What if Xi Jinping isn't that competent? (repost)

Plus a new update showing how right I was.

For the record, I would just like to say that I called this one.

In late 2021, I wrote a post arguing that Xi Jinping simply isn’t that competent of a leader, noting a number of areas in which his initiatives seemed to be failing. The piece drew fire from a lot of “China hands” who felt I was straying outside of my lane (which was true), while a number of other people scoffed at the idea that the absolute ruler of an ascendant superpower could be anything other than a genius. Two years later, after Zero Covid, diplomatic blunders, and a real estate crash, my thesis is close to conventional wisdom. In recent weeks, a spate of articles has come out in the Western press blaming Xi for failing to adequately stimulate China’s flagging economy. Xi’s personal objections to welfarism — or to any economic policy he didn’t initially plan for — seem to be a stumbling block. Here’s the WSJ:

[D]espite advice from leading Chinese economists to take bolder action, the people said, senior Chinese officials have been unable to roll out major stimulus or make significant policy changes because they don’t have sufficient authority to do so, with economic decision-making increasingly controlled by Xi himself.

The top leader has shown few signs of worry over the outlook despite the gathering gloom and hasn’t seemed interested in backing more stimulus…The top leader’s apparent reluctance to embrace such moves, which people familiar with the matter say is partly rooted in his ideological preference for austerity, is alarming [the] public.

And here’s CNBC:

Most, though not all, China watchers point to Xi himself as the instigator of those recent [policy] changes. While policy wonks split hairs over whether the U.S. and its allies are “decoupling” or “derisking” from China, [veteran China watcher Orville] Schell says “the real decoupler is Xi Jinping.”…Ryan Hass, director of the China Center at Brookings, cites Xi’s “ideological rigidity and lust for control” which “is at odds with the pragmatism that defined China’s period of reform and opening.”

Meanwhile, there’s another set of stories about how Xi is growing increasingly paranoid, and causing turmoil in China’s leadership with a series of purges of his own hand-picked officials. Here are some excerpts from a Bloomberg writeup:

Xi’s mysterious purge of his foreign minister in July, followed by the reported ouster of his defense chief less than two months later, is making China appear unstable to the outside world. The Chinese leader also overhauled the generals overseeing China’s Rocket Force, which manages the nation’s nuclear arsenal, without giving an explanation…

“These men were handpicked by Xi himself for promotion,” [researcher Richard] McGregor said. “So their fall reflects on him.”…

As Xi’s mistrust of his officials grows, the system is showing signs of becoming paralyzed as he tries to micromanage domestic operations. One foreign executive in Beijing, who asked not to be identified, said Chinese officials now operate in “silos of fear,” with everyone scared of Xi and also isolated from each other.

There’s also a fun anecdote about Xi replacing every single object in his hotel room in Sudan with replacements flown in from China. It’s not clear whether this represents the beginning of a spiral into Stalin-like paranoia, but the signs certainly do not seem auspicious.

None of this is particularly surprising to me. I am no China expert, but Xi’s personality is fairly plain to see. He’s the kind of leader who excels at entering and dominating a large existing organization through relentless placement of loyalists in key positions. Once that kind of leader achieves absolute dominance of his organization, he often starts purging his own loyalists, because they’re the only ones who are available to purge.

Xi is also clearly the kind of Boomer conservative whose understanding of economics is heavily tinged with industrial nostalgia and strange notions of masculinity. That’s not a sound basis for making economic policy, and so policy mistakes like fiscal austerity in the middle of a financial crisis are only to be expected.

Of course many of the “China hands” also saw these signs and made these calculations, far earlier than I did. But few could say it out loud, since they either had to stay on China’s good side, or wanted to preserve U.S.-China commercial ties, or simply didn’t want to be too bold or aggressive in their writings. The task of saying publicly what other people had only privately discussed thus fell to your friendly neighborhood econ blogger, Yours Truly.

Anyway, I am a bit behind on writing this week, since my disabled rabbit just came home from the vet where he was getting rehab for his herniated disc, and caring for him has taken quite a lot of time. In the meantime, here’s the post where I anticipated the tarnishing of Xi’s previously sterling reputation as a leader.

Xi Jinping is widely hailed as China’s most powerful leader since Mao. He certainly has been highly effective at consolidating power under his own person. From his utter destruction of potential rivals Bo Xilai and Zhou Yongkang to a sweeping “anti-corruption” campaign that purged or cowed every faction but his own, Xi showed very quickly that he was not going to tolerate the factional pluralism that the Chinese Communist Party had enjoyed under his predecessors. His abolition of term limits essentially means that he’s now president for life, effectively ending the system that had seen three peaceful transfers of executive power. And he has been more effective than any leader since Mao at creating a cult of personality around himself, recently introducing “Xi Jinping Thought” into school curricula. Now, at the Communist Party plenum, he’s expected to push through a resolution — only the third in the party’s history — devoted to celebrating his own personal accomplishments. State media’s official communications have begun to take on a tone of adulation that would make video game script writers blush:

But other than turning a bureaucratic oligarchy into a personalistic dictatorship, what are Xi’s accomplishments, exactly? In my experience, people tend to assume that Xi is hyper-competent because:

There’s a general impression that the Chinese government is hyper-competent, and Xi has made himself synonymous with the Chinese government, and

Under Xi’s watch, China has arguably become the world’s most powerful country.

But this doesn’t mean Xi actually deserves his reputation as a one-man engine of Chinese greatness. Much of his apparent success was actually inherited from his predecessors. He has taken absolute control of the apparatus built by people such as Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin, and Hu Jintao, but I think it’s hard to argue that he has added much to that apparatus.

In fact, I think there are multiple signs that Xi has actually weakened the capabilities of the Chinese juggernaut. So far, China’s power and general effectiveness are so great that these signs seem to have gone largely unnoticed, but I think they’re there. The three big ones are: Slowing growth, an international backlash against China, and missteps related to the Covid pandemic.

It’s time to consider the possibility that for all his self-aggrandizement, Xi Jinping is just not that competent of a leader.

Slowing growth

Xi Jinping took power at the end of 2012. By then, China was already undergoing a growth slowdown; GDP increases that had been in the 10% range for decades fell to somewhere between 6.5% and 5%, depending on whether you believe China’s own statistics or those gathered by independent agencies. Let’s give China the benefit of the doubt and use the official government numbers:

It’s still clear that things are trending downward, Covid aside, and it’s not clear where the decline will stop; for reference, developed countries generally grow around 2-2.5%. Once China hits that level and stays there, its catch-up growth is basically over.

So Xi presided over the end of China’s hypergrowth. To some extent this is not his fault. No country can grow at 10% forever, and there were many structural forces pushing downward on China’s numbers — the end of the demographic dividend, the exhaustion of rural surplus labor (the Lewis Turning Point), the saturation of export markets, and so on. But China is also slowing down earlier than South Korea, Taiwan, or Japan did in their day. China’s per capita GDP (at PPP) is still only about 1/3 that of a developed country, so if they stop catching up at about half of developed-country levels, that will not be a great showing.

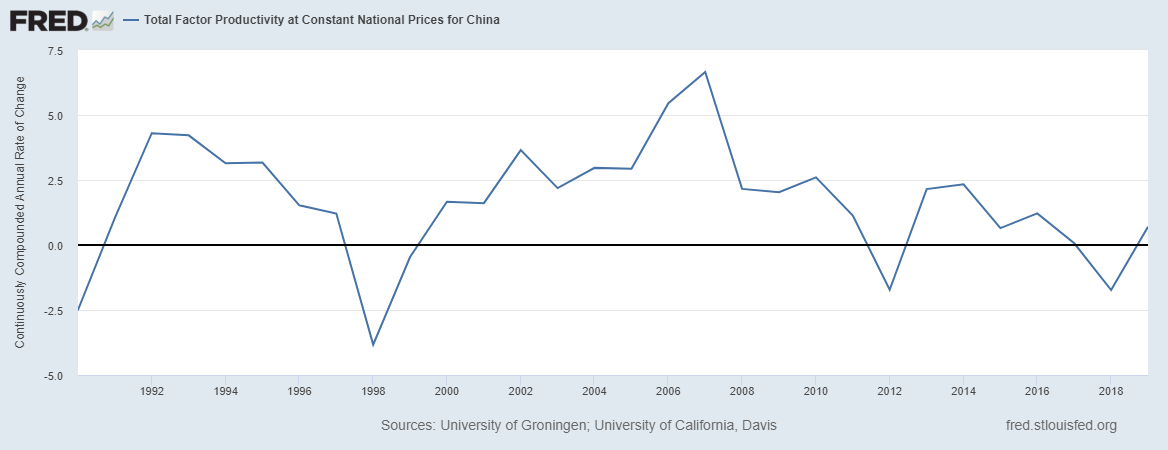

Why is China slowing down? Part of it is inherent to China’s growth model, which Xi inherited from his predecessors Jiang and Hu. As Michael Pettis will be happy to tell you, China’s growth has been unusually investment-heavy, even when compared to South Korea and Japan. Much of that investment has gone into real estate and infrastructure, leaving China’s economy unusually dependent on real estate. In fact, every time China has faced a macroeconomic challenge over the past few decades, its response has been to funnel money to real estate and related industries, usually through state-controlled bank loans to low-productivity state-owned enterprises. The result of that has been that total factor productivity growth has slowed to a crawl, or possibly even come to a stop since Xi took power:

Now again, Xi did inherit this growth model from his predecessors. And as Xi is now discovering with the Evergrande crash, this is a very difficult treadmill to get off.

But if Xi didn’t create China’s economic dilemma, he didn’t do much to fix it either. This is the 7th year of Xi’s rule, and he didn’t really seem to take the real estate problem particularly seriously until recently. In 2014, China reflated real estate when a property crash seemed to loom. In 2015-16, when a stock market crash and capital flight threatened the economy, it was once again real estate to the rescue. For all the talk of a state-driven “profound transformation” of China’s economy, Xi has spent much of his time until now kicking the can down the road. In fact, this is a general pattern with Xi; back in the summer, Daniel H. Rosen of Rhodium Group wrote out a long litany of hesitant, half-cocked reform efforts Xi has undertaken, only to reverse course each time.

Xi has also reversed Deng and Jiang’s pattern of reforming state-owned enterprises and encouraging private-sector growth. Even before the recent crackdowns on the internet industry and other disfavored sectors, Xi had been emphasizing a greater role for SOEs despite their spotty record on productivity. Of course it’s possible that this time is different, and Xi’s focus on SOEs really will inaugurate a new and better kind of capitalism (and there is no shortage of theories about how that might work). But if the gambit fails, Xi is going to have to take a hefty share of the blame for that.

Another problem with Xi’s reliance on SOEs is that it sets off alarm bells in other countries, who view state-backed competition as an unfair advantage. That will increase the likelihood of trade wars, including measures like the export controls that have wounded national champion Huawei.

As for Xi’s big push for dominance in the semiconductor industry, it has yet to play out — there have been plenty of high-profile failures and setbacks, but it’s too early to tell.

Meanwhile, there’s the strong possibility that Xi’s crackdown on industries he doesn’t like will turn out to have been a mistake. Barry Naughton, one of the keenest observers of China’s industrial policies, sees these moves as “hasty and ill-conceived”. Instead of squeezing investment and talent away from finance and consumer internet and toward semiconductors and electric cars like a big tube of toothpaste, the crackdown might simply chill private appetites for risk, forcing yet more reliance on the state sector.

(Finally, there are Xi’s economic missteps related to Covid and the supply chain disruption, but I’ll leave those for the third section.)

Overall, Xi’s approach to the economy looks an awful lot like a kid playing with toys — smashing the ones he doesn’t like, telling his favored champions to go forth and conquer. If that approach works, it’ll be because the corporate and technological systems built during the Deng, Jiang, and Hu periods are just so robust that they can basically accomplish whatever Xi tells them to do.

International anger and fear

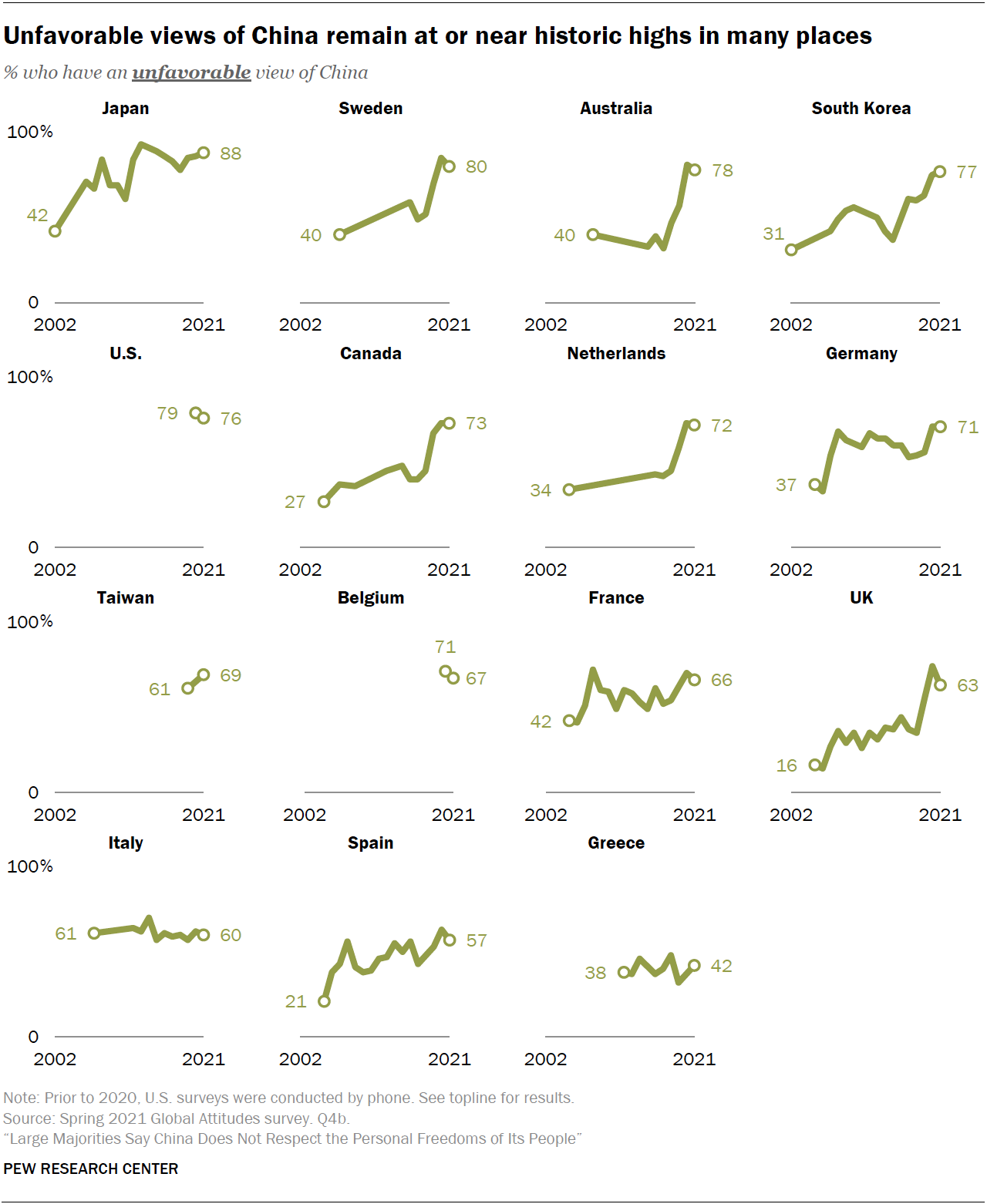

If the jury is still out on Xi’s economic approach, it’s already clear that diplomatically, he has put China in a worse position. The country’s de facto alliance with Russia — nurtured mostly during Hu’s tenure in office — still holds, and Pakistan, North Korea, and Cambodia remain dependent on Chinese protection and largesse. But as a result of Xi’s swaggering, bellicose approach, other countries in China’s neighborhood have increasingly hardened their attitudes against a superpower they once considered a potential partner.

Xi’s pressure on Southeast Asian nations over control of the South China Sea has led to strong negative attitudes toward China in Vietnam, the Philippines, Indonesia, and other countries. But the biggest diplomatic loss might be India, the only other nation that rivals China in size. India is a member of the China-led Shanghai Cooperation Organization, along with Russia and Pakistan, so it looked as if it was edging closer to China. That changed in 2020 when Xi’s troops bloodied India’s nose at a border battle along their disputed border. Now India is moving decisively toward a de facto alliance with the U.S., joining a new, upgraded version of the Quad and deepening cooperation in other ways. As in other Asian countries, Indian public opinion has become sharply more anti-China.

These are all unforced errors on Xi’s part. Why alienate India? Why push against Southeast Asian countries? Perhaps it was necessary for China to oppose Japan and the U.S. in order to complete its ascent to superpower status and avenge historical humiliations, but why did Xi choose to slap otherwise neutral or even friendly nations in the face?

Then there’s the case of Belt and Road. Xi’s big plan to build infrastructure in other nations in order to secure diplomatic fealty, access to natural resources, and pork for Chinese companies ended up being mostly a debacle. From a port in Sri Lanka to rail projects in Africa to a whole host of projects in Malaysia, partner countries found themselves owing money to China without reaping the promised economic benefits. Even in China’s faithful ally Pakistan, things didn’t work out so well. The whole project is losing momentum as opposition mounts and more economically well-thought-out competition from rivals intensifies, leaving bad feelings in its wake.

Meanwhile, Xi has done a number of other things to alienate potential friends and to harden attitudes against him in third-party observers. His “wolf warrior” diplomacy — basically turning the Chinese diplomatic corps into swaggering, bellicose bullies — has backfired spectacularly, giving China a bad reputation around the world. Xi decided to abandon his predecessor’s policy of mostly leaving Hong Kong alone, and crush the city’s resistance with a draconian new national security law that jailed dissidents and is dismantling much of the island’s beloved pop culture. And Xi’s heavy-handed approach toward the Uyghurs, throwing huge numbers of innocents into camps to be abused and even tortured, and turning the rest of Xinjiang province into an open-air prison with high-tech surveillance, has given China the image of a totalitarian state right out of the worst days of the 20th century.

Finally, Xi’s crackdown on video games, LGBT people, pop culture fandoms, and other freedoms has reinforced the country’s totalitarian reputation.

As a result of all this, China is now regarded very negatively around the developed world as well as in Asia.

Again, these are unforced errors. Xi didn’t have to crush Hong Kong; doing so has neither increased China’s security nor provided it with any tangible economic benefit. Xi didn’t have to tell his diplomats to do their best impression of Kaiser Wilhelm II. Nor will cracking down on gays and video games accomplish anything except to make China look like some kind of cartoon villain.

The impression, as with the economy, is one of boundless confidence and swagger — a man convinced that China is so strong and so ascendant that because he controls China, he can push around the rest of the world at will. The result looks like it could be the hardening of a coalition to contain China — something that, under Hu Jintao, looked like it might never happen.

Covid missteps

Finally, we come to Covid. Let’s put aside China’s role in actually unleashing the virus upon the world — that debate is highly contentious and not likely to be resolved soon. The fact is, Xi’s government has made a number of other missteps related to the pandemic.

First, there’s China’s “zero Covid” policy. During the early months of Covid, when the virus still had an r_0 of 3, it was possible to stamp out the virus through purely non-pharmaceutical interventions — and China, like some other countries, managed to do this. But the government apparently bragged about its success so much that when the much more infectious Delta variant began to spread, Xi and his people felt that they would lose face if they changed to a “live with Covid” strategy as countries like South Korea have. So China continues its ever more manic efforts to eliminate a virus that is now probably too infectious to be eliminated. And this is hurting the economy, even as China’s rivals recover. And that is contributing to social unrest.

Of course, living with Covid is a lot easier if you have access to good vaccines. China, unfortunately, does not. Xi’s government decided early on to engage in “vaccine diplomacy” to gain international influence at the expense of the U.S. For a while, Xi’'s people even tried to spread rumors that U.S.-made mRNA vaccines killed people. The only problem is that China’s homemade vaccines are less effective than the U.S.-made ones. Unable to simply buy from Pfizer without losing face, China is now racing to develop its own homegrown mRNA vaccines — essentially, to reinvent the wheel — while its economy falters.

Also hurting China’s economy is a power crunch. This is generally blamed on the country’s rigid energy pricing system, which doesn’t allow producers to pass higher costs on to consumers. (Xi should have fixed that years ago, but of course so should his predecessors.) But instead of deregulating to allow prices to rise like Jimmy Carter did when faced with a similar problem in the 70s, Xi is going to ramp up imports and production of coal, basically scotching his country’s commitment to decarbonization in the short term.

And of course Xi’s various crackdowns may be contributing to China’s current slowdown as well.

As with longer-term issues, it’s possible to see China’s post-Covid economic woes as the result of a swaggering overconfidence at the top. It’s perfectly fine to bamboozle foreign investors by telling them that the Chinese government is economically and epidemiologically omnipotent. But Xi appears to have gotten a little bit high on his own supply.

Stuck with Xi

The problem with Xi is that if he is actually far less competent than people seem to believe, there’s not much China can do about it. Xi’s second term as President will be up in early 2023, but he eliminated term limits, so he’s essentially supreme-dictator-for-life. At 68, he probably has another decade left in him. As Mao, Stalin, and many other dictators-for-life have shown, a long term in office tends to magnify the worst characteristics of an autocrat. Does anyone think Xi will step down voluntarily to let someone younger take the helm?

If other Chinese leaders are starting to wonder about Xi’s competence, they’re certainly not speaking up; after seeing what happened to Bo Xilai, who would? And the Western press still seems to view Xi as simply the personification of a hyper-competent, triumphant Chinese state (which is perhaps not too far from how he sees himself). But if growth keeps slowing, big plans keep fizzling, and bellicosity and cruelty keep backfiring, I wonder how long it will be before people both inside and outside China start to question the narrative.

And as a final word, seeing Xi’s stumbles really drives home how hard it is to be a truly successful autocrat. Their human rights records are certainly nothing to admire, but people like Deng Xiaoping and Park Chung-Hee — dictators who can take personalistic control of a country and leave it much stronger than they found it — are rare. Ultimately, that’s why autocracy is not a good way to organize a society — you have to roll the dice and win every time a truly strong leader comes to power. If Xi screws up the legacy his predecessors left him, it’ll be his fault, but it’ll also show that China’s political system wasn’t as ironclad as many have let themselves believe.

I would retitle your essay:

XI Makes Sense to XI

One important thing I think you left out of your analysis of XI is his obsession over why and how the Soviet Union fell. He believes that they lost their ideological commitment—but it was their nationalist ideology rather than their communist ideology. He sees the focus of the individual Chinese on their own economic welfare as so much attention subtracted from the nation's collective welfare--on Great China.

One reason why he feels affinity with Putin is that Putin has restored the primacy of Great Russia in the Russian mind, thereby reversing in a large degree the fall of the Soviet Union.

XI believes that the people of China have as much welfare as they need— in fact the populace should head toward belt tightening rather than the pursuit of a higher standard of living. At the same time, they should remember the truly poor among them and be glad to watch while the poor catch up with the median Chinese in a move XI calls "common prosperity."

XI is clearly determined to swim against market forces.

That is why XI shows no interest in bailing out the average Chinese or losses in the real estate market or in economic stimulus. Xi thinks the average Chinese has more than enough of this world's goods already.

This is a major reason why I think XI will never invade Taiwan. He doesn't respect or trust the Chinese people to have the intestinal fortitude to get the job done. In XI's mind, two decades of excess prosperity have made them — gasp! — decadent.

Finally, in adopting a posture of swaggering strength on the world stage —suppressing Hong Kong, wolf diplomacy — he wanted to show that China was finally post-colonial and could walk with its head as high as the US or Britain ever did. in fact, XI's invasion of Hong Kong was the final act in the reconquest of that bit of Chinese territory from British colonialism. He may have thought that China's swaggering attitude might actually be attractive to other post-colonial nations. It worked for Donald Trump. In fact, China’s swagger would have attracted other nations as cowed suppliants if there had not been another 800 pound gorilla in the world in whose shadow they could take refuge—the United States.

Note to readers: if you like if you're interested in my take on China, please subscribe to my substack because there will be more posts on China forthcoming.

https://kathleenweber.substack.com/

Surprised by comments here defending Chinese growth. Covered well in the post, and demographic outlook alone is enough to continue dropping the growth rate. As others have said, like Putin, Xi has a ‘historic’ vision of China and its ideology and would rather stick to that and sacrifice growth. Both men are old and leading decaying empires, one at the end of decay and the other at the beginning. In their old eyes, who cares about growth? It’s about preserving some historical vision of the country in amber. Ironically it’s the strong armed attempt to do so that will make sure it doesn’t happen.