Skilled immigration is a national security priority

A joint blog post by Noah and Minn Kim on America's need for a national skilled immigration strategy.

This blog post is co-authored by Noah Smith and Minn Kim. Minn is the founder and CEO of Lighthouse, an immigration startup supporting the world's top technologists. She's also a former venture capitalist in AI, robotics working with technical talent globally.

Most discussions of immigration focus on the asylum seekers entering the U.S. illegally through the southwestern border. But there’s a second immigration issue that’s even more important, yet tends to fly under the radar. This is the issue of skilled immigration – the process by which the U.S. enlarges and replenishes its talent pool and sustains its lead in high-tech industries.

The U.S. has always relied on skilled immigration, from its very inception. Religious and political dissidents, and entrepreneurs seeking new opportunities, were key to America’s development in the 18th and 19th centuries. In the early 20th century the source shifted to South and East Europe, including Jews fleeing the Nazis. In the late 20th century, persecuted businesspeople and intellectuals fleeing communist regimes provided yet another wave of skilled newcomers. The biggest influx, however, came from the 1965 immigration reform that allocated around 15% of green cards based on employment.

The resulting wave of skilled immigrants – mostly from Asia, but also from various other regions of the globe – reinvigorated American science and technology. From Charles Kao, the “godfather of broadband” who laid the groundwork for modern internet infrastructure, to seminal researchers in artificial intelligence such as Raj Reddy and Fei Fei-Li, skilled immigrants have served as pioneers of nearly every high-tech industry.

In the 2020s, the issue of skilled immigration is more important than ever, for two main reasons. The first one is aging – the U.S. needs tax revenue to pay for an increasing number of retirees, and skilled immigrants earn a lot of money and thus pay a lot of taxes.

But an even more important reason is national security.

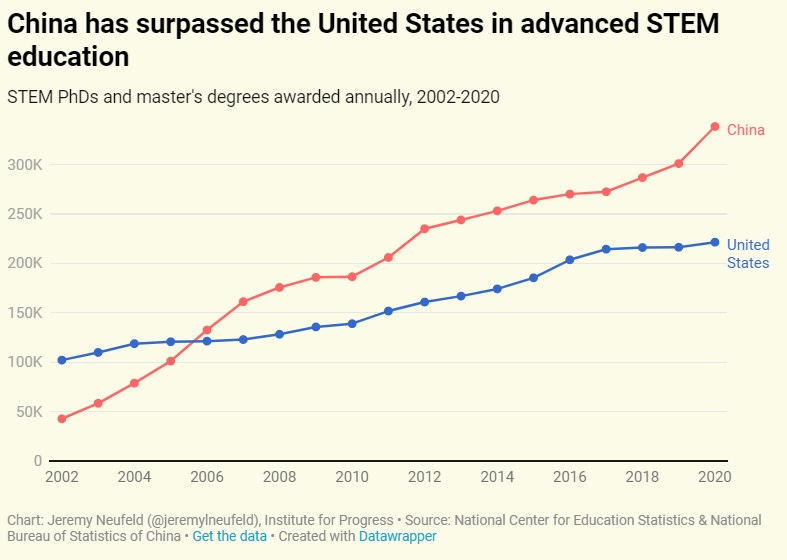

The U.S. is now locked in a long-term economic and geopolitical struggle with China, a rival four times its size with a well-educated workforce, top-ranked universities, and a growing lead in many scientific fields. China now has more highly-trained STEM workers than America, and the gap is only growing.

Maintaining a lead in industries like AI, semiconductors, and advanced manufacturing – all things that are essential for national defense as well as big contributors to national wealth – will require the U.S. to have more than its share of the world’s human capital.

This is why calls to “just train Americans” instead of recruiting skilled immigrants ring so hollow. Of course the U.S. needs to train its own skilled workers, and it should constantly be striving to improve its education system and to direct students toward the fields where they’re needed most. But at the end of the day the U.S. represents only 4.2% of the world’s population, while China represents 17.4%. China has a much bigger talent pool than America because it’s simply a much bigger country. If the U.S. wants to match China’s gigantic pool of human resources, it must supplement domestic talent by recruiting from abroad. Mathematically there’s simply no other option.

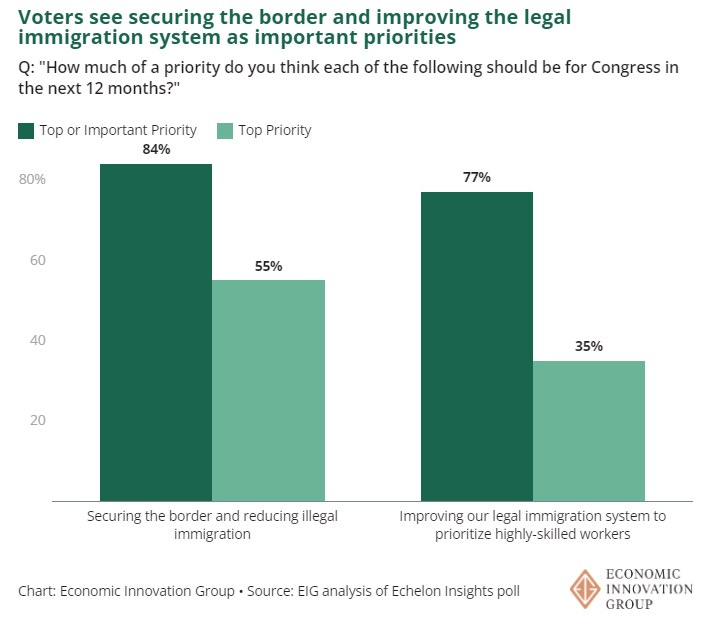

Fortunately, Americans are extremely supportive of skilled immigration. Despite the anger over the southern border, Americans from both parties want to recruit more skilled foreigners to work in their country:

In fact, support for border security and support for skilled immigration aren’t in conflict at all:

Even Donald Trump, for whom suspicion of immigration is a signature issue, recently declared on a podcast that he would give a green card to any foreigner who completed a college degree in the U.S. Trump’s campaign quickly walked back the remarks, but the idea was a good one, and it shows that Trump instinctively recognizes the importance of recruiting skilled global talent.

The U.S. media has seen many calls for more skilled immigration – including plenty on this blog. But the national security implications of the issue often go unstated. And there also needs to be more discussion of concrete ways to get more skilled immigrants to the U.S.

The U.S. semiconductor industry: A tale of two immigrants

If there’s one industry that everyone agrees is strategically important, it’s the semiconductor industry. Computer chips power precision weapons, sensors and battlefield surveillance, and basically everything else the military needs to do. That’s why the chip industry has been the focus of a bipartisan industrial policy push.

No two companies illustrate the U.S.’ strengths and weaknesses in semiconductors better than Nvidia and TSMC. The stories of these two companies show precisely why skilled immigration is so strategically important – but for very different reasons.

Nvidia is a U.S. company. It’s the world leader in the design of GPUs, the type of chips used in AI – and which Nvidia invented. The skyrocketing demand for Nvidia’s products recently made it the world’s most valuable company. Even if that lofty valuation doesn’t last, there’s no denying that Nvidia is a staggering success for American industry.

One of Nvidia’s founders, and its current CEO, is an immigrant. Jensen Huang was born in Taiwan, and moved to the U.S. to live with an uncle – also an immigrant – when he was nine. Huang worked at AMD and other chip companies, then co-founded Nvidia when he was 30. He has been its CEO since its founding, and has become one of America’s most iconic businessmen. These days he gives large amounts of money to U.S. educational institutions like Oregon State, Oneida Baptist Institute, and Stanford University.

With the decline of Intel, Nvidia is now America’s leading champion in the chip industry – a bastion of U.S. technological excellence that’s crucial for keeping America in the lead in the fast-moving and hugely promising AI industry. Without Nvidia, the U.S. would be in a much weaker geostrategic position relative to China.

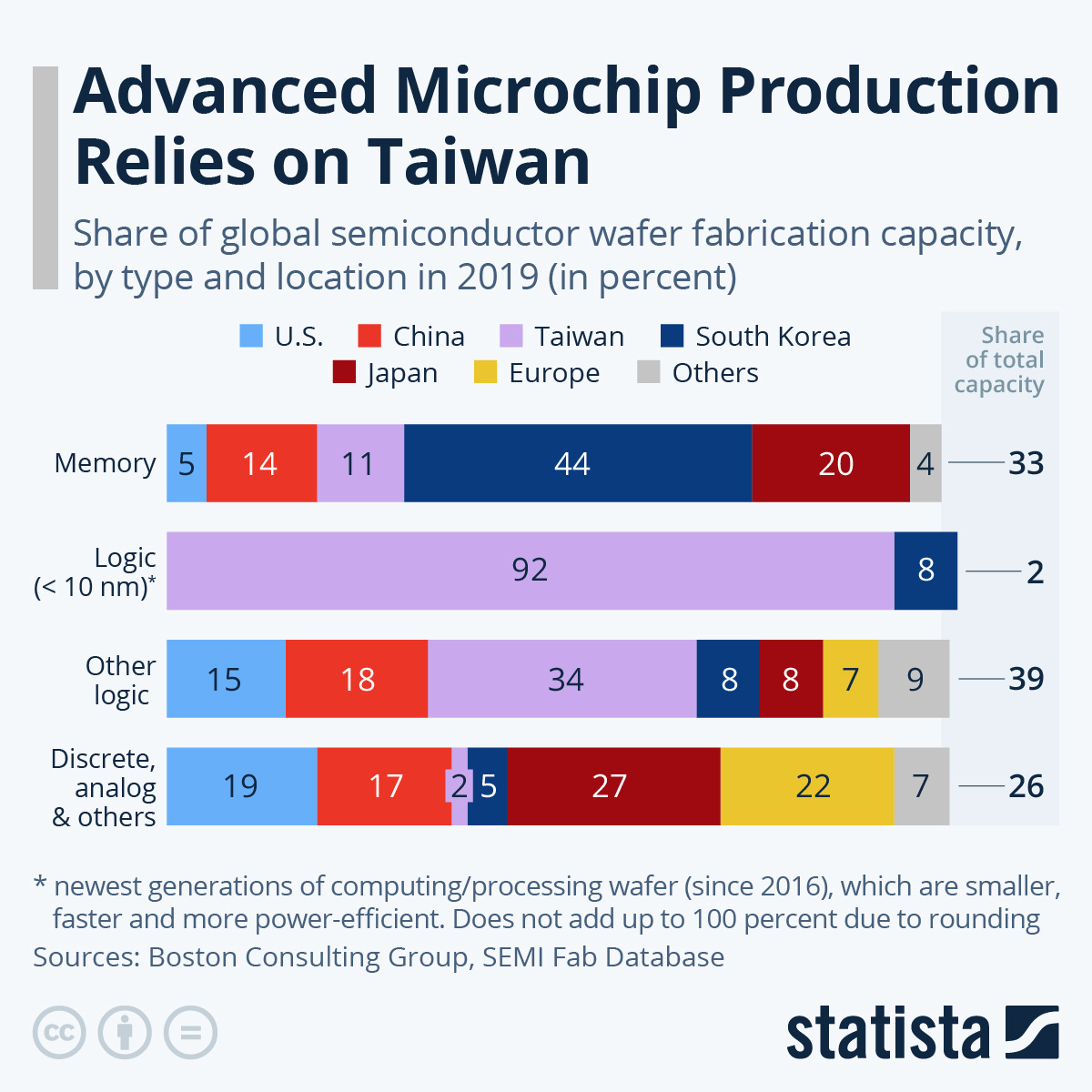

But despite still being the leader in chip design, the U.S. has lost its lead in the physical manufacturing of chips. The leading position is now occupied by Taiwan, which makes almost all of the world’s most advanced processors:

Taiwan’s dominance in chip fabrication is a big strategic headache for the U.S. (as Donald Trump has noted). Because Taiwan is claimed by the People’s Republic of China, it may soon be on the front lines of a war, putting not just U.S. chip supply but world supply in danger. But how did Taiwan, in Trump’s words, “take our business away”?

The answer is skilled immigration. Taiwan’s dominance in chip fabrication is overwhelmingly due to a single company, TSMC – now the world’s eighth-most-valuable company. All other Taiwanese chip manufacturers are basically negligible in comparison:

TSMC was built with significant help from the Taiwanese government, but it would not have succeeded if not for the efforts of its visionary founder, Morris Chang.

Chang wasn’t born in Taiwan; in fact, he was born in China. When he was 18 in 1949, he moved to the U.S. to go to Harvard and then to MIT. A few years later he got a job at Texas Instruments, one of America’s leading semiconductor companies at the time (it was the very early days of the semiconductor age). He stayed at TI for 25 years, improving their fabrication operations tremendously and eventually becoming a vice president. But after being passed over for promotion to the head of the company, and disagreeing with TI’s strategic direction, he left. He first went to another U.S. company, but was then recruited in 1986 by the Taiwanese government to start a company in Taiwan.

Chang was a genius in the field of semiconductor engineering. He realized that if a chip company focused on fabrication and left the design of chips to other companies, it could become highly specialized and outcompete companies like Intel that did both in-house. That bet paid off spectacularly.

It’s no exaggeration to say that Chang’s emigration from the U.S. to Taiwan is responsible for Taiwan’s dominance of chip manufacturing. Had he stayed in America and created his foundry there, the U.S. might still be in the lead.

Meanwhile, had Jensen Huang left America for Taiwan the way Morris Chang did, the U.S. might also have lost its lead in chip design. In fact, this wouldn’t have been hard for Jensen to do – he loves the country of his birth and constantly promotes it to the world. He’s a celebrity there, and he’s often seen at Taiwan’s famous night markets, munching away. And yet he started his company in the U.S., and never moved back to Taiwan.

It would be an exaggeration to say that the immigration choices of Jensen Huang and Morris Chang are the only reason that America is the leader in chip design and that Taiwan is the leader in chip fabrication. Industrial policy plays an important role, as well as differences in the education systems and talent pools of the two countries. But without a doubt, America’s loss of Chang and its retention of Huang were critical to the evolution of the U.S. semiconductor industry.

A lack of skilled immigrants will cripple America’s strategic industries

The stories of Jensen Huang and Morris Chang are dramatic, but they’re far from unique.. Xiaoxia Zhang, a key inventor at the American semiconductor company Qualcomm, was born in China and came to the U.S. to do her PhD at Ohio State. Lisa Su, president of the U.S. chip design company AMD, and widely regarded as being responsible for the company’s turnaround, was born in Taiwan and immigrated to America at age 3 (by coincidence, she’s also Jensen Huang’s cousin). And so on.

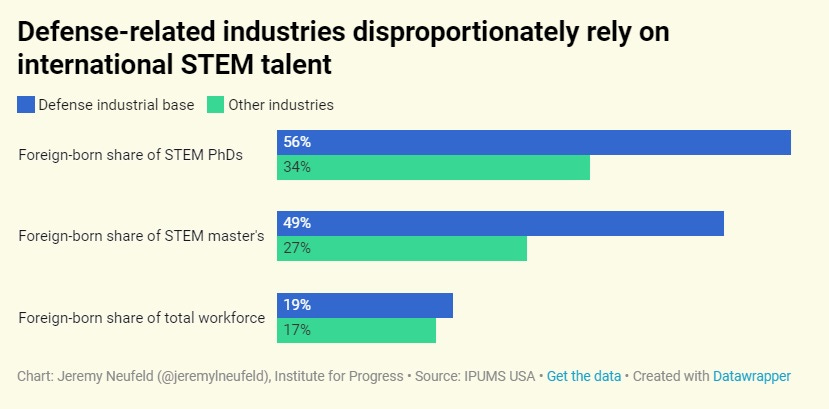

But it’s not just at the top level where America’s chip industry is powered by immigrants – and where a lack of skilled immigrants threatens its future. As the Center for Strategic and Emerging Technologies notes, the entire industry, from top to bottom, depends critically on foreign-born workers:

Approximately 40 percent of high-skilled semiconductor workers in the United States were born abroad. India is the most common place of origin among foreign-born workers, followed by China…In 2011, 87 percent of semiconductor patents awarded to top U.S. universities had at least one foreign-born inventor.

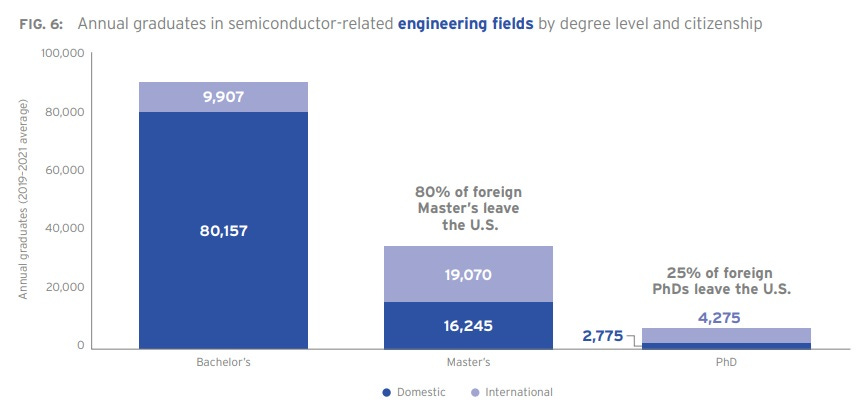

At the Master’s and PhD levels, a majority of the people getting degrees at U.S. universities in fields relevant to chipmaking are immigrants. Most of those Master’s graduates, and a significant chunk of the PhDs, end up leaving the U.S. and taking their talents elsewhere – much as Morris Chang did.

The Institute for Defense Analysis has a detailed breakdown of where the U.S. gains and loses talent. As Trump intuited, the biggest loss by far is from foreign students returning to their native countries after graduation.

And that’s as things stand today, with the U.S.’ shrunken chip manufacturing sector. To rebuild this industry as planned, the U.S. is going to need a lot more workers – technicians to operate fab equipment, engineers to design and improve it, and PhDs to research better ways to make chips. And while many will be trained domestically, the sheer size of the endeavor means that many will have to come from overseas.

The Semiconductor Industry Association has many recommendations for training more native-born workers, but at the same time it estimates that about half of the needed talent for the U.S. semiconductor push will be available domestically, even with a big push to educate more native-born Americans in chip-related fields. The rest of the demand will either be met by immigration, or not at all. The gap is bigger at the higher levels of skill:

The total number of additional workers the SIA estimates will need to be brought in is about 67,000.

In fact, the chip industry is only one of many industries that are hurting because of the talent the U.S. is letting go. Semiconductors are an especially strategic sector, but there are plenty of others – AI, batteries, biotech, advanced manufacturing, and so on – that are in much the same boat. Defense-related industries – which the U.S. is going to need to scale up to keep pace with China – are especially reliant on foreign STEM talent:

The critical AI industry is especially reliant on foreign talent – not just for workers, but for research and entrepreneurship as well. About two-thirds of AI companies in the U.S. were founded by immigrants and “70% of full-time graduate students in fields related to artificial intelligence are international.” These are researchers and entrepreneurs like “Godfather of AI” Yann LeCun, Google Brain co-founder Andrew Ng, and Coursera co-founder Daphne Koller.

To defend itself and sustain its high-tech advantage, the U.S. needs as many of these STEM workers as it can get. But it’s losing an increasing number of them after graduation every year:

The loss is less severe at higher levels on the skill ladder. But still, a quarter of foreign-born U.S.-trained PhDs end up leaving America after they get their degrees!1

Now we should note that even without strategic considerations, it would still be great for the U.S. economy if it could retain more of the skilled workers it educates and trains. A large amount of research shows that STEM worker immigration is among the most effective policies in terms of promoting innovation. Evidence also suggests that skilled immigrants increase the wages of native-born Americans, by luring investment and by starting their own companies.

But that aside, the U.S. does have a strategic imperative for admitting and retaining a lot more skilled immigrants. In order to maintain its high-tech edge and sustain its defense industries, America must improve its recruitment system.

Leveraging new and underused visas for STEM talent

Most proposals for recruiting more foreign-born STEM talent, especially in the chip industry, rely on temporary work visas. These are visas like the H-1B that allow people to come work in the U.S. temporarily – the H-1B, for example, lets a worker stay for a maximum of six years and has an annual cap of 85,000. There are other temporary visas like the O-1 visa, for exceptionally skilled individuals, that are uncapped and allow indefinite extensions, but they have to be constantly renewed on an annual basis after an initial 3-year period.

Since 2022, the Biden administration has been trying to expand the number of STEM workers who can use various temporary visas. For example, it has clarified the eligibility criteria to enable greater access for O-1A visas, expanded the J-1 “exchange visitor visa” to account for a wider pool of STEM talent, and increased the number of STEM fields in which foreign students are allowed to work during their studies. These are good, and more efforts along these lines are warranted. But overall, the effect is marginal – the increase in O-1A visas, for example, was only around 2000 per year since 2021. Another way to move the needle on skilled immigration is encouraging universities with very high research activities to play a bigger role in sponsoring J-1 STEM researchers and expanding access to the J-1 exchange visa to neighboring startups and businesses in need of skilled immigrants.

But ultimately, executive action is necessary to attract and retain the workers the U.S. desperately needs.

Legislative efforts have focused on creating new categories of temporary visas for strategic industries and regions. The most important example is the Chipmaker’s Visa, an idea created by the Economic Innovation Group that has been getting quite a bit of attention. Here’s how EIG describes the program:

The Chipmaker’s Visa program would be authorized to issue 10,000 new visas per year for 10 years with an expedited path to a Green Card not subject to complicated bureaucratic hurdles or per-country caps. This represents a concerted, one-time push…

Every quarter, 2,500 visas will be auctioned off to qualifying firms. Those firms can then utilize those visas to hire skilled immigrants, subject to an overall minimum salary level that ensures the jobs are genuinely skilled. To ensure the visas are contributing to the industry, they must be utilized by firms within a year…Once a visa is used by a particular firm, its ownership immediately transfers to the sponsored worker…Firms that have Chipmaker’s Visas can compete with each other to hire the best talent from abroad or from U.S. universities, incentivizing higher pay and more efficient allocation of the limited supply of skilled, specialized workers to where they are truly needed…

The Chipmaker’s Visa’s longer-than-usual term will give firms certainty that they will have sufficient time to scale-up their investments in the U.S. and train domestic workers…[T]he Chipmaker’s Visa will have a smooth, seamless path to permanent residency for anyone who earns at the 75th percentile of personal income (about $80,000 in 2021) for five consecutive years[.]

This is a great idea, and Congress should definitely approve it. But by itself it’s insufficient to address America’s needs, even just within the chip industry. 10,000 foreign workers is far less than the 67,000 the Semiconductor Industry Association estimates will be needed to fulfill the big push of the CHIPS Act. Even if the SIA is overestimating the number of foreigners it needs, 10,000 is extremely unlikely to be enough.

Second of all, the Chipmaker’s Visa applies only to a single industry. It could potentially be a model for targeted visas for other industries like AI, defense manufacturing, etc. – especially since it includes clever fixes for all of the well-known problems with older visa categories like the H-1B. But even if other similar visas can be designed, that’s a process that will take many years.

The U.S. needs more skills-based green cards to win the global talent war

Fundamentally, temporary work visas simply fail to address the long-term problem of talent retention. Students going back after getting their degrees is a tragic loss of human capita for the U.S.; chip workers being forced to go back en masse after spending years learning how to make chips at top U.S. companies is an absolute disaster. The example of Morris Chang, who worked in the U.S. for decades before leaving for Taiwan to found TSMC, is instructive.

Obviously the U.S. will not be able to retain every chip worker who comes here. But forcing them out, when most of them would rather stay, is foolishness. And yet temporary visas, if not followed by permanent residency, do exactly that.

It’s permanent residency – skills-based green cards – that the U.S. really has to expand. Currently, these are limited to around 140,000 per year in total. That hard cap applies to the total of all employment-based green cards, including the EB-2 category that the Biden administration has been trying to use for workers in strategic industries. If that 140,000 number is not increased, any increase in temporary visas will automatically mean more STEM workers being forced out of the country.

Increasing the employment-based green card cap will require an act of Congress. More than that, it will require a rethinking of how America approaches skilled immigration. The U.S. has to start seeing skilled foreign recruits as complementing skilled native-born American workers instead of competing with them. The idea that skilled foreign workers should be only a temporary expedient, to fill jobs for which no American worker can be found, has to be discarded.

And in fact, this is absolutely true. If the U.S. chip industry fails for lack of immigrant workers, native-born American workers in the industry will suffer – as will Americans in general, who will live in a poorer, more defenseless country. The same is true for AI, defense manufacturing, and every other strategic industry. Foreign workers are not disposable tools, nor are they the competition – they are recruits to Team America, indispensable allies in the battle to make the U.S. stronger, richer, and more secure.

In the past, attempts to increase the skills-based green card cap have been included in attempts at comprehensive immigration reform – huge omnibus bills that address every immigration issue at once, from border security to amnesty and so on. We believe that the U.S. can’t afford to wait for that approach to finally work. The border and amnesty are highly contentious issues; skilled immigration is an area of wide and deep agreement.

Thus, Congress should act specifically on skilled immigration, with a narrowly targeted bill increasing the employment-based green card cap by a substantial amount, and allocating the new extra green cards to companies in strategic industries. The increase should be at least 100,000 – enough to stop the majority of the talent losses of STEM graduates and temporary visa holders who are forced to leave the country, and enough to provide for the future needs of both the chip industry and other strategic sectors. At the same time, Congress should abolish or relax the country-specific cap on employment-based green cards, allowing the U.S. to take advantage of more talent from India and other very large countries with deep talent pools.

The purpose of this change is simple: to get America the human capital it needs to compete effectively with the People’s Republic of China in high-tech and defense-related industries. It is neither a humanitarian luxury nor an attempt to alter American politics or society. It is simply a thing that the U.S. needs to do if it wants to remain a leading power over the next half century.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this post erroneously claimed that three quarters of foreigners who get their PhDs end up leaving the U.S. after graduation. The actual number is only one quarter.

PLease consider submitting a shorter version of this essay to the Op-Ed of either the Wall Street Journal or NY Times.

As an immigrant who first came here as an exchange student in 2003, and is now a citizen, the point about Green Cards is exactly correct. Being on a student or temporary work visa and beholden to your school or employer for legal status is one thing, but it wasn’t until I got my Green Card in 2012 that I really felt like an American, with a real and concrete stake in the country. Trump’s idea is a good one, and I hope he follows through with something like it, because without permanent legal status any immigrant is only one life event away from leaving for good.