The U.S. economy shrugged off the tech bust

Maybe "sectoral recessions" aren't as dangerous as people thought.

In this week’s roundup, one of the items is about how some people think the U.S. is in a recession, when we’re actually in a boom. As for the proof that we’re in a boom, I’ll just quote myself a bit:

The U.S. economy is doing GREAT right now. Real U.S. GDP growth came in at a 4.9% annual rate in the third quarter, which is as fast as China’s official growth rate, and is unusually fast for the U.S. The unemployment rate continues to hover near record lows at 3.8%, while the prime-age employment rate is near record highs at almost 81%. Inflation has come way down and is now around 3.7%, with core inflation a bit lower, and median wage growth is outpacing inflation. Meanwhile, new survey data shows that Americans have gotten wealthier, and wealth inequality has narrowed.

But I noticed an interesting tweet while I was writing that section:

That’s not happening either, of course; most American industries are doing just fine. But it’s easy to guess why Jason thinks there’s a “rolling recession” — much of the tech industry, especially the venture-funded startup industry, has taken a beating since the end of 2021. It’s easy and natural to extrapolate the performance of our own little corner of the economy to the whole thing.

But in fact, it’s worth asking why the tech bust didn’t drag the U.S. economy into a general recession. In fact, there are plenty of macroeconomic models of how shocks in individual industries or even individual companies propagate throughout the economy and send the whole thing over a cliff. Horvath (2000) and Acemoglu et al. (2012) are two examples. The basic idea is not too hard to grasp — industries and companies trade with each other, so when one goes down, it buys fewer intermediate goods from the others, and so on.

Now, the caveat here is that there are macro models for basically any idea you can possibly come up with, and they’re all very hard to test empirically — for example, you can find evidence that sectoral shocks are very important, and evidence that they’re not important at all, and which result you decide to believe basically depends on which set of assumptions you like better. But it’s pretty widely accepted that the Great Recession of 2008 was prompted by the implosion of the finance industry, and most people think the bursting of the dotcom bubble had something to do with the mild recession of 2001. So it’s worth asking why the tech bust of 2022-23 didn’t have similarly negative results.

Anyway, first let’s review some of the details of how that bust happened.

How the tech bust of 2022-23 went down

The excitement around generative AI has been so intense that it’s hard for people outside the tech industry to even realize that much of the software industry is still reeling from a major shakeout. But people in the industry know. AI is great, but consumer internet, SaaS, fintech, crypto, etc. all took a beating.

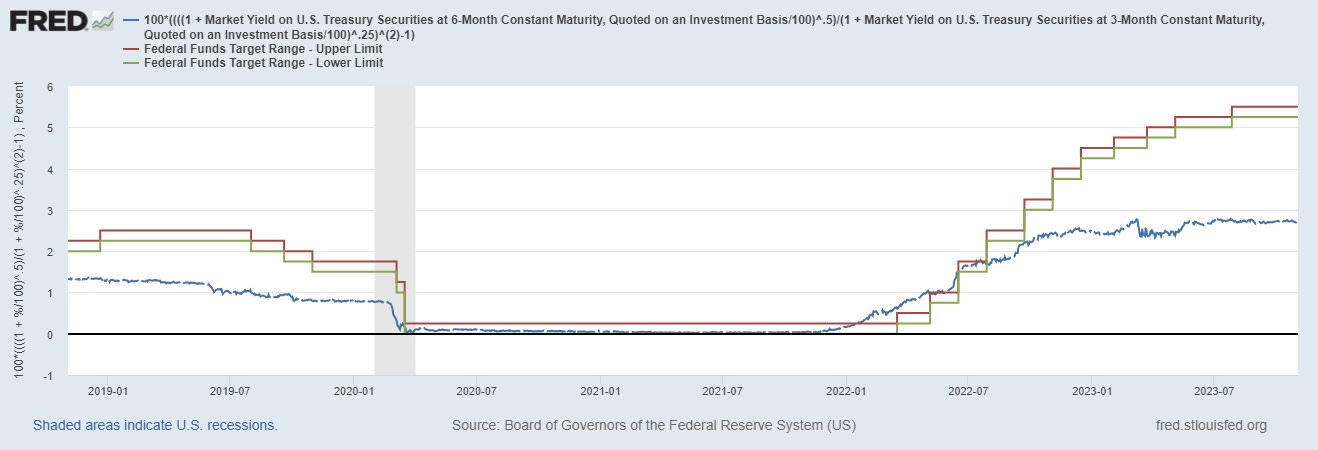

The whole thing started in November 2021, when two things happened. First, investors realized that interest rates were going to go up by a lot. In general, rate hikes are bad for stock prices, because they make it harder for companies to borrow money, and because they increase the “discount rate” that investors use to value future cash flows. If you start to expect interest rates to be higher, you should generally expect stock prices to be lower than they otherwise would have been. And when we look at the data on forward interest rates (which are closely related to interest rate expectations), we see that they started to rise in November 2021, a few months before the Fed actually started hiking.

A second thing that happened right around the end of 2021 was that earnings plateaued. Of course, investors didn’t know that yet, but maybe they suspected.

So these two things sparked a big collapse in tech stocks that lasted through the end of 2022. Here’s the NASDAQ:

If you look at the big tech companies — Apple, Microsoft, Google/Alphabet, Amazon, and Facebook/Meta — they end up doing about the same as the NASDAQ. Amazon did a bit worse because the end of the pandemic meant reduced importance for e-commerce, Apple and Microsoft did a bit better, but basically they all slumped in 2022 and rebounded somewhat in 2023. But lots of medium-big tech stocks got absolutely destroyed in the crash. Here are Shopify and Block, for example:

The carnage was widespread enough that it’s hard to pin on bad management. Stripe, which most people agree is among the best-managed of the medium-big tech companies, cut its valuation almost in half.

There were probably a number of reasons for this that went beyond low rates. The end of the pandemic meant a shakeout in e-commerce world and other stuff that people mostly consumed when they were shut in at home. Also, I suspect a lot of these companies seem to have been priced to win most of their respective markets, and those markets turned out not to be quite as winner-take-all as investors thought. On top of all that, I think there was a general realization that we’ve mostly finished building out the internet.

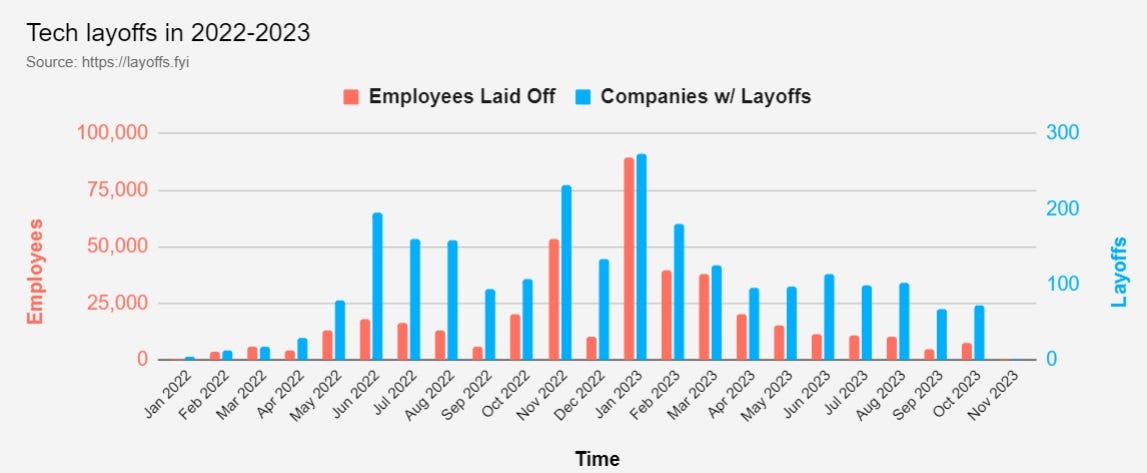

Slowing earnings, falling stock prices, and the prospect of rate hikes sparked a wave of layoffs by big tech companies, which crested in early 2023:

The carnage in medium-big tech companies also changed the game for the startup world as well. Startups are valued based on scenarios of how valuable they might become, and those scenarios depend on comparisons with successful companies. If you have a fintech company that people think has a 10% chance of being the next Block and a 90% chance of going bust, then its price — assuming no risk aversion on the part of the marginal investor — should be 10% of whatever Block’s price is, discounted by the time the company will take to get to that level of success. If Block’s stock price goes down by 80%, so should the valuation of the company. And when startup valuations go down, that means a lot of startups just won’t be able to raise money anymore.

A lot of startups weren’t immediately affected by this, since they had already raised a lot of cash, and could just live off that “runway” for a while. But with opportunities for follow-on financing having dried up, and many software business models having been shown to be disappointments, it was only a matter of time before those startups vanished. As of late 2023, that wave looks not to have crested yet. Here’s some data from Carta’s Peter Walker:

About half of the startups that closed shop did so without raising any VC rounds. The other half had at least one priced round in their history.

Within the cohort that had raised from VCs, 90% of the shutdown were either Seed or Series A startups.

34 startups that raised a Series B or later have shut down so far this year - that's higher than the 25 in 2022.

87 startups that raised at least $10 million have shut down this year. That's nearly 2x the total from last year.

Any way you slice it, this is the most difficult year for startups in at least a decade.

And here is his chart:

(This delayed reaction might be why Jason Calacanis thinks there’s a “rolling recession” going on; it might be rolling between different parts of his portfolio.)

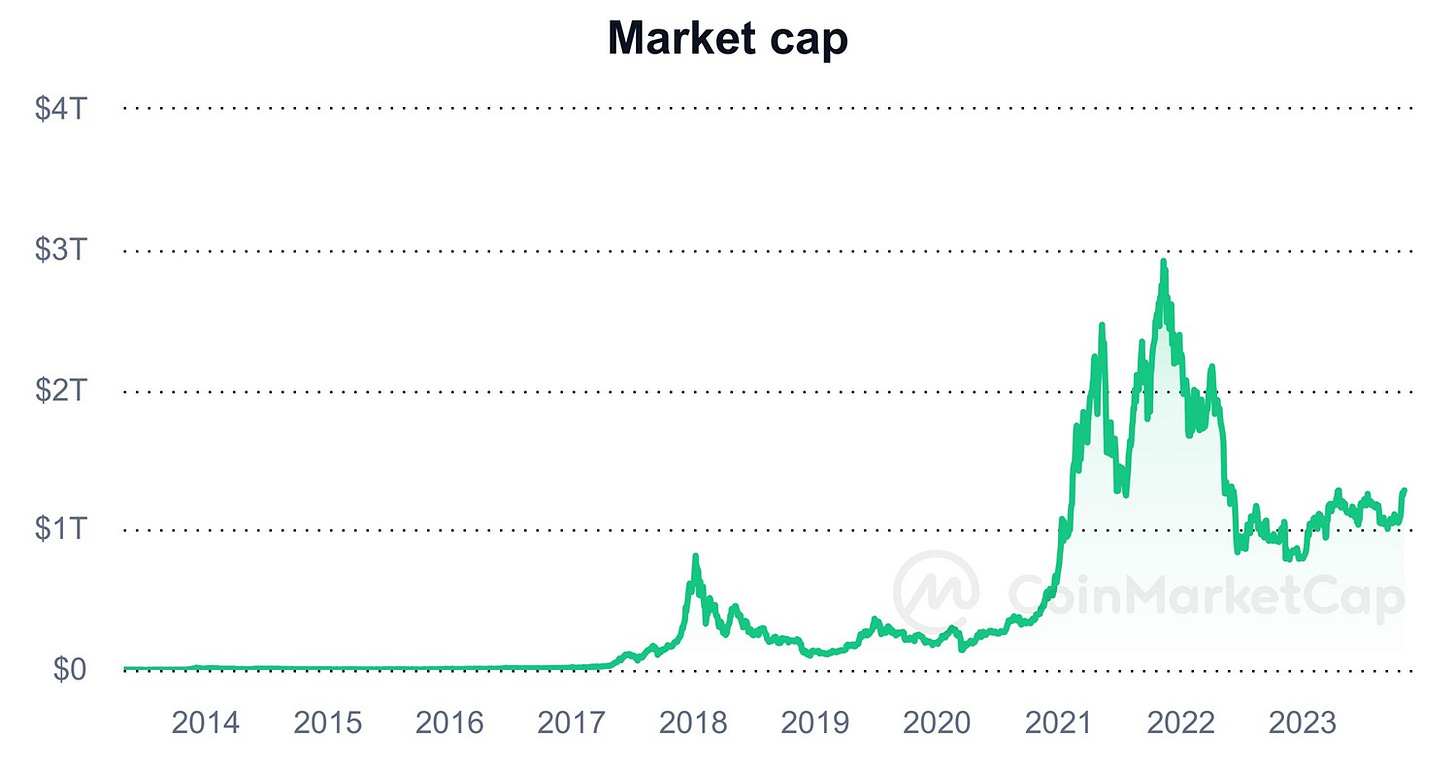

Meanwhile, all this time, another type of tech bust was happening: the crypto crash. High rates also hit crypto prices, and there was probably a good old-fashioned bubble in the asset class. That sparked a wave of collapses of prominent coins and exchanges, such as FTX and Terra/Luna, and reduced the demand for Bitcoin and Ether. A lot of prominent “web3” startups — Axie Infinity, OpenSea, Helium — also got ethered (pun intended) as well. All told, crypto lost more than half of its total value in 2022:

The crypto collapse hit the wealth of people in the tech industry very hard, since tech people had tended to be early crypto adopters, and thus had ridden the bubble on the way up. It also caused a lot of pain for VC funds that had gone all-in on web3. And it contributed to the collapse of a couple of medium-sized banks that had heavily served the crypto sector — Silvergate and Signature.

Speaking of banking crises, the final piece of the tech bust was the collapse of regional mid-sized banks that served a lot of tech industry people and companies in California. Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic collapsed in part because higher interest rates made them take big losses on their portfolios of long-term Treasury bonds. But the fact that a lot of the startups that had been their biggest clients had gotten vaporized, or could be expected to get vaporized soon, or were forced to cut back on their spending, was also a factor.

So over the course of the last two years, we’ve seen a crash in tech stocks, a crash in startups, a crypto crash, and major tech-related bank failures. And yet this has basically happened without causing any visible pain at all to the broader economy, as some people had expected it to. It’s as if tech doesn’t even matter to the rest of the U.S. business world. Why?

Why didn’t the tech carnage spread?

There are a number of reasons the U.S. economy might have shrugged off the tech bust like Superman shrugging off bullets. First, there’s the most obvious possibility, which is that the models that say one industry should be able to drag down the whole economy are simply misspecified or miscalibrated (that’s econ-ese for “wrong”). Maybe the linkages between industries just don’t matter that much, so that sectoral shocks just don’t spread.

Finance might be a special case here, because the financial sector is crucial for lending to all the other industries. So the moral of the story might be that as long as finance doesn’t go bust, we can weather carnage in any other specific sector.

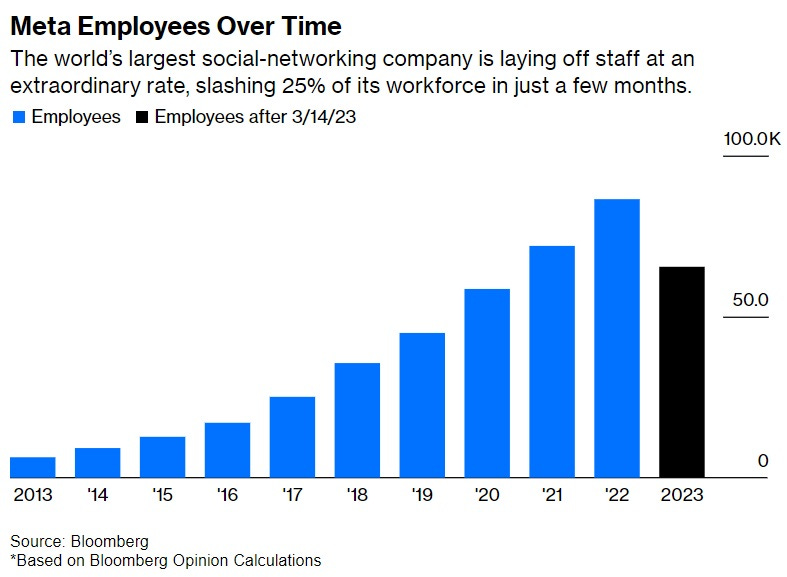

A second possibility is that despite the pain inflicted upon the portfolios of some tech investors, the tech crash just wasn’t that severe in economic terms. Earnings per share plateaued but didn’t really fall. Layoffs seemed brutal to people in the tech industry, because they had become used to ever-increasing headcount, but in numerical terms they mostly just canceled out the pandemic employment boom. Meta, which conducted some of the most severe layoffs, had a headcount as of March of this year that was actually higher than in 2020:

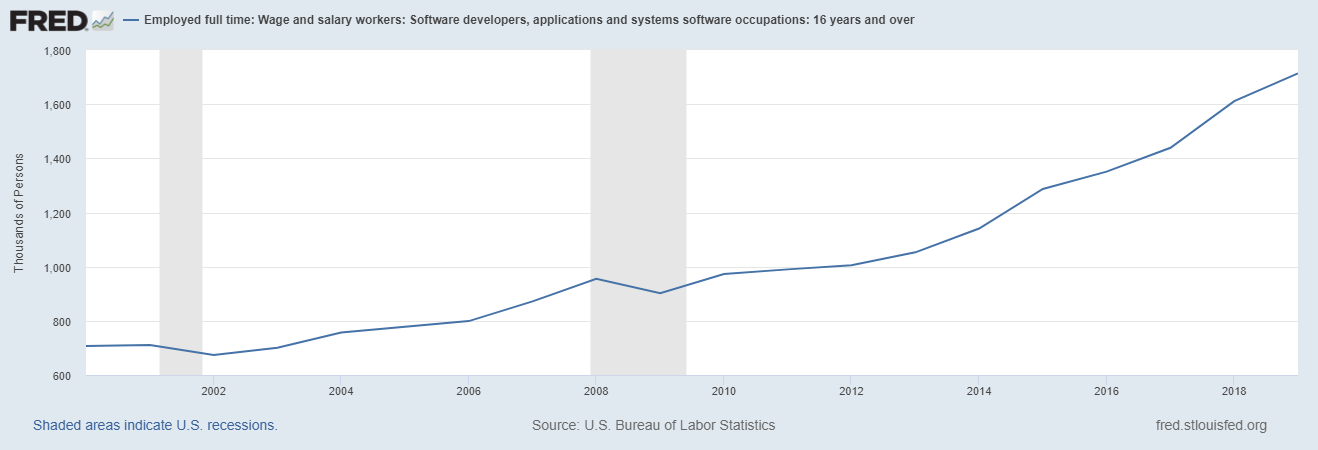

And remember that even as these layoffs have been happening, hiring for software engineers has been going on elsewhere in the economy. Official government statistics show that the number of software development jobs in the U.S. never even stopped growing:

Those jobs might not pay as well as Google or Facebook, but that by itself is unlikely to cause a bust.

And in terms of actual economic output, the government numbers say that real software output actually grew in 2022, while real investment in software products took only a minor and temporary hit:

And capex by the big software companies hasn’t fallen that much either. Here’s Amazon, which was the hardest-hit of the big tech companies:

In other words, though the tech bust moderated expectations for future growth in Big Tech and in the startup sector — and thus hurt stock values and made employees more pessimistic — it didn’t really hurt actual output that much.

Of course, the generative AI boom might have something to do with this. As the ever-excellent Ben Thompson writes, the big tech companies are well-positioned to benefit from the advent of LLMs, and they’re racing to spend in order to make sure they don’t lose the market. The startup sector has also received a boost from the wave of generative AI startups; it’s unclear how this investment will pan out, but it’s keeping capital flowing and providing some jobs. The tech bust might have been severe enough to impact the national economy if ChatGPT hadn’t suddenly ridden to the rescue. (Financial disclosure: I have invested in two AI startups.)

A final possibility, though, is that tech just isn’t that important to the rest of the economy in the first place. Remember that most of the macro models of sectoral recessions depend on network effects — if one industry goes bust, it buys fewer intermediate goods and services from other industries, and those other industries go bust too. But if software is a relatively self-contained production network, those linkages will be weaker.

Remember that the reason VCs love to invest in software is that it has such low costs. A manufacturing company has to order a ton of parts and materials and rent warehouses; software runs lean, with just some engineers and cloud computing and a little office space. And a lot of what software companies do buy is…software from other software companies. The same low costs for intermediate goods and services that allow software to (sometimes) generate such spectacular financial returns may also weaken the industry’s connections to the rest of the economy. What happens in Silicon Valley might simply stay in Silicon Valley.

In other words, software might act as sort of an “equity tranche” for the U.S. economy — a high-risk, high-reward sort of icing on the cake. When it does well, it creates a ton of value, and when it does badly, it doesn’t crash the rest of the economy — or at least, it doesn’t crash it too badly. That’s a mark in software’s favor, if you ask me — the more we rely on industries that don’t do what finance did in 2008, the better. But it also means that software industry people may look a bit silly when they over-extrapolate from their own corner of the world.

This economy is great for everyone other than speculators (stock traders, real estate developers, VC/PE, banks, etc.) that require asset prices to be constantly going up. Having to invest in projects that can deliver a guaranteed delta over investing in US Treasuries is more difficult so they have to make better decisions on handing out capital. A lot of people were making big payouts on all the stupid shit that was done in the last 20 years or so, at the expense of normal people. Now, good companies are making profits and thriving. Bad companies that had been propped up for no good reason are going away. It's the way it should be. Good companies paying good wages, employing people in useful capacities rather than chasing pipe dreams. Hope we don't mess it up. I'm not going to feel bad for all the speculators that have to go back to working real jobs now. There are plenty of good jobs available for them.

What is the effect of the $2t deficit? The number is clearly in excess of what we have come to expect from our government.

Perhaps all of that spending swamped the negative effects of the Tech sector contraction. Perhaps the future effects of all of that spending are an explanation for why some people are uneasy about the economy.