What America needs to do now on national security

The Ukraine-and-TikTok bill is a good start. Here are five more things we need to work on.

For those who aren’t aware, the U.S. Congress just passed — and Biden signed — a major national security bill. The bill has four main provisions:

$61 billion for aid to Ukraine (including $13 billion to re-stock U.S. military supplies that were previously donated)

$26 billion for Israel and Gaza (including $9 billion for humanitarian aid to the Gazans and others)

$8 billion for aid to Taiwan and other Indo-Pacific allies

A measure to force the Chinese company ByteDance to sell TikTok or else shut down operations within 270 days

I’m actually pretty surprised this bill passed, for two reasons. First, Mike Johnson, the Speaker of the House, had stalled Ukraine aid for quite some time, under pressure from the MAGA movement. Second, the Senate looked like it was going to stall the passage of TikTok divestment. But suddenly, both obstacles seemed to evaporate, and the bill passed. The most likely reason, from what I can tell, is that Congressional leaders saw intelligence briefings that made them realize that A) TikTok is definitely acting as both propaganda and spyware for the CCP, and B) Putin’s territorial ambitions in Europe go well beyond Ukraine.

Although I don’t agree with absolutely everything in this bill, the fact that it passed is a very good sign. It means that our leaders are, slowly and reluctantly, waking up to the magnitude of the overseas threat that America and its allies face. The Ukraine aid shows that although Russian propaganda has subverted much of the MAGA movement, there is still a bipartisan majority that is willing to stand up to Putin. The Taiwan aid, though far too small for my liking, shows that the U.S. is starting to realize the danger of an Asian war. And even though it will certainly be challenged in court, the TikTok divestiture provision suggests that the U.S. is not completely comfortable with the idea of its mass media becoming the instrument of hostile totalitarian governments.

That all represents progress. But it’s only a glimmer of progress, because our major national security dilemmas remain unsolved. We need this bill to be the beginning of a more serious attitude toward national security, not simply a stopgap measure that allows us to forget about security and go back to arguing about culture wars.

Here are what I think our five top priorities should be:

1. Rebuild the U.S. defense-industrial base

This is the most essential thing. The Allies won World War 2 because of American manufacturing capacity; thanks to decades of divestment, anti-manufacturing policy, and offshoring, that capacity largely no longer exists. I’ve written two posts about this, and I plan to write a lot more, because I think it’s hard to overstate the magnitude of the danger the disappearance of the Arsenal of Democracy represents to the rest of the world:

The U.S. is now basically incapable of making large numbers of naval vessels, missiles, or artillery shells, and we haven’t yet developed the ability to make large numbers of drones (which are becoming increasingly central to modern warfare).

The shipbuilding problem is especially acute, and people are starting to wake up. Here’s an article in the WSJ from February, entitled “China’s Shipyards Are Ready for a Protracted War. America’s Aren’t.” Here are similar articles from Business Insider and the U.S. Naval Institute, to cite just a couple. But while the media is starting to get a sense of urgency, the Navy itself still seems to be in damage control/spin mode, canceling briefings in order to avoid having to talk about its shipbuilding problems. The U.S. is quietly having to ask much smaller allies like Japan and Korea, who have retained their shipbuilding abilities, to help out. But due to their small size, they can only make a limited difference.

Meanwhile, similar problems exist with missiles, artillery shells, and basically everything else a military needs. And that’s not even getting into the issue of how many parts and components of what we do build are sourced from China (it’s a lot).

This has to change, and fast. By “fast” I mean “within the next three years”, not “within the next decade”. So how do we change it?

First, we have to ensure consistent funding for defense. Currently, funding that gets allocated to the military can’t actually be spent until it’s appropriated. Which means that each year, there’s a big Congressional fight over whether we’re going to actually spend the money we said we’re going to spend. Defense appropriations often get used as a political bargaining chip in budget battles by (sometimes) Democrats and (especially) Republicans. As a result, defense contractors can’t count on getting their money, which adds major risk and holds up production. This needs to end; Congress needs to change the defense spending process so that funding can be reliably disbursed year after year without the need for regular, repeated discretionary Congressional action.

Second, and on a related note, we need to implement multiyear procurement for defense contractors. Right now, we need a whole lot more businesses — both startups and existing businesses to commit to defense manufacturing for the next few years. But if we only pay them year by year, the risk of making that commitment is too high. So we need to commit to multiple years of payment, in advance.

Third, we need to remove barriers to factory construction. Environmental review (NEPA and similar state laws like CEQA) should be scaled back significantly for defense manufacturing, and other burdensome regulations should be relaxed for defense manufacturing specifically.

These should not be the only steps we take. There are a bunch of other ideas out there, such as investing in vocational education for defense manufacturing, leveraging public-private partnerships, using the Defense Production Act to relive various bottlenecks, and so on. I don’t have either the expertise or the time to evaluate each of these right now, though I plan to look at a bunch of them in depth in the future. But the key message is that we’ll probably need to do a bunch of different things, all at the same time, in order to even partially restore the Arsenal of Democracy by the later part of this decade.

In addition to reviving defense manufacturing, the U.S. needs to revive civilian manufacturing in areas that can be repurposed for defense in the event of a war with China. For example, civilian commercial shipbuilding is entirely different from naval shipbuilding, and the U.S. does very little of that; we should try to encourage the development of a domestic shipbuilding industry, preferably with regulatory reform instead of throwing money at it (since that money could be better used for naval shipbuilding).

We need to make sure not to outsource production of “foundational” or “trailing-edge” chips to China; these are older chips not covered by export controls, which China can already easily produce in large volume, which are used a lot by the military.

And we need a commercial drone industry. Currently, China is the world leader in commercial drones, while the U.S. has basically zero presence. We need industrial policy here; there needs to be an Inflation Reduction Act for drones, and we need regulatory changes, like designating areas where users can operate commercial drones beyond visual range.

This is not a complete list of things the U.S. needs to do in order to become the Arsenal of Democracy again, but it should be enough to give the general idea.

2. Make Europe understand that they have to take the lead on Ukraine

The aid to Ukraine in the recent U.S. national security bill was very good. It’ll stabilize the battlefield situation, which has turned into a grinding war of position. And it demonstrates America’s ongoing commitment to the transatlantic alliance.

But it’s not a permanent solution. More than half of House Republicans — 112 to 101 — voted against the Ukraine aid portion of the bill. Despite Trump himself softening on the bill, it’s clear that a large chunk of the GOP now views Ukraine as a culture-war issue, on which the true MAGA position is to oppose Ukraine aid. Some GOP legislators are warning that their compatriots are being swayed by Russian propaganda, and they are correct. What this means is that Ukraine can’t count on similar follow-ups to this aid bill in 2025 and beyond, no matter who wins the election — there’s always the possibility that the MAGA faction will be able to block it, just as it came very close to blocking it this time.

Second, and more importantly, the U.S. is facing a much bigger challenge: China. China’s manufacturing capabilities utterly dwarf Russia’s, and in fact are about as big as those of the U.S. and all of its allies combined. The U.S. has some allies in the Indo-Pacific — Japan, South Korea, Australia, and hopefully someday India — but these are not even close to being capable of taking on the Chinese juggernaut on their own. The U.S. needs to focus the vast majority of its resources in the Indo-Pacific if it wants to have any chance of deterring a major war. That will mean fewer resources for Ukraine.

Fortunately, Ukraine does have another major ally that is capable of checking Russia: Europe. I wrote about this last year:

Together, the non-U.S. countries of NATO have four times the population of Russia, and ten times its productive capacity. China is now feeding Russia arms and supplies, meaning that it’s effectively engaged in a proxy war against Europe. But even with Russia getting limited amounts of Chinese aid, Europe can outmatch the Russians if it gathers the political will to do so.

As it became clear that U.S. aid to Ukraine had become more reliable, some European leaders — especially French President Emmanuel Macron — started taking the lead, providing a bunch of ammunition, and talking tough about possible direct intervention in the war. But far more than extra shells and tough words will be needed. Ukraine needs massive amounts of air defense and drones to hold out against Russian assaults. If Europe can provide these things, Ukraine may be able to resist until the Russians give up and come to the bargaining table.

So the U.S. needs to make it clear to the Europeans that U.S. support will be patchy at best going forward. France, Germany, and the UK have to come together and commit the resources to support Ukraine for the long haul.

3. Add active liberal messaging to the information ecosystem

The TikTok divestment bill was an important milestone. Some still harbor free speech concerns, and no doubt TikTok’s lawyers will claim in court that a forced change of ownership is robbing them of their constitutional rights. But Zephyr Teachout argues convincingly that the ability to restrict foreign ownership of domestic mass media is among the most fundamental characteristics of a democracy:

Any effort to restrict a communication platform inevitably invites concerns about the First Amendment, but constitutional claims on behalf of foreign governments are extremely weak. In 2011, for example, a federal court rejected a challenge to the federal laws prohibiting foreign nationals from making campaign contributions. Then-Judge Brett Kavanaugh wrote that the country has a compelling interest in limiting the participation of foreign citizens in such activities, “thereby preventing foreign influence over the U.S. political process.”…

Forcing a TikTok divestiture…would address one specific issue: control over a dominant communication platform by a hostile foreign superpower with a well-documented interest in influencing domestic politics in the U.S. and other countries…

The basic premise of democratic self-government is the idea that people collectively make the rules of their community and collectively direct their laws…Could American corporations or individuals wreak just as much havoc on public discourse as the Chinese government? Yes. But on some level, that is part of the democratic bargain. Members of this political community must have unique rights to shape the institutions that coerce and constrain their behavior—rights not afforded to people, corporations, or governments outside the community…We should…affirm the historic norm that countries have the right to protect their communications, politics, and private data from foreign governmental control.

But even if this logic holds up in court and the ban goes through, the defenders of liberal democracy are still at a disadvantage in the global war of ideas. Totalitarian powers like China and Russia have large, well-funded propaganda departments to tell their stories to the world; liberalism’s advocates, in contrast, are largely volunteers working in their spare time.

That’s why the U.S. government should step in, and — in partnership with private citizens where possible — make the case for liberalism to the American people and to the people of the world. In a post last year, I sketched out what this would look like:

My favorite historical example of this is “Don’t Be a Sucker”, a 1940s film created by the U.S. Department of War to denounce Nazi ideology and build support for the desegregation of the military:

This is propaganda, but it’s not the kind of propaganda that forces people to consume it. It’s simply a liberal government telling the story of what it means to be liberal.

Private citizens, of course, can and should help with this as well. Left-leaning outlets like the New York Times and MSNBC could try to push back on the anti-American narratives that have taken hold among extreme progressives and leftists, and help restore some Rooseveltian patriotism. On the conservative side, Elon Musk and Twitter X may at least temporarily be allied with the faction that opposes Ukraine aid and wants to appease China, but he might eventually come around. And the Murdochs and Fox News could do a lot more to convince the conservative world that America and our system of alliances are worth defending from the likes of Xi Jinping.

4. Solidify the alliance with India and make more effort to court Indonesia

The New Axis of China, Russia, and Iran is far too powerful for the U.S. to oppose alone; even China by itself would be too powerful for the U.S. to handle one-on-one. Thus, U.S. national security relies on having strong allies. Under Biden, we’ve done a decent job of reinvigorating our Cold War era alliances with developed democracies in Europe and Asia. But these are generally smallish, shrinking countries, often with severe economic problems of their own. We need a bigger gang if we’re going to counter China.

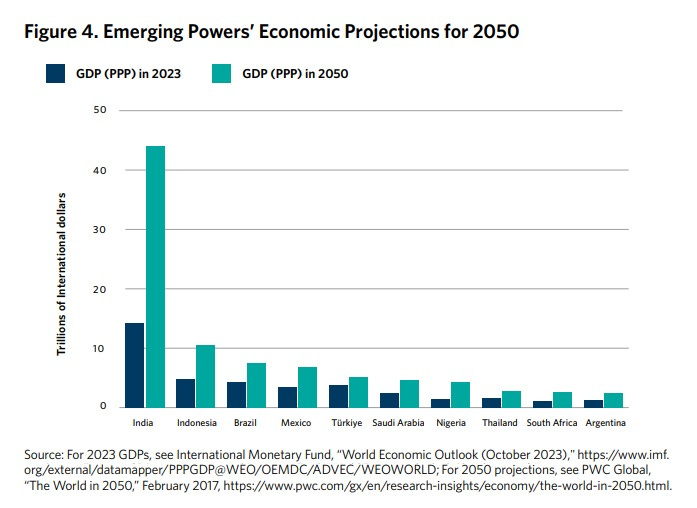

The most important future ally, of course, by leaps and bounds, is India. A recent Carnegie Endowment report emphasizes just how much India towers above other emerging powers, both in population and in projected economic heft:

Fortunately, India is also by far the most pro-American of the emerging powers:

In fact, as I wrote in a post last year, India and the U.S. are seeing a deepening engagement at both the highest levels of politics and the grassroots social and cultural level:

I don’t expect India to be willing or able to ride to Taiwan’s rescue in the event of a Chinese invasion later this decade. But as its economy, its military capabilities, and its friendship with other U.S. allies like Japan grow, India will become a more and more potent ally across a wide variety of fronts. So U.S. leaders have to continue to push very hard for deepening integration with India — investment, trade, diplomatic coordination, military exercises, multilateral alliances and regional pacts, and so on.

And we need to commit to continuing to take large numbers of Indian immigrants, to deepen the grassroots linkages between our societies (as well as getting America some needed talent). The first step here is to eliminate or at least weaken per-country gaps on green cards, a relic of the 1965 immigration system that discriminates against large countries.

India is the most important emerging U.S. ally, but there’s another very important “swing states” in the Indo-Pacific that we have not done enough to court: Indonesia.

Indonesia is a very populous nation with a lot of natural resources and latent manufacturing potential. It also has an incredibly crucial geographic location for any Asian conflict, since it controls the trade routes between China and the rest of the world. Yet the U.S. seems oddly committed to ignoring Indonesia, even as it drifts closer to the Chinese orbit. I complained about this in a post last year:

The problem has only gotten worse since then, with the election of a new President, Prabowo Subianto, who appears to be more pro-China than his predecessor. Meanwhile, China defeated Japan in a bidding match to build high-speed rail in Indonesia, and — unlike most of China’s Belt and Road projects — it appears to be a success.

Indonesia still cooperates militarily with the U.S., and worries about China’s claims on some of its waters. But the U.S. and its Asian allies need to step up their efforts to court Indonesia economically, offering infrastructure investment and development (perhaps with American financing and Japanese construction), FDI in Indonesian manufacturing and other industries, and trade opportunities. The U.S. can no longer afford to treat this vitally important country as the “biggest invisible thing on Earth”.

5. Disengage from the Middle East as much as possible

The U.S. will be hard-pressed to counter both China and Russia at the same time, even with Europe’s help. It will be impossible to do these things while simultaneously checking Iran in the Middle East and supporting Israel’s war in Gaza.

Campaigning against the Houthi pirates depletes America’s stock of hard-to-replace missiles and has accomplished little so far. Aid to Israel crowds out other budget items, and is not really necessary for Israel’s defense. And helping Israel prosecute its fairly brutal campaign in Gaza weakens America’s moral standing in the world, especially in the eyes of majority-Muslim Asian countries like Indonesia and Malaysia.

In a post last year, I argued that as horrible as Hamas’ October 7th attack on Israel was, the U.S. should nevertheless resist getting embroiled in the region, and focus its attention on Asia instead:

My assessment has not changed since then. Asia is a place where the U.S. is both badly needed, and in a position to do a lot of good, by helping democratic nations remain independent of an expansionist superpower. The Middle East is an increasingly irrelevant quagmire — a violent region with little to offer and little hope of resolution.

The days when the U.S. was powerful enough to defend the entire world at once are long gone. Now we have a choice of whether to stretch ourselves to the breaking point in the hopes that we can somehow bluff our way through all the conflicts at once, or to refocus our hard power on the points of maximum leverage in the defense of global liberal democracy. That doesn’t seem like a difficult choice.

So those are the five things I think the U.S. needs to do in order to bolster both its own security and the security of its allies, in the wake of the recent breakthrough on national security legislation. They are all difficult tasks that will require both sustained political will and delicate, skilled management. But I believe they are all within the realm of the possible.

As someone from the tech world who had never been involved with defense before, I've recently been helping out on a defense startup. As an element of what you said on "Rebuild the U.S. defense-industrial base": Having software backing every process has made a lot of American companies efficient and strong. It seems the DoD spends a relatively tiny, tiny percentage of their budget on software relative to private-sector companies and, where it does, doesn't have the procurement procedures in place to do it as well as companies to.

Software eating everything is one of America's greatest strengths and the DoD should take advantage of this strength too (with appropriate cybersecurity measures... which I admit is very hard.)

We will need to do quite a bit more to restore the Arsenal of Democracy. I refer you to the outline set forth in "American's Advanced Manufacturing Problem - and How to Fix It," by David Adler and William B. Bonvillian, American Affairs, Fall 2023, Vol. VIII, No. 3, pp. 3-30. Also, the tax and financial incentives that influence how executives decide upon making capital investments must be drastically changed.