Roundup #77: The Fix-Everything Button

BART fare gates; AI and jobs, again; Tariffs and trade deficits; Jon Stewart vs. the economists; H-1Bs; Japan's fiscal position

Welcome to another roundup of interesting news and events from around the econosphere, from my traditional, 100% handcrafted human-written blog.

First, here’s an episode of Econ 102 for you! As regular readers know, Econ 102’s regular run has ended due to my co-host getting extremely busy with his new job. But we will still come out with an episode every now and then. This episode is about how cameras can improve public safety — and whether they should:

Anyway, on to this week’s list of interesting things.

1. Fixing public spaces is actually pretty easy

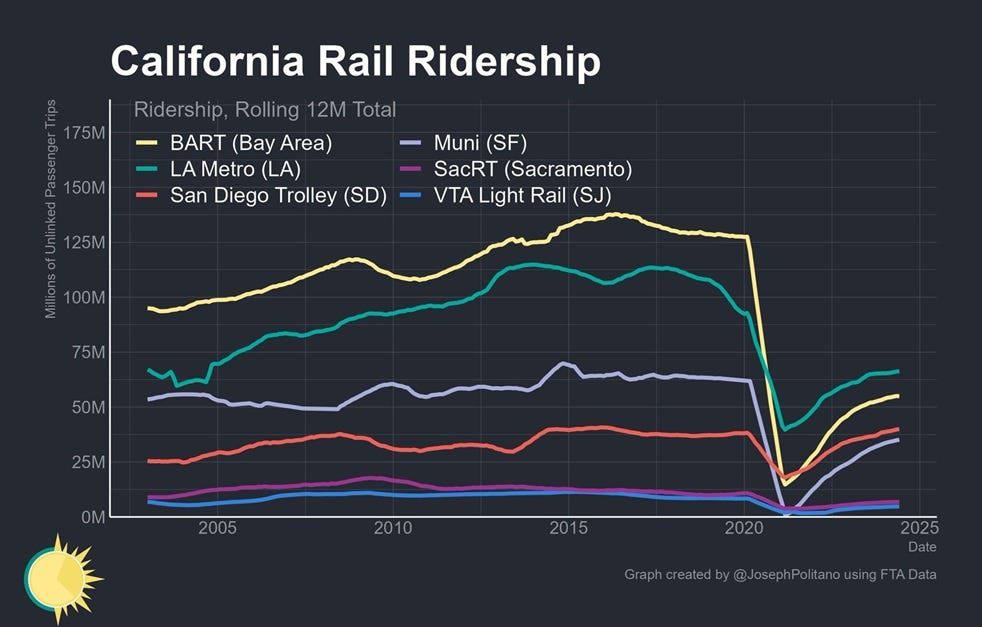

The Bay Area Rapid Transit system (BART) is in a parlous state. Ridership has plummeted in recent years; it did not even come close to fully bouncing back after the pandemic.

If BART doesn’t get bailed out with higher taxes, it will have to close stations, reduce service, and lay off workers.

Why did so many people stop riding BART? It’s possible that the pandemic permanently shifted people’s tastes; maybe people just got used to taking Uber or driving instead of using the train. But it’s also possible that the general increase in public disorder in the Bay Area just made BART unacceptable as a mode of transportation. It seemed like every train had its share of shady characters, drug users, vagrants, and the mentally ill.

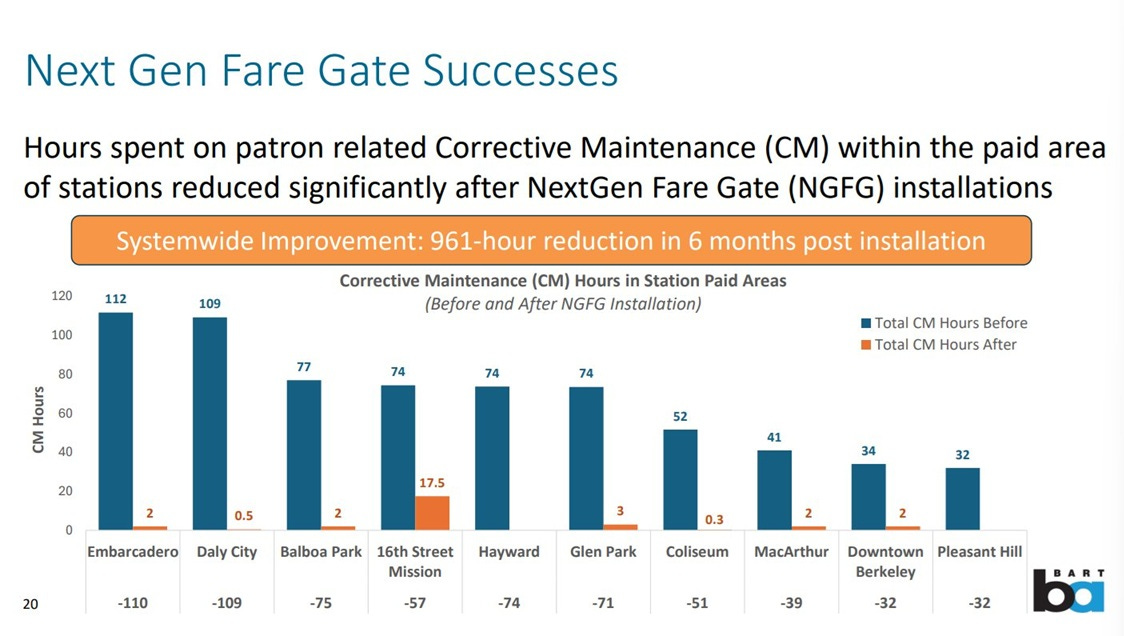

For a long time, everyone talked about this, but no one had the hard evidence to prove it. Well, now we do. After BART installed fare gates last year at many of its stations, crime on the trains plummeted by 54% in a single year.1 What’s more, the amount of time that BART employees have to spend on “patron related Corrective Maintenance” — i.e., fixing or cleaning up things that riders break or defile — went from huge amounts to almost nothing:

It turns out that just a few riders were causing most of the disorder on the BART — and those riders were mostly not paying their fares, since the fare gates were effective in stopping them.

This demonstrates a general principle: You only have to restrain a very small number of people in order to maintain public order.

Progressives often argue against measures like fare gates, labeling them “carceral” and “racist”. This demonstrates a principle that I call anarchyfare — the idea that eliminating society’s rules serves as a kind of welfare benefit for marginalized people. But in fact, most poor and marginalized people are just peace-loving people who need to ride the train to get to work. They are the chief victims of the tiny number of chaotic individuals who destroy the commons and make public spaces and public services unusable.

BART’s lesson should be applied throughout much of our society. Restraining a very few uncontrollable and chaotic individuals makes life much better for the poor and working class.

2. Is AI taking our jobs yet?

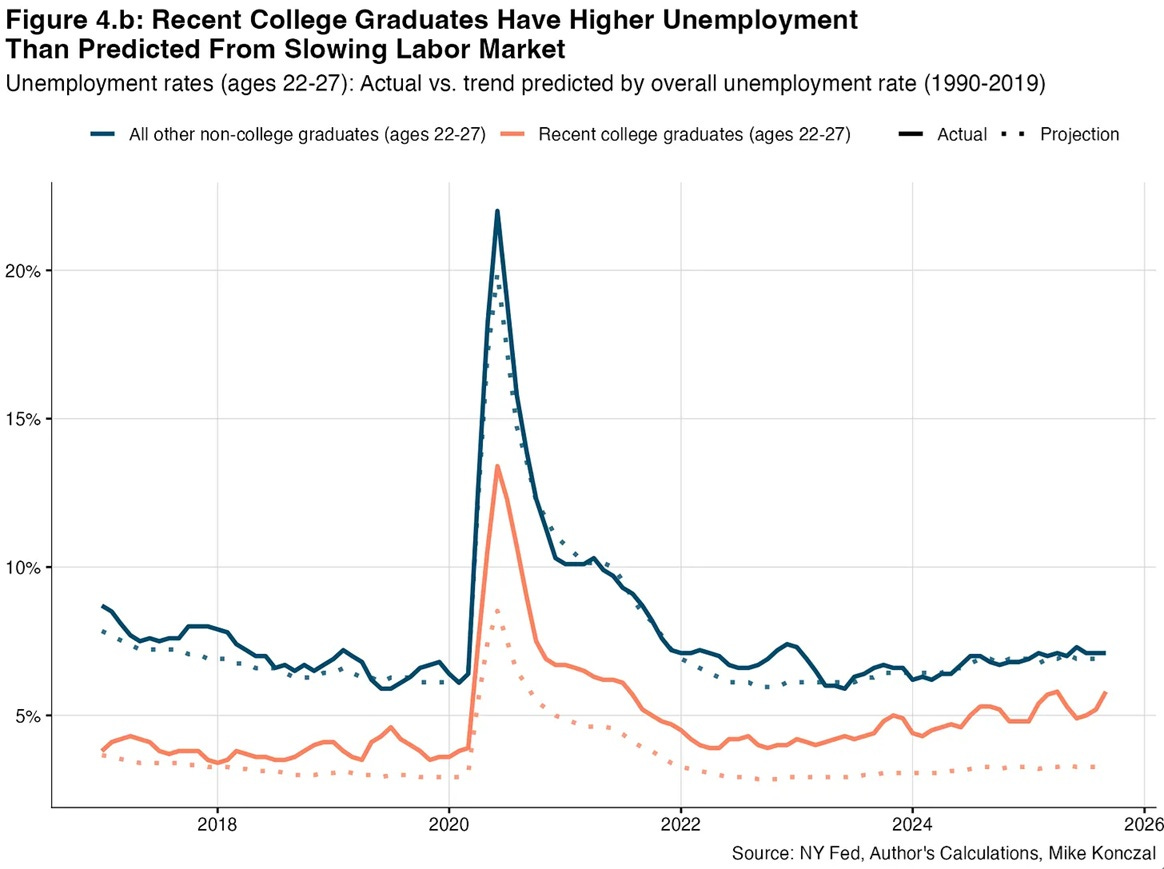

As agentic coding apps wow the world, it’s time for yet another round of “Is AI taking our jobs yet?”. Most of the attention has been focused on young college grads. The story here is that so far, AI primarily automates knowledge work — software engineering, legal services, and so on — and so impacts white-collar entry-level hiring more than other types of hiring.

This was the thesis of Brynjolfsson et al. (2025). And it’s the subject of a new post by Mike Konczal:

Konczal writes:

As you can see, people without college degrees who are 22-27 more or less track exactly what we’d expect given the labor market slowdown. But young college is much higher than our trendline we’d expect from the slowdown.

To be clear: college-educated unemployment is still lower than non-college unemployment, and everyone’s unemployment is up…What’s unusual is the gap between where college unemployment should be historically and where it actually is today…[Y]oung people have higher unemployment than we’d expect at 4.4% overall unemployment. It’s especially higher at its peak and throughout their 20s for people with a college degree. Their recent unemployment rate is historically a surprise. The bad kind of surprise.

He doesn’t claim that we know it’s AI causing the change in the historical pattern, but it’s heavily implied.

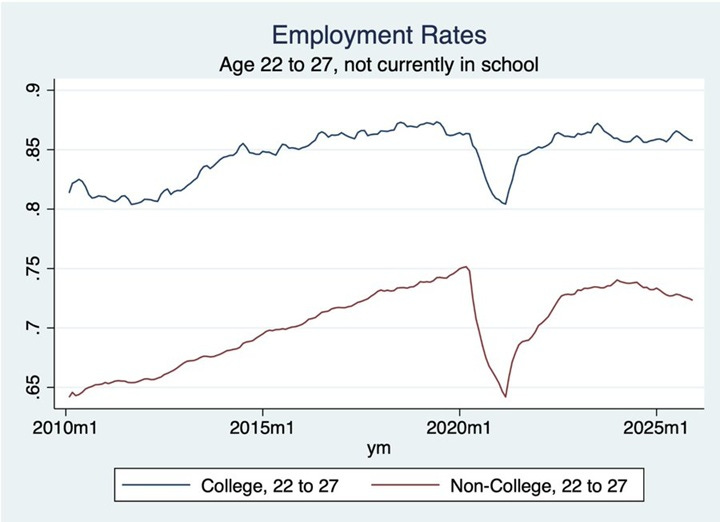

But Adam Ozimek points out that this story depends on using unemployment rates. If you look at employment rates instead, the picture looks very different:

You’d think employment rates and unemployment rates would just measure the same thing, right? But they don’t. The way our government calculates things, the employment rate is the percentage of people who have a job. The unemployment rate is the percentage of people who don’t have a job but are looking for a job. In other words, the unemployment rate depends on who says “I’m looking for a job right now”. The employment rate does not depend on this.

In fact, as Ozimek shows, recent college grads have shown pretty constant labor force participation (i.e. they’re all still trying to find jobs), while a number of non-college people of the same age have stopped looking entirely. This shows up as higher unemployment for the college grads, even though the gap in terms of “who has a job” has actually widened since the release of ChatGPT.

This simple observation throws a lot of cold water on the idea that AI is taking jobs from young college graduates. As if that isn’t enough, Zanna Iscenko has a good post that casts even more doubt on the thesis. Iscenko points out that the jobs that are typically reckoned to be more “AI exposed” also tend to be more sensitive to macroeconomic swings:

“AI exposure” and “interest rate sensitivity” are deeply correlated variables…[O]ccupations in the top quintile of AI exposure are overwhelmingly concentrated in…the most AI-exposed quintile…These are precisely the sectors most sensitive to capital costs and broad economic uncertainty. This finding is supported by existing economic literature, such as research by Gregor Zens, Maximilian Böck, and Thomas O. [Zörner] (2020), which found that workers in tasks that are easily automated are also disproportionately affected by conventional monetary policy shocks.

Further supporting the interpretation that AI exposure is correlated with sensitivity to macroeconomic shocks is the fact that we also see more pronounced drops in job postings for “AI-exposed” occupations during the hiring slowdown in early 2020…when Generative AI could not even theoretically be the explanation for the difference.

It still looks to me as if the slowdown in new-grad hiring is not a great example of AI taking jobs. I understand why everyone is worried about this, and I do think it’s plausible that many people will have to find new jobs in the age of AI. On top of that, it seems easily possible that uncertainty about the effects of AI could slow hiring, even if people don’t end up being replaced.

But I just don’t think there’s good evidence that it’s happening yet. Perhaps this year will be the year.

3. Are tariffs reducing America’s trade imbalances?

Tariffs aren’t creating a wave of manufacturing jobs for Americans; in fact, manufacturing jobs are decreasing. But it’s also worth asking whether tariffs are even having an effect on America’s overall trade deficit. Recall that Trump thinks trade deficits are bad in and of themselves — a sign of American “defeat” in a global competition, and a way in which America is dependent on foreigners.

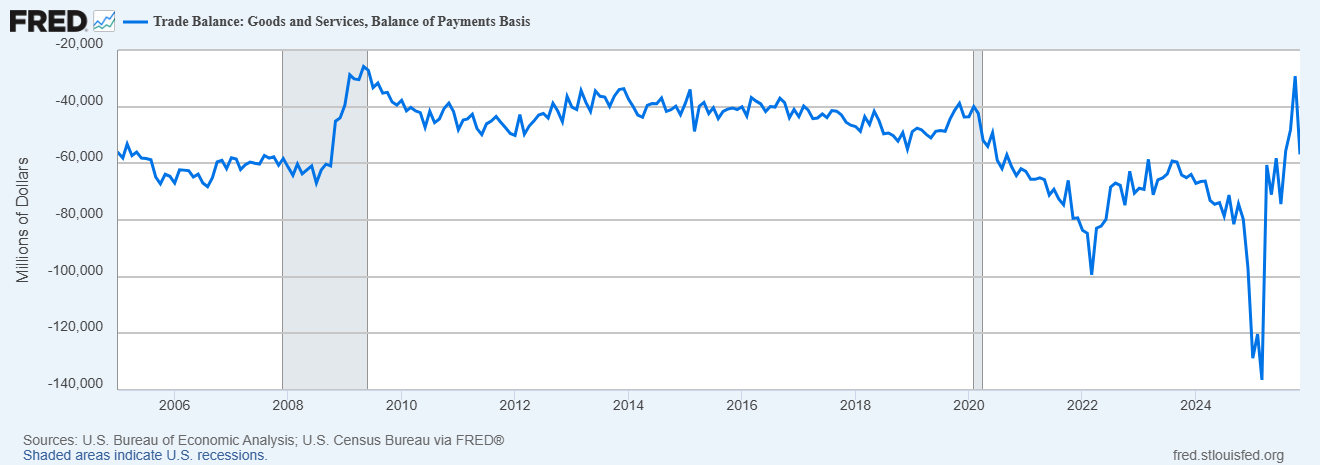

The effect of the tariffs on trade deficits doesn’t appear for a little while. At first, everyone tries to front-run the tariffs by importing as much as they can before the tariffs go into effect, leading to a giant temporary spike in the trade deficit. But after that temporary effect abated, it looked like U.S. trade deficits were shrinking:

The November data throws a bit of cold water on that idea. Imports soared and exports fell. November might turn out to be an anomaly, but so far, it doesn’t look like tariffs have done much to trim America’s trade deficit.

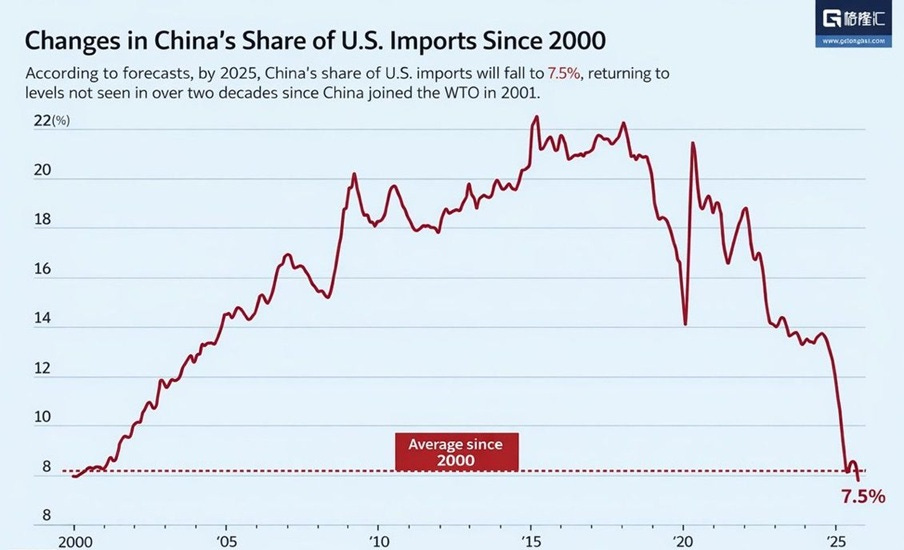

But the U.S. bilateral trade deficit with China has come down a lot. The percentage of U.S. imports that come from China has been falling since the pandemic, but it absolutely fell off a cliff after Trump’s big tariffs were announced. America used to get more than a fifth of its imports from China; now it gets less than a thirteenth:

Some people claim that China is just shipping more goods to America indirectly, through third countries like Vietnam. But Gerard DiPippo looked at which goods China has started selling more of to third countries, and found that transshipment to America can’t be very high:

By comparing the decline in China’s exports of specific goods to the United States with the increase in its exports of those same goods to other markets, we can approximate how much of China’s exports are being diverted. By this method, about 82 percent of China’s lost exports to the United States found alternative markets in the second quarter…The top destinations for those diverted exports are Southeast Asia and Europe. Comparing those trade diversion estimates with the increased U.S. imports of those same goods from those regions, we can estimate a maximum for potential transshipment into the U.S. market. By that metric, Southeast Asia is the top potential source of transshipped goods. Overall, potentially transshipped goods during the second quarter equal 23 percent of China’s diverted trade, suggesting that Chinese exporters have, at least so far, mostly found alternative markets.

True transshipment is likely lower than the 23% number that DiPippo cites as an upper bound.

What’s more plausible is that China is shipping intermediate goods — parts, materials, etc. — to countries like Vietnam, who assemble the inputs into consumer goods and sell them to the U.S. But while this means that the U.S. is still dependent on China for some types of technology, the actual manufacturing base is migrating out of China — which is good for the rest of the world, since it’ll help other countries industrialize. Also, having assembly outside China reduces America’s geopolitical vulnerability somewhat.

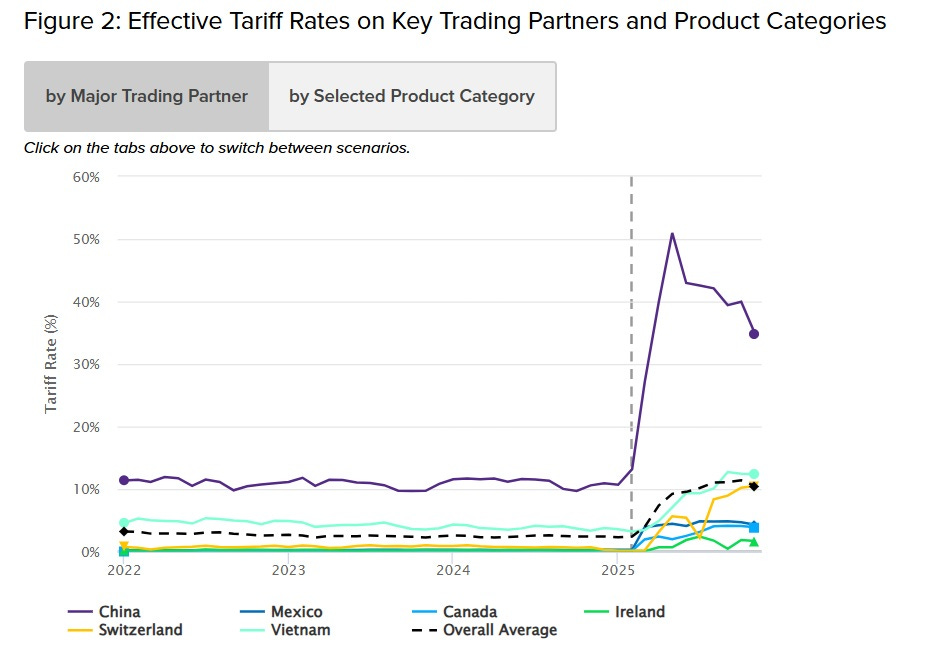

So while tariffs haven’t clobbered the trade deficit or led to a manufacturing renaissance, they do appear to be working to decouple the world’s two largest economies. Recall that the tariff rate on China is still much bigger than the rate on other countries:

If you view import dependence on China as a geopolitical risk, then this is a positive result for tariffs.

4. Why is Jon Stewart attacking economics?

Jon Stewart was my favorite political comedian when I was younger. He didn’t always get everything right, but he could almost always make you laugh, and it was clear that his heart was in the right place. He just wanted to see America succeed and Americans be happy.

But in recent years, this admirable desire has slowly morphed into a kind of lazy centrist populism. One of Stewart’s occasional targets is the economics profession — a favorite punching bag of left-populists everywhere. But because Stewart doesn’t know much about the field of economics, or what economists do, or what economics is about, or what economics research actually says, his critiques often feel uninformed and fall flat.

Jerusalem Demsas saw a recent Stewart interview with behavioral economist Richard Thaler, and decided she had finally had it with the former Daily Show host:

Stewart interjected…“But that’s not economics, economics doesn’t take into account what’s best for society!”…“The goal of economics in a capitalist system is to make the most amount of money for your shareholders. So my point is, since when is economics about improving the human condition and not just making money for the companies that are extracting the fossil fuels from the earth?”

At this point it became clear that Stewart has conflated the entire field of economics with a half-remembered, left-wing caricature of capitalism…Throughout the interview, Stewart seemed to believe that economics is just a sophisticated justification for letting rich people and corporations do whatever they want. And this total lack of basic understanding renders him an inept translator of politics and an ineffective force for the very policies he says he supports.

Demsas noted a hilarious moment in the interview in which Stewart rejects the notion that economists have anything useful to say about climate change, and then immediately endorses a cap-and-trade scheme — something economists invented. It’s as if a talk show host rejected the science of physics by saying we didn’t need physics equations to land on the moon.

Jason Furman, an incredibly mild-mannered and affable guy, was nevertheless willing to vent about his own interview with Stewart:

Meanwhile, in order to get some backup for his newfound crusade against the economics profession, Stewart has recruited Oren Cass, a Trump supporter and big fan of tariffs who spends much of his time yelling about how economists don’t know anything. I have written in the past about the utter vapidity of Cass’ critiques of economics. Every time I see a story about how U.S. manufacturing employment keeps falling and falling, I tweet to him and ask him whether he has revised his belief that tariffs help manufacturing. He never answers.

Anyway, the point here is that although Jon Stewart’s style of comedy is great for making fun of American politics, it’s not an effective or interesting way to address economic policy challenges. Unfortunately, the “econ is fake” meme has given a lot of people permission to treat those challenges as if they’re a simple matter of common sense. They are not.

5. Hire them here or hire them there

Trump and the MAGA movement aren’t just going after illegal immigrants; they’re also opposed to high-skilled legal immigration. The administration’s main target on that front has been the H-1B visa, which brings smart people to work in U.S. tech companies. Most H-1B recipients are from nonwhite countries, with India taking by far the biggest share. Trump has implemented a huge fee for hiring H-1Bs, and other GOP politicians are also trying to curb use of the visas.

Proponents of skilled immigration, such as Yours Truly, have long warned that if companies can’t get talent to come to America, they’ll simply set up overseas offices and take advantage of talent there. In fact, Glennon (2023) has evidence that this is exactly what happens:

How do multinational firms respond when artificial constraints, namely policies restricting skilled immigration, are placed on their ability to hire scarce human capital?…[F]irms respond to restrictions on H-1B immigration by increasing foreign affiliate employment…particularly in China, India, and Canada. The most impacted jobs were R&D-intensive ones…[F]or every visa rejection, [multinational companies] hire 0.4 employees abroad.

Well, it’s happening again:

Alphabet Inc. is plotting to dramatically expand its presence in India, with the possibility of taking millions of square feet in new office space in Bangalore, India’s tech hub…

US President Donald Trump’s visa restrictions have made it harder to bring foreign talent to America, prompting some companies to recruit more staff overseas. India has become an increasingly important place for US companies to hire, particularly in the race to dominate artificial intelligence…

Google rivals including OpenAI and Anthropic PBC have recently set up shop in the country…

For US tech giants, India offers a strategic workaround to Washington’s tightening immigration regime. The Trump administration has moved to sharply hike the fees for H-1B work visas — potentially to $100,000 per application — making it harder for companies to bring Indian engineers to the US.

This shift is fueling the growth of so-called global capability centers, or technology hubs operated by multinational corporations across sectors from software and retail to finance. Many of these centers are now focused on building AI products and infrastructure. Nasscom, India’s IT industry trade group, estimates such centers will employ 2.5 million people by 2030, up from 1.9 million today.

If those jobs were in America, the Indians who are working at those jobs would be spending their money on American doctors and dentists, American tax preparers and financial advisers, American restaurants and shops. Now, instead, thanks to Trump, that money is being spent in India.

6. Japan, the giant hedge fund

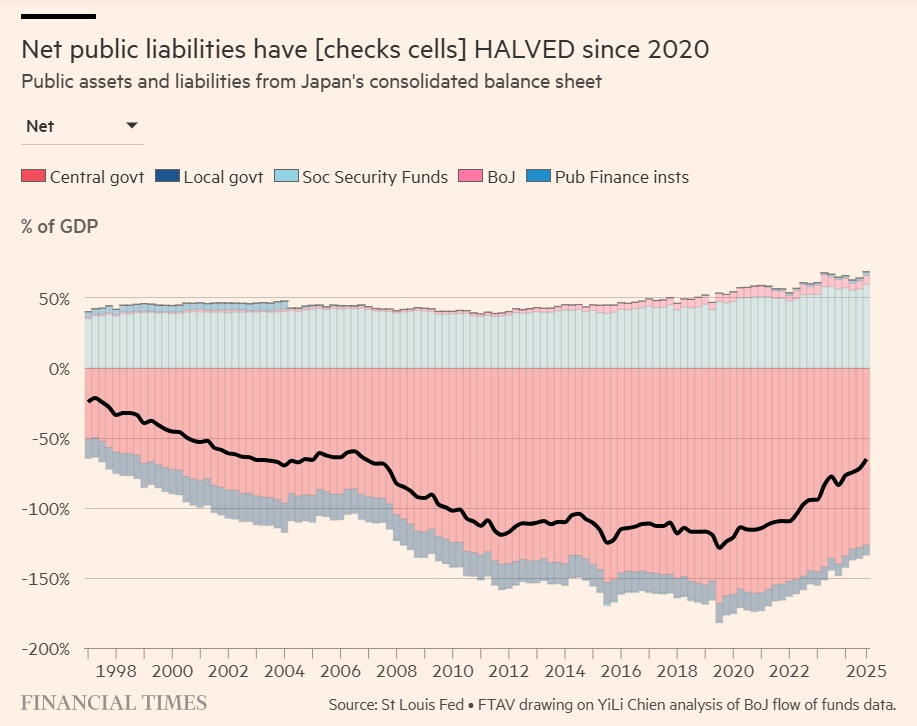

As I noted in my last post, Japan has a huge national debt. Even once you net out the portions of the debt that are held by other branches of the government, debt is only around 119% of GDP — about the same as in the U.S., which is highly indebted. But a recent post by Toby Nangle shows how Japan’s government has managed to reduce the impact of that debt by basically acting as a giant hedge fund, making huge profits on various macroeconomic “trades”:

[I]f the Japanese government had raised a bazillion yen on the bond market and funnelled it all into, say, a successful forex trading operation and a long-only stock portfolio which has gone to the moon, maybe we should consider these assets too when trying to work out what sort of parlous state Japan is actually in?…

[Japan] has enjoyed spectacular returns on its monster macro punts over the past few years…They’ve scored healthy profits on its FX interventions since 1991, which we reckon could be worth around eight per cent of GDP…The Bank of Japan’s most outlandish version of QQE has involved building a huge position in stocks, and we estimate the unrealised P&L could be worth 11 per cent of GDP…And that’s before we chalk up jumps in the value of GPIF, Japan’s $1.8tn public pension reserve fund that is maintained to help the government pay pensions. This has benefitted bigly from a combination of a slide in the yen and booming stocks…

Beyond these three, there are a host of other such trades. But pretty much all of them come down to one core basket of positions: short yen vs US dollars, and long stocks. And this trade has been wildly successful.

Nangle plays with some numbers from Fed economist YiLi Chien for Japan’s various government trading positions, and finds that they shrink Japan’s debt by around half:

The U.S. has not done anything of the sort. If George Bush had implemented his Social Security scheme in 2005, we’d be reaping many of the same benefits Japan is now enjoying…but we did not. Japan is acting like a giant — and very successful — macro hedge fund, while the U.S. keeps its money in cash under the mattress.

The fare gates are also raising millions of dollars for the BART system.

Fare gates are interesting - they work to keep fare dodgers out - however in London we have some lines without any fare gates (DLR) that seem to be just as safe and raise just as much money as the rest.

The key perhaps is lower criminality in general, cameras and ease of payment - you just tap your phone or credit card on a card reader when entering or exiting. Makes paying very easy and quick, and means that you have many stations without any permanent attendants (reducing costs significantly.

They do have occasional spot checks - where they confirm that everyone on the train has a ticket - but these are not very often. (Twice a month or so.)