Indiamerica

A new quasi-alliance is born, but there are still some challenges to overcome.

Incredibly, Antony Blinken’s trip to Beijing was the second most important event in U.S. geopolitics this week. The most important was Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Washington D.C., where he met with President Biden and gave a speech to Congress. You can watch the two leaders’ joint press conference here:

Or read a transcript of Modi’s speech here.

This wasn’t just a courtesy call. The visit included a startlingly broad array of economic and military agreements:

General Electric Co. plans to jointly manufacture F414 engines with state-owned Indian firm Hindustan Aeronautics Ltd. for the Tejas light-combat aircraft…

Biden and Modi also announced new defense collaborations, including progress on an order for MQ-9B SeaGuardian drones made by General Atomics, and an agreement that will allow American Navy ships to undertake major repairs at Indian shipyards…

“We are doubling down on our cooperation to secure our semiconductors, our semiconductor supply chains, advancing open RAN telecommunications networks, and growing our major defense partnership with more joint exercises, more cooperation between our defense industries, and more consultation and coordination across all domains,” Biden told reporters…

Applied Materials Inc. will announce a new semiconductor center for commercialization and innovation. Chip manufacturer Lam Research is announcing a training program in India for up to 60,000 engineers…

Indian companies also plan more than $2 billion in projects in the United States, including a solar manufacturing facility in Colorado, steel plant in Ohio, and optic fiber facility in South Carolina…

The announcements…also include…efforts by the US to make visas easier for Indian workers to obtain.

The U.S. and India are also discussing strengthening ties between their militaries, including in logistics and intelligence-sharing, Pentagon officials said. U.S. ships could call more frequently at Indian ports, and the two militaries could hold more joint exercises, for example.

Modi also met U.S. business leaders like Elon Musk, who expressed interest in making big investments in India.

So basically, what we’re seeing here is:

U.S. investment in Indian manufacturing

Indian investment in U.S. manufacturing

Sales of high-tech military equipment to India

Greater military-to-military cooperation

Space program cooperation

Easier immigration from India to the U.S.

These new agreements come on top of a vast array of other agreements and linkages that have grown up between the two nations in recent years. Tanvi Madan, a Brookings Institution fellow who studies the U.S.-India relationship, has a Twitter thread with a great rundown. Key points of cooperation include the Quad (with Japan and Australia), various other multilateral organizations, various defense agreements mostly aimed at countering China, sales of military hardware, joint military exercises, increased trade and investment, and so on. I was especially struck by this graph of how trade in physical goods has skyrocketed since Covid, making the U.S. India’s largest trade partner:

Madan also mentions the large and fast-growing Indian diaspora in the U.S., which now numbers over 4 million strong. That diaspora has rapidly become the highest-earning and most-educated ethnic group in the U.S., ahead of even Jewish and Chinese Americans. Indians and Indian Americans have become extremely prominent in business, technology, science, law, and medicine, and are making big inroads in politics and entertainment as well. America’s ever-present need for talent provides a powerful incentive for the U.S. to open up to Indian immigration, which in turn helps cement the broad-based bond between the two peoples. So I’m glad to see expanded visa programs among the things Biden and Modi discussed.

Should we call this increasingly deep and comprehensive partnership an “alliance”? International relations scholar Paul Poast makes a convincing case that the Russia-China partnership should be called an “alliance” even in the absence of a traditional mutual defense agreement, and one might be able to make a similar case for India and the U.S. If it was just a matter of military cooperation and policy toward China, I would make that case. But there are a couple of complicating factors here — India is still on fairly good terms with Russia, and the U.S. is still trying to be friendly with India’s old enemy Pakistan. So the two countries aren’t in complete alignment yet.

But it’s obviously headed in that direction. Biden called the partnership “one of the defining relationships of the 21st century”, while Modi declared that “even the sky is not the limit.”

The U.S.-India partnership seems like it’s about two things: economics, and China. Those are not independent; in the scramble to “de-risk” by moving manufacturing out of China, many companies are naturally looking toward India, with its equally vast labor force, as the natural alternative. On top of that, U.S. leaders realize that a richer India will be better able to balance China in Asia. But even if China weren’t a factor, the U.S. and India would still salivate over access to each other’s huge and lucrative markets.

The defense piece, of course, is all about China, and no one should pretend otherwise. China, not Pakistan, is India’s chief rival and biggest threat — it defeated India in a war in 1962, it still claims pieces of Indian territory, its soldiers make incursions into Indian territory that sometimes turn bloody, and it has attempted to encircle India with bases and alliances. With Russia now looking a lot weaker, the U.S. is realistically the only country that can help India to resist domination by its giant neighbor. As for the U.S., though nobody expects India to jump in to help in a war over Taiwan or the South China Sea, Americans realize that a stronger India means one less country China can push around, and one more rival that China has to think about.

In other words, even if we’re not quite there yet, there are many deep structural forces pushing India and America toward a true alliance. I believe it will come. But there are still some major challenges to overcome before everyone accepts the idea. On the U.S. side, some progressives are very upset about the prospect of an alliance with a country run by Narendra Modi, while on the Indian side, the shadow of U.S. support for Pakistan during the Cold War looms large.

Fear of Modi and the shadow of Cold War 1

Modi was welcomed with great enthusiasm by both Democratic and Republican leaders in D.C. But one small group of progressive legislators boycotted Modi’s speech, denouncing the Indian Prime Minister’s record on human rights. Those worries were echoed by progressives in the U.S. media, some of whom see Modi as an anti-Muslim bigot who’s destroying India’s democracy.

In general, as I wrote in my last big post about India, I think Americans are really bad at understanding Indian politics. This is partly because Americans are an insular and complacent people who are generally bad at understanding any other country’s politics, and partly because most Americans only recently started paying attention to India at all. Thus, educated American progressives tend to get their information about Modi from the most natural source — educated Indian progressives. And educated Indian progressives, generally speaking, despise Narendra Modi.

I think we have to be very careful with this sort of thing. For years, I watched progressive American expats and social media shouters denounce the late Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzo in the most extreme and apocalyptic of terms, calling him a fascist and declaring that his administration represented Japan’s return to fascism. In fact, this was total B.S.; Abe brought about an unprecedented opening up of Japanese society while staunchly defending democratic values. That experience has made me wary of buying into progressive denunciations of foreign leaders without first checking the evidence.

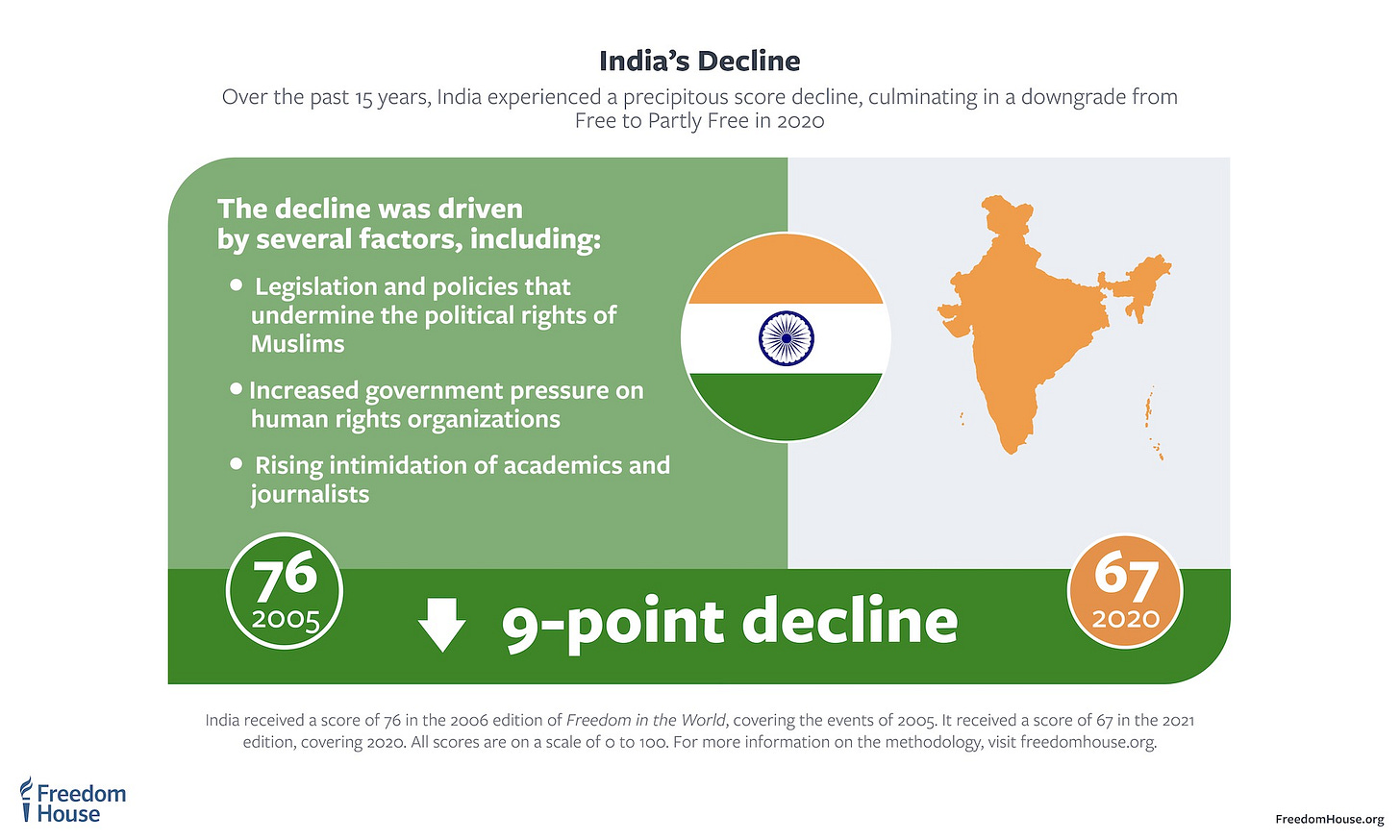

But that being said, the evidence absolutely does point to some troubling developments in Modi’s India. Freedom House, an organization that I generally trust (or at least, which I trust to be consistent in its application of its own standards), has downgraded India from “Free” to “Partly Free” under Modi. That is a big deal.

There are three main Modi actions that have people concerned, and in my estimation all of them are worth worrying about.

First and most importantly, there’s the problem of religion and citizenship. India is still a poor country with poor record-keeping, so many people don’t have documentation to be able to prove their citizenship. The Indian government has long been planning to change this by creating a National Register of Citizens. But the way they’re doing that could end up leaving a bunch of people stateless, some of whom came to India as refugees or unauthorized immigrants.

The obvious solution would be just to grant residents citizenship en masse, and then start enforcing borders only once the registry is complete. And in 2019, Modi’s government created a Citizenship Amendment Act that offered citizenship to refugees, but only for certain religions. Notably absent from the list of “persecuted religions” who get citizenship: Muslims. So the CAA, when combined with the NRC, leaves open the possibility that a bunch of Muslims could be mass-deported. Already some refugees are getting the boot. And even if the worst fears don’t materialize, there’s still the symbolism of sending a message to Muslims — 14% of the population — that they don’t really belong in India.

Other problems identified by Freedom House include the intimidation or suppression of the press, academia, and human rights organizations. The 2023 country report gives some details. Freedom House’s analysis is backed up by similar organizations like V-Dem, whose 2023 report called India “one of the worst autocratisers in the last 10 years”, the Economist Democracy Index, which said in 2022 that “the organs of India’s democracy are decaying”, and Reporters Without Borders, which says that “media freedom is under threat” in India. (Update: For those who want more qualitative argumentation than indices like the aforementioned provide, here is a collection of essays on the topic at the Journal of Democracy.)

So yes, I’m certainly concerned about the direction India’s governance is taking under Modi, despite his reassurances. But does this mean I think the U.S. should avoid an alliance with India? Absolutely not.

The U.S. is now in a great-power competition with China, and great-power competitions force bitter compromises and strange bedfellows. Remember that in World War 2, the U.S. allied with Joseph Stalin — the world’s second most brutal dictator, who turned his own country into a totalitarian nightmare and slaughtered 20 million of his own people, not to mention allying with Hitler to take over Poland before ultimately being betrayed.

The reason we allied with Stalin, and the reason this was the right thing to do, was because Hitler was even worse. We chose the lesser of two evils, and it was the right choice.

Again, during the first Cold War, we made alliances of necessity. Our quasi-alliance with China against the USSR put us on the same side as Mao, a madman who started a bunch of wars and who caused a famine that killed upwards of 30 million Chinese people. (In fact, this was our second alliance with Mao; the first was during WW2 against Japan.)

In other words, great-power competition forces us to choose the lesser of evils, and we’ve partnered with leaders who are infinitely worse than Modi.

And when weighing Modi’s actions against those of Xi Jinping and the CCP today, there’s really no comparison. Freedom House rates India as “partly free”, but China as one of the least free countries on Earth. Modi has degraded civil society and the free press; the CCP crushes these things utterly, and is building a techno-totalitarian surveillance state in their place. Modi might eventually deport a bunch of people; Xi already threw a million Muslims into concentration camps. India has refrained from a strong condemnation of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine; Xi seemed to give Putin the go-ahead. It’s Xi, not Modi, who threatens to plunge the world into a new era of war.

Also, it’s worth remembering that from India’s point of view, it’s the United States that’s the lesser evil. During Cold War 1, the U.S. aligned (mistakenly, in my view) with Pakistan. In 1971, Pakistan committed a genocide in Bangladesh, slaughtering up to 3 million Bangladeshis and raping hundreds of thousands until India invaded and put a stop to it. The U.S. knew about the killings but refused to condemn them, instead shipping weapons to Pakistan.

That dark and terrible history lingers on the minds of many Indians (Americans, by and large, don’t even know it happened). More recently, the U.S. invaded Iraq and elected Donald Trump, which doesn’t speak particularly well of our steadfast commitment to peace and liberalism.

So India is taking a leap and making a big compromise by allying with us, too, and we should remember that.

It’s also important to remember, I think, that even the most liberal and democratic countries can go through periods of illiberalism. In the early 20th century, the U.S. maintained the Jim Crow system and other forms of racial segregation and official discrimination. Woodrow Wilson censored the free press during WW1. FDR mass-deported a million Mexican Americans — citizens of the U.S.! — during the Great Depression. And so on.

Luckily, we got better. And so did lots of other countries — South Korea, Taiwan, Mexico, and so on. It made sense to believe in those countries during their darker days; I think we should believe in India now. It has very strong and deep traditions of democracy and pluralism. It has gone through authoritarian periods before, and come out of them.

And if the U.S. is going to help India get back to full liberalism, we’re not going to do it by publicly denouncing or shaming the country. And we certainly won’t do it by shunning India or trying to exclude it from multilateral organizations. That arrogant, high-horse approach wasn’t even particularly effective in the 90s, when U.S. power reigned supreme and U.S. moral authority was much stronger than it is today. It is worse than ineffectual now.

It will be easier for us to persuade India’s leaders to be more liberal if we do it politely, behind closed doors, as a friend and ally. (And frankly, India might persuade us to be a better country in certain ways as well.) Luckily, this appears to be exactly the approach Biden and the U.S. leadership are taking. Biden has good instincts for this sort of thing.

In any case, I am more inclined to celebrate the flowering of the U.S.-India partnership than to fear it. If there are any two countries that together can set the world back on a democratizing trend, while also continuing the story of global economic development and poverty eradication, it’s these two. Best of luck to Indiamerica.

Noah, thanks for the balanced approach.

I will take all these indexes with a large grain of salt. India has 20 political parties running various states and the central govt. How is that a lack of democracy?

India has 100 live news challenges and has the largest English Daily newspaper. Which other country can say that?

The citizenship act you mentioned is for persecuted minority religions from Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Burma etc. All of the minorities are Hindus and skihs etc.

Please check the atrocities against Hindus and others in Pakistan etc.

The whole point is to support these non-muslim religions who live Muslim dominated or Buddhist dominated countries.

The western media and progressives lack any real understanding of India.

"And in 2019, Modi’s government created a Citizenship Amendment Act that offered citizenship to refugees, but only for certain religions."

The CAA *didn't* do that. It provided an accelerated pathway to citizenship for certain persecuted groups in India's neighbourhood. Also singling out India is a bit rich given that American refugee policy has worked exactly that way (see: https://www.jta.org/archive/jewish-refugees-immigrants-benefit-from-clinton-budget-plan-2 ) and it currently has country of birth quotas that act as an exclusion act for Indian citizens from becoming permanent residents.

"Already some refugees are getting the boot."

You are confusing NRA stuff with the Rohingya situation. India is not a signatory to the UN HCR treaty and you are perhaps underestimating challenges in dealing with delicate balance of groups and ethnicities in India's northeast.

"Freedom House’s analysis is backed up by similar organizations like V-Dem, whose 2023 report called India “one of the worst autocratisers in the last 10 years”

Again, these rankings are heavily influenced with the very progressive ousted Indian elites and their methodologies have serious issues when it comes to India where they have been gamed. Prof. Babones of Uni. Syndey for instance has an excellent series of deep dives on these of See: https://newsletter.salvatorebabones.com/p/inside-the-v-dem-rankings