Why Japan opened itself up to immigration

And why your country probably will, too.

Noah’s First Law of Japan Discourse is that if a debate in the U.S. goes on long enough, someone will eventually cite Japan as support for their position.

Noah’s Second Law of Japan Discourse is that 80% of such arguments will be wrong.

Both of these laws were firmly on display in the recent battle over high-skilled immigration. The Tech Right pointed out (correctly) that skilled immigration is essential for America to retain its competitive edge in high-tech industries. Some on the Nativist Right tried to argue with that America would do just as well if it banned immigration from India and put more resources toward training its own STEM workers. When it became apparent that this was a ridiculous assertion (U.S. tech workers are already well-trained, but the U.S. has only 4.4% of world population, so our domestic talent pool is limited), some on the Nativist Right switched to a new argument: Economic prosperity is unimportant compared to racial homogeneity.

Predictably, Japan was trotted out as an example of why this is a good idea:

As a professional Guy Who Knows Slightly More About Japan Than the Average Westerner Does, I feel it is incumbent upon me to debunk this latest piece of mythmaking. As with most such misconceptions, the idea that Japan kept itself racially pure, and remained economically successful despite this choice, contains a few small grains of truth wrapped in many thick layers of lazy stereotyping, wishful thinking, and out-of-date information.

The small grains of truth here are:

Japan remained unfavorable toward immigration for longer than most rich countries.

Japan remained a nice place to live in the 1990s and 2000s despite not taking in many immigrants.

But the key facts that bust the Nativist Right’s myth of Japan are:

Japan has opened itself up to large-scale immigration since the early 2010s.

Japan has suffered a severe and prolonged stagnation in wages and living standards, and this was the main reason it opened up to immigration

The key to understanding Japan is that in most respects, it’s actually a pretty normal developed country, despite the different visual style and cultural quirks. Its evolution on immigration hasn’t resembled the U.S., Canada, or Australia, but it has been roughly similar to that of many European countries.

And that means the story of Japanese immigration is a complex one. The aggregate economic impacts are still unclear. The country was divided on the question of whether to take in immigrants, and with good reason — a large enough flood of foreigners, especially from places more culturally distinct from Japan, will definitely put strains on the country’s famously orderly society. Those strains won’t be exactly the same as in Europe, but some of the broad contours will be similar.

In fact, I would say that I’m personally more apprehensive about those changes than the average Japanese person. Still, I think it’s important that we not tell ourselves myths about Japanese policy, the Japanese economy, or Japan’s racial homogeneity. Comparing ourselves to a fantasy Japan will actively hurt our ability to shape a real future for America.

The story of how Japan opened up to immigration

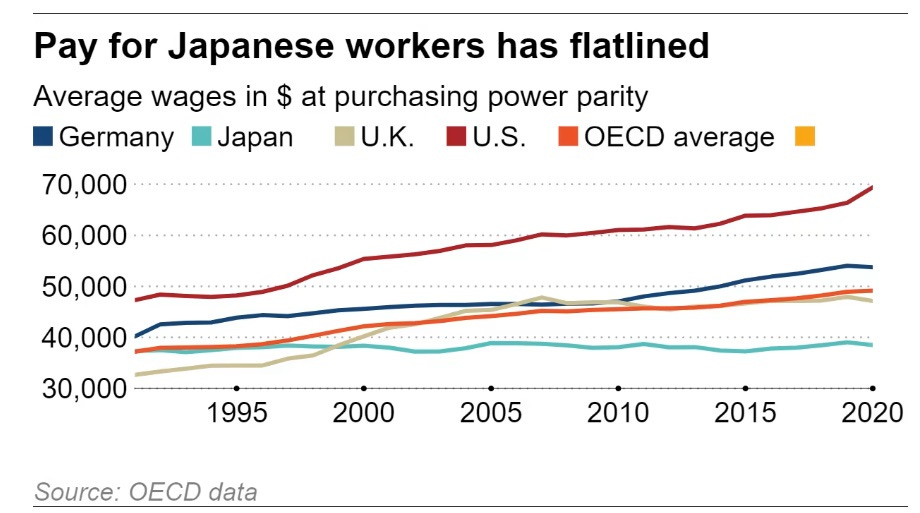

The first thing to understand here is that Japan did not “protect [its] wages”. Starting around the mid to late 1990s — around the time of the Asian Financial Crisis — Japan’s real wages began to gently decline, even as wages in most developed countries continued to rise. This is from an article by Matsuo Yohei in Nikkei Asia in 2021:

Annual real wages in Japan averaged about $39,000 in 2020 at purchasing power parity last year, an increase of just 4% from 30 years earlier, according to data by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Over the same period, U.S. wages jumped by roughly half to $69,000, and the OECD average rose by a third to $49,000…

…Yet while income gaps are not as wide in Japan as elsewhere, the wage data shows an overall lowering of living standards, for rich and poor…

Companies are under pressure to boost employee compensation, but doing so is difficult for many without domestic growth to fund it…Sales more than doubled at overseas units of Japanese companies over the past two decades, but domestic sales climbed only 7%…Sustained wage growth will require companies to add value to their Japanese operations[.]

Along with three decades of wage stagnation came a stagnation in living standards for regular Japanese people. I wrote about this in a recent post:

As I explained in that post, this manifested as a lack of increase in purchasing power, but also as an increase in toil. Eldercare duties increased as the population aged. And the country put a whole lot more of its people to work.

For example, women. Starting gradually in the 2000s, but then at a very rapid pace after Abe Shinzo took over the country in late 2012, jobs became the universal norm for Japanese women in a way they had not been before:

This is great from a standpoint of gender equality, but it also just means a lot more work for women, since gender roles mean they still get stuck with the bulk of child care, housework, and the increasingly brutal burden of eldercare.

Many of the elderly went to work as well — a trend that began in the early 2010s and continues to this day. Teenagers and young adults too — from 2003 to 2023, the rate of unemployed people age 15-24 declined from 10% to 4%.

I’ve been going to Japan since the early 2000s, and I could really feel this change — two decades ago it felt like there were a lot of Japanese people who had the leisure time to pursue personal fulfillment, art and self-expression, travel, and so on. Now, everyone works, all the time. But despite this increased toil, in material terms, their lives are much the same — they live in much the same smallish, poorly furnished houses and pinch pennies at the grocery store.

This makes me sad, but by and large, this was not the reason Japan opened up to immigration — or at least, not how policymakers thought about the issue. They weren’t thinking about living standards, or home furnishings, or vacations, or art, or GDP, or making “line go up” — instead, they were thinking about labor shortages.

From the 90s through the early 2010s, Japan aged at a stupendous pace. In 1991 there were more than 4 Japanese working-age adults for every Japanese person over 64. By 2023 there were fewer than 2:

This wasn’t just because the number of old people increased; Japan’s total working-age population peaked and began to decline in the late 1990s:

As Japan aged, Japanese companies had a certain amount of demand for their products, and fewer and fewer prime-age men to create those products. If you go back and read news stories about the Japanese economy in the 1990s and early 2000s, you’ll see that “labor shortages” get mentioned a lot. These shortages weren’t just in farming and manufacturing — it was getting hard to find checkout clerks, nurses, taxi drivers, eldercare workers, and so on.

Whether these “labor shortages” are true shortages in the economic sense of the term is an interesting and subtle question,1 but it doesn’t matter much for our purposes here. The deeper point is that due to a reduction in the working-age Japanese population, Japanese companies had to choose between several options:

Shrink their operations and sell fewer products

Accept lower profit margins

Produce more overseas (offshore)

The second and third of Japanese companies did do a lot of offshoring in response to population decline; this led to increased profits but also contributed to rising inequality, since corporate owners reaped the benefits but most Japanese people did not.

This left companies in a bind. They wanted to produce more in Japan, but doing this was difficult. Simply raising wages wouldn’t attract more prime-age Japanese men into the labor force, because they were basically all already in the labor force. Companies could change their cultures to accept more women and old people as full-time workers, but they were reluctant to do this.

Instead, in the 90s, Japanese companies had the idea to take in immigrants. Cultural fit was definitely a worry — the older Japanese generation was very concerned that foreigners wouldn’t integrate well into Japan’s orderly, rule-based culture. And the older generation definitely thought of culture at least partially in terms of race.

So in the 90s, Japanese companies — together with the government, which works closely with large Japanese businesses — had the idea to recruit ethnic Japanese people from Brazil and Peru, where many had emigrated in the postwar period. These imported Brazilian and Peruvian guest workers became known as the “dekasegi”, and they filled mostly menial jobs — farm and factory labor.

It didn’t work. The dekasegi looked Japanese, but culturally they didn’t really fit in. By the late 2000s, the Japanese government was paying them to leave the country en masse:

Japan’s offer [of payments to leave the country], extended to hundreds of thousands of blue-collar Latin American immigrants, is part of a new drive to encourage them to leave…So far, at least 100 workers and their families have agreed to leave, Japanese officials said…The program is limited to the country’s Latin American guest workers, whose Japanese parents and grandparents emigrated to Brazil and neighboring countries a century ago…Under the emergency program, introduced this month, the country’s Brazilian and other Latin American guest workers are offered $3,000 toward air fare, plus $2,000 for each dependent…But those who travel home on Japan’s dime will not be allowed to reapply for a work visa. Stripped of that status, most would find it all but impossible to return.

Officially, the reason for this was economic — worries that the dekasegi guest workers would compete with native-born Japanese people for jobs. And indeed, that was part of the reason, since this program to pay the dekasegi to leave was implemented during the recession of 2008-9. But unofficially, some of the reasons were cultural, and crime was a part of it.2 I can’t prove that to you with data, but you’ll note that the offer to pay people to leave applied only to the Latin American guest workers.

Japan thus discovered that race and culture are two very different things.

The labor shortage hadn’t been solved. When the country emerged from recession — and from the aftermath of the 2011 earthquake — it went to Plan B. Under pressure from the Abe government, Japanese companies started hiring women, the elderly, and the semi-idle young. This required a lot of cultural changes at hidebound, conservative Japanese companies, just as expected. Those changes are proceeding, slowly and sometimes painfully.

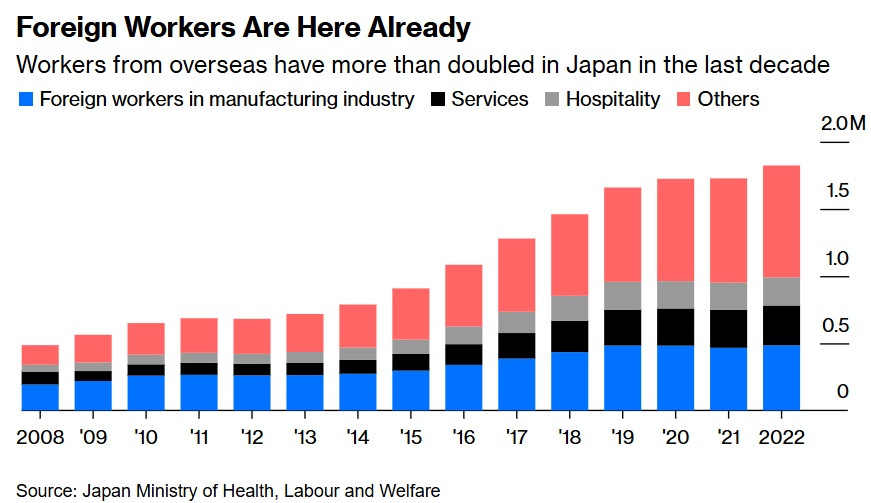

But Abe also did a second big thing to fill Japanese companies’ labor needs — he opened up the country to immigration. The number of foreign workers in Japan rose by a million over Abe’s tenure in office, paused during the pandemic, and then began to rise again:

People who desperately want to think of Japan as a racially homogeneous closed society will look at these numbers and squawk that the percentage of foreigners in Japanese society is still low compared to most Western countries. This willfully ignores several things. First, the numbers in the chart above represent only foreign workers, not students, children, non-working spouses, or the elderly or disabled, who together constitute over a third of the true foreign population. Second, it doesn’t include naturalized Japanese citizens or children of mixed marriages. Third, and most importantly, it ignores the rapid rate of increase.

Gearoid Reidy sets the record straight:

Take a closer look at that data from last week, however. It shows the number of foreigners rose 11% from a year earlier to comprise 2.4% of the total population, or just under 3 million people; as the figures are from Jan. 1, that milestone has now likely already been passed. It often goes unremarked that the number of workers from overseas has more than doubled in the last decade alone, while the broader foreign community (including students and families) has risen 50%…Based on population projections, conversation has already been shifting to a future where foreigners will make up more than 10% of people in the country 50 years from now — similar to the current levels of the US, UK or France…

Already, this change is tangible — one only needs to go into any of the ubiquitous convenience stores in Tokyo or other major cities. Not long ago, it was a novelty to see a foreigner behind the counter; these days, it feels more unusual to see a Japanese…

Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has expanded a visa that allows foreign laborers and their families to stay in Japan indefinitely from just two industries (construction and shipbuilding) to 11, including the extremely stretched service sector. “We have to consider a society where we coexist with foreigners,” Kishida said at a speech last month…For white-collar professionals, initiatives include a fast track to permanent residency for high-earners. The government is also studying the introduction of a “digital nomad” visa to attract those who can live and work anywhere. Another goal is to attract 400,000 foreign students by 2033, from a little over 300,000 before the pandemic, with half staying on for employment[.]

(This article was from 2023, when Kishida was still prime minister.)

And here’s what I wrote back in 2019 when Abe was still in charge:

In 2018, 1 out of 8 young people turning 20 in Tokyo wasn't born in Japan. That doesn’t even count the people who were born in Japan but aren’t ethnically Japanese. Although Tokyo isn’t close to becoming a multiracial metropolis like New York City or London, the word “homogeneous” no longer fits the city…

In recent years, the Abe administration has adopted major changes that will probably sustain the influx of immigrants. In 2017 Japan implemented fast-track permanent residency for skilled workers. In 2018 it passed a law that will greatly expand the number of blue-collar work visas, and -- crucially -- provide these workers with a path to permanent residency if they want it.

These changes thus represent true immigration, as opposed to temporary guest-worker policies (despite the common use of the term “guest worker law” to describe the new visas). In time, it will mean a more ethnically diverse Japanese citizenry. Permanent residents are allowed to apply for Japanese citizenship after five years. Some foreigners will also marry Japanese nationals, and their children will thus be citizens as well. Since the new law prevents visa holders from bringing families with them to Japan, many of the new workers will likely be single people looking for spouses, making them more likely to marry locals.

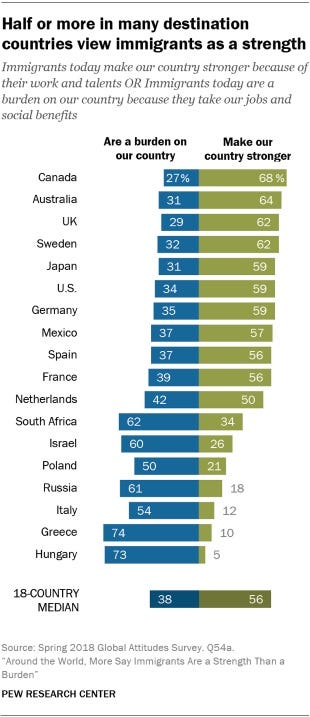

The thing that will most gall the people who want to imagine Japan as a closed, homogeneous paradise is that by and large, Japanese people want this. In poll after poll, Japanese people report some of the world’s most positive attitudes toward immigrants — often more positive than America itself. Here’s one from 2019:

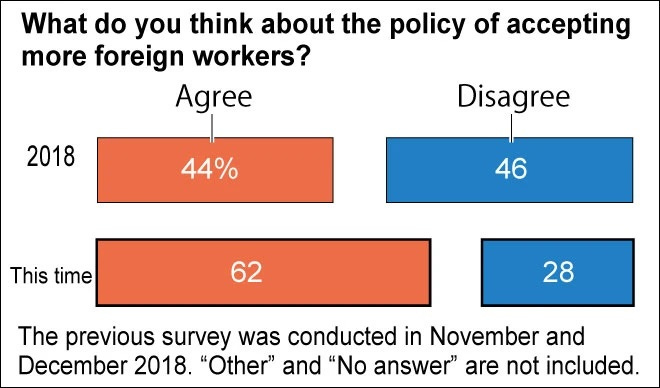

And here’s a 2024 poll showing Japanese people becoming increasingly supportive of policies to attract more foreign workers:

The Asahi reports:

Increases in approval [for accepting more foreign workers] were seen among all age groups, but the rises were particularly sharp among older respondents…In the 2018 survey, only 35 percent of people in their 60s were in favor of bringing in more foreign workers. The ratio jumped to 63 percent in the latest survey…Among those 70 or older, the support ratio climbed from 38 percent to 62 percent…Generational differences concerning the policy have nearly disappeared…In the 2018 survey, 60 percent of respondents between 18 and 29 approved of the policy. The ratio is now 66 percent.

The government has revised its foreign worker system to allow more people into the country to address labor shortages in various industries. It also allows the workers to stay in Japan longer, along with their families, on permanent resident visas…

Fifty-seven percent of respondents supported the idea of “expanding permanent residency for foreign workers and their families,” while 33 percent opposed the idea.

Does this mean that Japan is a liberal, open, tolerant paradise? No! A sizeable minority still opposes increases in immigration. And the country has all of the usual disagreements and anxieties about racial identity and demographic change. Japanese social media erupted with right-wing rage when a half-Black, half-Japanese woman won a beauty pageant. Liberals leapt to the beauty queen’s defense, and it became a culture-war battle similar to what America experiences every time Hollywood replaces a White character with a Black one.

When a half-Indian woman won a pageant a year later, there was far less of an outcry. But an undercurrent of anger and fear over Japan’s changing demographics remains, as it does in Europe, the U.S., and everywhere else. That doesn’t mean Japan itself is a xenophobic country; it means that it has a xenophobic minority, and a “normie” populace whose opinion on immigration and diversity are capable of shifting based on events.

In fact, I expect the pendulum in Japan to swing back to a more skeptical position on immigration at some point. A friend of mine — who grew up in America, and has always called for Japan to admit more foreigners — recently groused about a neighborhood where a mosque’s daily call to prayer disturbs the peace and quiet of local residents. And there was an incident in 2023 where a Muslim immigrant from Gambia vandalized a Shinto shrine in Kobe, while harassing Japanese worshippers and declaring that “There is no God but Allah.”

More incidents like this will happen. In unruly America this would be a very minor incident, but in sleepy, orderly Japan they will make the news. Japanese intellectuals will try to downplay the incidents as statistical aberrations, or even portray them as a response to discrimination by the ethnically Japanese majority (as they did in the case of the dekasegi). Regular people will probably become more immigration-skeptical — whether by a little or a lot will depend on the frequency and severity of such incidents.

Most damaging will be if there is a series of high-profile violent crimes by immigrants — rapes, aggravated assaults, and/or murders. Japan is a famously safe society, where kids and women can walk around without fear at night, even in downtown areas. A few sensational immigrant street crimes could raise fears that this safety is under threat, and prompt calls for curbs on immigration.

I think there is a decent chance that this will happen, and I fear the consequences when it does. Japanese people deciding that their country isn’t safe anymore, even if that decision is based on the availability heuristic and media sensationalism, would be a terrible cultural loss. And the resulting backlash against immigration would do the country no favors either. We’re seeing these processes play out in a number of orderly, formerly homogeneous North European countries, and it is not a pretty one.

I am thus personally more skeptical of immigration to Japan than the average Japanese person is! Japan is not America — it’s not a country that traditionally defines itself as a nation of immigrants, and it’s not a country that’s used to dealing with unruly people and violent crime.

That’s why I think Japan’s government needs to be more proactive and farsighted about how it deals with immigration — simply copy-pasting America’s libertarian approach will not be optimal. It needs to focus more on high-skilled immigrants, since people with good jobs are less likely to turn to crime. It needs to implement active assimilation policies, like making sure that everyone learns to speak Japanese.3 And it should try to bias its immigration system toward countries that are already culturally not too distinct from Japan, such as Vietnam.

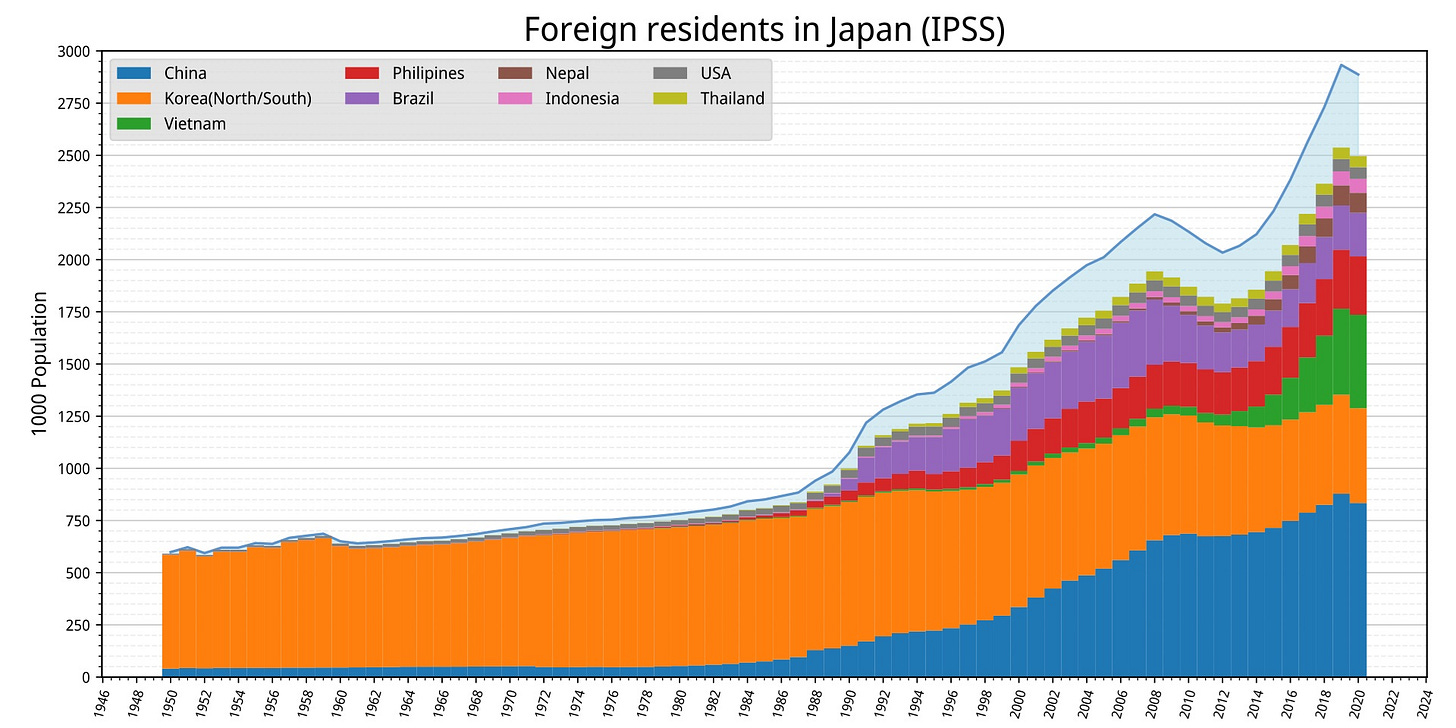

In fact, Japan is already doing the latter. Most of Japan’s recent immigration has come from Vietnam and the Philippines, with a little bit from China:

There have been a few minor tensions with Vietnamese immigrants — one Japanese person I know complained of them catching and eating doves — but overall there have been very few issues. The reason is not racial similarity, as we saw with the Brazilians — in fact, Japanese people can spot ethnic differences fairly easily, and don’t actually consider Vietnamese people to be the same race as them. Instead, it’s about cultural compatibility. This is something Japan simply needs to worry about a lot more than America does.

But all that aside, I think what Japan’s experience shows is that every rich country is going through broadly similar things when it comes to immigration. The fundamental driver of the issue is population aging. This is happening all over the world, even in poor countries — fertility decline is accelerating all over the world, with no bottom in sight. By some reports, the human race is already at replacement-level fertility. And so far, no one has found a way to stop this:

One thing that definitely won’t work is for conservatives to yell in the media for people to have more kids. Japan has already tried this of course — the country’s health minister called on women to have more children back in 2007, calling them “birth-giving machines”,4 and provoked a furious backlash. Rightists who shout on X for American women to have more kids will encounter no more success than he did.

Population aging leads to perceived labor shortages — all kinds of businesses and other organizations have to choose between hiring foreigners and shrinking their operations. “Just raise wages” is not a solution to these labor shortages, because after you put all of your domestic population to work — as Japan did in the 2010s — there’s simply no pool of unused domestic labor for higher wages to attract. Once you put all the locals to work, the only solution to perceived labor shortages is immigration.

And in general, people in rich countries will choose immigration over decline as a response to perceived labor shortages. Instead of simply accepting a society with fewer convenience stores, fewer nurses, and so on, they will choose a society that looks mostly like the one they grew up in. If the face of the convenience store workers and the nurses becomes a foreign face, that’s definitely a change, but it’s less of a change than living in a withering, shrinking, dying country.

So again and again, rich countries — no matter how homogeneous, no matter how orderly, no matter what their attitudes on race and culture — choose immigration over shortage and decline. Japan did it. Korea is doing it. China is too big for it to make much of a difference, but it will try anyway. And with immigration will come all the usual problems, challenges, arguments, political divisions, and uncomfortable tradeoffs. Different countries and cultures will manage these in different ways, and not all of them will manage them well.

But this is the future. This is what the 21st century is going to be like, for everyone. Unless and until someone figures out how to reverse humanity’s fertility decline, this is going to be the story everywhere.

The argument that they were a true shortage is that cultural norms against hiring women and the elderly, along with government restrictions on immigration, prevented the market from clearing at the prevailing wage. Whether you accept the first argument depends on whether you view discrimination as a form of nonmonetary compensation for company owners, or as an externally imposed policy. The second is pretty obviously correct, but only libertarians like to talk about it this way.

And yes, Japanese intellectuals and elites often framed this in terms of “discrimination” against the Latin American guest workers by the Japanese majority. Wokeness is not as uniquely American as we like to think.

Ironically, the article I wrote for Bloomberg about Japan’s need for active assimilation policies gets passed around Rightist Twitter as an example of me calling for more immigration to Japan, probably because Bloomberg gave the post a very pro-immigration headline. Rightist Twitter isn’t particularly smart.

This was probably meant as a nerdy metaphor rather than a misogynistic insult, but it was definitely perceived as a misogynistic insult by Japanese women.

Happy New Year Noah!

Interesting article, but this part is off the mark (sorry, Noah):

“Its evolution on immigration hasn’t resembled the U.S., Canada, or Australia, but it has been roughly similar to that of many European countries.”

Pretty much every Western European country has been taking in way more immigrants way before Japan, and most Central and Eastern European countries have started to do so at a far earlier stage of economic development than Japan as well.

You're very knowledgeable about Japan and that's great! But some of your casual remarks about Europe are just off the mark.

Yes, Australia and Canada are special. Net migration rates to the US, however, are actually closer to those of many European countries than the rates of those are to Japan (and it's been like that for a while).