The Takaichi Era begins for real

Japan is leaving its pacifist era behind. That creates some interesting economic opportunities.

Japan is a parliamentary democracy; they have a Prime Minister rather than a President. So when Takaichi Sanae became Prime Minister last October, it was because she won an internal party election, not because she received the mandate of the people. This was a problem for her, because her party — the Liberal Democratic Party (also known as Jiminto or the LDP), which is usually in power in Japan — didn’t actually have that strong of a majority. When their long-time coalition partner, a smaller party called Komeito, ditched the LDP after Takaichi came to power, some people thought Takaichi’s tenure in office might be cut short, or hamstrung by a lack of votes.

So Takaichi did the smart but risky thing, which was to call a nationwide election. That election took place yesterday. The LDP proceeded to stomp all over the opposition, winning in a massive landslide. Takaichi’s party won 68% of the seats in the lower house, giving the LDP a 2/3 majority all by itself. That’s the biggest majority the LDP has ever had in its 71 years of existence — and when you add in its new coalition partner, the Japan Innovation Party, it’s now 76%. That means Takaichi can easily push through essentially any legislation she wants, except for a constitutional amendment (and those aren’t off the table either).1 The Takaichi Era has now begun for real.

Americans have taken a bit more of an interest in Japanese politics and society lately, probably because of the tourism boom. So I thought I’d try to explain what this all means.

First, there’s the question of why the LDP always seems to win in Japan. Except for two brief periods out of power — in 1993 and 2009-2012 — the LDP has ruled Japan for the entire time since it came into existence in 1955. This almost unbroken run of victories has some people wondering if Japan is some kind of fake democracy or one-party state.

It’s not. The best book about this that I’ve ever found is Ethan Scheiner’s Democracy without Competition in Japan: Opposition Failure in a One-Party Dominant State. According to Scheiner, there are basically two reasons why the LDP stays on top. The first is that until the mid-2000s, there were some structural quirks of Japan’s electoral system that made it easier for one party to retain dominance — basically by identifying who voted for the party, and sending government funds directly to them. This is called clientelism, and it happens to some degree in most countries — think of Trump trying to starve blue states of federal government funding — but in late 20th century Japan it was easier to do. Being able to pay off reliable voter blocs — like rural construction workers — made it easier for the LDP to stay in power.

But the bigger reason that the LDP stays in power is a lot simpler and more democratic — the party is just really responsive to voters’ concerns. In the 1970s, when anger about corruption, environmental problems, and slowing economic growth almost led the Socialist Party to topple the LDP, the ruling party changed tack. It became much more environmentalist and implemented policies that helped lead to a revival of growth in the 80s.

When the bursting of the big asset bubble in the 90s led the LDP to briefly lose power, they responded with a big program of fiscal stimulus (which is one reason Japan now has so much government debt). When more scandals and the global financial crisis got the LDP kicked out in 2009, the LDP responded in 2012 by bringing in Abe Shinzo and his pro-growth economic program, which got the country working again.

In other words, the LDP simply does what any rational ruling party should do in a functioning democracy — it gives the people what they want. And the people respond by usually sticking with the known quantity, as long as it keeps being responsive. This is perfectly democratic; there’s no reason “democracy” needs to mean alternating parties in power, as long as the ruling party takes elections seriously, abides by their results, and stays in power by giving the people what they want.

This time, what Japanese people mainly wanted was security in an increasingly dangerous world. And Takaichi was the person who arose to give it to them.

For the entire time since World War 2, Japan could count on the unwavering military protection of the United States, which was the most powerful country in the world. That is no longer the case. Donald Trump is returning the U.S. to an isolationist stance; he has acted aggressively toward allies in Europe, raised tariff barriers against allies, and cozied up to Russia (which is Japan’s traditional enemy). Trump has so far continued to promise to defend Japan, and seems to really like Takaichi, but by now the whole world has learned that the mercurial U.S. leader can turn on his allies in a split second.

On top of that, a U.S. security guarantee isn’t worth what it once was. Even if America tried to defend Japan from China, it’s not clear that it could. The U.S.’ war production capability is now far inferior to China’s, and China is geographically much nearer to Japan than the U.S. is. And even if America could defend Japan against direct attack, Japan is very dependent on imports of food and fuel, and China’s submarines and missiles could potentially blockade Japan into starvation and poverty.

What can Japan do in this suddenly terrifying international environment? Most importantly, it needs to remilitarize. It needs to raise the percent of its economy spent on defense, and it needs to bring its military up to cutting-edge technology levels across the board. This will be very difficult, for reasons I’ll explain in a bit.

But it also won’t be enough. China is more than 10 times Japan’s size, and has built itself into a manufacturing juggernaut; Japan has little hope of resisting that power by itself, unless it develops nuclear weapons.2 Thus, Japan also needs to court allies to bolster its defense — not just the wavering United States, but also India, South Korea, Europe, and so on. That will take diplomatic skill of a kind that Japan is not used to summoning.

And while doing all this, Japan will need to avoid major pitfalls that could hamstring it at a critical moment. That includes economic collapse, of course. But it will also have to avoid the kind of internal social and political divisions that resulted in the election of Trump in America and have led to a rising rightist challenge in much of Europe.

Takaichi has promised to do all three of these things, and so far, she looks like she has a decent shot at pulling them off. She’s a well-known hawk on defense, and in November, she declared that Japan would act to defend Taiwan if China attacked it. China responded in rage, making various threats of war against Japan, curbing tourism, and launching a campaign to diplomatically isolate Japan by accusing it of militarism.

But China’s blitz had the opposite of the intended effect. Nobody except a smattering of online leftists and some gullible American journalists actually believed that Japan was threatening China; everyone realized it was the other way around. South Korea, recognizing the magnitude of the regional threat, and also realizing that Trump’s America wouldn’t be a reliable partner, immediately started trying to draw closer to Japan. South Korean President Lee Jae Myung went to Japan and played an impromptu drum set with Takaichi, covering some K-pop songs and producing this epic photograph:

This is an incredible diplomatic coup, especially for two countries that were at each other’s throats just a decade ago over wartime history, colonization, and a territorial dispute. Korean and Japanese people themselves have become much warmer toward each other in recent years, but for the two countries’ leaders to be so openly chummy shows how committed they are to the partnership.

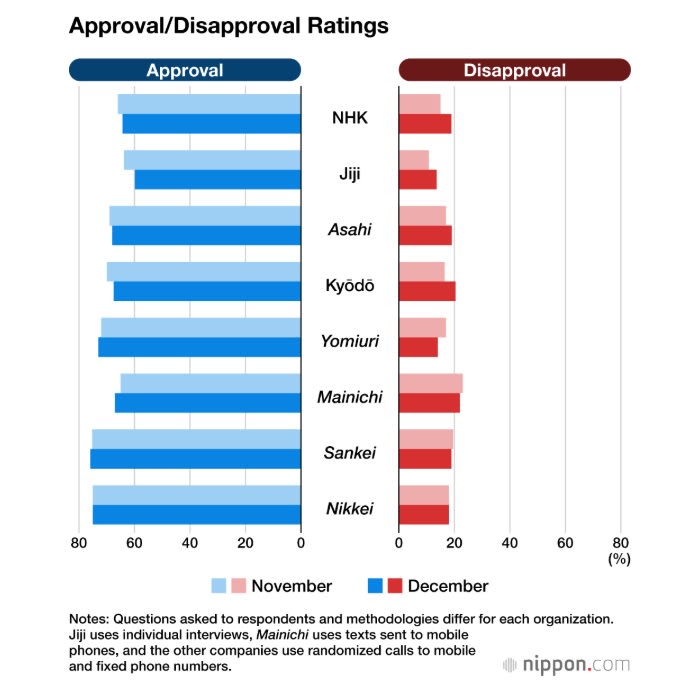

Meanwhile, China’s aggressive bullying campaign united Japanese society behind Takaichi. Various recent polls have her approval rating anywhere from the low 60s to the high 70s:

And these polls find even greater support among young Japanese voters, with some logging over 92% approval. That’s absolutely wild. There have been many articles written about why young Japanese people love Takaichi so much, but I think one reason is simply that she offers them the promise of security in a scary world.

Takaichi is also known as a conservative on the issue of immigration. But she’s no Trump. She has promised to improve immigration screening, toughen requirements for naturalization (which were very easy), make some visa requirements a bit tougher, etc. This is very measured stuff, especially compared to an anti-foreign minor party called Sanseito that cropped up last year. That party looks downright Trumpian, and siphoned votes from the LDP last year.

But by triangulating the immigration issue and convincing the Japanese people that the government wasn’t deaf to their complaints about misbehaving foreigners (who are mostly tourists, not immigrants), Takaichi took the wind right out of Sanseito’s sails.3 Despite what you may hear from certain hysterical online individuals,4 Japan is going to chart a moderate course on immigration, continuing inflows to alleviate labor shortages and attract capital, while learning from Europe’s mistakes and being more selective about which people they take in.

So Takaichi rode to a record victory because she promises to stand up for Japan internationally and hold Japanese society together domestically. Now the big question is whether she can actually deliver.

First, let’s talk about remilitarization. The main obstacle to doing this is actually not the constitution’s Article 9, which formally forbids Japan from having an army. That constitutional article was “reinterpreted” in 2014 to remove almost all legal constraints on a military buildup. A bigger obstacle is that many decades of quasi-pacifism, combined with a long fiscal crunch, have atrophied Japan’s military-industrial complex.

The situation is not as dire as you might think, since Japanese companies do lots of “dual-use” manufacturing that could be shifted to war production in a crisis, and since Japan tends to have more complete internal manufacturing supply chains than America does (making it less vulnerable to a cutoff of Chinese supplies). I recommend the following post by Jesper Koll:

So the situation isn’t hopeless, but there’s a lot of work to be done, and it’s going to be very tough.

The difficulty is going to be exacerbated by Japan’s fiscal difficulties. The government has a large pile of outstanding debt, even after you account for the portion that’s held by various branches of the government itself. It has to pay interest on that debt. For a long time, interest rates in Japan were kept extremely low, which was possible because inflation was low. So paying interest on the debt wasn’t a big problem. But now inflationary pressure has returned, with inflation above 2% in recent years:

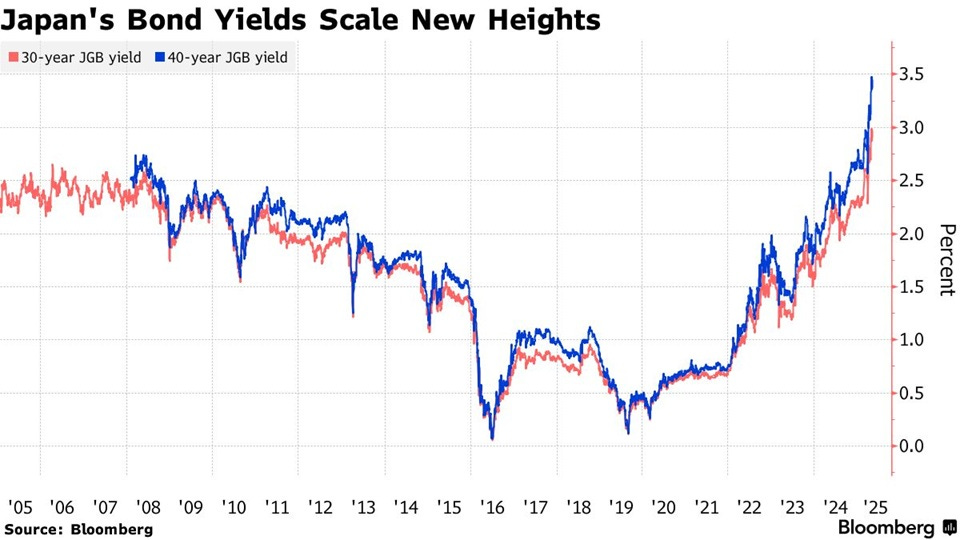

In order to prevent this inflation from spiraling upward, the Bank of Japan has to raise short-term interest rates. But that makes the government’s debt much more expensive, meaning the country has to divert a large amount of revenue toward interest payments every year. Of course, the government can just borrow to cover those interest payments, but then this drives up the debt, and raises doubts that it’ll ever be paid off. You can probably see those doubts starting to appear; rates on long-term Japanese government bonds have begun to soar:

This just makes it harder for Japan to repay its existing debt. It also threatens to hurt the economy, which would hurt tax revenue, and thus compound the problem.

Japan is in a real fiscal bind. The only way it will really be able to pay for expanded defense spending is to cut government spending in other areas — which, most of all, means benefits for the country’s burgeoning masses of elderly people. Cutting off grandma to build missiles doesn’t usually make for very good politics, but if anyone can persuade Japan’s people to accept the sacrifice, it’s probably Takaichi.

Fortunately, defense spending offers Japan some economic advantages beyond simply countering China. First of all, it offers the government the perfect excuse to wind down other, more inefficient forms of stimulus spending, like bailouts for failing companies. The Japanese economy doesn’t need stimulus at all at this point, of course, but some Japanese people will be afraid that growth will crater if spending drops. Diverting money from bailouts to defense will be good for productivity.

More importantly, defense spending will help revive Japan’s manufacturing sector, which has been under extreme pressure from Chinese competition in recent decades. Defense spending gives manufacturers a cushion from China’s export flood, and stimulates investment throughout the supply chain.

The defense imperative may also help bring Japan up from its position as a technological laggard. Japan has fallen behind, partly due to its weakness in software, partly due to the fact that most of Japan’s R&D is incremental stuff, performed by risk-averse corporations. Defense spending will allow Japan’s government to get into the game, funding bolder research efforts that benefit many companies instead of just one. It will also spur faster adoption of AI technology — out of sheer necessity — that will probably solve Japan’s software problems.

Finally, defense will be a great area for Japan to solicit greenfield investment — a big missing piece of Japan’s economy. American defense companies looking for places to make drones, ships, and missiles unencumbered by the U.S.’ legalistic regulatory state would be well-advised to build some factories in Japan, which can set them up quickly and easily, and where supply chains, labor quality, and infrastructure are all very good.

So while Takaichi has some big challenges ahead of her, she also has some big opportunities. It’s sad that Japan is being forced to leave behind its long pacifist moment. But with the right leadership, this necessary change could end up helping the country escape economic stagnation as well.

Constitutional amendments require a 2/3 majority in the upper house as well, plus a majority in a national referendum.

In fact, Japan should develop nuclear weapons, as quickly as possible. But this will be politically very challenging, given the country’s history of suffering at the hands of nuclear weapons in WW2.

This echoes the approach of Abe, who offered Japanese voters traditional conservatism while cracking down on rightists.

Some of whom may be friends of mine…