EVs are just going to win

Because they're a superior technology, and superior technologies win.

My last post was pretty dark and dire, so here’s something a little more cheerful and optimistic. One of the most important and positive trends that I’ve been trying to highlight over the past few years is the amazing progress in battery technology. Huge increases in energy density and even bigger declines in manufacturing costs have made batteries competitive with combustion engines for a large variety of applications. The most important of these is transportation.

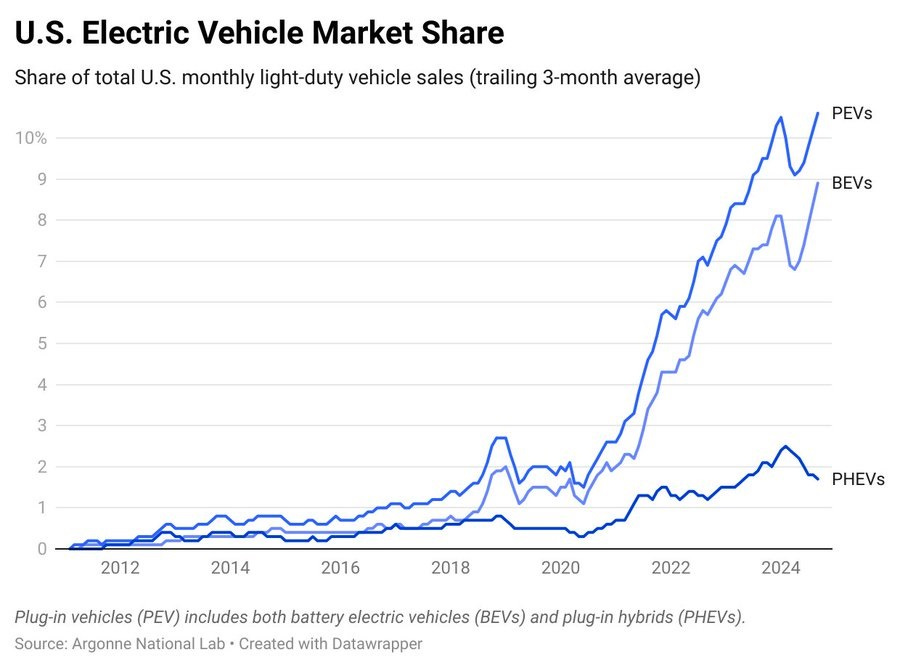

At the beginning of this year, the big story about electric vehicles was that sales were slowing down. Detractors of EVs — and there are a lot of them out there — declared that EVs are a flash in the pan, that interest is already waning, that the problems of EVs would prevent them from ever displacing internal combustion cars, that EVs will never be viable without subsidies, and so on. Essentially, the story was that the EV revolution was over, or at least stalled indefinitely.

That narrative has now essentially collapsed. EV sales reaccelerated in the U.S. after just a couple of months, and their market share has hit a new record high:

And EVs continue to outsell combustion cars:

Nor is there any sign of a slowdown at the global level:

A number of developing countries are seeing truly spectacular growth in EV sales:

So EVs are still winning. But they haven’t won yet; only 4% of the global passenger car fleet, 23% of the bus fleet, and less than 1% of delivery trucks are electrified.

But at this point I think the writing is on the wall. The phenomenon of a superior technology displacing an older, inferior technology is not uncommon, and it generally looks like the EV transition is looking now. When a new technology passes a 5% adoption rate, it almost never turns out to be inferior to what came before; with EVs, that threshold has now been reached in dozens of countries.

In fact, we don’t have to rely on trend-based forecasting to understand why EVs are just going to win. There are a number of fundamental factors that make EVs simply better than combustion vehicles. The longer time goes on, the more these inherent advantages will make themselves felt in the market.

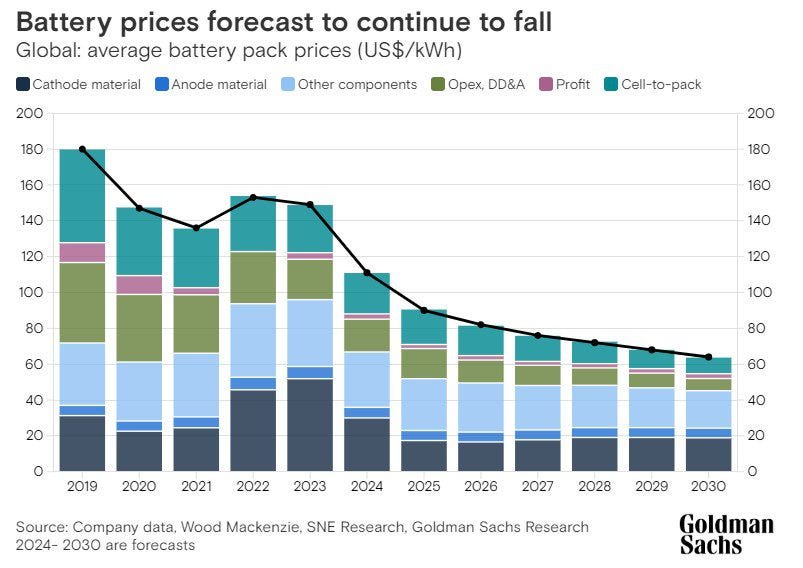

The first of these is price. Currently, EVs often require government subsidies in order to be price-competitive with combustion cars. But batteries are getting cheaper and cheaper as we get better and better at building them. The cheaper batteries get, the smaller the subsidies required to get people to switch to EVs. Goldman Sachs reports that this crucial tipping point will be reached in about two years:

Technological advances designed to increase battery energy density, combined with a drop in green metal prices, are expected to push battery prices lower than previously expected, according to a new briefing from Goldman Sachs Research…

Goldman Sachs’ researchers further predict that average battery prices could fall as far as $80/kWh by 2026, which would equate to a drop of almost 50 per cent from 2023 levels.

It is at this point that the investment giant expects battery electric vehicles could potentially achieve cost parity with ICE vehicles in the United States on an unsubsidised basis.

Once batteries cross that tipping point, the EV revolution will take on its own momentum. It will simply be cheaper to buy an EV than a combustion car. People will gravitate toward the cheaper option, especially if it comes with other advantages. And in this case it does.

EVs’ second advantage is convenience. Most EV owners will almost never have to fill their cars up at a station. This is because they will charge their cars at night, in their own home garages or driveway.

The BYD Atto 3 has a range of 260 miles. Suppose you only charge your Atto 3 halfway every night, to preserve the battery life (just as you would for your phone). That’s 130 miles. And let’s say that just to be on the safe side, you’d stop driving at 100 miles a day.

Very few Americans drive their cars for more than 100 miles a day! The number is less than 1%. In fact, the average miles driven per day is around 40. Which means that as an EV owner, on all those days when you don’t drive over 100 miles, you will never have to visit a charging station at all, any more than you now visit charging stations for your phone.

I suspect that many Americans still don’t understand this basic fact about EVs. They’ve spent their entire adult lives periodically visiting gas stations to fill up, so they naturally imagine that they’ll be doing something similar with an EV — visiting a charging station whenever their batteries get low. But that’s not how EVs work at all! They’re more like a phone than a car — you plug them in at home, so you almost never have to charge them when you’re out and about.

Of course, this doesn’t work for everyone, because not everyone has a place to charge their car at home. If you use street parking instead of a driveway or garage, it’ll be a lot harder for you to own an EV. But fewer than 10% of Americans park on the street when they’re at home. If you live in an apartment complex, that complex will eventually have EV chargers in most or all of the spaces in its parking lot, especially as EV adoption increases.

This means that simply comparing how long it takes to charge an EV vs. how long it takes to fill up a combustion car’s gas tank makes absolutely no sense. With a combustion car, you’ll be going to the gas station about once a week, spending about 8 minutes there each time. With an EV, it’ll take 30-40 minutes at a station to charge your car fully, but you’ll almost never go to a station. You’ll only go when you’re on a road trip or on those very rare days when you need to drive more than 100 miles in a day. So the proper comparison of filling times is “eight minutes every week, or 30-40 minutes on very rare occasions”. The latter is just much more convenient.

EVs’ third big advantage is that they require much less maintenance than combustion cars. A combustion car has a complicated engine with a lot of moving parts, all of which can break down. An EV is much more simple, getting its energy directly from the battery with far less machinery in between. A simpler car means fewer parts to break down. That’s why EV maintenance costs are 50% lower than combustion cars.

EVs’ fourth advantage is faster acceleration. Acceleration is one of the things people enjoy the most about driving cars, and EVs just completely destroy combustion cars here. A battery-powered electric motor can start accelerating your car with maximum force pretty much instantaneously, as soon as you hit the pedal. A combustion car has to burn gasoline and turn a bunch of gears before the acceleration can begin. Thus, EVs will always be able to go from 0 to 60 faster than combustion cars.

EVs’ fifth advantage is quiet. Combustion cars make a lot of noise, with that controlled explosion and all of those moving parts. EVs are incredibly quiet, since all they’re doing is pushing electrons through a wire. This is why EVs are far, far quieter than combustion cars.1 That’s helpful for when you’re driving and want to listen to music or a podcast. It’s also nice for the neighborhood around you — the fewer growling, roaring combustion cars there are on the streets, the more peace and quiet we all get.

That’s a huge suite of technological advantages for EVs. What advantages do ICE cars still have? Combustion cars’ range advantage has basically evaporated, with plenty of EVs having ranges of over 300 miles. Their slight remaining cost advantage is about to become a cost disadvantage in a couple of years, even without subsidies. Their quicker fill-up time almost never comes into play, since EV owners rarely have to fill up.

Other than the familiarity born of long use, I don’t see many significant, enduring advantages for combustion cars over EVs. And as EVs become more popular, combustion cars will become less and less convenient, because of a doom loop. In a post a year ago, I tried to explain why:

[T]he more gas stations there are, the more convenient it is to drive, and the more people drive, the more profitable it is to run a gas station. This is why we have a lot of cars and a lot of gas stations; they reinforce each other.

By taking internal combustion traffic off the road, EVs are going to make gas stations less profitable to run. Gas stations have fixed costs that they need to make up for by catering to large volumes of customers; when they can cater to fewer customers, their fixed costs are harder to pay, and some go out of business (or switch entirely to EV charging stations). When the number of gasoline-powered cars on the road goes down by double-digit percentages, it’s going to lead to a lot of closures or conversions.

When some gas stations vanish, it makes it harder to drive an internal combustion car as your primary mode of transport. This is because gas stations are fewer and farther between. This creates range anxiety if you’re on a long trip, but it also just forces you to drive farther and every time you fill up. That gives people an incentive to switch to an electric.

Note that this network effect is yet another subtle advantage of EVs over combustion cars. Combustion cars rely on a nationwide network of gas stations in order to be usable. But EVs almost always charge at home, so they rely much less on having a network of charging stations.

So EVs are just a superior technology to combustion cars. They’re soon to be cheaper, they’re more convenient, they’re much easier to maintain, they’re more powerful and far more silent. They will mostly replace combustion vehicles; it’s just a matter of when.

American industry needs to realize this fact. Right now, Chinese auto companies have been far more aggressive than their established rivals in terms of switching to EV technology. Bloomberg’s Gabrielle Coppola and Danny Lee have an excellent, sobering feature on the rise of China’s electric auto champion BYD:

Now executives from Detroit to Tokyo have to figure out how to compete with BYD, and they know tariffs alone won’t cut it. For years, they couldn’t or wouldn’t make the case for cannibalizing profitable business with an expensive, technologically novel experiment such as the electric vehicle, and now it’s unclear if they’ll ever catch up. The Alliance for American Manufacturing (AAM), a lobbying group representing American companies and labor groups, has called China’s EV offensive “an extinction-level event” for the American auto industry. They realize BYD has built EVs that many Americans, starved for an affordable option, would probably be happy to buy.

Tesla was America’s answer to BYD — indeed, it did more than BYD to pioneer many of the key technologies in the EV revolution, and to drive down their costs in the 2010s. It’s still (just barely) the world’s top electric car seller. But in the last year or two, Tesla has stumbled, losing some EV market share to old-line auto companies in the U.S. domestic market, and facing an increasingly uphill battle against domestic champions in China. Hopefully Tesla will recover its footing, but even if so, the U.S. needs more than one EV champion.

But even though the U.S. has lagged, the EV revolution is a great thing for the world. In addition to benefitting consumers directly by giving them better cars to drive, the ascendance of EVs will also help the world mitigate climate change. It’s definitely a reason for optimism in these troubled times.

Update: In the comments, Matt Yglesias writes:

This strikes me as in some ways less a contrast to yesterday’s gloomy post about autocratic takeover than a complement to it.

As you note at the end, the EVs that are “going to win” are Chinese EVs. America is going to face pressure to stall the EV transition to prop up our auto industry, lose export markets anyway, and have our top domestic automaker be Tesla whose CEO is deeply embedded in the global autocratic axis. I’m glad the new cars are less polluting! But this still seems like part of the story of the rise of the Chinese century.

I’m very concerned about the global triumph of totalitarianism, but I’m not concerned about EVs making the problem worse. You could make a case that some new technologies inherently benefit totalitarians, like smartphones and apps that allow the government to monitor people’s movements and control their speech. But I don’t think EVs are one of these; there’s nothing about a battery and an electric motor that inherently privilege repressive regimes. The fact that China is currently better at making EVs is a function of the fact that their system is currently better at making a lot of different goods in high volumes for low prices. They’re also better at making desk lamps. If EVs are “part of the story of the rise of the Chinese century”, then so are desk lamps.

In any case, the rise of EVs means that people get cars that work much better, while also being better for the environment. It’s hard for me to sit around feeling bad about that just because China is a big, powerful country who makes a lot of cars.

They’re so quiet, in fact, that they have to add back in a little noise just so pedestrians know they’re coming

This strikes me as in some ways less a contrast to yesterday’s gloomy post about autocratic takeover than a complement to it.

As you note at the end, the EVs that are “going to win” are Chinese EVs. America is going to face pressure to stall the EV transition to prop up our auto industry, lose export markets anyway, and have our top domestic automaker be Tesla whose CEO is deeply embedded in the global autocratic axis. I’m glad the new cars are less polluting! But this still seems like part of the story of the rise of the Chinese century.

Even if you make just one or two longer trips per month, it still doesn't make much sense for many to own an EV.

I live in a big European country that is much more densely populated than the US. You can arrive anywhere with a 500km trip.

I have to make a 500km trip about once a month, and it obviously I would never, never use an EV to do it. Refilling gas is super-fast on the highway and it takes like 2-3 minutes, and then you can go.

With a tesla model 3, at highway speeds, when it is cold (from what i can see online) you can maybe do around 250km, for me it would mean one complete charge and a bit more to make the last few km, or like two 80-85% and a last shorter charge for the last few km. Assuming that I'm starting the trip at 100% charge. If I'm correct it would add like at least 45 minutes to the trip, likely some more.

On a 3.30 trip it doesn't make much sense honestly.

It would be better in the summer or when it's warmer, but for some few months it would be like that.

And this is a best case scenario with a really good EV that has an extremely fast charging speed and a good price for what you get. At least in europe 95% of the alternatives are far worse in one or all the categories mentioned above.

The newly announced renault 5 base price is 35.7k and has a max charging speed of 100kw and a smaller range.

A much, much bigger problem here in europe is that there are a ton more people that live in condos and have no way to charge it at home, compared to the US, and the vast majority of them park in the streets (me and my family included, but again, the average person doesn't have a garage). And there are exactly zero chances that charging stations will be built on sidewalks. Not only it would be extremely impractical (1) sidewalk are often really narrow, 2) do you reserve half the sidewalk "spots" for EVs when there are still hundreds of millions of petrol cars? 3) the cost of that?), it would also be a nightmare from a logistical point of view.

The best of both worlds is by far PHEV for the foreseeable future, where you can get much of the advantages of the EV but still aren't forced to hunt for a charging station, or wait long times to "fill the tank".

I disagree that price is the only problem: for first, I've seen a ton of forecasts about incredible adoption rates for EVs ten years ago that didn't pan out, along with forecasts of "this will be cheaper in 2025" that really never materialized.

And second, the charging problem is a real one: I think that we need better battery technology. Some startups are promising C/3 discharge rates and 70-100% better battery density. That would be game-changing. At that point you could really charge it weekly at a supercharger-like station for like 5 minutes to fill half of the "tank", and you'd solve the chargning problem for like 98% of people.

There is no doubt that one day EVs will be the obvious choice for everyone, but I think the super-hyped EV enthusiasts need to assess the issue more realistically and don't assume that pointing out flaws is because "uh conservatives" or "uh did you run the math??" (not talking about you in particular).