Fixing Japan's broken corporate culture

Some ideas for boosting workplace productivity.

This is the third of a series of posts about Japan (which I’m writing while in Japan). In the first post, I talked about Japan’s surprisingly low living standards, and suggested a cash-based welfare state to correct inequality. But more is needed, because Japan’s per capita GDP is just too low. In the second post, I offered a bunch of ideas for how Japan could boost GDP growth even in the face of an aging population. Ultimately, growth means raising the country’s oddly low levels of productivity:

Productivity is a function of a bunch of things, and the ideas in my previous post — exporting more, helping startups get big, and so on — will help. But a big factor is the country’s broken corporate culture. Although Japanese culture is extremely dynamic in many ways, the patterns of work, hiring, promotion and pay have remained stubbornly stuck in the past.

This is, of course, well known to essentially everyone in Japan, but here’s a brief recap for everyone else. Japanese companies still mostly hire full-time salaried employees directly out of college, instead of in the middle of their careers; this leads to very little job-hopping. Promotion and pay at most companies are still based mostly (or entirely) on tenure at the company, so for most workers there’s little incentive to do a good job and little hope of bettering one’s economic situation.

This keeps young people out of management roles, starving companies of new ideas and making it hard for them to adapt to new technologies and new market opportunities. In a 2017 paper, Ikeda, Inoue & Watanabe examine Japanese corporations and find that “entrenched managers who are insulated from disciplinary power of [the] stock market avoid making difficult decisions such as large investments and business restructures.” It also keeps women out of management roles, cementing the gender gap.

Instead of the incentive of greater pay and promotions, Japanese companies try to get their workers to produce more by constantly monitoring them. Most offices are open-plan affairs, like this:

In this environment, it’s very important for every employee to appear to be working all the time. But that doesn’t mean work is actually getting done. Some people work incredibly hard, but many simply invent useless busy-work for themselves to do all day. The most extreme anecdote I’ve heard involved people copying records from computers to paper and back again.

Because so little actual work is getting done each hour, companies try to get their workers to stay at the office til all hours of the night. This burns them out, robs them of the chance for a family life, and even causes some suicides. It tires them out and makes them less productive when it comes time to actually get real work done. And this is especially hard on women, who are still forced to do a disproportionate amount of the child care and housework in Japanese households.

Anyway, that’s the basic situation. If you want to read more, there are plenty of articles out there. Today I want to talk about how to fix the situation. Japan’s government and many of its large companies know this is a problem, and have been taking some steps in recent years, but much more needs to be done.

What the government has done already

The government has attacked the problem of unproductive corporate culture over the past decade, in two major ways. First, it has encouraged greater control of companies by shareholders and outside directors. Second, it has tried to discourage long working hours. These are both good initiatives, though by themselves they won’t fully solve the problem.

First, let’s talk about shareholder control. In the U.S., the “shareholder revolution” took away power from entrenched corporate managers in the 70s and 80s, but in Japan this never really happened, so a lot of executives just tend to sit their and build their comfortable empires instead of focusing on profitability. If management becomes subject to more shareholder control, the theory goes, it will be forced to focus more on profitability — and therefore on efficiency. There is evidence to support this; Ikeda et al. do find that “when managers are closely monitored by institutional investors and independent directors, they tend to be active in making difficult decisions.”

To further shareholder control, Japan’s Financial Services Agency introduced a corporate governance code in 2015. Though this code is nonbinding, Japanese companies often do what the bureaucracy tells them they ought to do, especially when called upon to regularly report their progress. The code has been updated several times; the most recent set of updates enhances board independence and strengthens reporting requirements regarding the code’s pro-diversity provisions. Interestingly, the diversity provisions target three groups:

Women

Foreigners

Mid-career professionals

This code is good. It has successfully increased the number of outside directors. This is probably a factor in the record profit margins of Japanese companies:

And the code may be a force behind the increasing hiring and promotion of women in Japan:

But as you can see from the chart for female managers, the improvement is slow going. The seniority-based promotion system means that women hoping to become managers will have to wait decades, even at companies that are committed to gender equality at the lower levels. Applying diversity provisions to mid-career professionals may help address that, but more is needed (more on that later).

In addition to corporate governance, Japan’s government has been attacking long work hours. The idea here is that if companies have to send workers home earlier, they’ll stop thinking they can substitute long hours for productivity, and that this will make them shift their focus from time input to work output.

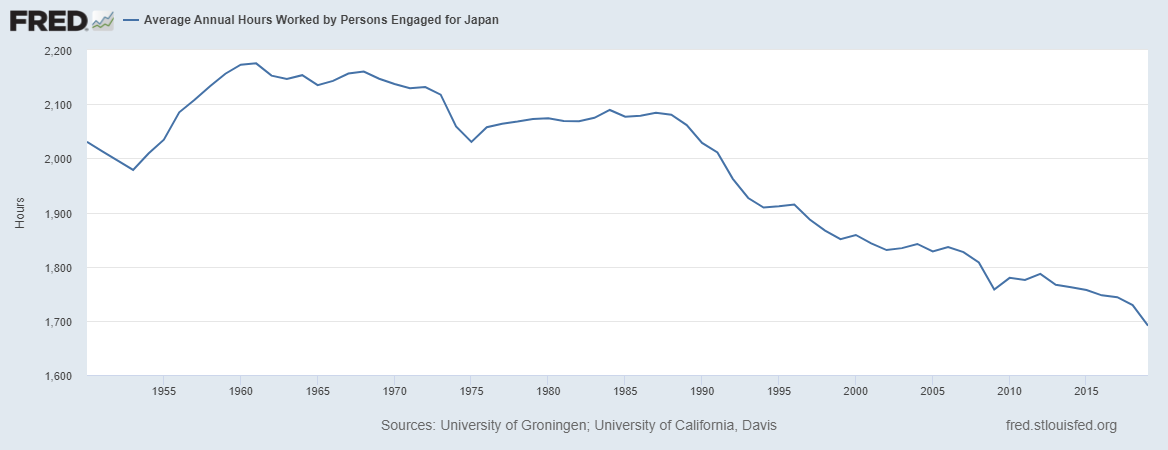

To this end, the government enacted a major work style reform bill. This bill capped overtime hours, raised overtime pay requirements for smaller companies, encouraged companies to make employees use their paid leave, and required employers to “make efforts” to let workers get enough rest. The result has been a slight acceleration of a long downtrend in annual work hours:

And some big companies, like Panasonic, have even adopted four-day workweeks.

This approach has two basic shortcomings. First of all, it’s hard to verify whether employees are actually working less, or whether companies are just keeping more work hours off the books. And second, it will only succeed if shorter working hours actually push companies toward greater efficiency. If companies keep the same unproductive corporate culture but just cut wages, leisure time increases, but GDP growth and material living standards stagnate.

So the government needs to do more to encourage a shift to a productivity-focused work culture. Here are three ideas.

1. Encourage mid-career job changes for managers

This is really the key to changing the whole culture. Japan doesn’t really have “lifetime employment” anymore — you can definitely get laid off. But basing promotions and pay entirely on seniority ossifies organizations utterly, because it means the same old guys are always in charge. And it also prevents ideas, technologies, and best practices from flowing between companies, because employees who switch employers are a very important vector for the spread of ideas.

Izumi & Kwon (2015) find evidence of this. In the U.S., a change of CEO usually increases corporate profitability, while in Japan it doesn’t; this is because Japanese CEOs are usually promoted from within the company, while American CEOs are usually hired from outside.

There has been a little progress on this front in recent years. Mid-career job switching has doubled, but is still at a low level. And job-hopping has become somewhat more effective at boosting wages for those who do switch, which suggests that these hires are being used to drive productivity. And Japanese companies say they want to do more mid-career hiring:

So far, though, the increases have been modest. And many of the job-hoppers have been the low-paid, non-management track contract workers and part-time workers, instead of the full-time management track workers who really matter for corporate culture.

Hopefully the FSA’s inclusion of mid-career hires in diversity reporting will have an effect. But there are a number of things the government can do in addition to reporting, exhortation, and shaming.

First, the government should consider deploying tax incentives for mid-career hiring. Companies should get a tax break for the first one or two years of a full-time worker’s job. This means that if you hire new full-time people a lot, you get to pay much lower taxes. The tax break should be proportional to the worker’s salary, so switching out top management will be the biggest money-saver.

Second, the government should partner with job-finding sites like Wantedly to formalize and publicize the practice of hiring outside managers. A publicity campaign showing exactly how successful mid-career management hires are done, and showing smaller companies exactly how to do it, would help the idea become a new universal Japanese norm.

2. Encourage work-from-home

Japan, like every country, experimented with work-from-home policies during the pandemic. But unlike in the U.S., where WFH had generally positive results, Japan really struggled with it. A survey by the think tank RIETI showed that Japanese workers felt they were less productive at home. Some of the workers cited corporate rules dictating what they were and weren’t allowed to do at home, but the most commonly cited figure was lack of communication with coworkers.

To me, this suggests that Japan’s ossified corporate culture has simply taught workers to work in an inefficient way, with too little individual input and too much cross-checking of others’ work — a model fit more for a factory (where Japanese productivity is still top-notch) than for an office. Japanese workers simply aren’t used to taking some of their work home with them, as Americans are.

Instead of abandoning work-from home, therefore, I think Japan should double down. The government can encourage WFH with tax breaks, reporting requirements, and publicizing of best practices. Of course if productivity suffers as a result the experiment should be curtailed, but my guess is that over time, WFH will teach Japanese workers how to do stuff for themselves without constant meetings and without looking over each others’ shoulders.

3. Let failed companies fail

This is the toughest one, and certain to be the most controversial, but it’s essential. The Japanese government has a very bad habit of stepping in to put failed companies on life support.

In the post-bubble 90s, Japan’s big banks propped up tons of “zombie” companies with cheap loans. For a classic primer on how this worked and why it held back economic growth, read Caballero, Hoshi & Kashyap (2008). For a deeper dive on the mechanics of how banks did this, read Peek & Rosengren (2003). But basically, this made the big Japanese banks get weaker and weaker, as you’d expect. Finally, the Japanese government stepped in and bailed out the banks.

In more recent years, the government has largely dispensed with using the banks as an intermediary, and simply stepped in to do the bailouts itself. I wrote a pair of articles about this for Bloomberg in 2015 and 2016, so I’ll just quote myself a little bit:

The most glaring example is the Enterprise Turnaround Initiative Corp. of Japan, or ETIC. The company, which is 50 percent owned by the Japanese government, was created in 2009 to buy the debt of companies that were in financial distress due to the global financial crisis. But the crisis passed, and ETIC remained. Recently it was rolled into a larger organization called the Regional Economy Vitalization Corp. (REVIC). And before that, in 2003 through 2007 when there was no crisis at all, the Industrial Revitalization Corp. of Japan served a similar purpose…

For example, in 2011, REVIC bailed out auto prototype-maker Arrk Corp. after that company’s “aggressive M&A strategy backfired,”…The Innovation Network Corp. of Japan (INCJ), another government-sponsored enterprise charged with carrying out industrial policy, recently bailed out failing semiconductor giant Renesas.

and

The Innovation Network Corp. of Japan offer[ed] to bail out [electronics giant] Sharp [in 2016] with an injection of 200 billion yen (about $1.7 billion). INCJ, which is funded by industrial giants but backed by government guarantees, will keep Sharp’s struggling LCD division alive and merge it with a rival, Japan Display Inc., itself a consortium of large corporations.

Nor is this a thing of the past. Just this week, Bloomberg reported that a Japanese state-backed fund is exploring a bid for Toshiba, an electronics and infrastructure giant that once bestrode the corporate world like a colossus.

It’s understandable that Japan’s government would want to preserve people’s jobs and minimize unemployment and unrest (and support the stock market). But if you simply nationalize your companies when they fail, you’ll get two big long-term problems. First, your economy will be filled with unproductive zombie state-owned enterprises with little incentive to improve productivity, just as it was in the 90s. Second, the managers of companies that are still private will know that even if they fail utterly, there’s a decent likelihood that the government will step in and let them keep their little corporate empires. So they have much less incentive to raise productivity.

This will simply not do. There need to be real consequences for managers who hoard power, dole out promotions and salary based entirely on seniority, keep women out of good jobs, and require long punishing hours of low-productivity busy-work. Government reporting requirements and tax incentives are helpful, but at the end of the day, capitalism has to mean that private companies can fail.

Of course that doesn’t mean companies should never get government bailouts. The first year of Covid was an emergency that overrode the long-term imperatives of capitalism. But Japan’s government has allowed a string of such emergencies — the 2008 financial crisis, the 2011 tsunami, and Covid — to put it in a mindset of permanent emergency. At some point, the government has to realize that the world is an uncertain and dangerous place, crises happen, and corporations ought to be robust, flexible, and nimble enough to survive them.

Thus, Japan’s government should turn these bailout funds into resolution funds. After acquisition, the companies should either be quickly dissolved or sold off to private equity firms. This can generally be done within a single year.

Of course, this will put people out of work. This is where mid-career hire promotion comes in. The government can use tax incentives and partnerships with private job-finding sites to help the employees laid off by corporate failures to find new jobs at healthy and growing corporations as quickly as possible. Top managers at failed companies will probably have to take lower-level positions at other companies, but that has to be the punishment for refusing to improve corporate culture.

In sum, Japan is making incremental progress improving its corporate culture, but making faster progress will involve sticks as well as carrots. But the alternative to wielding the stick is a long genteel decline into the ranks of the middle-income countries. That’s not an acceptable outcome. Japan’s old corporate culture has outlived its usefulness, and for the good of the nation it must change.

It really is astonishing that in spite of this corporate culture, Japan produces a ton of impressive technical innovations. Imagine if they could actually shake themselves loose from all the make-work... their per-capita GDP would probably leap up to parity with countries like Germany (which excels in a lot of the same areas).

One could hope that the COVID work-from-home experience might've shaken things up a bit in terms of the need to appear in the office all the time? But probably not. Even in the US, bad managers have already pushed toward forcing people back to appearing in person and looking busy. :-/

Interesting post!

Season 4 of Aggretsuko dealt with these issues by having an outsider, Himuro, take over the company as CEO. He shakes things up, rewarding Haida for automating the accounting stuff, but also tries to make lots of layoffs* and pressures Haida into cooking the books to make the company's profits look good. Himuro is portrayed as ruthless and psychopathic - he admits to viewing workers as disposable - but also innovative and candid. By contrast, the original CEO and other managers think of the company as a "family" (which, ofc, belies the long hours and abuse that Retsuko and her coworkers have had to endure), so they're reluctant to make layoffs. I think the writers might have written Himuro this way because they're suspicious of changes to a more American-style, profit-driven corporate culture.

* As Himuro himself says, it is difficult to actually fire people in Japan, so he "fires" them by pressuring them to quit voluntarily.