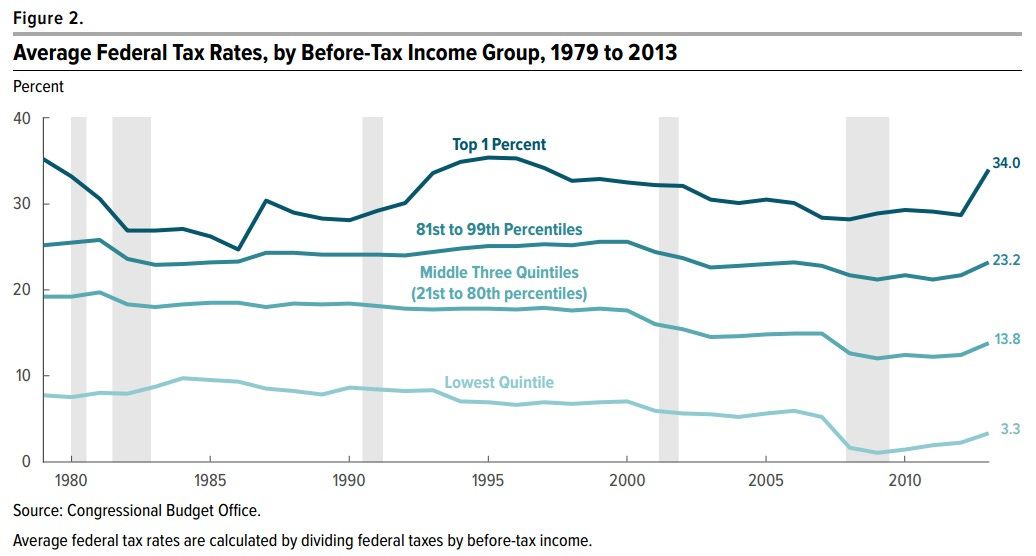

For example, take taxes. Top tax rates were cut, but the actual amount of their income that the rich pay in taxes didn’t really fall much over the whole period:

(And yes, it’s the same when you add in state and local taxes.)

Meanwhile, as Yglesias notes, the U.S. welfare state actually got bigger in the “neoliberal” age, even before the 2008 crisis:

Poverty fell substantially as a result of this increased redistribution. Inequality did rise, but by somewhat less than the headline numbers would have us believe. Median incomes continued to grow, albeit a bit less slowly than in the postwar period.

And regulation continued to grow overall in the neoliberal era, despite some high-profile deregulations in industries like finance.

That said, I do think the shift in economic thinking and policymaking from the late 1970s through the 1990s was important. And although the word is exhaustingly overused and a little bit precious-sounding, I do think “neoliberalism” is probably the best way to describe this shift.

Basically, I think economic paradigms are more important as ways of thinking about policy, rather than as lists of actual policies. Policy ideas don’t just appear out of the blue — think-tankers and writers and academics have to generate ideas somehow. And paradigms like “neoliberalism” become sources for ideas. Once you accept the general thesis that government intervention in the economy is bad except in specific well-circumscribed exceptions, then you start thinking “Hmm, what are some ways we could help America by limiting the government?”. This will guide your brainstorming toward ideas like lowering tariffs, simplifying the welfare state, deregulating certain industries, or replacing pollution bans with cap-and-trade markets.

And even more importantly, it will guide your ideation away from things that seem like they would obviously increase the scope of government. For example, perhaps it would have been good for the U.S. to do more active industrial policy to promote solar power and electric vehicles back in 2002. But very few people were proposing that — not because the idea had been tried and rejected, and not even because it would be hard to make a theoretical case for it under basically “neoliberal” assumptions,1 but because back in 2002, the notion that government had a central role to play in the growth of new industries didn’t fit with the popular paradigm of “How can we get government out of the way?”. Green industrial policy was too out-of-the-box in the neoliberal age.

This principle also applies not just to ideation but to gatekeeping of ideas as well. It’s common to think about policies not just in terms of their final results, but in terms of intermediate goals — “Will this strengthen workers?”, or “Will this simplify the tax code?”, or “Will this give more power to the states?”, etc. Neoliberalism told us that “Will this limit the scope of government?” was a good intermediate goal for policy.

This, I believe, pushed many thinkers to reframe big-government policies as government-limiting ones. A prime example is the Earned Income Tax Credit. The EITC is a welfare policy — it gives cash to poor people. Along with the similarly designed Child Tax Credit, the EITC is a big part of why redistributive welfare spending in America went up in the 90s and 00s. But by framing it both as a tax cut and as alternative to the traditional welfare program (AFDC/TANF), liberals were able to get it past quite a few intellectual gatekeepers.

Neoliberal gatekeeping also prevented quite a few interesting policy ideas from getting seriously considered. In the 2000s, China severely undervalued its currency — pushing back against this would have mitigated the First China Shock and probably led to a more balanced global economy and fewer disruptive effects on U.S. labor markets. Many manufacturers did actually call for the U.S. to label China as a currency manipulator, which would have allowed countervailing steps like conditional tariffs or currency market intervention. The idea was out there.

But the Bush administration chose not to do it. Part of that was geopolitical — Bush wanted China’s support in the War on Terror — but part of it was that things like tariffs and currency market intervention seem like big government mucking around in the economy, and in the 2000s that was seen as something to be afraid of. So even though a successful pushback against China’s currency manipulation would have actually reduced the overall distortion in global markets, the steps required to do that were considered unacceptable because they didn’t fit the image of neoliberalism.

So I think that to gauge the true impact of neoliberalism on policy, you have to look at the proverbial dog that didn’t bark — you have to think about what didn’t get done, rather than just what did get done. And I think that with the benefit of hindsight, we can identify some policy failures that resulted from having to squeeze economic thinking into a paradigm of limited government.

Now that doesn’t mean neoliberalism was a bad paradigm overall, especially when it started out. The idea of limiting government became popular in the 1970s, when regulation was excessive, tax rates were probably too high, the welfare state was poorly designed, and our trading partners generally played by the rules. It was created to address the problems of its day, and just because it outlived those problems and wasn’t fully suited to the problems of later decades doesn’t mean it was a wrong turn in the first place. Whether America could have done much better in the 1980s and 1990s is a debate for another day.

But in any case, most thinkers seem have agreed that neoliberalism is not suited to the challenges America faces in the 2020s. We’re now designing a new paradigm, much as we did in the 1970s or the 1930s. And while conservatives want in on this game, it’s progressives who are really in the vanguard of constructing the alternative. This is good — we do need a new organizing principle for thinking about economic policymaking. Yes, this new paradigm will be inherently limiting, and will squelch some good ideas, especially as the decades go on. But humans seem to need paradigms as thought-organizing devices, so the best we can do is to make the new paradigm as effective as possible.

A good new paradigm is the developmental state

A new paradigm always has to replace, and in some sense to destroy, the old one. But reactive anti-neoliberalism, by itself, is too weak a foundation upon which to build. Simply constructing a mental caricature of what Milton Friedman or Ronald Reagan would do, and then doing the exact opposite of that, will not lead to wise policymaking.

For one thing, neoliberalism was created to address the problems of the 1970s, so if all we do is the opposite, then our policy thinking will be severely limited by whatever was happening half a century ago. More fundamentally, the universe of possible policies is not actually defined by a one-dimensional axis of “more neoliberal” to “less neoliberal”. There are a whole lot of non-neoliberal policies you can do, and you need some way to choose among these.

Frankly, I’m tired of every article about industrial policy, antitrust, tariffs, or child care beginning with yet another version of the same potted 5th-grade-level history about how Bad Old Milton Friedman told us that government was Bad, which ended up making everybody poor and hopeless and led to the election of Donald Trump in 2016 and blah blah. We’ve heard that story. We’re good. You can skip it next time, and just get to the important stuff.

Fortunately, I think two important piece of what the new paradigm ought to be are beginning to emerge from the maelstrom of debate and discussion.

The first piece is to focus on tangible results. This is what Brad DeLong and Stephen Cohen wrote in their 2016 book Concrete Economics, and it rings even more true today. Neoliberalism was indefinite in its promises — it promised to leave things to the market, and that this would result in unspecified increases in material consumption. But nowadays, Americans are starting to get a pretty good idea of the specific things they don’t have, whether because of neoliberalism or anti-growth NIMBYism or for other reasons. A partial list might include:

Cheap high-quality housing located near to employment opportunities

Low and stable inflation

Cheaper medical care

A military-industrial complex capable of resisting America’s powerful new enemies

Public safety and public order

Fewer hassle costs in daily economic life

Cheaper child care

Nicer mixed-use walkable urban areas

Protection from wildfires and floods (the harms of climate change)

Stable food prices

The Abundance Agenda and Supply-Side Progressivism are aimed squarely at providing many of the goods and services on this list. And Jake Sullivan, who has probably done more than anyone to define Joe Biden’s industrial policy, focuses on deterring China and defeating climate change.

The YIMBY movement is focused on the housing piece, but its approach of prioritizing concrete goals over ideology is something that can be transplanted to many other pieces of the new paradigm. YIMBYs support both deregulation and public housing — what’s important is that housing gets built, rather than how it gets built. That can serve as a model for movements to make health care and food cheaper as well. It’s a great sign that Kamala Harris’ campaign has embraced YIMBYism — in fact, I just helped do a fundraiser for “YIMBYs for Harris”.

Mobilizing society’s resources for these concrete goals is not very neoliberal at all. Neoliberalism is agnostic about what people want; the abundance paradigm identifies goals and goes after them. And whereas neoliberalism requires an explicit, well-understood “market failure” to justify each government intervention, the abundance paradigm puts government on an equal footing with the private sector — it assumes that each will have their role to play, and that trying to determine this role ex ante will limit the effectiveness of policy.

This is the second major piece of the emerging new paradigm that I see — the idea that government and the private sector are not enemies, but simply two different parts of the same team. Each institution has its role to play in getting concrete results for the American people.

For example, public-private partnerships were key to the development of Covid vaccines. Private companies created the vaccines, but they relied on government-funded research. Government ensured demand for the private companies’ products — this was what Operation Warp Speed was about. Other private companies manufactured and distributed the vaccines, with government funding and occasional logistical assistance. The two institutions worked together, and the concrete goal was achieved.

Another example is Biden’s industrial policies. The CHIPS Act and the Inflation Reduction Act have touched off a giant investment boom in manufacturing:

This investment is essentially all private company spending. In fact, when the government has come in and tried to build some of this stuff directly, it hasn’t done a very good job of it so far. But at the same time, the massive surge in private manufacturing investment is happening in large part because government subsidies — which sometimes come with implicit purchase commitments attached — have motivate companies to borrow and spend. As a result, manufacturing looks like a growth industry in America for the first time since at least the 1990s, and possibly since the 1960s.

This doesn’t mean that public-private partnerships are always the way to go in the new paradigm. Yes, they’ll be common, but sometimes something is better off when it’s done entirely in-house by the government (e.g. transportation planning) or entirely by deregulated private companies (e.g. building housing on privately owned land). The emerging new paradigm is not ideological about the division of labor between institutions — it’s something that has to be figured out on a case-by-case basis, often by trial and error rather than deep theory.

A focus on concrete results and an institution-agnostic approach to achieving them are what I see as the best two organizing principles to emerge from the quest to replace neoliberalism. I’m not sure what to call this new paradigm. Academics already have a name for it — it’s called the “developmental state” — but that might not be catchy enough for a slogan. On the other hand, “neoliberalism” is a name that’s used much more often by the idea’s critics than by its architects, so maybe the new paradigm will be the same. Maybe we’ll just do it, and then figure out what to call it later.

So anyway, I’m pretty optimistic about a new economic policy paradigm organized around the principles of the developmental state. But I also think that many critics of neoliberalism are getting distracted by an excessive focus on a different organizing principle: the idea of “power”.

Anti-neoliberals focus too much on “power”

When Ezra Klein wrote his manifesto about Supply-Side Progressivism, some progressives pushed back very hard against it. Chief among these was David Dayen, editor of the American Prospect, who wrote a rebuttal called “A Liberalism That Builds Power”. In that post, Dayen argued that the chief goal of the new progressive economics should be building power for progressive interest groups, so that progressive accomplishments are not threatened by future reversals.

In addition to willfully mischaracterizing many of Klein’s positions, Dayen seems to be putting the cart before the horse here. In a democracy, a movement that tries to seize institutional power without providing concrete results is not going to be able to hang on to power for long.

In fact, it’s important to remember that neoliberalism probably survived for a long time not because its adherents sneakily seized the levers of power in smoky back rooms, but because Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton won a bunch of elections and presided over pretty good economic times. Anti-neoliberals tell themselves that the decades of the late 20th century represented immiseration for the American middle and working class, but in fact, purchasing power and wages grew quite a bit over this period, taxes went down for the middle and working class, and the values of people’s stock and housing wealth rose quite a bit. The neoliberal failures of the 21st century — the China Shock, the housing bubble, and the Great Recession — may have obscured our memories of its apparent successes in the decades prior.

But many anti-neoliberal manifestos are absolutely obsessed with the concept that power is something seized rather than something earned. For example, read anything by the economist Joe Stiglitz, who is sort of the godfather of the modern anti-neoliberal movement. Here’s an example for a recent essay he wrote for the Roosevelt Institute:

Under neoliberalism, what was really going on was not a liberalization agenda, it was a “rewriting-of-the-rules” agenda —rewriting the rules in ways that advantaged some groups and disadvantaged others. Rewriting the rules is political. It’s about power…A number of small, subtle changes have made a big difference…

One of our objectives should be to create an economy with no—or minimal—centers of power. Policy can affect the extent of power concentration; we can limit the power of any one person or group with greater decentralization (effectively enforcing strong competition laws) and more progressive taxation. Of course, even then…we will then need to address the remaining power imbalances [by creating] “countervailing power,” such as strong unions……Our emphasis should be on the prevention of the agglomeration of power. But…we need to simultaneously think about countervailing institutional structures and policy actions, such as a stronger civil society and reducing the power of money in our politics.

Now, Joseph Stiglitz is a brilliant man and an incredible economist — one of the best to ever live. But while much of his research does justify more activist policies, he is not a political scientist; as far as I can tell, none of his long and storied research career has been about understanding the sources or the effects of political power. He is not an expert on power, and yet he views it as central to everything.

Stiglitz’ amateurish views on power were on full display in the 2000s, when he delivered fulsome praise for Venezuelan leader Hugo Chavez:

In 2006, Nobel Prize–winning economist Joseph Stiglitz praised the economic policies of Hugo Chávez. The Venezuelan president ran one of the “leftist governments” in Latin America that were unfairly “castigated for being populist,” Stiglitz wrote in Making Globalization Work…In fact, the Chávez government aimed “to bring education and health benefits to the poor, and to strive for economic policies that not only bring higher growth but also ensure that the fruits of the growth are more widely shared.” In October 2007, Stiglitz repeated his praise of Chávez at [a] forum in Caracas, sponsored by the Bank of Venezuela. The nation’s economic growth rate was “very impressive,” he noted, adding that “President Hugo Chávez appears to have had success in bringing health and education to the people in the poor neighborhoods of Caracas.” After the conference, the Nobel laureate and the Venezuelan president had an amicable meeting.

The regime Stiglitz praised ended up immiserating Venezuela with bad economic policies. That outcome was far worse than anything any neoliberal regime I know of, in any region of the world. But Chavez and his handpicked successor Maduro also wielded their power in profoundly evil ways. Now, after a disputed election, Venezuela is devolving into a nightmare of a different kind:

While I’m sure Stiglitz would not endorse these actions, the fact that he failed to see the signs of an emerging dictatorship should make us wary about accepting his theories of power as received wisdom.

Obviously, today’s progressives do not intend to create a Venezuela-style dictatorship. But their ideas about how power functions in society often involve some rather heroic assumptions. For example, I think Jennifer Harris (no relation to Kamala) is one of the sharpest thinkers in progressive intellectual circles these days, and she and I agree on most policies.2 However, I was a bit confused by her assertion in a recent op-ed that closing the carried interest tax loophole would stop private equity from lobbying against government child care:

Ensuring quality child care from birth to kindergarten will take more than just child tax credits. It will require contending with the reach of financial power…because eight of the top 11 child care businesses in the country are now owned by private-equity firms…Many of these firms recently lobbied against a broad-based federal child care benefit because, as one noted, it could “place downward pressure on the tuition and fees we charge”…This is classic corporate extraction…Ms. Harris (and Congress) could end it by closing the carried-interest loophole as part of the looming tax fight next year.

Closing the carried interest tax loophole (which allows money managers to treat their performance fees as capital gains and thus pay a lower tax rate) would, in my view, be a good thing. It would be fair, and it would raise needed revenue for the government. But how would it stop private equity firms from lobbying the government for their own economic interests? Here’s where things get vague.

Treating carried interest as ordinary income certainly wouldn’t shut down the private equity industry. Nor would it shrink private equity profits to the point where they’d be too poor to engage in lobbying — private equity spend $222 million in lobbying in 2020, compared to hundreds of billions of dollars in annual profits. In other words, private equity’s spending on lobbying is an infinitesimal fraction of its total profit, and this would continue to be true if carried interest were taxed at the ordinary income rate.

This is an example of how anti-neoliberals are obsessed with power, but don’t yet have a well-developed theory of how power functions in our society. It is far from the only example. Many progressives have latched onto popular misinterpretations of a single deeply flawed political science paper to conclude that American democracy has been captured by monied interests. And Bernie Sanders and his followers tried to sell wealth taxes as a method for curbing the political power of those rich people, even though — as with the case of carried interest — the effect on actual lobbying spending would be minuscule.

Simply thwacking actors you don’t like with policies that financially inconvenience them is not a way to durably decrease their political power. This is not revolutionary Russia — a higher tax bill is not going to send America’s private equity barons to a Siberian gulag. If anything, it will motivate them to spend more on lobbying, in order to repeal the policies they don’t like.

This doesn’t mean that curbing the political power of corporate interests is a bad idea. It simply means that in a democracy, that has to be accomplished by changing campaign finance law and laws around lobbying. Which requires building popular support for those laws.

In any case, changing the economic system itself to alter the distribution of political power is simply not a workable idea. I thus encourage anti-neoliberals to reduce their focus on power as a goal in and of itself. Power will come — as it did for Ronald Reagan and the neoliberals, and for FDR and the New Dealers — from winning a bunch of elections. And that will come from delivering the American people what they want.

The theoretical case is as follows: Carbon emissions have a negative externality, and technological improvement has a positive externality. These are both market failures. Thus, promoting green technology via the government works to correct two externalities at once. Because technology is nonrival and spills across borders, promotion of green technology does more to decarbonize the rest of the world than carbon taxes, which suffer from a coordination problem.

I also think Matt Yglesias has at times been uncharitable in his characterization of Jennifer Harris’ work. When Jennifer wrote that private equity companies had “lobbied against a broad-based federal child care benefit”, Matt called this “misinformation” and claimed that the PE lobbyists were only opposed to direct government provision of child care. However, when I read the PE financial statement in question, it indeed worried about the competitive threat from “a broad-based benefit with governmentally mandated or funded child care or preschool”. This seems to encompass what Jennifer wrote, rather than the narrower interpretation that Matt gave — the company really was worried that an overly broad subsidy regime would flood the market and reduce its margins. Although we don’t know exactly what the firm’s lobbyists said behind closed doors, given this language, it seems reasonable to think they would lobby for a more narrow child care benefit.

Yglesias had a glaring hole in his neoliberalism piece that maybe you could address.

Healthcare.

The US could copy any one of 30+ health systems from other rich countries and we don't.

We almost had a similar system with universal coverage in the Nixon administration.

But later, there was a basic inability to believe (despite all of the abundant evidence from decades of other countries) that the government being more involved in healthcare can save money and increase coverage. The US is still in thrall of this part of the neoliberal turn. It's what killed Clinton's attempt and the public option in Obama care.

It would be great to get your thoughts.

This has always been one of the challenges of the intellectual left—an academic viewpoint on the nature of power that might or might not be grounded in reality.

The Hegelian Dialectic, which helped inspire Marx in his formulation of Communism should work. A lot of the examples here with an oversimplified money = power (despite, ironically, a lot of these institutions experiencing formative years where the left causes often had substantially more money especially during the Obama era).

Anyway, the world is complex and “both sides” oversimplifying is bad. Money doesn’t equal power so simply (and human beings don’t tend to be so black and white as “evil corporations” or private equity firms. Additionally, just shrinking government and blindly repealing regulation doesn’t lead to better outcomes either.

A lot of folks seem to forget: economic and political systems are not ends in-and-of themselves. They’re meant to make peoples’ lives better and help people achieve things they want. If they don’t do this, they can and should be changed—as they have through history. We shouldn’t be too precise about dogmatically adhering to our “teams” in capitalism, socialism, neoliberalism, communism, or whatever other “ism”.