The only thing worse than sweatshops is no sweatshops

Poor countries have to get rich somehow. This is the tried-and-true method.

I was going to write about U.S. politics today, but sweatshops came up in an online discussion, so I’ll write about that instead. It’s so rare to have interesting, substantive discussions about economic policy on social media, so I relish the chance to dive into one when it pops up.

It all started with an advertisement for American Eagle blue jeans. The ad makes a pun about the actress Sydney Sweeney having “good jeans”, and a contingent of progressives on social media decided that this meant that the ad was saying white people are genetically superior. Much ridiculousness ensued. The fashion blogger Derek Guy made a well-intentioned attempt to defuse the absurd fracas by diverting attention to the plight of poor working conditions in garment factories in developing countries:

On one hand, yes, I think it’s good to divert attention away from endless, pointless social media race wars, and toward real material conditions for the global poor. Whether garment workers in Bangladesh or Tanzania or Vietnam can put food on the table is far more important than whether some attention-seeking TikTokers call Sydney Sweeney a Nazi.

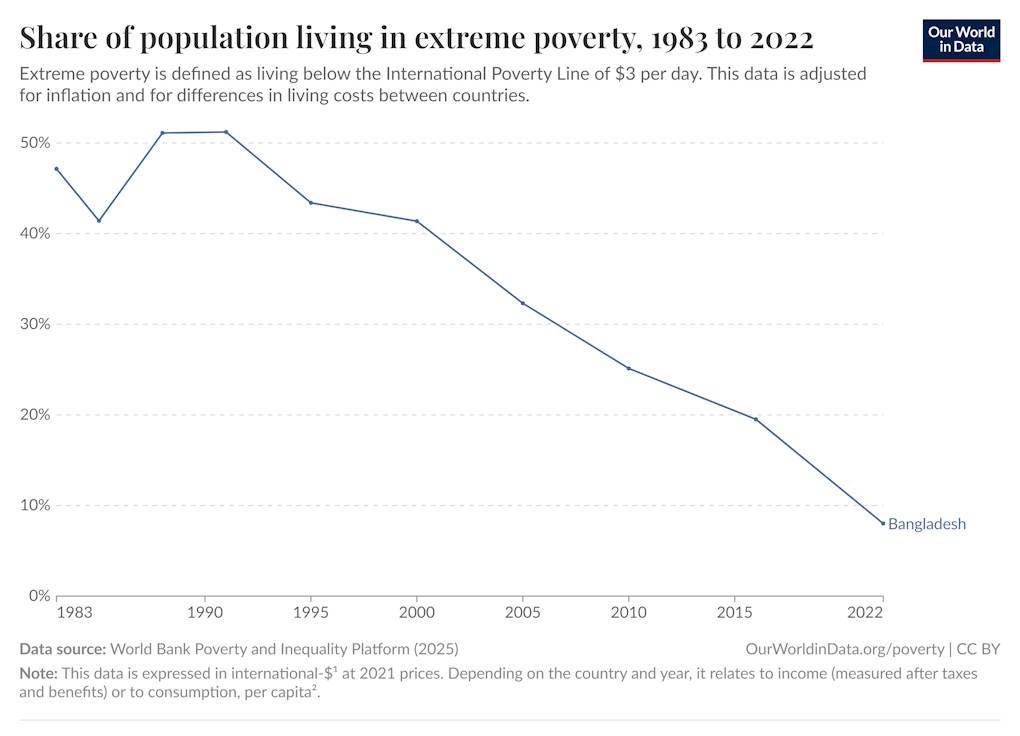

But at the same time, I think that while Derek is right about poor working conditions in many garment factories around the world, he completely ignored the benefits that those garment factories bring to poor countries — benefits that, in terms of human welfare, far exceed the slightly cheaper clothes that rich people get to enjoy. I posted a chart of extreme poverty in Bangladesh:

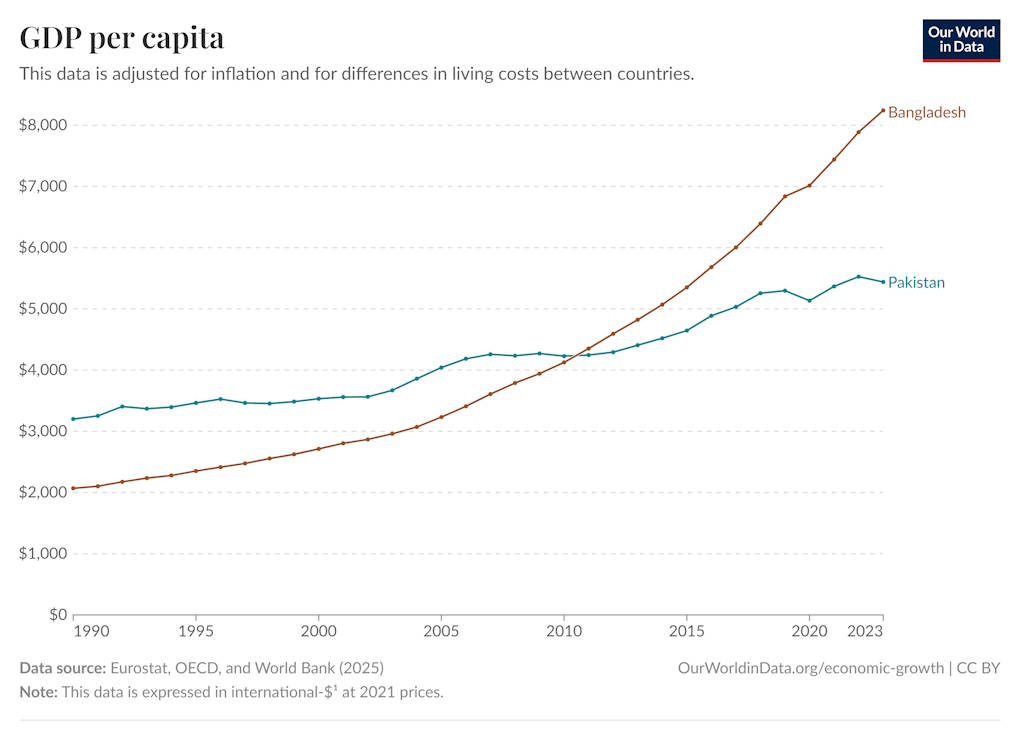

Bangladesh’s conquest of extreme poverty hasn’t come from any dramatic program of government redistribution, but from rapid economic growth. In the years since 1990, the country has more than quadrupled its living standards, blowing past Pakistan1:

Back in 2021, I wrote a post about how Bangladesh’s growth has been driven in part by the country’s huge investment in garment manufacturing:

Twenty years ago, most of your clothes probably had a label saying “Made in China”; today, there’s a good chance they say “Made in Bangladesh”. This is from a 2021 World Bank report by Gu, Nayyar, and Sharma:

At a time when many developing economies are experiencing premature deindustrialization, Bangladesh is being touted for an export-led manufacturing miracle. Bangladesh’s exports of ready-made garments (RMG), now second only to China, helped propel the country to lower middle-income status in 2015…Labor-intensive, export-oriented manufacturing driven by the RMG industry has been the cornerstone of Bangladesh’s recent economic growth…

What is more, the industry directly employs about 4 million workers and contributes indirectly to the creation of around 10 million jobs elsewhere in the economy. The RMG industry, which accounted for around one-third of total industrial production, has experienced an annual average growth rate of 10.5 percent over the past eight years…Low wages have helped Bangladeshi RMG exporters remain competitive since the inception of the industry.

The fact is, countries do not start out rich; they start out poor, and they get rich by figuring out how to make things that people want. In Bangladesh, and in some other developing countries, the most valuable thing they’ve figured out how to make (in terms of total value created) is clothing. Making that clothing involved putting people to work for low wages in factories with poor conditions — in other words, sweatshops. This was true for Britain and the U.S. in our early industrialization periods; Bangladesh is simply following in our footsteps here.

In my experience, “sweatshops are bad” is just one of those things that American progressives are supposed to believe — part of the canon, like the idea that incomes have stagnated since the 1970s or that defense spending is crowding out welfare spending. The idea is that greedy American capitalists hurt poor people in countries like Bangladesh by putting our factories there, just so we can have cheap shirts and blue jeans.

This idea is partly rooted in a very reasonable disgust at the sort of working-conditions that prevail in sweatshops. But it also comes from two very old leftist notions. The first is the idea that factory owners unfairly exploit workers, who — according to Marx — ought to capture all of the value of what they produce. The second is the idea that the developed world — especially America and Europe — got rich by stealing resources from poor countries. The idea of sweatshops as a curse upon the global poor comes from the combination of these ideas — instead of stealing aluminum or diamonds, we’re stealing poor Bangladeshis’ labor, paying them wages far lower than what they deserve, and forcing them to destroy their health with poor working conditions.

When I posted my chart of Bangladeshi poverty, Derek Guy responded with a lengthy defense of his initial indictment of sweatshops. Some excerpts:

First, many things contribute to the lowering of poverty. To get a sense of how low-end garment work contributes to this, we have to narrow in on this variable…Lucky for us, two people have. In 2017, [Chris Blattman] and [Stefan Dercon] published a study with the first randomized trial of industrial employment on workers. They worked with five Ethiopian firms — a shoe factory and a garment factory among them — to hire applicants at random and see how their lives may or may not improve.

Unsurprisingly, most workers quit within [a] month and returned to informal work or agricultural work. In those sectors, their pay was similarly low, but at least they didn't face the hazardous industrial work conditions. Crappy garment work, it turns out, was not better for them…

[A]ny time the subject of sweatshops come up, someone who considers themselves to be an economist brings up the economic benefits of paid employment, no matter how low…

But what are we arguing here? This woman committed suicide because she was forced to work dehumanizing 16-hour shifts. If she didn't produce enough that day, she would be fined, taking away money from the very little she was paid. Women in the factory say they are sexually abused — coerced into sex and asked to strip off their clothes for inspections. Their passports are held so they can't leave. These are often exploited migrant workers.

When Rana Plaza [in Bangladesh] collapsed, it's notable that none of the workers wanted the international companies to pull out. They want work! They simply just want work under better conditions. If we view labor as a global issue, shouldn't we — as workers ourselves — be in solidarity with workers abroad?…

[S]houldn't we push for better conditions? Why is it, when sweatshops are brought up, some wish to dismiss such concerns? Is it not possible for consumers to be smarter about their shopping, push for better conditions for workers abroad, and avoid cheap, trendy clothes that don't even make them happy in the long run, but require the immiseration of workers abroad?

But Derek badly misreads the 2018 study by Blattman and Dercon. He claims that the study examines the impact of sweatshops on poverty. But it does not. This is from the abstract:

Working with five Ethiopian firms, we randomized applicants to an industrial job offer, an "entrepreneurship" program of $300 plus business training, or control status. Industrial jobs offered more and steadier hours but low wages and risky conditions. The job offer doubled exposure to industrial work but, since most quit within months, had no impact on employment or income after a year. Applicants largely took industrial work to cope with adverse shocks. This exposure, meanwhile, significantly increased health problems.

Basically, this study took some people who were already applying to work in sweatshops, and gave them the jobs they wanted, and then most of the people didn’t like it and quit.

That is an interesting and important result! It means that in the short term, some people can be wrong about the kind of jobs they would actually want (which has implications for assumptions about rationality). It also means that at any given moment, sweatshops probably have greater labor supply than they would if people had good information about what working in a sweatshop is like.

But Blattman and Dercon’s study does not say that sweatshops don’t reduce poverty! First of all, it’s obvious that many sweatshop workers do not quit — or at least, not nearly as fast as the subjects of this experiment. If every sweatshop worker quit rapidly, sweatshops would quickly run through the entire available labor pool. Someone keeps working in those factories, so there must be some difference between the typical sweatshop worker and the marginal job applicant. The study doesn’t say anything about those existing workers.

Even more importantly, Blattman and Dercon’s study doesn’t say what would happen if all the sweatshops in Ethiopia closed up shop. If all the existing workers at the existing sweatshops suddenly found themselves out of work, they’d go do something else — agriculture, or local services, or whatever. That increase in labor supply in the other poor-person occupations would probably drive down wages in those occupations, leading to an increase in poverty.

And by this same token, Blattman and Dercon’s study doesn’t say what would happen if Ethiopia opened a lot more sweatshops. If government policy or foreign investment spurred the creation of a whole bunch of new garment factories in Ethiopia, it would increase labor demand. This would presumably raise both employment and wages in Ethiopian sweatshops, which would reduce poverty.

So Derek Guy simply misread the implications of the Blattman and Dercon study. In fact, Chris Blattman himself jumped in to clarify that he agrees with me about the overall impact of low-wage manufacturing industries on poverty:

I authored this study & I agree with [Noah] that the main thing driving most countries out of poverty is industrialization. In a weak economy, with few factories, and a few good non-farm options, industrial jobs are no more desirable than the other bad opportunities, but…a growing industrial sector, tends to compete for labor and overtime. Drive up wages and working conditions. It’s a bumpy imperfect process but outside of oil. I’m not sure any other country has reached middle or high income another way.

Fortunately, as I wrote in a follow-up tweet, we do have a lot of other research papers that do measure the impact of sweatshops on living standards. The tradeoff, unfortunately, is that because they tackle this bigger macro question, most of these papers are forced to use empirical methods that are much less solid and reliable than Blattman and Dercon’s.

Economic growth and poverty reduction are macroeconomic variables, as is nationwide investment into industries like garment manufacturing. The problem with macro variables, put plainly, is that there is a lot of stuff going on at once, and so it’s hard to tell what causes what. Basically, to get any sort of intelligible result, you have to make some pretty strong assumptions about the order in which things happen, or about which variables affect which other variables.

But when people try making the most reasonable assumptions they can, they keep coming up with the result that Bangladesh’s garment boom was a major cause of its spectacular economic growth since 1990. For example, here’s Islam (2019):

This study attempts to explore the [statistical relationship] among economic growth rate, ready-made garments (RMG) exports earning and foreign direct investment (FDI) inflow in Bangladesh. It uses time-series annual data for the period 1986–2018…The RMG exports earning significantly improves the economic growth rate both in the short run and long run. The more the RMG exports earning, the more will be the economic growth rate.

And here are Jiban and Biswas (2022), who use a different statistical approach:

Ready-made Garments (RMG) export earnings, which are almost 80% of the total exports of Bangladesh, have been recognized as one of the main catalysts for the recent development of the country. Therefore, the need to determine whether the RMG export had served as a mechanism for increasing the GDP growth as well as the economic development of the country is topical and pressing…Using data from 1990 to 2020 for Bangladesh, we have found long-run as well as short-run associations among RMG Export earnings, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), and GDP growth…Our result supports the proposition that RMG export earnings are one of the main growth engines in Bangladesh and this sector leads growth in other sectors also in the long term.

A similar paper by Paul (2014), who uses an approach similar to that of Islam (2019), finds the same result. And Tang et al. (2015), who look at four different countries, conclude that exports are important for growth in all four (though the relationship only holds true in some time periods and not in others).

So although we don’t really know for certain that sweatshop industries are a major force raising poor countries out of poverty, our best guess is that they are.

As for the more immediate impact of sweatshops on poverty, we have somewhat better evidence on that question. We can look at the effect of trade liberalization policies — which encourage the creation of export-oriented sweatshops — on regions that get more sweatshops, versus regions that get fewer. Vasishth (2024) does this, and finds positive effects on health for the children of women in areas with lots of sweatshops:

In this paper, I estimate the inter-generational health impact of maternal employment opportunities using evidence from the ready-made garment industry in Bangladesh. This industry was exposed to a trade liberalization policy in 2005, which generated spatial and temporal variation in the establishment of garment factories and therefore, potential employment opportunities for women. Using a difference-in-difference strategy, I find that the expansion of this sector improved the probability of neonatal survival for children who are born in areas that experience higher growth in employment opportunities post trade liberalization. This is driven by the improved labor market participation by mothers, enabling them to delay childbirth and improve their intra-household bargaining power. [emphasis mine]

Unlike Blattman and Dercon’s paper, Vasishth (2024) isn’t a randomized experiment. But it gets a much broader look at the effects of sweatshops on poverty, because it doesn’t just look at workers applying to work at sweatshops — it looks at everyone in the whole area where sweatshops are located. Remember that an important way that sweatshops raise wages is by increasing labor demand, forcing other employers to raise wages in order to retain their workers.

So while it’s not settled science, the evidence does clearly seem to indicate that sweatshops reduce poverty in poor countries — just as most economic theories would predict. If you’re deeply invested in the progressive narratives of capitalist exploitation of workers and rich-world exploitation of poor countries, it’s tempting to disregard, dismiss, or simply avoid reading this evidence. But we owe it to the world to do better than that. This isn’t one of those issues where we can afford to get it wrong, because if we let ourselves buy into narratives that encourage bad development policies — such as restricting imports from poor countries, refusing to buy clothes made in those countries — it will be the world’s most vulnerable who suffer.

But what about Derek Guy’s argument that we can push for better working conditions for sweatshop workers abroad? In fact, this is something that happens a lot. The U.S. has many mechanisms in place to demand and monitor better working conditions at factories that sell products here. And poor countries pretty much always start implementing minimum wages and stricter safety standards after they escape extreme poverty.

These policies often happen after big industrial disasters, like the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in the U.S. in 1911. After the Rana Plaza factory collapse in 2013, Bangladesh made a concerted effort to improve conditions in its garment industry. International retailers also put pressure on Bangladeshi factories to make life better for their workers. And lo and behold, it worked! Bossavie et al. (2023) find that these efforts did improve conditions and wages in the Bangladeshi garment industry:

After the tragic factory collapse of Rana Plaza in 2013, both the direct reforms and indirect responses of retailers have plausibly affected workers in the Ready Made Garment (RMG) sector in Bangladesh. These responses included a minimum wage increase, high profile but voluntary audits, and an increased reluctance to subcontract to smaller factories. This paper estimates the net impact of these responses…As intended by the reforms, we find that increased international scrutiny improved working conditions by 0.80 standard deviations…[W]e do not find that workers’ wages were negatively impacted: instead, the post-Rana Plaza responses increased wages by about 10%.

That’s a great outcome! But unfortunately, those improved conditions only apply to workers who still had jobs in the industry. It might be the case that well-intentioned activism to improve working conditions in poor countries slows down industrialization in ways that outweigh the direct benefits.

Grier et al. (2023) think this is the case. They find that the reforms after the Rana Plaza collapse led to investment flowing out of Bangladesh to places where labor was still cheaper, leading to a slowdown in the Bangladeshi garment industry:

This study investigates the impact of anti-sweatshop activism on garment industry employment and the number of firms in Bangladesh following the 2013 Rana Plaza factory disaster. The disaster led to activism that created two major brand-enforced factory fire and safety agreements. We…find that it led to 33.3 percent fewer garment factories in Bangladesh by 2016 and 28.3 percent fewer people employed in Bangladesh's garment industry by 2017. Given the importance of the garment industry in Bangladesh's development in providing a pathway out of extreme property, our finding raises important questions about the efficacy of anti-sweatshop activism.

But Harrison and Scorse (2006) paint a brighter picture. Looking at the effects of anti-sweatshop campaigns in Indonesia in the 1990s, they find that some factories move out, but surviving factories hire their workers instead — at better wages and in better conditions:

This paper analyzes the impact of two different types of interventions on labor market outcomes in Indonesian manufacturing: (1) direct US government pressure, which contributed to a doubling of the minimum wage and (2) anti sweatshop campaigns. The combined effects of the minimum wage legislation and the anti sweatshop campaigns led to a 50 percent increase in real wages and a 100 percent increase in nominal wages for unskilled workers at targeted plants. We then examine whether higher wages led firms to cut employment or relocate elsewhere. Although the higher minimum wage reduced employment for unskilled workers, anti-sweatshop activism targeted at textiles, apparel, and footwear plants did not. Plants targeted by activists were more likely to close, but those losses were offset by employment gains at surviving plants. The message is a mixed one: activism significantly improved wages for unskilled workers in sweatshop industries, but probably encouraged some plants to leave Indonesia.

Of course, the way countries can retain jobs and improve wages and working conditions is to raise productivity. In the rich world, we often sneer at the idea of just choosing to raise productivity, because if we could, we would already have done it. The same is not necessarily true in developing countries, which often still have low-hanging policy fruit they can pick.

One of these is technology adoption. Nayyar and Sharma’s 2022 World Bank report recommends this:

All in all, Bangladesh’s emphasis must shift to broader considerations of efficiency and quality as it seeks to diversify its export basket and move up the value chain…Our report finds that firms with higher technology levels in Bangladesh’s manufacturing sector perform better.

They recommend that the garment sector — and other sectors — promote rapid technological upgrading.

The really interesting question — which I don’t think we know the answer to yet — is whether or not anti-sweatshop campaigns from America or Europe force poor countries to invest more heavily in technology and education. Higher wages and more expensive safety measures force factory owners to raise productivity or die.2 That could nudge inefficient managers into investing in better machines, and it might nudge poor-country governments to provide their people with more and better education.

So while progressives like Derek Guy are way too dismissive of the economic benefits of sweatshops, their preferred solution to the problems — activism to force factories in poor countries to raise wages and improve working conditions — might be the right thing to do anyway. After all, Britain and the U.S. started out their industrialization by making a lot of cheap clothes with cheap labor, but they eventually moved on to higher-value, more capital-intensive stuff — and got far richer as a result, while also making working conditions much safer and more pleasant.

Bangladesh would do well to follow in those footsteps next, and if activism by rich-world progressives gives it the nudge it needs to take the next steps, then that’s all for the best. But if that activism simply causes garment factories to close en masse, robbing Bangladesh of its most important lifeline out of desperate poverty, well…that would be bad. So progressives in the rich world should be very careful here; it’s someone else’s lives and livelihoods that hang in the balance.

Pakistan, as it happens, has also made major progress in reducing extreme poverty, but more through redistribution rather than growth.

This isn’t nearly as far-fetched as it might sound. In fact, one of the most prominent theories of the Industrial Revolution is that expensive wages in the UK sparked a tech boom that eventually became self-sustaining.

Twenty years ago, my daughter had a social studies teacher who taught about the evils of sweatshops. It gave me an opportunity to have a conversation with my daughter about the alternative scenario where the workers didn't have that employment opportunity. That sometimes what we might consider to be unacceptable through our POV is a better alternative. This is a fair look at this issue and I appreciate the nuanced approach to nudging these countries toward better working conditions.

Great post. It’s disappointing that many subscribers are calling this post “ghoulish.” That reaction reflects a flawed mental model of how high-margin, high-wage industries actually emerge in a nation-state.

In their minds, these industries appear fully formed—without any understanding of how low-wage, low-margin sectors typically lay the groundwork. Over time, as physical and human capital accumulate and skilled labor pools deepen, these sectors move up the value chain into higher-value, higher-wage activities.

India’s IT and BPO industries began with low-margin call centers but gradually evolved into hubs for R&D and full product divisions (GCCs). Similarly, much of East Asia’s electronics manufacturing started with basic assembly before advancing into complex OEM production.

When developing countries legislate with this progressive mental model, the results are often disastrous. Labor protections that are sustainable in high-margin industries can render low-margin sectors unviable—effectively preventing poor countries from ever climbing the value chain in the first place.

The difference between a Bangladesh and a Mali is that Bangladesh at least attracts foreign investment, Mali has never netted fdi over a billion dollars since independence. The people there are either cotton & peanut subsistence farmers or they are artisinal miners for gold. There wont be any scaling up the value chain in Mali unless a multinational takes advantage of their cheap labor to make t-shirts like Bangaldesh did in the 2000s. Just like what China did in the 1980s or Taiwan did in the 1950s.