A Nobel for the big big questions

Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson win a prize for their grand unified theory of development.

Every year when they award the Econ Nobel Prize, I do a post about it. I wrote posts about Goldin in 2023, Bernanke, Diamond, & Dybvig in 2022, and Card, Angrist, & Imbens in 2021. But I almost didn’t do a post this, year, because I’m not actually that happy about this year’s prize, and I don’t like to be a party pooper. But I suppose that carping about mainstream macroeconomics used to be my brand as a blogger, so I might as well return to my roots.

Long-time readers will know that I don’t think much of Nobel Prizes in general. They elevate individual contributions way too much, when most big discoveries are big group efforts and/or series of small incremental additions. This creates a “cult of genius” that doesn’t reflect how science really works, and creates too large of a status distinction between prizewinners and others.

On top of that, I also have some additional criticisms of the Econ Nobel.1 The science prizes rely very heavily on external validity to determine who gets the prize — your theory or your invention has to work, basically. If it doesn’t, you can be the biggest genius in the world, but you’ll never get a Nobel. The physicist Ed Witten won a Fields Medal, which is even harder to get than a Nobel, for the math he invented for string theory. But he’ll almost certainly never get a Physics Nobel, because string theory can’t be empirically tested.

The Econ Nobel is different. Traditionally, it’s given to economists whose ideas are most influential within the economics profession. If a whole bunch of other economists do research that follows up on your research, or which uses theoretical or empirical techniques you pioneered, you get an Econ Nobel. Your theory doesn’t have to be validated, your specific empirical findings can already have been overturned by the time the prize is awarded, but if you were influential, you get the prize.

You could argue that this is appropriate for what Thomas Kuhn would call a “pre-paradigmatic” science — a field that’s still looking for a set of basic concepts and tools. But it’s been 55 years since they started giving the prize, and that seems like an awfully long time for a field to still be tooling up. Meanwhile, making “influence within the economics profession” the criterion for successful research seems a little too much like a popularity contest. It’s how you end up with prizes like the one in 2004, which was given to some macroeconomic theorists whose theory said that recessions are caused by technological slowdowns and that mass unemployment is a voluntary vacation.

In recent years, that looked like it might be changing. Often, the prize was given to empirical economists associated with the so-called “credibility revolution” — basically, quasi-experiments. Those cases include Goldin in 2023, Card/Angrist/Imbens in 2021, and Banerjee/Duflo/Kremer in 2019. And when it was given to theorists, they tended to be game theorists whose theories are very predictive of real-world outcomes — Milgrom/Wilson in 2020, Hart/Holmstrom in 2016, Tirole in 2014, and Roth/Shapley in 2012. Even when the prize was given to macro — a field where validity is much harder to establish — it was given to economists whose theories have seen immediate application to pressing problems of the day, such as Bernanke/Diamond/Dybvig in 2022 and Nordhaus in 2018.

In other words, the recent Nobels have made it seem like economics might be becoming more like a natural science, where practical applications and external validity are the ultimate arbiter of the value of research, rather than cultural influence within the economics profession. But this year’s prize seems like a step away from that, and back toward the sort of big-think that used to be more popular in the prize’s early years.

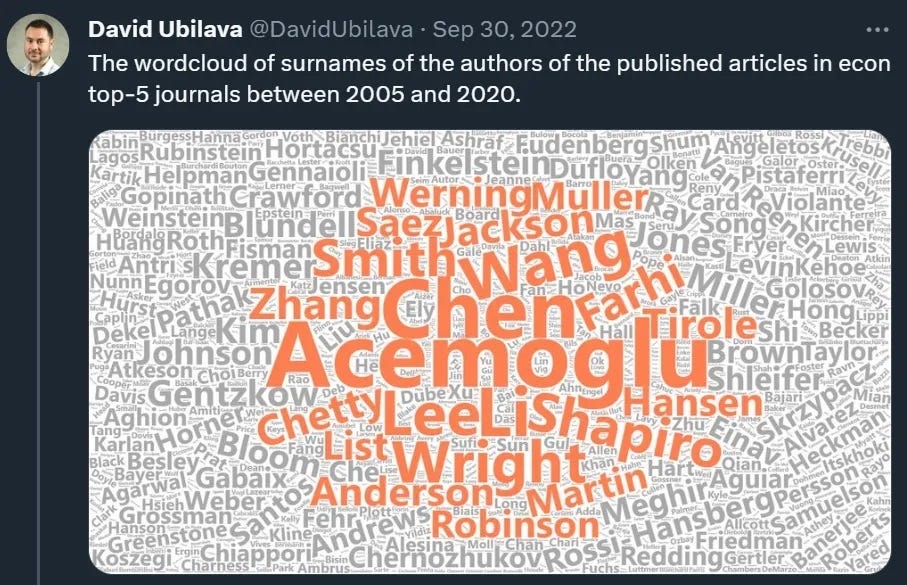

Anyway, a key point about this year’s prize is that Daron Acemoglu was going to win an Econ Nobel at some point. He’s an absolute beast of a researcher — the closest thing economics has to Terence Tao in math. Alex Tabarrok tells the tale:

I think of Daron Acemoglu (GS) as the Wilt Chamberlin of economics, an absolute monster of productivity who racks up the papers and the citations at nearly unprecedented rates. According to Google Scholar he has 247,440 citations and an H-index of 175, which means 175 papers each with more than 175 citations. Pause on that for a moment. Daron got his PhD in 1992 so that’s over 5 papers per year which would be tremendous by itself–but we are talking 5 path-breaking, highly-cited papers per year plus many others!…In his overview of Daron’s work for the John Bates Clark medal Robert Shimer wrote “he can write faster than I can digest his research.” I believe that is true for the profession as a whole. We are all catching-up to Daron Acemoglu.

In fact, this is all you really have to see to get the point:

In physics, as I mentioned, it would easily be possible for a researcher this accomplished to never get a Nobel. In economics it is not possible.2 And when Acemoglu got his Nobel, it was always going to be officially awarded for his single most influential area of research. That would be his research on institutions and economic development.

Which is why Johnson and Robinson, Acemoglu’s key co-authors in that literature, also received this year’s Nobel. That’s not to say Johnson and Robinson are unimpressive researchers on their own! In fact I’m a huge fan of Johnson’s work overall, on finance, place-based policy, technology policy, and other topics near and dear to my heart, as well as his excellent popular writing. But Johnson and Robinson’s most influential research, by far, has been the work they did on institutions with Acemoglu.

What’s an “institution”? No one can quite agree on that point. Conceptually, they could include legal arrangements like property rights, political systems like democracy, bureaucratic organizations, etc. Different researchers tend to mean different things when they say “institutions”, though everyone seems to agree that 1) rule of law, and 2) property rights are important examples.

Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson (whom most people call “AJR”) have a theory that economic development is caused by a country having the right kind of institutions. Specifically, they believe that if institutions are “inclusive” — if they “allow and encourage participation by the great mass of people in economic activities that make best use of their talents and skills and that enable individuals to make the choices they wish” — then a country will prosper. And if institutions are “extractive” — if they ignore human input, waste human potential, and just try to grab resources like free labor or minerals — then a country will stay poor. You may have read this theory in Acemoglu and Robinson’s famous book, Why Nations Fail.

In fact, I love this theory. It resonates strongly on an emotional level, because it agrees strongly with my values. I believe in regular people. I believe that average people have enormous economic and political potential that is usually under-exploited, and I’m constantly annoyed by elitists who think society is driven by a few geniuses. I believe that countries get rich primarily through hard work and ingenuity rather than plunder.

Also, intuitively speaking, I sort of think this theory is right. I look at countries like Russia that devalue their own people and view them as cannon fodder, and I see them doing worse in terms of technology and the economy. I see Xi Jinping cracking down on private entrepreneurship, and I can’t imagine it’ll be good for China’s growth. I look at any number of repressive regimes and see militaries and party-states and mafias that reach their tentacles deep into society, preventing regular people from getting ahead, and producing a feeling of hopelessness. I see how companies that rely heavily on cheap labor often fail to innovate.

Having said all that, though, I don’t think this is the kind of theory you can easily evaluate with evidence. And I don’t find the evidence that Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson have produced to test the institutional theory of development to be extremely persuasive.

For example, take AJR’s most famous paper, “The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation”. In this paper, AJR look at various different former European colonies — rich ones like the U.S. and Australia, and poor ones like Nigeria and Pakistan. They observe that in the rich ex-colonies, people today are at less risk of expropriation by the government. AJR hypothesize that this is because back in the colonial days, European colonialists created strong property rights in the colonies that eventually became rich, and weak property rights in the colonies that eventually became poor.

To test this hypothesis, AJR look at the mortality of European settlers in the various colonies. High settler mortality — generally due to tropical diseases — meant that Europeans couldn’t move to a place like Nigeria en masse, and therefore ruled from afar. Colonialists ruling from afar didn’t really care about property rights, so they just had their armies and their local cronies extract mineral resources and/or slaves, and left the colony as a whole to rot. But if the disease burden was low, the Europeans moved in, and then they needed to put in some property rights. Lo and behold, this hypothesis checks out — the colonies where Europeans didn’t die as much from disease tend to be much richer, and to have better property rights, in the modern day.

This methodology is clever, and the result agrees with our intuition. But a couple of years after it came out, some other economists started pointing out some big flaws. In particular, Glaeser et al. (2004) pointed out that in places where Europeans were able to settle, they didn’t just bring property rights and other institutions — they brought themselves. Glaeser et al. note that it’s impossible to empirically disentangle the growth effect of the institutions from the growth effects of human capital — i.e., the effect of just having a bunch of European-descended people in your country.

Now, that may sound like a racial theory, but it’s not.3 For one thing, culture might be just as long-lasting as institutions themselves. But I think there’s an even more important reason why having European-descended people in your country would cause economic growth — they traded a lot with Europe. Americans and Australians and Canadians got lots of ideas from the UK and Germany and France — technologies, business models, etc.4 And they established incredibly lucrative trading networks with European countries, often from a place of equality rather than as a subordinate province of empire.

This alternative explanation for AJR’s famous result has never been rejected, and it’s so important that the Nobel committee saw the need to issue a disclaimer about it in their prize announcement:

[A]scribing causality to such an…estimate requires strong assumptions. In short, it requires an “exclusion restriction,” i.e., that the only reason why the mortality rates among European settlers centuries ago affect GDP per capita today is because of their effect on contemporary institutional quality…A more serious concern for the validity of the exclusion restriction is if the settlers also brought with them their know-how and human capital, and if these factors have had a direct effect on long-term prosperity for a given set of colonial institutions…Ultimately…human capital and institutions are both determinants of growth, and it is very hard to distinguish Acemoglu, Gallego, and Robinson’s argument from the fact that human capital has an independent effect on growth…The [AJR] estimate should thus be taken with a grain of salt. Nevertheless, the evidence presented by Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson strongly suggests that the type of institutions implemented by the colonizers is a key mechanism driving the relationship between contemporary GDP and the conditions at colonization.

This is a pretty startling thing to have to put in a Nobel Prize announcement, isn’t it? It basically amounts to saying “Well, this result doesn’t actually prove the researchers’ hypothesis, and in fact the hypothesis probably can’t be proven, but we’re going to give it a Nobel anyway because it’s strongly suggestive.” If you want economics to be more of a science and less of a branch of philosophy, that’s not the kind of thing you want to have to write!

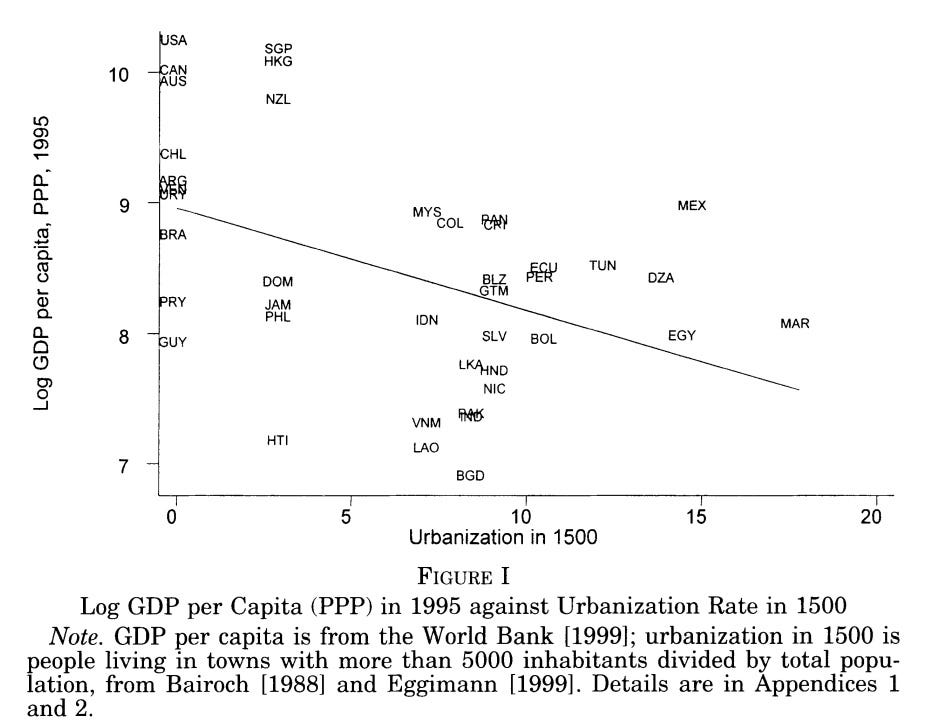

The Nobel committee defends this move by referencing a second famous AJR paper, from 2002: “Reversal of Fortune: Geography and Institutions in the Making of the Modern World Income Distribution”. In that paper, AJR show that European colonies that were rich before colonization became poor afterwards, while colonies that were poor before colonization became rich afterwards. And as a measure of wealth and poverty, they use urbanization. So they come up with this chart:

AJR’s argument here is that because the rich and poor places flipped places between 1500 and 1995 — as demonstrated by that downward-sloping line — it must mean that geography can’t explain wealth and poverty. Instead it must be institutions.

But this has the same problem as the other famous paper. The places like the U.S., Canada, and Australia — the “poor” colonies that later became rich — are the places that filled up with Europeans and their descendants. The places that were more urbanized in 1500 and were poorer later — like Egypt, Mexico, and Vietnam — are places that didn’t get a ton of Europeans moving in, possibly because they already had a lot of people there (or had more tropical diseases, or whatever).

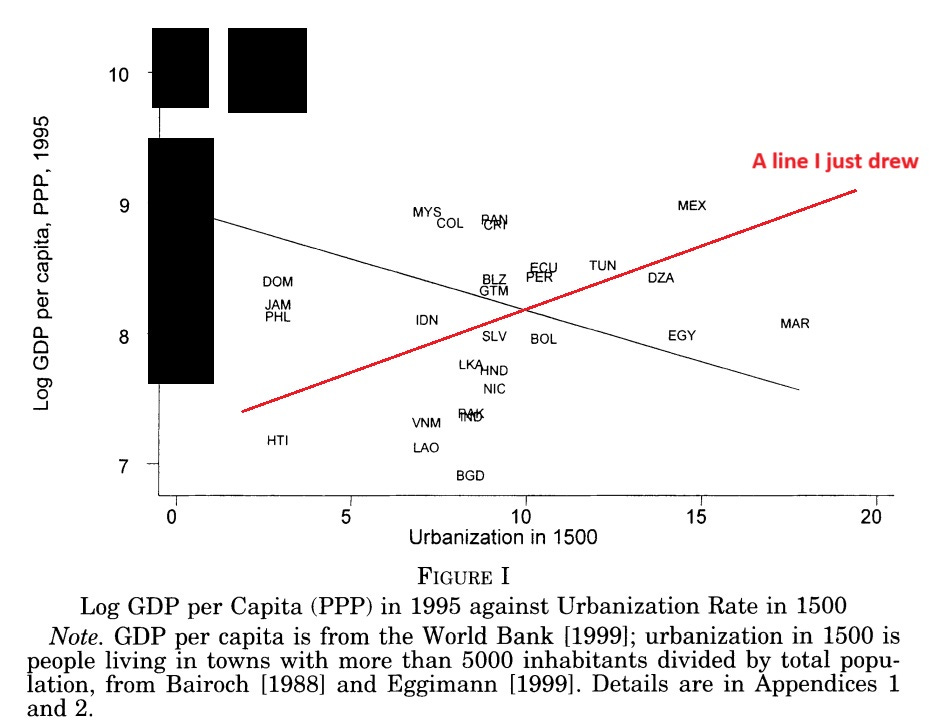

Let’s try something, just for fun. Let’s black out a few rich places that were pretty empty, and which the Europeans filled up with colonists (including Singapore and Hong Kong, which they filled up with Chinese folks they recruited), and then see what the trendline looks like:

It looks like the “reversal of fortunes” has…reversed.

OK fine, that wasn’t a particularly scientific exercise on my part. But Chanda, Cook, and Putterman (2014) did this exercise rigorously, and found that, lo and behold, once you account for population relocations, AJR’s “reversal of fortune” gets reversed:

Using data on place of origin of today's country populations and the indicators of level of development in 1500 used by Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson (2002), we confirm a reversal of fortune for colonized countries as territories, but find persistence of fortune for people and their descendants. Persistence results are at least as strong for three alternative measures of early development, for which reversal for territories, however, fails to hold. Additional exercises lend support to Glaeser et al.'s (2004) view that human capital is a more fundamental channel of influence of precolonial conditions on modern development than is quality of institutions.

Once again, “Europeans implementing good institutions” is just impossible to distinguish empirically from “Europeans moving in.”

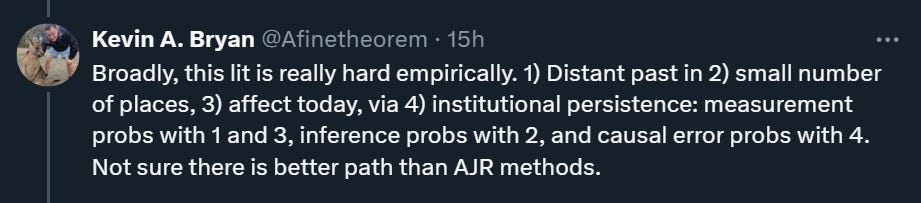

Note that I am not accusing Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson of doing shoddy empirical work.5 It’s just inherently very very hard to look at the history of countries 500 years ago and draw strong empirical conclusions about the deep fundamental causes of economic development. That is, inherently, an incredibly difficult exercise. Kevin Bryan has a good thread explaining, briefly, some of the reasons why it’s so hard:

Anyway, those are only the two most famous papers in a long series of papers in which AJR (or sometimes just AR, or sometimes just Acemoglu) attempt to theorize how institutions affect growth — basically, political science theories about the relationship between elites and the masses. That’s very interesting stuff. But without solid empirical confirmation that institutions really do affect growth in the way that AJR hypothesize — confirmation that may simply be impossible to get — there’s always the chance that those theories are “explaining” a phenomenon that doesn’t actually exist.

The same issue crops up regarding Acemoglu and Robinson’s recent work with Suresh Naidu and Pascual Restrepo on the impact of democracy on growth. The paper is entitled “Democracy Does Cause Growth”, but as Alex Tabarrok notes, the effect they find is actually pretty small:

In other words, if the average nondemocracy in their sample had transitioned to a democracy its GDP per capita would have increased from $2074 to $2489 in 25 years (i.e. this is the causal effect of democracy, ignoring other factors changing over time). Twenty percent is better than nothing and better than dictatorship but it’s weak tea.

A small effect like this is usually susceptible to being reversed by the inclusion of an omitted variable that was initially left out. For example, Park (2024) argues that democratic countries putting economic sanctions on nondemocracies in recent years can explain all of the small economic benefits of being a democracy:

This paper argues that the observed positive effects of democracy are largely due to a "democratic favor channel," where powerful democratic nations, their allies, and international organizations treat democracies more favorably than nondemocracies…[W]hen controlling for sanctions imposed by the US, its G7 allies, and the UN, the positive effects of democracy weaken or turn negative…I show that these democratic favors serve as plausible channels through which democracy appears to drive economic growth.

If Park is right, then the economic benefits of democracy are simply an accident of the last few decades of history, in which the U.S. and its allies happened to be very powerful and used their power to put their thumb on the economic scales a bit.

Is Park right? I don’t know. But the point is that the entire literature is filled with things like this. Cross-country regressions are inherently limited tools for explaining the wealth and poverty of nations. The kind of questions AJR purport to answer may never really be answerable, or at least not for the foreseeable future.

Anyway, I definitely don’t mean to criticize Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson for doing this research. It’s good to think about the big questions of history, development, institutions, and national wealth. Though those questions aren’t often answerable with the kind of credible empirics that economists use for more small-bore microeconomic questions, but they’re still very important. We may never get definitive answers, but thinking about these things is better than not thinking about them. And as I said before, I really like the answers AJR came up with, and I think there’s a decent chance they’re actually true.

But I also don’t think every interesting line of research needs a Nobel Prize. I was happy to see the Econ Nobel move toward rewarding research that was more scientific and less philosophical than in the past. It was part of econ’s general trend toward being a more humble, grounded, reliable, applicable science. This year’s award moves in the opposite direction, back toward philosophical big-think.

And none of them have anything to do with whether it’s a “real Nobel”. Whether a 19th-century arms manufacturer said in his will that your academic subject ought to have a prize named after him is a poor guide to how prestigious that prize should be.

OK, well, it’s possible, but there have to be extenuating circumstances. Andrei Shleifer is even more well-cited than Acemoglu, but he had a corruption scandal involving Russia in the 1990s, which will probably prevent him from ever getting the Nobel.

Well, I’m sure someone out there thinks about this in racial terms, but it certainly doesn’t have to be.

Of course, they also probably brought institutional knowledge with them. This is one more reason why the institutions hypothesis and the human capital hypothesis can never be disentangled.

Note that some people do have complaints along those lines. I am not going to try to adjudicate those complaints here.

I got to meet Daron Acemoglu when I was a PhD student.

I did my PhD in Game Theory. My advisor was buddies with Daron and also his wife, who was an EECS professor, also at MIT. There were a few multi-university grants that one or both of them, and we, were a part of. There were periodic meetings that Daron would attend with us, although I never worked with him directly.

Daron, unlike many other economists, was open to working with people in other, less "glamorous" fields. Possibly, he felt more comfortable than others in doing that because he was already so famous. Around fifteen years ago when I first met him, it was already common knowledge in econ circles that his Nobel was inevitable. He just needed to wait for his turn.

It was definitely not lost on any of us researchers that Daron's work was somewhat arm-chair and grandiose. Not bad or wrong, but quite different to what was expected from the average researcher. It was pretty clear that a lowly PhD student could not get the same acclaim for the same type of work. I remember asking about this and being told by some faculty that Daron himself acknowledged privately the tremendous role of what he called "charm and persuasion" in his own personal success. This was simply how econ worked, it was explained to me.

I didn't take any of this to imply Daron was some kind of charlatan. Rather, just that the culture that elevates Daron predates and is bigger than Daron himself. Don't hate the player, hate the game, if you will.

I think they should be criticized.

Pretending that this kind of essayism is scientific because you include a few models / graphs / formulas is eroding trust in actual science. I agree that this kind of enquiry can be important for the general discourse (and I definitely find it entertaining) – so they should write essays and label them correctly.