Indian immigration is great for America

This isn't ambiguous.

The new MAGA coalition has officially had its first internal debate, and it’s over H-1b visas. It started when Trump appointed Sriram Krishnan, a former Twitter exec and Andreessen Horowitz partner, to be a senior AI policy advisor. Krishnan has been a vocal supporter of skilled immigration. This angered some right-wing activists, including an anti-immigration group calling itself “US Tech Workers”, as well as Laura Loomer, Charles Haywood, and other MAGA shouters:

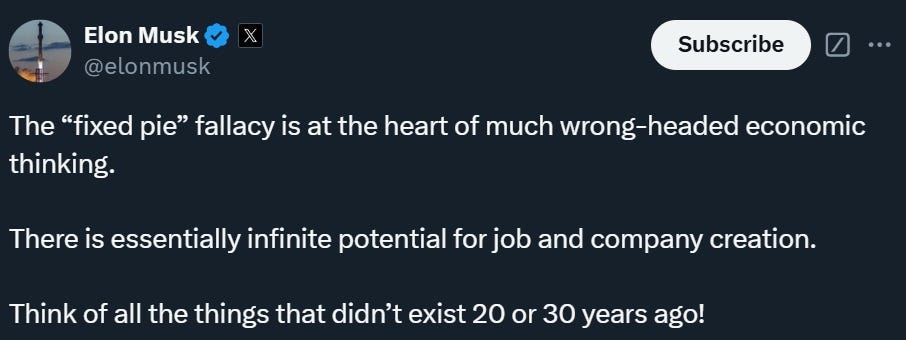

Various figures on the Tech Right, including Elon Musk, David Sacks, and Joe Lonsdale, gamely stood up for Krishnan and for the idea of high-skilled immigration in general:

A tremendous fracas ensued on X, which has basically become the in-house conversation room for the American right. Far-right trolls (including the pathetic but persistent “groypers”) jumped in to attack Indians as a group, and Indians jumped in to defend themselves. Meanwhile, more intellectual discussion shifted to the H-1b visa, which — though not the same as the green card issue that Sriram was talking about — has become a focal point of right-wing pushback against high-skilled immigration.

The debates over high-skilled immigration, Indian immigration specifically, and programs like H-1b are closely related — increasingly so, in fact. Most H-1b workers are Indian, and Indians make up a plurality of foreign-born STEM workers. Indian workers have become far more important than Chinese workers to America’s strategic high-tech industries:

And although Indians are now the second-biggest group of foreign-born residents in America (behind Mexicans, of course), they are also the most successful by many measures — their median household income far exceeds that of any other group.1

And Indian Americans are now influential well beyond STEM and the tech world — for example, in politics. Kash Patel has been nominated to head the FBI, and Vivek Ramaswamy is helping to lead the new Department of Government Efficiency. Even Vice President JD Vance’s wife is Indian! Although Indian Americans still lean a bit toward the Democrats on average, they’re becoming more evenly split between the parties — there are a substantial number of Indians on the right now, despite the presence of another faction of the right that doesn’t particularly like Indians.

So the debate over skilled immigration is actually just part of a broader debate about the fast-growing role of Indian and Indian-American people in the U.S. elite. But first, let’s talk about skilled immigration on its own merits.

H-1b workers are good for American tech workers (and for American workers in general)

First, let’s point out that skilled immigration overall is very important and good for America. Elon Musk is right when he says “If you force the world’s best talent to play for the other side, America will lose.” Here two Noahpinion posts that lay out the case pretty exhaustively:

In fact, the American people pretty strongly agree. A recent Pew poll found that an overwhelming majority of Americans place a priority on letting in highly skilled workers:

Other polls find the same thing.

But H-1b is a little different. Technically, the H-1b is a “nonimmigrant” visa — you can only work in the U.S. for six years before returning to your home country. In practice, many H-1b workers apply for employment-based green cards while they’re here, which is one reason why people casually refer to H-1b as “immigration”, but it’s really a guest worker program.

The question is whether those guest workers hurt American workers in the tech sector.

The lobby group “US Tech Workers” would certainly have you believe so. That group does not represent any organization of actual U.S. tech workers — it’s an arm of the Institute for Sound Public Policy, a political pressure group set up by Kevin Lynn. Lynn’s experience in the tech industry amounts to about 2.5 years doing business development for a couple of startups in the early 2000s; he doesn’t appear to have ever done the type of job that an H-1b worker might be hired to do. His cofounders have even less experience in the tech industry. So this is just a nativist group that claims to represent a class of workers that it doesn’t actually represent, on the theoretical grounds that the presence of foreign workers hurts American workers.

But does that theory hold any water? The basic idea is that an influx of foreign labor is a positive shock to the supply of tech workers. When supply goes up, price goes down — that’s Econ 101.

Now, I often remind readers that immigration as a whole doesn’t seem to decrease native-born American wages. And that’s true — immigrants don’t just work, they also buy stuff, and that increase in demand roughly balances out the increase in supply. But in a specific sector, immigration definitely could decrease wages for the native-born. If you let in a ton of STEM workers, they could drive the price of STEM labor down, while their demand for local goods and services drives up wages in other industries. In this case, American labor as a whole wouldn’t be affected, but American STEM workers would get the short end of the stick.

Interestingly, thought, this doesn’t seem to happen in practice! The H-1b program involves a lottery system, so by comparing companies whose applicants win the lottery with those whose applicants lose, we get a very good randomized natural experiment that can teach us how the H-1b program changes the fortunes of companies. On top of that, there have been occasional changes in the total number of H-1b visas, so we can also look at the results of those policy changes on companies that are more dependent or less dependent on H-1b workers.

Any way you slice it, it doesn’t look like H-1b workers hurt the native-born, even when they seem to be in direct competition:

Mayda et al. (2017) found that when national H-1b numbers were restricted, employment for similar native-born workers didn’t rise.

Mahajan et al. (2024) found that companies who won the H-1b lottery didn’t hire fewer “H-1b-like” native-born workers. They conclude that “lottery wins enable firms to scale up without generating large amounts of substitution away from native workers”.

Kerr et al. (2015) find that when companies successfully hire more H-1b workers, they employ more skilled native-born workers than before.

Peri, Shih, and Sparber (2015) look at the city level instead of the company level, and found that “increases in STEM workers are associated with significant wage gains for college-educated natives.” This should help quiet fears that companies that hire H-1b workers are outcompeting companies that hire mostly native-born Americans.

And so on. It is possible to find papers that conclude that H-1b workers displace similar native workers, but they’re few and far between.2

How are these results possible? One possibility, put forward by Mayda et al., is that H-1b workers and native-born workers just do very different jobs, so there’s a “low degree of substitutability”. This is similar to the argument that immigrants take jobs that native-born workers can’t or won’t do.

But I think there’s another force at work here: industrial clustering. It’s a well-known fact that companies in knowledge industries — tech, finance, entertainment, biotech — tend to cluster together in cities. Why? When you have an area with a lot of high-skilled labor, high-tech companies will find it easier to hire everyone they need in that area, so they’ll pour investment into that location. This is why Silicon Valley remains dominant in the IT industry despite the Bay Area’s very high costs and dysfunctional governance — it’s where all the engineers live, so companies want to invest there.

The same is true at the country level. If America weren’t home to so many talented software engineers, for example, the tech industry would be much more reluctant to invest there. Software would be relatively easy to sell from Bangalore or Hyderabad; instead, companies make it in San Francisco and Palo Alto, because of their concentrations of talent.

Thus, H-1b workers could actually be reinforcing America’s overall advantage as the place where high-tech companies want to invest. This increased investment naturally benefits native-born tech workers as well.

In fact, there is some evidence for this theory. Glennon (2023) shows that when companies are prevented from hiring H-1b workers, they start investing in other countries instead:

How do multinational firms respond when artificial constraints, namely policies restricting skilled immigration, are placed on their ability to hire scarce human capital?…[F]irms respond to restrictions on H-1B immigration by increasing foreign affiliate employment…particularly in China, India, and Canada. The most impacted jobs were R&D-intensive ones…[F]or every visa rejection, [multinational companies] hire 0.4 employees abroad.

It would be interesting to see studies like this done at the city level, to see the spillover benefits from more H-1b workers living in an area. But this evidence is strongly suggestive of a “hire them here or hire them there” effect of H-1bs. If investment dollars go overseas instead of staying in the U.S., American tech workers are not going to benefit.

Also, Dimmock et al. (2019) find that startups that manage to hire H-1b workers are a lot more likely to have a successful exit. Startup failures pretty obviously don’t benefit native-born U.S. tech workers. And of course there are plenty of startups that wouldn’t even exist without founders who used H-1bs to get into the country, not to mention the beneficial discoveries that wouldn’t have been made (or at least, not in America) without H-1b researchers.

In other words, Elon is exactly right about this:

In fact, Elon should know — he worked in America on an H-1b visa in the 1990s.

(Side note: The fact that Elon has been so pugnaciously insistent here, instead of rolling over for the MAGA base like some other tech folks did, should make people a bit less willing to believe in the “Evil Elon” theory. Calling for more skilled immigration, even in the face of right-wing rage, is a very pro-American move.)

Of course, none of this means that the H-1b program is perfect. In fact, there are at least two reforms that basically everyone realizes would be good. The first is to make H-1b visas more easily transferable, so that foreign workers could hop from job to job more easily without losing their visas. But this probably isn’t nearly as severe as people think. Mithas and Lucas (2010) find that once you control for observable determinants of skills, H-1b workers actually get paid more than similar American workers, not less. That means they’re generally not being forced to do the same job as a native-born worker for lower cost, as some allege.

The second and more important reform is to implement a minimum salary for the H-1b. Right now, some of the available visas get snapped up by low-productivity service-outsourcing companies for low-level employees, instead of being used to hire very high-productivity engineers, managers, etc. That needs to stop, and the way to do this is to only offer H-1bs to workers who will be paid high salaries.

Of course, raising the overall cap on H-1bs would also help this problem a lot. Somehow I don’t think the rabid critics of that H-1b program would like to do that.

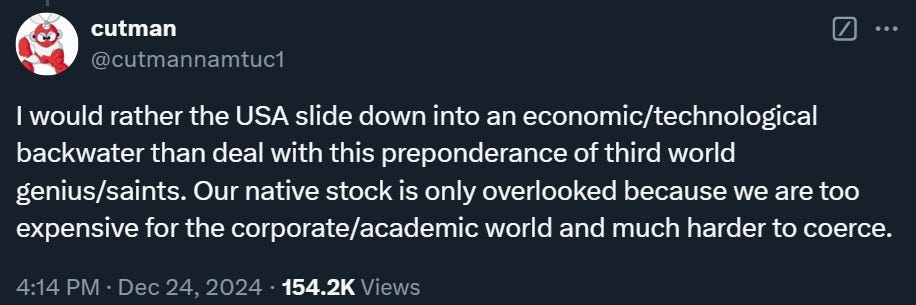

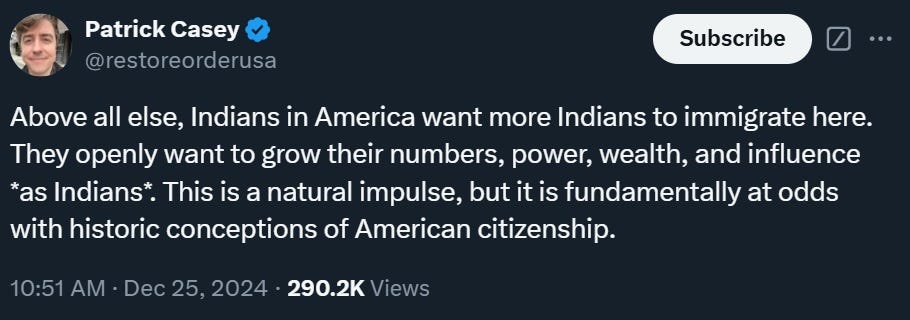

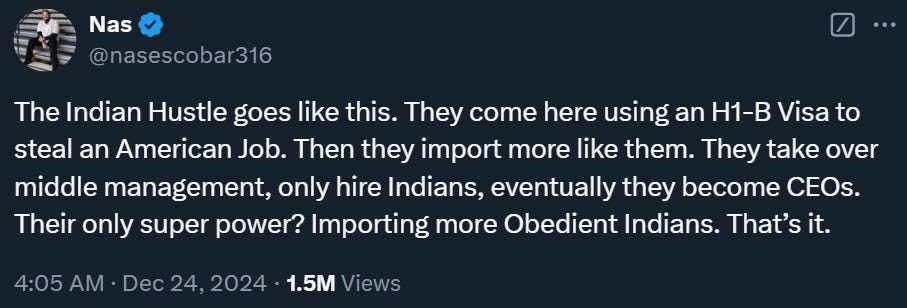

Anyway, the overall point here is that the H-1b program is good on the economic merits — not just for U.S. companies, but for their high-skilled employees as well. But after reading multiple days of right-wing social media backlash against skilled immigration, I’m not so sure the economic merits of the program, or even the economic fortunes of the United States of America, are really what they have in mind. Tweets like this one have been sadly common:

As so often happens, I think what we’re dealing with here is a battle over America’s cultural and racial identity, which some people only feel comfortable talking about in terms of its economic impacts.

The MAGA backlash against Indians is very bad

Over the past two days, I have seen a lot of tweets like this from right-wing X users:

Of course as you can imagine, the comments from pseudonymous rightists were more vicious toward Indians.

The animosity toward Indian immigrants in particular is something I’ve seen with increasing frequency on the nativist right over the past few years. Here’s what University of Pennsylvania law professor Amy Wax said in 2022:

“Here’s the problem,” she said. “They are taught that they are better than everybody else because they are Brahmin elites and yet on some level, their country is a s—hole. ... They’ve realized that we’ve outgunned and outclassed them in every way. ... They feel anger. They feel envy. They feel shame. ... It creates ingratitude of the most monstrous kind.”

And these bigoted attitudes could be spilling over somewhat into everyday society:

We find that 31 percent of Indian Americans believe that discrimination against people of Indian origin is a major problem in the United States — while 53 percent think it’s a minor problem. Measuring respondents’ lived experiences with discrimination reveals that 1 in 2 Indian Americans reports being subjected to some form of discrimination over the previous 12 months.

The rightists who denounce Indian Americans on social media believe that we face a choice between a cohesive nation, with rich social ties cemented by bonds of common heritage, and an atomized nation where cohesion is sacrificed on the altar of higher GDP. They believe that by excluding people who aren’t of America’s noble founding stock, we can restore civic trust, stop people from “bowling alone”, and so on.

This is abject fantasy. Perhaps in a nation like Japan or Sweden, where a sense of homogeneity has been cemented over centuries, and big waves of immigration are relatively recent, something like this could make sense. But the United States has been an immigration-fueled polyglot since its very founding.

No sooner had British Americans created the country than it was inundated by Irish Catholic immigrants, causing vast anti-Catholic backlashes and efforts at large-scale deportation. These had barely died down when tensions began to rise in the late 19th century over the arrival of Italians, Poles, Jews, and other East and South Europeans en masse. Today’s anti-immigrant freakout is the third since the founding.

So if you decide to try to strip down America’s population to its founding stock, who will you include? Do the Italians get to stay? How about the Vietnamese refugees who came in the 70s? Are the Irish part of America’s core population, or papist interlopers? What about a Mexican American whose ancestors came in the 1930s? Where do you draw the line? What about someone who looks entirely Asian but who has one ancestor who sailed in on the Mayflower?

Searching for an ethnicity that represents the “true” or “core” American stock is like peeling back the layers of an onion — when you get to the center there’s nothing left.

In practice, any effort to ethnically purify America will just turn the nation against itself — the battles over Indian immigration on X this week will become a template for our daily lives. If you think dealing with woke people calling you a white supremacist at work in 2018 was annoying, imagine spending all day wondering if the U.S. government will declare your ethnicity peripheral to the American national project. Naturally, you would spend a lot of your time fighting to make sure your ethnicity ended up inside the circle that the purifiers ended up drawing. Daily life would thus be reduced to racial conflict.

Americans do not want this. Yes, a majority voted for Trump, but it was not because they thought he would racially purify the nation. In fact, his victory was driven pretty much entirely by defections of Latinos and Asians from the Democratic coalition. It’s doubtful that those swing voters imagine Trump as an ethnic cleanser.

And I predict, pretty confidently, that Trump won’t be an ethnic cleanser in his second term. He flirted slightly with the idea with his “Muslim ban”, but ultimately backed off. There was, and is, simply no national appetite for converting America to an ethnostate. It’s just a few right-wing activists screeching about their Indian coworkers on social media.

In the old days, when I was growing up, we used to simply call that sort of thing “racism”, and thus exile it from polite society. Behind that taboo were centuries of history of contentious nation-building and self-definition. We learned from experience that a polyglot nation can’t constantly think about who are the country’s true “sons of the soil”, or it paralyzes itself with conflict.

Now, after the 2010s, “racist” is such an overused insult that it’s applied toward basically anything. Social media created a zone of opportunism where anonymous teenagers clawed for status by constantly finding new innocuous things to call “racist”, while progressive activists devalued the term by trying to apply it too broadly. This robbed the word of its power to righteously condemn the kind of people who go on social media and declare that Indian doctors and CEOs are a bunch of third-world mud people who will pollute the blood of our nation. So yes, all the racism against Indians now pouring out of right-wing circles is very racistly racist racism from a bunch of racist racists, but saying that fact is no longer sufficient to make it go away.

But at least some people on the new Tech Right are now realizing what kind of tiger — or perhaps, leopard — they’ve chosen to ride. The Trump movement of 2016 had a reputation for being full of racial-nationalist bigotry for a reason — it might have been exaggerated, but it wasn’t just a progressive fantasy cooked up by newsroom staffers at the New York Times. Now, if you’re a tech founder who supports Trump and spends all day posting on X, your daily life involves your so-called political allies denouncing your Indian friends and cofounders and employees and calling for their mass deportation.

Well, such is politics. Meanwhile, in the real world, Indian immigrants and their descendants are hard at work making America an even better place, and I would very much like them to continue.

In terms of per capita income, they are slightly behind the Taiwanese, who have smaller households.

It’s also not too hard to write down a theoretical model in which H-1b workers displace the native-born. But these models are only as good as the assumptions that go into them, and they don’t tend to include things like clustering effects. In general, when you have theory vs. high-quality data in economics, go with the latter.

It's in the post, but needs to be louder: the alternative to importing more skilled labor is offshoring more skilled jobs.

Every time we open a tech role we are carefully weighing the pros of putting it in the US versus the cost advantages of putting it in India. This is happening at every major company I know. Without skilled immigration the balance will rapidly move offshore. That's what stopping visas will do.

This discourse highlights the anxiety felt by some Americans who I view as very “average” (think IQ around 100 or so) in a rapidly evolving meritocratic landscape.

The central question becomes how these “average” individuals can secure a meaningful future when economic success appears to hinge on specialized knowledge, creativity, and higher intelligence. If America’s prosperity relies on constant innovation and a high bar for ability, what does that mean for people who don’t meet that standard? This tension—between meritocratic ideals and the realities of the world it creates—is what the conversation is really about.

And remember, envy drives the world.