White Americans as a normal minority

Creating a stable multiracial nation is a tricky thing to do.

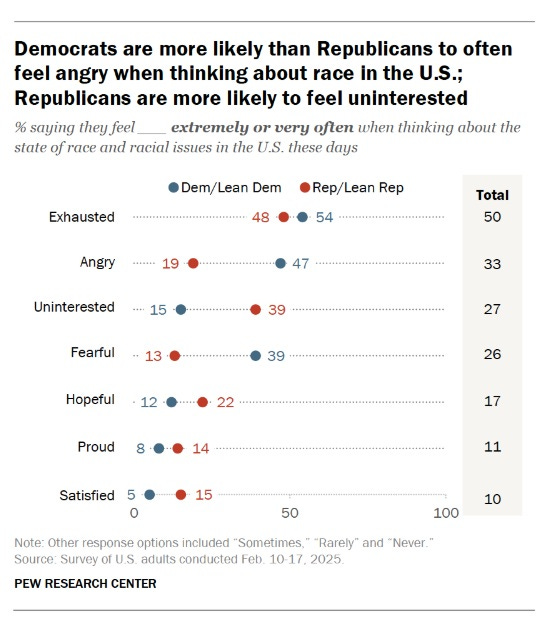

I haven’t written about racial issues in a while, and it’s not hard to see why. After a decade where it often seemed like Americans talked and thought about nothing else, I think people are generally tired of the topic. In fact, I think some of the big shift of minority voters to the GOP in 2024 can probably be attributed to progressives’ habit of painting every political issue in racial terms — for example, D’Urso and Roman (2024) found that Hispanic voters who encountered the word “Latinx” became more likely to vote for Trump. And even back in 2022, well before Trump was elected, American media and academia had already started discussing race less and less, as the “Great Awokening” wound down. The BLM movement all but disappeared, and Kamala Harris’ 2024 campaign generally avoided the appeals to racial justice that had been the centerpiece of her 2020 primary effort. In a recent Pew poll, the dominant feeling that both Democrats and Republicans expressed toward the issue of race in America was “exhausted”:

But every once in a while, I think it’s important to circle back to the issue, because it’s important for our national future. As Gary Gerstle writes, every country conceives of itself not just in terms of civic institutions and national symbols, but also in terms of identity — the question of “Who are the Americans as a people?” is fundamental. Without a broad consensus on who counts as a real American, it becomes a lot harder to exercise collective action via the democratic process; we become an “artificial state”, where people are more wedded to the interests of their subgroup than to the nation as a whole. In that environment it becomes a lot harder to provide public goods like infrastructure, research, and even national defense, because everyone worries that their own tribe won’t receive the bulk of the benefits.

And while Americans in general are tired of racial issues, the second Trump administration is focusing far more on race than the first. In the 2010s, a lot of people assumed that Trump’s movement was all about white identity politics, but beyond occasional rhetoric about how “our ancestors tamed a continent” and some nasty swipes at “shithole countries”, there was very little in Trump’s first term that was explicitly targeted toward helping white people as a group. That has changed in his second term. Under Trump, the Department of Justice has shifted its focus toward investigating or prosecuting institutions for anti-white discrimination. For example, the DoJ is investigating the city of Chicago:

The U.S. Department of Justice has opened a civil rights investigation into…whether the city has habitually violated Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of race.

And the DoJ is investigating Harvard Law Review:

The Trump administration said it would investigate whether Harvard University and the student-run journal, the Harvard Law Review, violated civil rights law when editors of the prestigious journal fast-tracked consideration of an article written by someone of a racial minority…The administration argued the school and law review journal may have violated Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by allegedly engaging in “race-based discrimination”.

And of course there’s Trump’s cutoff of federal grants to Harvard University over alleged racial discrimination against whites and Asians. Trump is having the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission probe Harvard for anti-white and anti-Asian hiring discrimination:

The Trump administration is investigating whether Harvard University discriminated against white, Asian, male or heterosexual workers in its hiring and promotion practices…In a six-page document, the charge notes Harvard’s share of tenured white male faculty dropped from 64% to 56% from 2013 to 2023. The share of tenure-track faculty who are white men dropped from 46% to 32%…Lucas alleged the data signal “an underlying pattern or practice of discrimination” based on race and sex and “there is reason to believe” discrimination is continuing.

Ending DEI programs has been a major focus of the administration’s efforts to reform the U.S. civil service. And Trump has used government leverage to pressure private companies to end their DEI programs as well.

The Trump administration’s desire to protect white people even extends beyond America’s borders. Despite his general opposition to humanitarian immigration, Trump has fast-tracked the admission of white South African refugees fleeing racial discrimination in their homeland. And he recently castigated the President of South Africa for anti-white discrimination.

In other words, despite Trump’s increasingly multiracial electoral coalition, he has become the champion of white people in a way that he never really was in his first term.

Plenty of progressives are mad about this, of course. Around 70% of the DoJ’s Civil Rights Division has resigned in protest over the department’s change in focus:

[N]ow, current and former officials say, there's a sense that the division is weaponizing the country's civil rights laws against populations it's supposed to be protecting. They say the abandonment of the traditional mission has been devastating. One official recalled attorneys walking around the hallways in tears or sobbing through meetings.

Personally, I’m ambivalent about Trump’s efforts. On one hand, it’s possible to see all of this as part of the New Right’s crusade to reorient America, Europe, and the Anglosphere away from Enlightenment liberalism, toward a concept of “Western Civilization” that privileges European cultural and genetic heritage above all else. That reorientation would be a foolish, even suicidal move. And it certainly fits with the administration’s hostility toward immigration, which I think is an extremely self-destructive policy.

But on the other hand, I think it’s also possible to see Trump’s anti-discrimination lawsuits and investigations as the beginning of something healthier — a shift of white identity politics toward a focus on individual rights and away from traditional strategies of “white supremacy”. To put it bluntly, white people are in the process of becoming a minority in American society, and in general it’s better for minorities to defend their interests through the legal system and the framework of individual rights and non-discrimination than through collectivist mass politics.

In America’s multiracial future, white Americans will be one minority among many

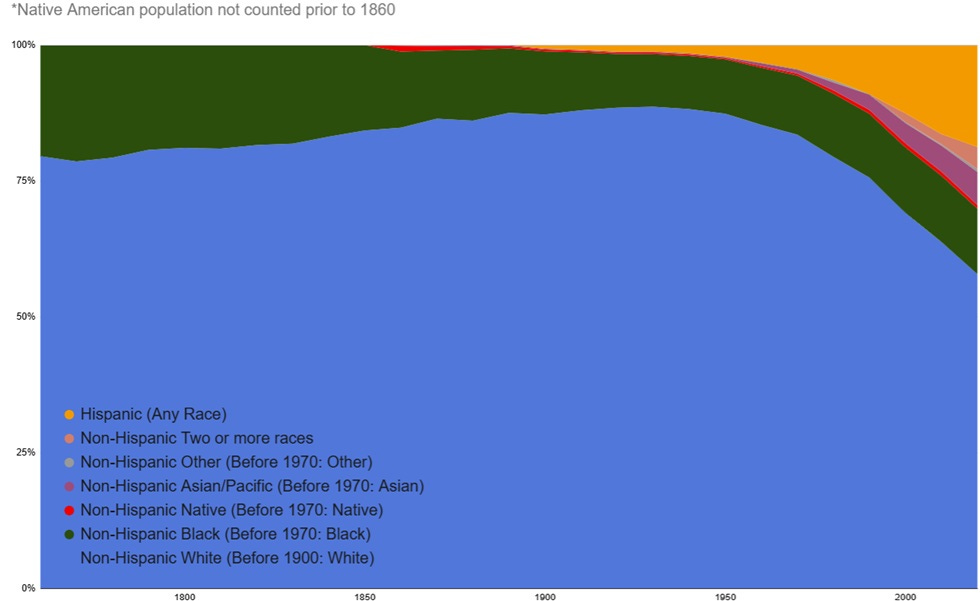

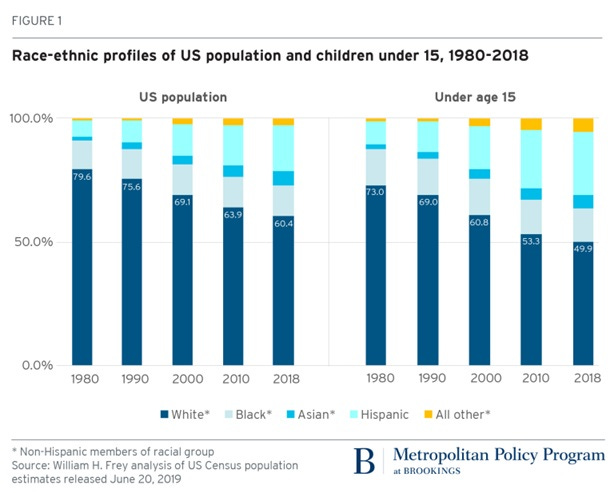

White Americans are not yet a minority in America. Non-Hispanic white people still accounted for almost 60% of the population as of the 2020 census:

And if you count Hispanics who identify as white, the percentage rises to over 61%.

But this slim majority is fading fast. All the way back in 2018, white people were already a minority of Americans under the age of 15:

It’s now estimated that white Americans will become an absolute minority 20 years from now, and that Gen Z will be the last majority-white generation.

What’s more, in many regions of the country, white people are already a minority. California is less than 35% white. Texas is less than 40% white. White people will become a minority in Florida in the next few years. If you break things down by city, there are even more places where white people are a minority and have been so for a long time. And of course, as white people’s numerical majority shrinks nationwide, there are inevitably more and more institutions — companies, university departments, social clubs, etc. — where they’re in the local minority.1

This raises the crucial question: As a minority, how will white Americans behave? Most of the time, the answer is: Just like anyone else. The political upheavals of the 2010s pushed Americans to view every aspect of life through the lens of race, but on the ground — in local communities, organizations, friend groups, and families — it’s usually not the most salient thing. Interracial marriage is still on the rise, as are interracial friendships — especially among young people. What’s more, the percentage of Americans who identify as multiracial or mixed-race is rising very rapidly, which tends to blur traditional racial boundaries.

The sociologist Richard Alba has argued — persuasively, in my view — that these trends, taken together, will decrease the overall salience of race in America. He predicts that most Americans will blend into a multiracial “mainstream” where most people simply don’t think about their racial differences very much, or don’t place great importance on those differences when they do think about them. (Personally speaking, this already applies to my own social circle.)

But there will inevitably be times that race matters. There will be cases of discrimination in employment, promotion, business deals, school admissions, and so on. Anti-black, anti-white, anti-Asian, and other forms of racial discrimination will all exist in different places at the same time. There will be politicians who make racial appeals to try to get elected, and NGOs and lobby groups that claim to represent — or quietly think of themselves as representing — the interests of specific races. There will be explicitly and implicitly race-based clubs at universities, schools, and companies. And there will be people on social media who try to stir up racial conflict, suspicion, and division in order to get attention and to satisfy their own sadistic instincts.

When white Americans were the overwhelming majority in America, those situations sometimes occurred, but they weren’t particularly threatening. In 1993, there were very few jobs where white people had to worry about facing racial discrimination — and if you did happen to encounter one of those few, you could easily just go somewhere else instead of raising a big stink.

But as white people become a minority, the danger of anti-white discrimination — or at least, the perception of danger — inevitably grows. Many (most?) white people will think nothing of interviewing at a company where the boss or the hiring manager is black, or Asian, or Hispanic. But some will worry: “What if this person in power thinks there are too many white people at their company? What if they’re mad at white people in general over slavery, or segregation, or the Chinese Exclusion Act? What if I just don’t remind them of their college buddies?”

In the political arena, the worries will be: “What if the Democrats don’t represent me? What if the government is trying to correct racial wealth disparities by making me poorer and less employable?”

These are the worries that black, Asian, and Hispanic Americans have had to endure since time immemorial, and will continue to endure. Now, white Americans will have to endure them as well. That’s not a good thing — it’s simply an inevitable challenge of living in a multiracial society. Racial trust and harmony don’t simply appear out of thin air; they must be built over time.

A key question is: How will white Americans deal with those risks and worries, now that they’re becoming a minority? The answer to this question could be crucial to the future of the country.

One possible approach, of course — and one that many will take — is to do nothing. If you believe that white privilege is ontologically baked into the DNA of America, and needs to be corrected with active discrimination — or that statistical wealth and income gaps ought to be remedied by discrimination at the individual level — then you might accept diminished economic opportunity for yourself as the inevitable cost of antiracism. To some, this will feel like a virtuous, responsible, moral choice.

But many white people will not take this road. Many don’t accept the dubious idea that a country can have racial privilege in its “DNA”. Many will feel it’s unfair that they should be individually punished in order to correct some statistical disparity that they personally had no hand in creating. Others will simply want to fight for their own economic interests, without thinking too hard about the moral justification.

So the question is: What do those people do? In general, I think there are two types of strategies by which minorities try to advance their interests: individual strategies, and collective ones.

Individual strategies for minorities are healthier for a country than collective ones

Individual strategies are when minorities fight for their rights as individual human beings, emphasize their individual humanity, or attempt to achieve success and integration as individuals. They might include:

Anti-discrimination lawsuits

Humanization campaigns

Media representation

Desegregation

Boundary-breaking

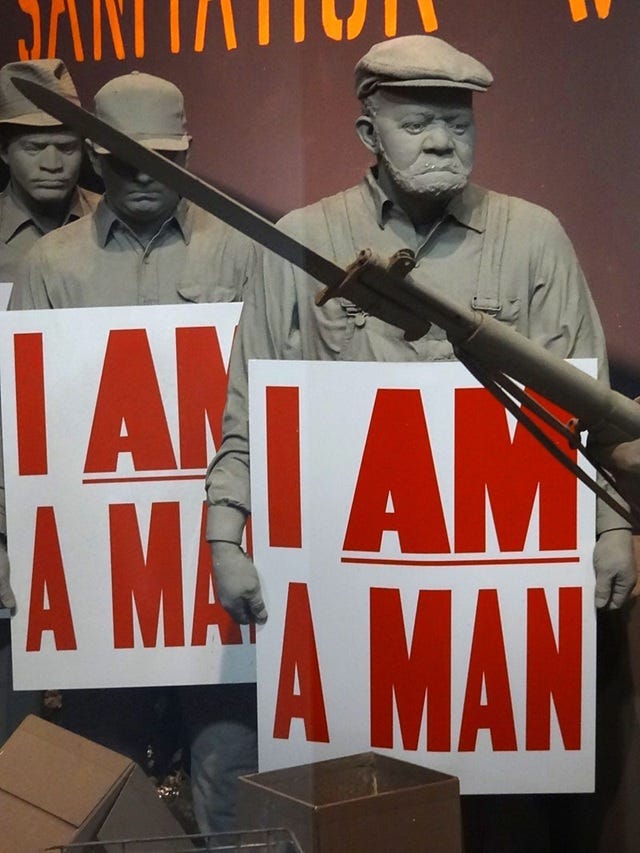

A good example of a humanization campaign is the “I AM A MAN” slogan used by many of the civil rights activists in the 20th century:

Sojourner Truth’s famous “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech is another example. And of course the most famous example is the MLK line that “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” These rhetorical approaches emphasized common humanity at the individual level as a way of combatting systematic discrimination against minorities.

Media representation is another individual strategy. When more Asian people are in the movies, it humanizes Asian people to audiences who might not have Asian friends. Barrier-breaking — the first black Supreme Court justice, or the first black Major League Baseball player, etc. — emphasizes individual achievement. And desegregation gives individuals of various races the chance to mingle and form friendships, business relationships, families, and so on — leveraging the contact effect to make the general public more favorable toward members of a minority group, while also promoting interdependency and positive-sum economic interaction.

Anti-discrimination lawsuits are perhaps the purest example of an individual strategy. They’re based on the idea that merit and opportunity should be decided purely at the individual level, with no regard for group membership. Minorities in America have used this strategy quite extensively.

Collective strategies for minorities are very different. These are when minorities band together in organizations to fight for their mutual interests. These could include:

Racial lobby groups and advocacy organizations

Self-segregation

Discrimination against non-members of the minority

“Power” movements emphasizing racial solidarity and identity

Intercommunal violence

The first of these collective strategies is pretty benign — for example, few would argue that the NAACP or the Congressional Black Caucus are any kind of threat to national cohesion.

When you start getting into self-segregation and discrimination against outsiders, things get more dicey. Few Americans raise a stink when black people form black-themed clubs, or theme dorms, or support groups at work. And although some people grumble about Iranian or Armenian or Italian immigrants preferentially doing business with others of their ethnic group, everyone kind of recognizes that this sort of thing is inevitable. But too much of this defeats the project of integration, so American law prohibits various kinds of self-segregation and anti-majority discrimination — at least in principle, if not always in practice.

“Power” movements, like the Black Power movement of the late 1960s and 1970s, make people a little more uneasy, and with good reason. At the political level, racial bloc voting can make it very difficult to provide public goods, because each bloc usually demands benefits that flow exclusively to its own members, instead of things like infrastructure, research, and defense that benefit the population as a whole. Essentially, racial blocs act like nations within a nation. There is some economic research showing that the artificial borders drawn by European colonialists ended up encouraging ethnic bloc politics in Africa, and holding back many African countries’ development.

But the biggest problem with “power” movements is that they can often raise the specter of intercommunal violence:

“Intercommunal violence”, also called “communal violence”, is a sanitized term for race war. Examples from American history include the race riots of 1919, some of the riots of the 1960s, and the L.A. riots of 1992. But these pale in comparison to things like the Partition of India, or the Rwandan Genocide. In the extreme case, intercommunal violence is the worst thing that can happen to any human society.

Just to be clear, I don’t think America is headed for a race war or genocide. But the Trump administration’s anti-immigration push feels like a collective strategy — a way of racially engineering the American population so that the white minority is less outnumbered.

Most Americans who want a tougher stance toward immigration probably don’t think of it as racial population engineering. Many see it as a way of preventing disorder and enforcing the people’s democratic will regarding who gets into the country and who doesn’t. Many are worried about the strain on social services, or — rightly or wrongly — about job competition. Certainly, it seems extremely unlikely that the many Hispanic Americans who support Trump’s immigration policy want to engineer a whiter nation.

But to the New Right, anti-immigration policy is explicitly about barring the admission of people who they feel don’t uphold Western Civilization. Around last Christmas, there was a tremendous fight on X between the Tech Right and the New Right over Indian immigration. The former, led by Elon Musk, argued that skilled Indian workers are crucial for American prosperity. The New Right countered with some economic arguments, but also argued that Indians are unassimilable aliens who want to take over America. Extreme anti-Indian viewpoints became commonplace on the platform:

It wasn’t just the gutter element of social media, either. Amy Wax, a law professor, has made statements declaring Asians as undesirable:

In the podcast Wax asserted that most Asian Americans are Democrats and questioned whether or not “the spirit of liberty beat in their breast”.

“As long as most Asians support Democrats and help to advance their positions, I think the United States is better off with fewer Asians and less Asian immigration,” Wax said.

This kind of xenophobia is very bad for America — not just economically, but in terms of social cohesion, everyday harmony, and political efficacy.

As white Americans transition from majority to minority, there’s a danger that many will turn to collective strategies like racial population engineering. That’s especially dangerous during the transition period, where there’s the feeling that immigration restrictions, mass deportation, and so on could potentially tip the racial balance and keep white people in the majority for a while longer.

And if the effort succeeds, it could tempt rightists to contemplate revoking birthright citizenship retroactively, in order to mass-expel the children and grandchildren of illegal immigrants. At that point, we’d be in full “ethnic cleansing” territory. I don’t think there’s much chance that will ever happen, but simply suggesting it would reduce national unity, impair racial harmony, and encourage racial bloc politics in America.

Nor do I look forward to a future where white Americans engage in the kind of violent collective minority behavior that typified the Black Power movement half a century ago. I do not want to see a white equivalent of the Black Panthers marching through the streets with guns, looking for trouble. I do not want America to become Northern Ireland.

Instead, what I want white Americans to do, when they feel that their rights have been infringed and that they have been discriminated against, is to sue in a court of law.

Recently, Wil Reilly, a conservative black commentator, tweeted:

He’s very right about not needing a fascist revolution, of course. But in fact, there already is a law barring discrimination against whites and Asians. It’s called the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The act bans all racial discrimination in employment and other areas of public life, without naming any specific races. Thus, it protects white people against racial discrimination.

In fact, quite a number of white people have won lawsuits against discrimination under the Civil Rights Act. In 1976, some white freight workers successfully sued their company for firing them while refusing to fire a black employee who committed similar offenses. In 2009, some firefighting applicants sued the city of New Haven, Connecticut for throwing out the results of a test on which white candidates did better. Even under previous presidents, the EEOC devoted some of its effort to cases of anti-white discrimination.2

Winning discrimination lawsuits isn’t easy, including for black plaintiffs, because the burden of proof is pretty heavy. But the ever-present threat of such lawsuits forces a lot of organizations to be very careful about discrimination. And so if it becomes widely known that white people can sue and win, discrimination against white people will become much less likely.

And crucially, knowing that the law is on their side will dissuade many white people from trying to take the law into their own hands. Once they know that their nation protects their individual rights just as strongly as it does the rights of black or Hispanic or Asian people, white people will be less likely to contemplate going outside the bounds of the law, seceding from the nation, overthrowing the government, or other desperate collective measures.

Thus, while I think the Trump administration is doing some very bad things when it comes to race, I think the push to sue for anti-white discrimination is a good thing. Whether or not it’s the most efficient use of government resources, it will have the effect of getting out the message that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 protects white people too, and that they can just sue. That’s something that I think is not yet widely understood, and needs to be.

A multiracial nation is a challenging but rewarding project. Barring the breakup of the country or the application of unthinkably horrific mass violence, white people’s transition to minority status is now inevitable; the only question is what kind of nation this will create. And I would argue that the best possible future is one in which each and every member of every American minority knows that the law of the land protects them and upholds their rights as American individuals, without regard to their race.

I view that understanding as a prerequisite for America to start building a more durable shared national identity that’s not based on ancestry or skin color. In the long run, that’s how America wins.

On top of all that, there’s evidence that a majority begins to feel like a minority well before it actually becomes on. It’s very likely that the advent of wokeness on social media made many white Americans feel more like minorities than they had before.

These are officially under the rubric of “reverse discrimination”, but in the age when white people are a minority, I expect the word “reverse” to fall by the wayside.

Honestly, when I heard that 70% of the Civil Rights division's staff resigned over the choice to start suing on behalf of white plaintiffs, my immediate reaction was "good riddance". People who think anti-discrimination laws should be selectively enforced on behalf of their favored ethnic groups -- especially if they're in the position to decide which cases to enforce -- are some of the most corrosive elements to the entire project of national integration.

Of course, it may very well be that Trump is simply going to replace them with the exact same kind of person, just with a different set of favored ethnic groups. I really wish it didn't feel like I'm being asked to vote for two parties full of racists who simply disagree on who to target.

fwiw, my kids view themselves as pretty post-racial and find all the haranguing about race really annoying