Car wars

A flood of cheap Chinese imports is upsetting the global industrial order.

A trade war is brewing between Europe and China. There are lots of reasons that relations between the two are deteriorating — Chinese support for Russian war production, European companies “de-risking” by moving investment out of China, Italy’s withdrawal from the Belt and Road project, and so on. But one sore point that has gotten a lot of attention is the auto industry.

Basically, China is flooding Europe with electric cars. Over the past two years, China has gone from an also-ran in the auto industry to the world’s biggest car exporter. EVs are a huge chunk of those exports, and most of China’s EV sales go to Europe:

Some forecasts say that by 2025, about 15% of EVs bought in Europe will be made in China — some by Western automakers like Tesla and Volkswagen, some by Chinese companies like BYD.

It’s very easy to understand why this is happening. China massively subsidizes the production of electric vehicles, and Europe massively subsidizes the consumption of electric vehicles. When that happens, any Econ 101 model can easily predict the outcome — China will produce a lot of EVs that are sold in Europe.

In fact, this basic dynamic was present even before the recent export surge. Usually, most cars are made close to where they’re sold. But even in 2021, Europe was buying more EVs than it was making:

But China’s EV export surge is more recent, so let’s go over some of the reasons it’s happening.

First, here’s a good Bloomberg article about the EV subsidy regime in China. China pays manufacturers a subsidy worth more than $1400 per EV they produce, provides EV companies with cheap land and financing, and heavily subsidizes R&D in the sector. Both China and Europe pay people to buy EVs, and their governments buy EVs directly. But China subsidizes local production a lot more than Europe.

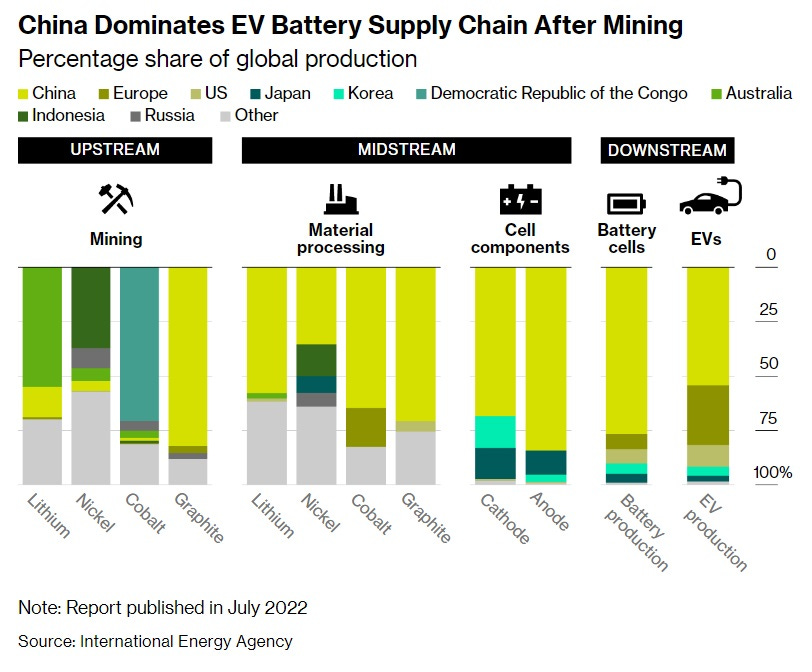

That’s one reason for China’s export dominance, but not the only one. Another is that China controls nearly the entire supply chain for EV batteries, except for the initial mining:

An electric vehicle is a much simpler machine than an internal combustion car — it’s basically just a battery with wheels. The battery in an EV represents about 40% of the car’s purchase price. Making EVs in large numbers is a lot easier when the supplier is right nextdoor; batteries are 33% more expensive in Europe than in China.

Batteries are also about a quarter of an EV’s weight. The fact that they’re all made in China cuts down on the amount of shipping cost you can save by locating car factories close to consumers.

Yet another reason is macroeconomic. As everyone knows, China is in the middle of a big economic slowdown, which has cut local demand for new EVs despite all the consumption subsidies. Europe’s economy is in the dumps as well, but China basically planned to produce enough EVs for a much faster-growing Chinese economy than the one they ended up with. So Chinese EV producers are stuck with massive inventory that they can’t sell domestically. So they’re slashing prices and dumping the inventory on Europe.

And finally, let’s not discount the ingenuity and innovation of Chinese auto and battery engineers and entrepreneurs. The industry shift toward EVs gave upstart carmakers a once-in-a-century opportunity to do an end run around the entrenched dominance of the old-line companies that knew internal combustion engineering backwards and forwards. European startups could have challenged Volkswagen and Renault and Mercedes-Benz. They did not. Instead it was Chinese companies like BYD and SAIC, along with one American company, Tesla, who seized the day.

So thanks to subsidies, supply chain advantages, a technological shift, and macroeconomics, Europe is getting a ton of cheap Chinese-made EVs dumped on their markets. And Europe’s leaders are mad about this, calling for investigations into Chinese EV subsidies. That could end in tariffs against Chinese-made cars. At a press conference after the recent China-EU summit, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said:

If you just look at the last two years, the trade deficit has doubled. This is a matter of great concern for a lot of Europeans…The root causes are well known, and we discussed them…Politically, European leaders will not be able to tolerate that our industrial base is undermined by unfair competition…[C]ompetition needs to be fair.

(I should mention that Europe isn’t the only one thinking along these lines. Turkey is also moving to block Chinese-made EVs from flooding the country, using non-tariff barriers.)

This reaction is hardly surprising, given the importance of the auto industry to the European economy. In a world where electronics manufacturing has clustered in Asia and software has clustered in the U.S., auto manufacturing was one major sector where Europe still stood relatively strong. It’s a mature industry, so Europe’s fetish for regulating new technologies was less likely to damage it. It’s a heavy industry, so the forces of agglomeration are less powerful than for electronics, where parts can be shipped cheaply; auto production tends to be distributed throughout the world, with most cars produced close to where they’re sold, which allowed Europe to make most of its own cars even as its economy lost competitiveness and dynamism overall. And Germany, in particular, has a thriving cluster of auto engineering talent that allows them to make really good cars (or at least, really good internal combustion cars).

Losing the car industry could thus push Europe further along the path to deindustrialization. Cheap Chinese EVs are a boon to European consumers, and they help speed the green transition and reduce carbon emissions. But the competition also threatens to put a bunch of European workers out of a job — 7% of the region’s workforce work in the automotive sector. Traditionally, Europe has been much more concerned than the U.S. about protecting its industries from foreign competition; the EV spat with China will be a test of whether this is still the case, or whether Europe has embraced more of a “neoliberal” approach to trade.

But there could also be a national security angle here too. The Ukraine war is stalemated, and promises to be a long slog, even as U.S. domestic politics puts American support for Ukraine in jeopardy. That means that the job of supporting Ukraine’s continued independence will fall to Europe; and if Ukraine does fall, Europe will still be on the hook, since Putin will then turn his eyes to Poland and the Baltics. So Europe will need to match Russian war production, in areas like shells, missiles, artillery, air defense, drones, and armored vehicles. A domestic auto industry gives Europe much more ability to repurpose production lines and ramp up defense production when needed. If the auto industry flees to China, Europe will be that much more vulnerable to Russia. In fact, this is one reason the auto industry is so globally distributed today; during and after World War 2, lots of countries decided they needed car industries in order to maintain strong militaries.

So if Europe does decide to protect its car industry, what might it do? Tariffs on Chinese-made cars are one option, of course, but they come with several obvious limitation. First of all, their impact will be limited by exchange rate adjustment; the yuan will simply depreciate against the euro to at least partially offset the tariffs. Also, tariffs don’t do much to help European carmakers become more competitive in the export markets they used to dominate. The fact is that Chinese-made EVs are mostly just better than European-made ones right now, and tariffs aren’t going to change that.

In order to address these issues, Europe would need more than tariffs. It would need an equivalent of the U.S.’ Inflation Reduction Act — a major program of production subsidies, not just for EVs themselves but for the batteries and the mineral processing facilities necessary to make them. Europe would also need to simplify and slash some of the overgrowth of regulation that it has piled up around the auto industry over the last few years. And it would need to subsidize R&D in the EV sector more heavily.

And another important step would be something Europe has shied away from doing in recent times: encouraging startups. It’s no coincidence that Tesla, a startup automaker, was able to run rings around the stodgy old giants of GM and Ford, with their deep reliance on legacy markets and legacy technology. Europe has no Tesla; if it really wants to compete with China, it needs at least one.

In other words, if Europe is going to save its car industry, it’s going to have to finally leave the comfortable stasis it has slipped into over the last few decades. That stasis, driven by regulation and complacency, was never really sustainable; as soon as old tentpole industries like auto manufacturing were hit by external shocks, the whole system was inevitably going to creak and crumble.

Europe lucked out for a long time — the internal combustion engine maintained its dominance, and Chinese demand hungrily hoovered up German-made cars. But the shock came, in the form of the shift to EVs, and now the long, easy daydream is over. Europe’s leaders can choose to meet the challenge, or they can hold more meetings and issue more empty rhetoric. Incidentally, that’s the same choice that’s facing them on a great many fronts right now.

There is absolutely no one better on the planet than Noah Smith at 'splaining economic issues. He is superbly well informed on economics, and his communication skills are exceptional.

But I frequently disagree with his geopolitical assessments. Even if the US stops supporting Ukraine, Russia cannot win and then attack Poland and the Baltics.

1. As military technology changes, the advantage shifts back and forth between offense and defense. Military analysts agree that the Ukraine war proves that without a robust Air Force, defense Is currently dominant. Neither Russia nor Ukraine has a robust Air Force, and neither has been able to budge the frontline significantly since November 2022. Thus, Ukraine can return to their tactics of 2014 - 2021, and simply hold Russia to the territory they already occupy with relative ease.

2. Because Russia cannot occupy the whole of Ukraine, there is no way they will ever attack Poland and the Baltics. This war has diminished Russia's military resources by at least half. Not even Putin is crazy enough to sign up to attack a NATO country. He would have to totally rebuild the Russian army before he even tried.

3. The following is a minor consideration, but Putin does pay attention to public sentiment in Russia. A telephone poll indicated that more than 50% of Russians would like the war to end right now. The war is so unpopular in Russia that Putin doesn't plan to mention it during his presidential campaign. Russian is currently obtaining most of its recruits from non-Russian populations. If the Russian people have no bodies of loved ones to bury, their only suffering is economic, and Putin can continue to pursue a policy that has basically become unpopular. As for the non-Russian populations, they are so fragmented, that they have little collective political power.

As you point out, on EVs, China has built real capability. Right now, ignoring Tesla, they are likely the best at building EVs...world class. There is also real innovation happening there in mass production of batteries which is why Ford wants to license from Chinese battery maker. The real question is: Will the CCP find a way to screw this up ? We will see, but my guess is yes. One need only look at Alibaba to see what can happen. The regression of the Xi regime vs the Deng regime is very sad.

At a higher level, one thing to keep in mind is that the dominant role of an automobile is declining. At a very fundamental level, conventional passenger cars are one of the worst utilized assets one can own. The average automobile is parked 95%+ of the time. Capitalism, especially driven by the explosion of on-demand services, is relentlessly optimizing this down with sophisticated alternatives which are lower cost and higher productivity. As this continues, the aggregate demand for traditional cars will go down .... based on utilization alone... this can go down by an order-of-magnitude (10X). Virtualization was the first big turn in this move (ecommerce, online education, telehealth, work-from-home, etc), Fleetization (uber, food delivery, other shared services model) is next, and the final turn will be autonomy (when the technology matures).

Fifty years from now the importance of traditional auto will be as muted in the overall economy as trains from the 19th century.