The student debt revolt failed, but Millennials will be fine

My generation will bear some minor economic scars into our prosperous middle age.

“I get to live the rest of my life like a schnook.” — Henry Hill

Back in the 2010s, I was in favor of student debt cancellation. There were a few reasons for this. First of all, inflation was low, so why not do a bit more fiscal stimulus, to get the economy all the way out of the hole it fell into in 2008? Second of all, economic dynamism was way down; freeing talented people of the need to make monthly loan payments might free them to start more companies and switch jobs more. And a one-time debt cancellation seemed like it would balance the score for the older Millennial generation, whose careers were scarred by graduating into the Great Recession.

Even though I was in favor, though, the idea always felt a little weird, for a couple of reasons. First of all, student debt cancellation by itself seems a little arbitrary. What about people who took out loans to start businesses? Or who paid off their loans already? Economists might not care about fairness considerations like this, but some people do. Second, even with means-testing, student debt cancellation isn’t going to benefit any of the poor people who never went to college. Third, a single debt cancellation might lead to demands for it to become a regular thing; that would mean that “student loans” would become a giant permanent government subsidy to colleges, driving up tuition even more. And fourth, the obsessive focus on student debt by the Bernie movement seemed to feed the impression that it was a movement of downwardly mobile entitled White kids with too much education and excessively high expectations — an artifact of elite overproduction.

But, whatever. The counterarguments were either theory or vibes, while the benefits in the here and now seemed clear. So I supported a debt cancellation.

Fast forward to the post-pandemic 2020s, however, and the case looked much less clear to me. Inflation had risen to the highest level since the 70s, meaning that it was no longer time for stimulus. In an inflationary environment, budget constraints start to matter, and a massive $400 billion debt cancellation — which is basically a form of targeted tax cut — would crowd out other, much more important spending priorities like infrastructure, research, welfare, and defense. Second, the U.S. seemed to have recovered some of its economic dynamism during and after the pandemic, meaning that there was less urgency on that front. As a result, I became much more equivocal about Biden’s debt cancellation than I would have been had it been proposed in 2018.

In any case, now the argument is basically moot. Whatever the economic merits and demerits of the policy itself, the Supreme Court ruled Biden’s program unconstitutional this week, meaning that the student debt will remain unless it’s discharged by an act of Congress. Which it probably never will be. So that, I guess, is that.

In addition, student loan borrowers are going to have to start making their monthly payments again; the pandemic repayment pause was ended in the recent debt ceiling deal.

The Millennial generation probably will be the most affected by the failure of student debt relief and the resumption of payments. In most regards, Millennials were financially similar to previous generations at age 30, but their student loan payments were greater:

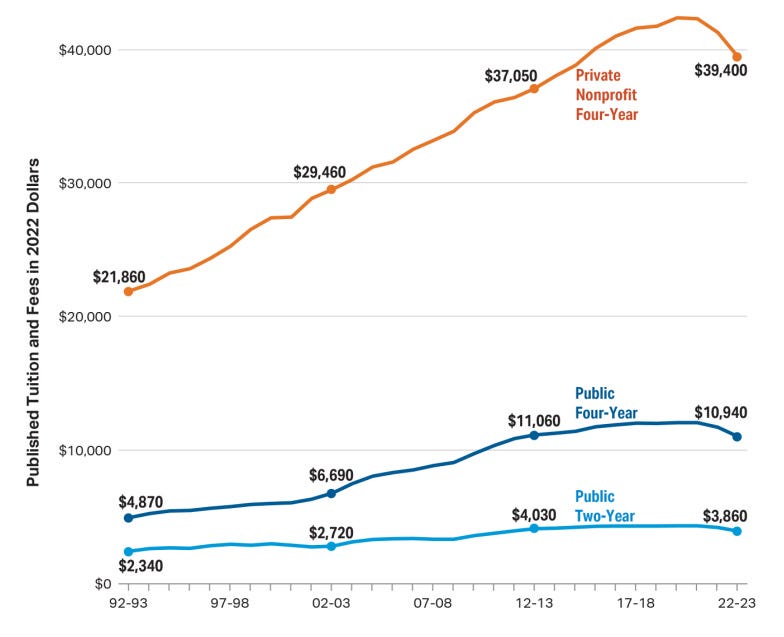

That student debt burden isn’t just a result of the Great Recession making loans harder to pay off. It’s really the product of an era of very high college tuition that might now be ending:

Some might call this a “bubble”, and in fact Millennials and their parents may have overestimated the value of a college degree and underestimated the danger of debt. But really I think this was just a rise and fall in demand. Millennials were an especially big generation, so demand for college spots was high even as our university system limited the number of spots at good schools. And Millennials went to college during the height of America’s shift to a knowledge-based economy, where a degree mattered more than ever before.

So really, the educated Millennials got doubly unlucky; they went to college at the height of cutthroat competition for spots, and then many of them graduated into the middle of a once-in-a-century recession. Millennials’ high student loan payments are basically a persistent scar from this bad luck. And the recent SCOTUS ruling and debt deal means that this scar will be more or less permanent.

Democrats aligned with the Bernie faction are, of course, extremely mad about the fact that defeat on the student loan issue was seemingly snatched from the jaws of victory. They are calling very stridently for Biden to do everything humanly possible to prevent student borrowers from having to pay their loans:

But it’s simply unlikely that anyone is listening. Biden tried his best to do student debt relief; now that that effort failed, it probably just doesn’t make much political sense to stretch the bounds of constitutionality and spend large amounts of political capital to prioritize the student debt issue, especially when the original plan received only mild enthusiasm for the general public. I still favor student debt forgiveness (though maybe when inflation is over), but now I doubt it’ll happen.

For all the young people who borrowed a bunch to get them through college and/or grad school, in other words, it’s back to the grind.

In fact, “back to the grind” seems like a good general descriptor for what’s happening to my generation right now. Many educated Millennials didn’t just want their student debt canceled; they also wanted to de-emphasize the “work” component of work-life balance. When the pandemic came along and prompted a shift to remote work, it seemed like exactly the lucky break Millennials had been waiting for; very large majorities opposed a full return to the office.

But a return to the office may be happening anyway. Work-from-home arrangements turned out to be more durable than some had expected, but there are signs they’re starting to drift back down:

Companies are pushing their employees increasingly hard to return to the office. And as the labor market weakens (which it’s sure to do at some point, since it can hardly get stronger than now), employers will have far more leverage to force employees to give up their days at home. Remote work will probably always be more prevalent before the pandemic, but perhaps only modestly so.

So there’s this narrative you can spin here about the Millennial generation. The narrative goes like this: Millennials were uniquely screwed by the Great Recession, and fought back against this unfairness by rejecting capitalism, embracing the Bernie Sanders movement, and dreaming of a world where they wouldn’t have to work nearly as hard. But eventually their revolution was politically defeated, and they all had to go back to work, with the ball and chain of their student loans forever shackled around their ankles.

That’s one way to look at it. Certainly I have friends who look at things this way, and during the late 2010s I definitely bought into this idea to some degree. But even putting aside the fact that this narrative only ever applied to the college educated, the years since the pandemic are suggesting a different story for the Millennial generation — one of prosperity and normalcy.

In a post a few months ago, I wrote about a ream of new data showing that in terms of income, wealth, and homeownership, Millennials are either keeping pace with previous generations or pulling ahead of them:

In the months since I wrote that, it has rapidly become conventional wisdom. Here’s some additional data from a May 30th article from Business Insider:

Despite these obstacles, the average millennial is faring better financially than they have in the past…[S]ome experts have argued that even compared to past generations, millennials are doing pretty well financially these days…

As of 2019, the median millennial household income, when adjusted for inflation, was roughly $10,000 higher than those of median Gen X and boomer households at the same age…

The average US millennial's net worth more than doubled between the first quarter of 2020 to $127,793 as of the first quarter of 2022, according to a MagnifyMoney analysis of Federal Reserve data…

Millennials crossed a notable threshold in 2022. By the end of the year, a majority of them — about 51.5% — owned a home, a RentCafe report…found…The millennial generation has been on a homebuying spree in recent years.

Those are objective criteria. But even in subjective terms, it turns out that Millennials are feeling pretty darn prosperous these days:

[C]ounter to the narrative that young people are struggling with money, feeling wealthy was most common among millennials and Gen Z, with 57% and 46% respectively reporting that they feel rich compared to just 41% of Gen X and 40% of baby boomers.

And on top of all the wealth they’ve already accumulated, and all the wealth they’ll manage to accumulate from their higher incomes and housing price appreciation, Millennials also stand to inherit the vast accumulated wealth of their parents’ — $78.3 trillion dollars in all. Over the next two decades, most of that will be transferred to Millennials. No, they don’t have this money in their bank accounts today, but the knowledge that it’s coming should help them feel much more secure about their own retirements. (Of course this is an average, and conceals plenty of inequality in terms of whose parents have money to leave them!)

Update: One additional point that I forgot to mention is that inflation is eroding student loans. If you compare total loan balances to nominal income (which rises in an inflationary environment), you see that student debt relative to people’s ability to pay off that debt has gone down a bit.

Of course that’s an average; not everyone’s income has gone up. But remember that this inflation has benefitted the wages of the people lower down in the income distribution more than those at the top. In any case, inflation has delivered a modest but real amount of debt relief — and not just for student debt, either, but for credit cards, fixed-rate mortgages, auto loans, and so on.

In other words, yes Millennials who have student debts will end up having to pay them, and yes, somewhere deep in the data their careers will always bear the scars of the Great Recession. But these will ultimately turn out to be minor burdens, not generation-defining ones.

In the end, my generation’s economic story will probably go something like this: We were raised in a time of great and unrealistic expectations. We got a couple of unlucky breaks, overpaying for college and enduring a big recession. But ultimately the vast engine of prosperity that is the American economy ended up lifting us up much as it lifted up our parents. We worked a little less, we started building wealth a little later, but eventually we got the houses and the yards and the two-car garages and all the rest. We flirted with socialism and rebellion, we complained about having to go into the office, but in the end we settled down and took our place in the great American middle class.

Honestly, there are worse fates.

This essay is full of sloppy generalizations and far below your best, Noah. It sounds like you’re addressing your friend group as your rhetorical “we,” not Millennials, writ large.

Because how could this “we” be the generation you’re ostensibly talking about and for? Most Millennials didn’t go to college at all, much less overpay for it. Only 38% has a four-year degree! This is part of the general tendency of the (highly-educated) media class to project their own experience too much.

Most Millennials didn’t flirt with Bernie or Socialism or whatever. Only a very modest majority of Millennials even voted in that election--still a much lower rate than for older generations. The boring truth is that most Millennials were like most Americans: relatively politically apathetic and disengaged from the process beyond (maybe) voting.

So what about all the other generalizations and revisionist counter-generalizations here? Are most Millennials living in a house with a two-car garage that they own? This is clearly incorrect since only barely over half of Millennials owns a house, and many of those houses, presumably, look a little different than the TV family homes you’re imagining. This also elides the fact that 49% of Millennials doesn’t own a home at all!

This isn’t a matter of nitpicking or nuance. You’ve totally obscured the reality for Millennials, not to mention the American population as a whole, adding to the general tendency of American media to assume that upper middle class Americans are normative, instead of a minority.

If student debt can’t be cancelled, how about improving it so that it’s terms are not so rigid and - I think - unfair to borrowers. Just make it more like conventional debt. When interest falls, let borrowers refinance. If borrower is overwhelmed, let chapter 11 address the challenge. Etc