America is losing the physical technologies of the future

Electrical technology isn't just a climate thing. It's about national power and prosperity.

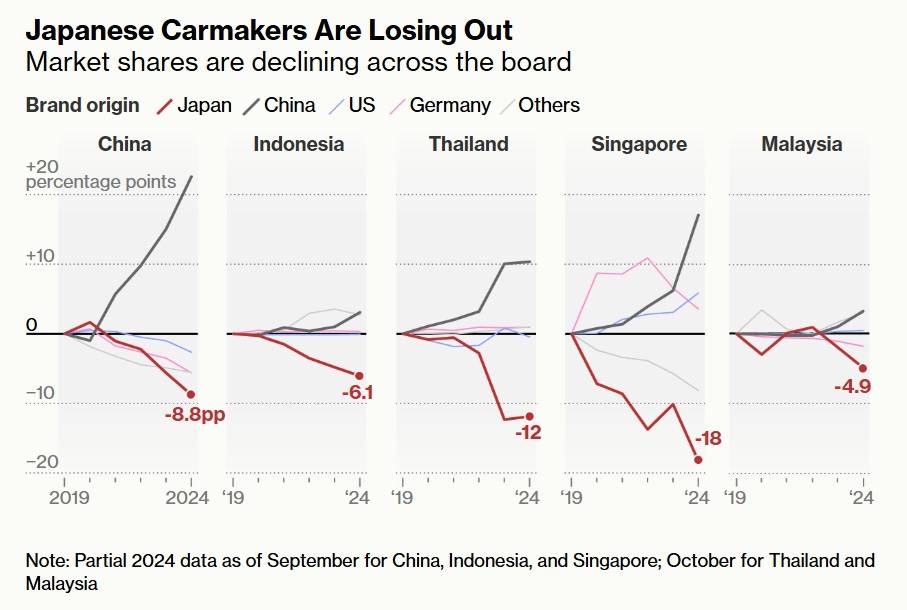

If you’re a little older than I am, you might remember a time, just four decades ago, when the Japanese auto industry was riding roughshod over its American competition. How times change. Nissan just announced a possible merger with Honda, which may end up including Mitsubishi Motors as well. As Bloomberg’s Nicholas Takahashi explains, Nissan has been ailing for a while, with management chaos, outdated products, and plummeting profits. But this merger is the canary in the coal mine — The entire Japanese auto industry is getting smashed by Chinese competition in key Asian export markets:

Japan’s share of U.S. sales is falling as well. All of this is driving disappointing earnings for Japan’s Big Three. The tie-up between Honda and Nissan is supposed to fight back, by leveraging economies of scale. But just as when a bunch of Japanese semiconductor companies combined to form Renesas Technologies, the benefits from consolidation in the car industry will probably end up being limited.

The reason is that the Japanese companies’ fundamental problem is technological. For many years, Japan’s automakers ignored the promise of electric vehicles, instead choosing to focus on hydrogen cars — a dead-end technology. Now they realize they need to catch up, but they’re way behind. As the world shifts rapidly to EVs, BYD, Tesla, and various smaller Chinese companies have eaten the hidebound Japanese automakers’ lunch.

This is a five-alarm fire for Japan, which is already suffering a punishing economic stagnation. But it’s also an important warning for the U.S. We’re watching in real time as a country forfeits leadership in the technologies of the future. On the other side of the world, Germany is not doing much better.

Such technological stumbles have geopolitical consequences as well as economic ones. As Paul Kennedy wrote in The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, the power of nations has historically hinged on their ability to master the key technologies of the day, whether that was gunpowder and sailing ships, modern taxation and bureaucracy, or mass manufacturing.

U.S. leaders know this, of course. With the CHIPS Act, export controls, and various AI-related policies, they’ve recently acted to preserve American supremacy in the crucial mature technology of semiconductors and the crucial emerging technology of AI. If Trump doesn’t cancel those programs at Xi Jinping’s behest, they have a good chance of succeeding. The U.S. is ahead in AI so far, and along with its allies (including Taiwan) it maintains a commanding lead in chip technology too.

But those digital technologies are not the only key emerging technologies that will determine national power — and to a lesser degree, economic prosperity — over the next half century. There is also a key nexus of physical technologies that will govern how well countries, companies, and militaries are able to transform software into physical reality. Those technologies are all related to electricity — they include batteries, electric motors, solar power, and various other instruments of electrification. And in pretty much all of these fields, the U.S. and all of its allies are rapidly losing ground to China.

The root cause, I think, is that Americans on both political sides have essentially agreed to frame emerging electrical technologies as being fundamentally about climate change, instead of about national power and prosperity. This is a dangerous misconception. If we don’t stop pigeonholing electrical technology into the climate discourse, it’ll continue to suffer from partisan polarization and misplaced priorities.

Taking Xi Jinping Thought seriously (about electric technology)

Regular readers of this blog will know that I have a pretty low general opinion of Xi Jinping’s personal competence as a leader. His “Xi Jinping Thought”, which he has forcibly inserted into every corner of Chinese society, seems to be mostly a jumble of rambling vague midwittery. But I’ve seen at least one big idea of Xi’s that I think holds some merit — the idea that the world is in the middle of a technological revolution, caused by the simultaneous emergence of a bunch of game-changing technologies.

Tanner Greer has a good blog post explaining this idea:

China’s techno-nationalist drive…is premised on three ideas…The first is that technological and scientific power is the most critical element of national strength and economic growth…The second is that advances in technological and scientific power are not isochronal. Advances occur in sudden leaps and bounds; disproportionate power and wealth go to those who successfully leap first…The final idea, and perhaps the most important, is that we are in the opening stages of the next round of techno-scientific revolution right now.

This is not all about AI…When the Chinese high leadership talks about the coming round of techno-scientific revolution, they mention AI, but only in the context of a long list of promising technologies. These include materials science, genetics and plant breeding, neuroscience, quantum computing, green energy, and aerospace engineering. In Xi’s rhetoric none of these are privileged over the others.

This doesn’t look like a very focused list. In fact, it looks similar to the lists of “critical and emerging technologies” put out by the U.S. government. And that’s fine — it’s smart for a big country like China or the U.S. to focus on a broad range of technologies instead of trying to hyper-specialize.

But at the same time, not every technology is going to contribute equally to national power, and not every technology is currently experiencing a revolution. I think it’s not too hard to write down a short list of “things that suddenly got very good and will obviously be very important”. That list would include:

CRISPR and synthetic biology

Solar power

Batteries

Electric motors

AI

The first of these is important for national power because it can be used to make bioweapons. The second and third are key because they enable energy independence — if you can make a ton of solar panels and batteries, you can power anything you want, and you don’t have to worry about your supplies of fossil fuels being cut off by an enemy’s navy. But the final three of these are especially important because along with semiconductors, they are what allow you to make a drone.

At this point, everyone knows that drones are the future of warfare. Elon Musk talks about this constantly. Whatever the swarm of drones over New Jersey was, it made people realize how fundamentally defenseless they are against this new type of machine. Once drones become autonomous thanks to advances in AI, they will be even more dominant and unstoppable. The shift to drone warfare seems likely to be at least as important as the shift to air power around the time of World War 2, or the shift to precision weaponry in the late Cold War.

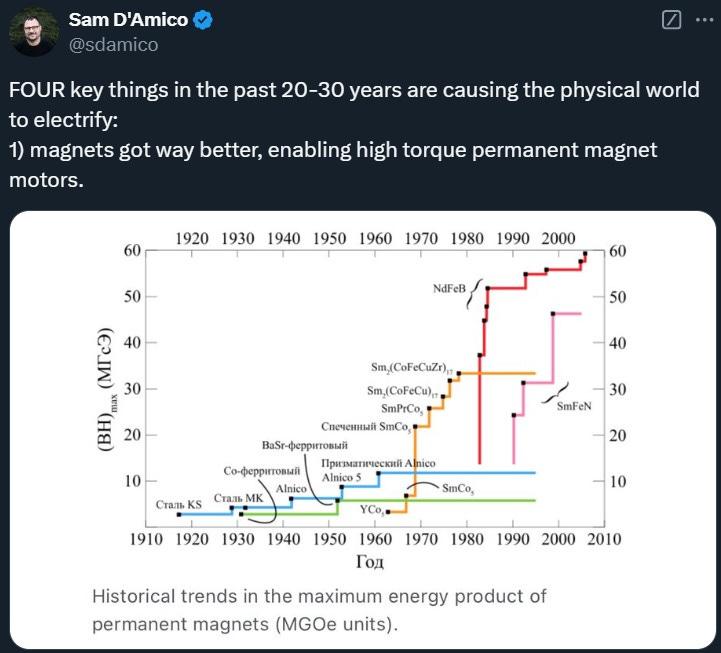

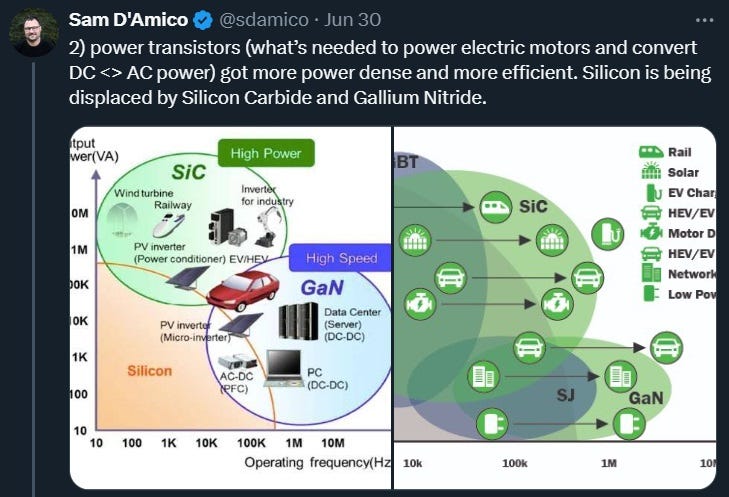

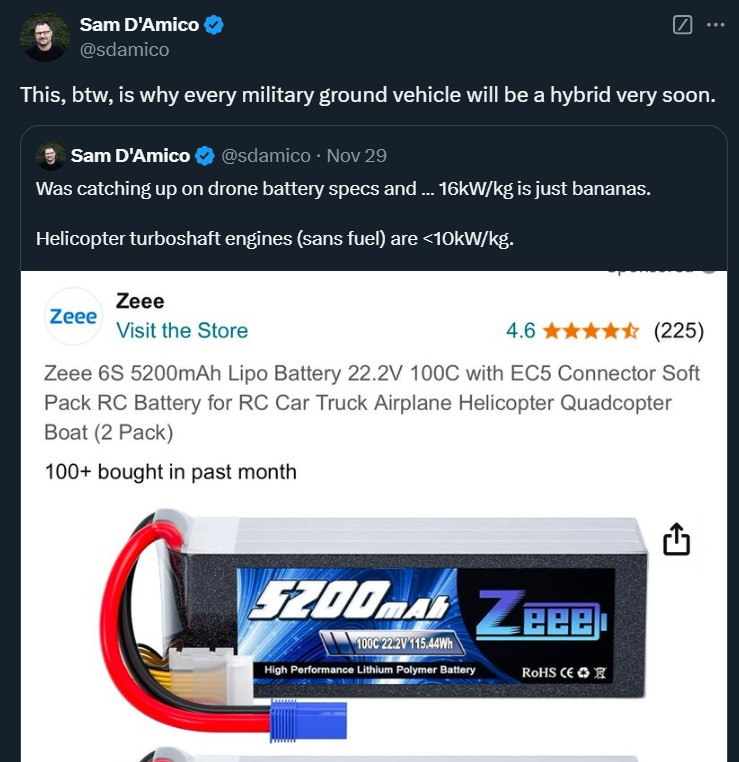

And quadcopter drones emerged thanks to a confluence of rapid technological advances. Sam D’Amico, founder of Impulse Labs, has a good thread in which he explains how sudden advances in magnets and transistors (for motors) and batteries, combined with incremental advances in semiconductors, allowed quadcopters and other electrified technologies to emerge:

Basically, a motor works by turning a magnet, and the stronger the magnet, the harder you can twist it. The fact that we’ve found very strong magnets is one reason it’s so easy to make an electric car that accelerates much faster than an internal combustion car.

The detailed story of how batteries got so good is also very interesting — the technology is a lot more complex than people realize, and there were lots of blind alleys and lucky guesses involved. The always-excellent Brian Potter has a good writeup over at his blog:

In fact, the battery revolution is far from over. A ton of new chemistries for anodes, cathodes, and electrolytes (or solid-state equivalents) are in the pipeline, and if Potter’s history is any guide, the future of batteries will involve a lot of rapid, unpredictable, disruptive shifts.1

In fact, continued battery advances will enable applications that go well beyond little quadcopter drones. Bigger and faster drones will be powered by batteries of course. And with enough energy density and low enough manufacturing costs, even heavy ground vehicles might be electrified:

The more energy-dense (and power-dense)2 our batteries get, and the more torque our electric motors can provide, the closer we get to a future in which combustion itself becomes a relic of the past:

This is a momentous shift. As I explain in that post, for over a century, combustion and electricity existed in a tenuous balance in the human technological arsenal — combustion was for when you needed power and portability, electricity was for when you needed fine control. But the revolutions in batteries and motors are allowing electrical technology to carry around a lot more energy and apply a lot more power. A whole ton of highly refined and specialized combustion-related technologies — like the engines of Japanese cars — might find themselves obsolete over the next few decades.

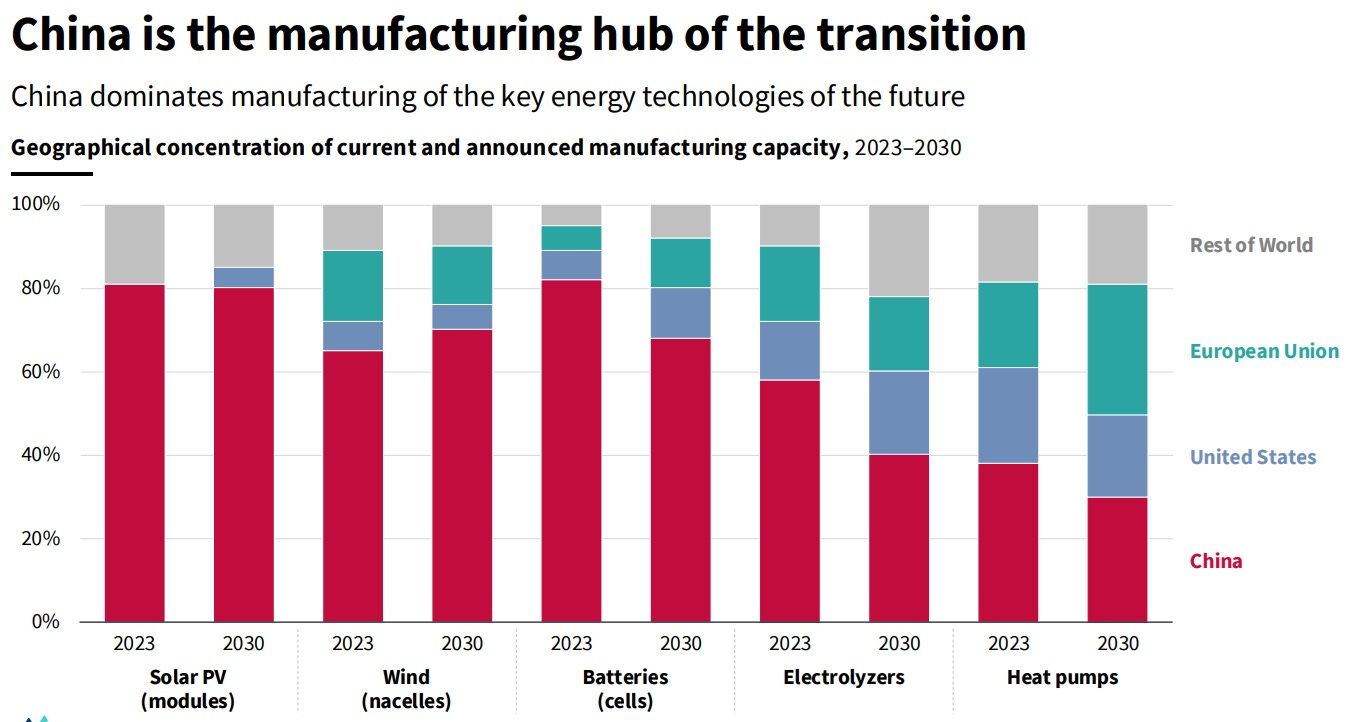

And so far, China — not America or its allies in Asia and Europe — is the country that’s dominating the adoption of new electrical technologies. A recent report by the Rocky Mountain Institute has a bunch of good data. For example, here’s a chart that made a big impression on me:

And here’s a chart for EVs, showing how it’s not even a contest at this point:

And here’s a chart showing the manufacturing gap:

(I haven’t talked much about solar in this post, but it’s an important piece of this too. Solar is incredibly cheap now, and RMI and others have shown that places with a lot of solar have cheap energy for manufacturing. Manufacturing prowess and electrical technology adoption thus feed each other in a virtuous cycle. David Fickling has a fairly good post about how the U.S. lost the chance to become the world’s solar manufacturing powerhouse.)

China’s dominance in these electrical tech sectors is no accident. One of Xi Jinping’s signature policies has been to support the “New Three” industries — electric vehicles, batteries, and solar cells. Tsung Xu explains some of the ways this helped:

A lack of effective policy support for lithium ion batteries in the US meant the industry was dead in the water. Especially for LGAs/states to procure buses/gov vehicles like Shenzhen in the early 2010s as BYD's early customer. China's policy support for LiBs helped them absolutely dominate the existing chemistry leader (nickel based), the current leader (iron phosphate) and future chemistries like manganese in iron phosphate cathode, sodium ion, CATL's "condensed matter" high specific energy, cell to pack and cell to chassis process innovations to increase specific energy and more. Of course their flywheel of EVs pulling demand forward for LiBs helped them dominate on both cost and quality (in terms of defects and pack level energy density).

China's early adoption of EVs and LiBs helped drive an intensely competitive gold rush of new EV makers. Tesla's Model S and eventual GigaShanghai helped too - Nio, Xpeng and Li Auto's founders all test drove and/or did teardowns of the Model S before they founded their startups…This competition forced OEMs to build faster, better, cheaper EVs. Chinese EV companies now take as little as 18 months (!) from napkin to first vehicle delivery, vs Detroit and EU automakers taking 4-5 years. Many companies will die or be acquired, but that is how most disruptive industries with massive and fairly obvious upside start. This competition has been accelerated by policy support for new factory builds, licensing, and production and consumption tax incentives.

One thing he doesn’t mention here is the Chinese government’s support for upstream industries. The materials that go into batteries, electric motors, and solar cells have to be mined and refined. Mining and refining are dirty, low-margin businesses — not the kind of thing that a modern financial system pushes a postindustrial economy toward doing more of. So China’s government leaned against market forces, purposefully dominating the extraction and (more importantly) the processing of many of the key minerals for this industry.

For example, if you look at D’Amico’s chart of magnet chemistries above, you’ll notice the elements neodymium and samarium in the two best types of magnets. China has “an effective monopoly” over processing neodymium, and is the world leader in the mining and processing of samarium. This makes it cheap to build magnets and batteries in China, and it also allows China to use mineral export controls as a weapon — as it recently did with gallium and germanium.

In other words, Xi Jinping Thought is sort of working here. The Chinese Communist Party has deliberately leveraged industrial policies to capture a leading position in a core set of physical technologies that have undergone recent revolutionary changes — batteries, motors, and solar. Assuming it can keep pace in chips and AI, China’s dominance of the new electrical technologies will aid its rise to a position of global hegemony.

The U.S. is stuck in climate debate hell

Meanwhile, the U.S. isn’t just lagging in the race for electrical technology — it’s actively sabotaging itself. The Inflation Reduction Act tried to do for batteries what the CHIPS Act did for semiconductors, and it had some modest success. But Trump promised to repeal it at one point, and some conservatives have made IRA repeal one of their pet causes.

The reason is that Republicans, including Trump, tend to see the IRA as being a climate bill. And who could blame them? That’s exactly how Democrats framed the IRA when it was created, and it’s still how they frame it now. It’s how the mainstream media frames it too. There was also language about energy abundance and job provision, but there was almost no discussions of the national security implications.

There’s a general principle in American politics that anything involving national security will ultimately get at least some bipartisan support, while other issues get relegated to the realm of partisan shouting. Putting electrical technology in the “climate” bucket made the GOP feel safe about the possibility of ignoring or even suppressing it. Had it been framed as a national security policy, it might not be such a tempting target for Trump or the to attack.

I’ve long resisted Matt Yglesias’ thesis that “Climate is the problem”. It seemed to me that since the policy of rapidly deploying batteries and EVs would simultaneously help with a whole bunch of objectives — energy abundance, national security, fighting climate change — that we should just do that policy, and let each person come up with their own reason to support it. But this failed to reckon with how the Republicans would react to the idea that electrical technology is fundamentally part of the climate issue.

The fact is, climate change mitigation is incredibly — almost totemically — unpopular within the GOP and the conservative movement. There is a strong knee-jerk opposition to climate activists, who are generally seen as communists hiding their radical anti-capitalist agenda behind the facade of a global emergency.3 Anything the climate people want, the Republicans will say “no” to.

So when we rhetorically and mentally put electrical technology in the climate bucket, it immediately becomes a non-starter with around half the country. That doesn’t mean it’ll fail — the IRA passed, by one vote — but it’ll be a lot harder to sustain it when the Republicans are eventually elected.

Therefore I think Democrats need to start talking about industries like batteries and EVs not as climate issues, but as issues of national security (and energy abundance). Dems need to remind people in particular that if the U.S. can’t make a battery, China’s drones will be able to overwhelm us in any war. And only industrial policy is likely to be able to avert that outcome.

It would be fairly pathetic if America became a second-rate power in the 21st century simply because we collectively associated the revolutionary technologies of the day with hippies and tree-huggers. The technology of the physical world is being radically transformed, and we need to either harness that transformation for ourselves, or risk going the way of Nissan and Honda.

In fact, I don’t even know if the experimental chemistries that I linked to are the most promising ones. It’s likely that no one does know. As usual, it’s likely we’ll be surprised.

Energy density is about how much total energy you can carry around for a certain weight. Power density is about how much energy release per unit time you can carry around for a certain weight — in other words, how much “oomf” you get for every kilogram of battery.

That perception isn’t entirely false, either — there are definitely some climate activists who are like that.

The Democrats have a pathological inability to frame anything in terms of simple self interest and national pride. They always have to come up with some grandiose moral argument that just makes anyone not already drinking the cool aid gag on the sanctimony.

It's such an easy sell. Why are we electrifying? Because we're going to lead the world in new technology, and we're gonna make a fortune off selling it to the rest of the world! What about the people who work in the oil industry, they're gonna be hurt by this? Nope! They'll be fine. Now that we aren't using the oil at home, we're gonna drill as much as we can and make a fortune exporting that to other countries too. Make America great a̶g̶a̶i̶n̶!

And yet Democrats can't close the deal because their messaging strategy seems to be "how can we make our point in a way that maximizes the number of people that hates us"

No doubt you are right that we face peril in our questionable commitment to these technologies.

And I am sure that the association with hippies and tree huggers contributes significantly to conservative opposition.

But I am pretty sure there's more to the opposition than that.

One huge theme of opposition involves resistance to massive change. Most human beings don't like change, especially change that is forced upon them. And technological advances ALWAYS cause change; revolutionary advances bring about radical change. In the internet era, this is not as vaguely understood as in the past; or, to be more precise, activists with agendas are better able to leverage resistance to change for their own purposes.

When you step away from liberal boiler plate and look at what motivates everyday conservatives, it's the pileup of changes that have occurred during their lives, some very direct (the Pill and its impact on society) and some not-so-direct (electronic media that results in cosmopolitan and rural culture so visible to each other, motivating each to insist on reforming the other... while cosmopolitan culture is tempting rural youth). Meanwhile, good roads allowed the malls to wipe out small town businesses, and then internet businesses to finish the job.

The bottom line is that we face a very difficult dilemma. How to convince a democratic society to choose a massive wave of new technological change.

Yes, framing it as environmentalism hurt. But I wonder whether it would be working regardless. Not without very strong leadership, and I am skeptical that the American public would choose that leadership.

Very depressing.