Politicized science inevitably tends toward pseudoscience

Researchers shouldn't just make stuff up.

Back when I was an economics graduate student, I learned about Real Business Cycle models. These are mathematical models of economic booms and recessions, and they rely on some fairly suspicious assumptions. In these models, recessions happen because of a slowdown in the rate of technological innovation — basically, scientists and engineers suddenly fail to make new discoveries at the same rate as before, or even forget some of what they knew. And in these models, unemployment happens because people know that technology will be advancing more slowly for a few quarters, leading to slower wage growth, and they decide to take a little time off.

That is obviously wildly unrealistic. And even by the (necessarily) weak evidentiary standards of macroeconomics, Real Business Cycle models never did a good job of fitting the data. Nevertheless, the models won their creators a Nobel prize in 2004, and versions of them are still in use in many subfields of economics.

When I asked a macroeconomist at the University of Michigan why RBC models were still so strangely popular, he shrugged and said “Politics!” RBC theory basically says that neither the Fed nor Congress can stabilize the real economy, so using things like fiscal stimulus or interest rate cuts to try to fight recessions is pointless. The macroeconomist I spoke to suggested that this feature of the models appealed to small-government libertarians, who — at least at that time — had a decent amount of clout in the economics field.

If politics really explains a large portion of the popularity of RBC models, that’s not a good thing at all. In recent years, it has become fashionable in some circles to claim that because scientists are inevitably biased, attempts to be objective are doomed and therefore pointless. But as I argued in a post back in 2021, this is utterly wrongheaded.

Yes, researchers will always have their biases, but they should always work hard to suppress those biases and be as objective as they can. If they let those biases run free, science becomes less capable of discovering facts about the world — facts that ultimately give humanity greater control over our lives.

This past week, I noticed a couple of things that only reinforce my conclusion that politically driven science tends to rapidly degenerate into unusable pseudoscience. Unlike RBC theory, these examples involved leftist politics. The first was a flowchart released by Dr. Rupa Marya, a professor of medicine at the prestigious UCSF medical school.

The UCSF inflammation flowchart

Here was the flowchart that Dr. Marya released, tweeting it along with the hashtags “#Decolonization” and #FreePalestine”:

Now, one reason this chart represents pseudoscience is that the claim it’s making is not clear at all. What do the blue arrows on this chart represent? Does the arrow pointing from “white supremacy” to “genocide” mean that all or most genocides are due to white supremacy? Does it mean that white supremacy usually leads to genocide? Or does it mean that white supremacy tends to increase the risk of genocide?

Those would all be very different things. Obviously white supremacy isn’t even close to being the only cause of genocide, as genocide long predates the idea of “whiteness” itself, and there are plenty of genocides that involve no white people at all. But you can make a reasonable case that white supremacy makes genocide more likely. That case will inevitably rest on definitions (What’s “white supremacy”? What counts as a “genocide”? Etc.), various assumptions about the direction of causality, and empirical techniques like cross-country regressions. It will be a difficult case to prove, but you could do it.

But because we have no idea what these blue arrows mean, we have no idea if this is the case Dr. Marya wants to make. In fact, because all of the arrows on the chart look the same, it’s likely that they don’t have a consistent meaning. This chart — which the UCSF professor calls a “direct acyclic graph”, despite the fact that it’s not acyclic — is simply an impressionistic flowchart of concepts that Dr. Marya feels are connected in some important way.

Certainly, some of the more natural interpretations of the chart are obviously false. For example, the chart draws an arrow from capitalism to supremacism, and from there to patriarchy. But not only is patriarchy quite common in pre-capitalist societies (feudal societies, tribal societies, traditional farming villages etc.), but we have lots of evidence of ways that capitalism weakens patriarchy over the long run. This is one of the key findings of Claudia Goldin, who won the Econ Nobel this year. One big reason is that capitalism tends to make less of women’s labor “invisible” — exactly the reverse of the arrow on this chart. In contrast, academic arguments that capitalism weakens feminism tend to be primarily theoretical.

Another example is the set of arrows from “slavery” to “cheap labor” to “capitalism”. There is a (probably wrong) theory out there that slavery facilitated the development of capitalism, but it’s undeniable that capitalism has seen its greatest flourishing after the widespread banning of slavery.

The philosopher Liam Bright doubtless had facts like this in mind when he drily released his own alternative chart:

Of course if challenged on any of these points, Dr. Marya might claim that the alleged line from capitalism to supremacism to patriarchy, or from slavery to capitalism, etc., is only one channel of causation among many. But because the chart doesn’t make it clear whether this is what it’s claiming, we don’t know how we should evaluate it.

This is the key reason why the chart is pseudoscientific. If the claims made in a chart like this are not concrete, they’re not testable. Testability is at the core of science; otherwise, theory becomes unmoored from physical reality.

(In fact, some defenders of this might even argue that testability itself is a western/colonialist value that should be rejected. This would be like when Stephen Colbert says “We know every word of the Bible is true because the Bible says that the Bible is true, and if you remember from earlier in this sentence, every word in the Bible is true.”)

Anyway, note that I am not saying that the general idea that social disparities lead to increased risk of inflammation is false or disproven or ridiculous on its face. In fact, there are studies finding correlations between self-reported discrimination and inflammation, between immigrant parenthood and inflammation, and so on. So far, these studies haven’t established causation — for example, people who have emotional problems that cause inflammation may also be more likely to perceive discrimination in everyday interactions. But you could definitely do causal studies to establish those links, and maybe the links are really there.

In other words, there’s nothing unscientific about looking for concrete causal relationships between any of the concepts on Dr. Marya’s flowchart. It’s the grandiose yet vague way in which the chart mashes all of these ideas together into a poorly defined framework that makes it pseudoscientific.

But the chart had to be grandiose, because of politics. Scientific findings, especially in medicine and the social sciences, are typically small-bore things; it’s very difficult to wring little bits of reliable knowledge from the Universe. If we find that racial discrimination exacerbates inflammation, the public health implication will be to…decrease racial discrimination, or to find some way of protecting against its effects. But that’s the kind of limited, meliorist liberal tinkering that “decolonial” politics rejects.

No, the theory has to be something big, in order to get people to dream of the grand revolutionary wars and ethnic expulsions that will presumably cleanse the Earth of settler-colonialism and capitalism and build a new decolonial socialist world. So it all has to be connected — every social system you might have a problem with, every possible leftist theory of history and sociology and economics.

And it all has to lead to inflammation, because, well, inflammation is what Dr. Marya studies, and that’s presumably why you’ve come to her office when she hands you this chart. As for whether thinking about “decolonization” or getting involved in leftist political movements will reduce your inflammation at all, well, who knows; it might work through the same mechanisms as prayer! Personally, my very unprofessional recommendation would be to take an Advil, but what do I know? I did not go to medical school.

The saga of Bulstrode (2021)

Jenny Bulstrode is a lecturer at University College London, who has an appointment in both the Department of Science and Technology Studies and the Faculty of Maths and Physical Sciences (yes, the British pluralize the word “math” into “maths”, sigh). In 2021 she wrote a paper called “Black metallurgists and the making of the industrial revolution”. In this paper she claimed that the British metallurgist Henry Cort, who famously invented the process for turning scrap iron into bar iron, actually got that technique from some Black metallurgists in Jamaica. Specifically, she speculates that Jamaican workers got the idea of passing scrap iron through grooved rollers — which is one part of Cort’s process — from the grooved rollers used to grind sugar cane.

In July, the historian Anton Howes wrote a blog post in which he lays out Bulstrode’s evidence in a concise format, and explains why this evidence is totally insufficient to support the conclusion that Henry Cort got his ideas from Jamaica. Briefly, Bulstrode speculates, without evidence, that a particular Jamaican steel mill was commercially successful because it invented a new process for turning scrap iron into bar iron. There was no evidence that they invented such a new process. Bulstrode then speculates that Henry Cort learned about this supposed new process when the destroyed pieces of the Jamaican factory were shipped to him in Portsmouth — a claim for which there is also no evidence. Howes also notes that grooved rollers for sugar had lengthwise grooves that fit together like the teeth of a gear, while the grooved rollers for scrap iron had grooves around their circumference for the iron to pass through — a very different type of groove.

In a follow-up post in August, Howes noted a 2023 paper by a history graduate student named Oliver Jelf, which goes over the sources Bulstrode uses and finds that they’re generally inconsistent with her narrative. Howes writes:

Oliver Jelf…has not only examined [Bulstrode’s] interpretation of the sources in detail, but has transcribed those same sources for anyone to read and judge for themselves…

In science terms, if you were to read those same sources before reading Bulstrode’s arguments, there is absolutely no way that you would derive the same conclusions as her . If you simply read the same primary sources that Bulstrode did and tried to create a narrative from them, I can’t see how you’d simply get anything more interesting than the following: “Reeder was the well-connected owner of a very ordinary iron foundry in Jamaica, which was profitable because it used slave labour and had very little competition on the island. In 1782, at the behest of panicked islanders, the military governor of Jamaica reluctantly razed the mill to the ground because of a rumoured imminent Franco-Spanish invasion, with some of the foundry’s weapons and ammunition temporarily brought onto British warships until the threat had passed. Oh, and in 1781 a distant relative of Henry Cort once sailed from Jamaica to Lancaster, which is nowhere near to where Cort was based in Portsmouth.” What I simply cannot fathom, now that I’ve read her sources thanks to Jelf’s transcriptions, is how Bulstrode arrived at her narrative at all.

I, however, can fathom how Bulstrode arrived at her narrative: politics. The idea that Black labor and ingenuity “built” the U.S. and other Western countries was very popular in the 2010s, as was the concept of cultural appropriation. The story of a White capitalist appropriating the inventions of enslaved Black workers is thus appealing from a political standpoint, at least if you are in a heavily left-leaning field like history. That probably explains why Bulstrode’s paper, even before the controversy, was far and away the most well-read thing that the journal History and Technology has ever published. I mean, it’s not like the paper creates some new methodology, or has much relevance to modern life (Did you really care about Henry Cort?).

The realization that Bulstrode’s paper was mostly made up prompted a widespread outcry. The journal History and Technology then published an editorial by Amy Slaton and Tiego Suraiva defending the paper. They write:

Those who dispute Bulstrode’s claims in the press and in letters to History and Technology have focused on two main issues: 1) the translation between sugar and iron technologies materialized in grooved rollers and practices of feeding bundles through them; and 2) the means through which Henry Cort learned about Jamaican processes.

In fact, this completely ignores the most important criticism: the lack of evidence that the Jamaican iron plant was able to create bar iron from scrap iron at all, instead of through typical, traditional processes for creating bar iron.

Anyway, regarding the “grooved rollers” thing, Slaton and Suraiva write:

There is no direct reference in any source quoted by Bulstrode or in the archaeological record to grooved rollers used to work iron at John Reeder’s foundry. But in the early 1780s, not only were grooved rollers for the working of iron not new (remember, Cort did not get his patent for this), but Black metallurgists were also producing iron grooved rollers to crush sugar cane in surrounding plantations…It is safe to assume Black metallurgists working at Reeder’s Pen, the main foundry in Jamaica, in the early 1780s produced both types of iron rollers, horizontal and vertical.

So after admitting the complete lack of evidence for Bulstrode’s claim about the use of the grooved rollers, Slaton and Survaiva then note that grooved rollers for ironworking weren’t even a new thing, and weren’t the novel innovation that Cort got his patent for. Which pretty much destroys Bulstrode’s whole case.

(Also, Slaton and Survaiva fail to distinguish between horizontal vs. vertical positioning of rollers, which basically doesn’t matter, and lengthwise vs. circumferential grooves, which are the key difference between the sugarcane rollers and the iron rollers. It seems like they didn’t put much thought into this point.)

Regarding how Cort could have learned about a Jamaican technique, Slaton and Suraiva write:

While the historical record does not provide again any immediate proof that Cort knew about what was going on at Reeder’s foundry, Bulstrode gives enough information for readers to appreciate how the relation between the two sites was mediated through the Royal Navy and extensive financial interests, thus sustaining the inference of the existence of knowledge traveling between the two geographies.

In other words, there’s zero evidence that Cort had heard about the Jamaican foundry at all, but both Jamaica and the city where Cort was living were part of the British Empire, so it’s safe to assume they had some sort of connection.

This is among the most sloppy inferences I have ever seen.

Anyway, at the end of their editorial defending Bulstrode’s paper, Slaton and Suraiva offer a defense that’s purely political in nature:

[Bulstrode’s] critics return repeatedly to claims that politics must not direct historical research and interpretation. To make the case, as several of our correspondents have done, that ‘facts are facts’ (and that at bottom, Bulstrode is not adhering to what they see as the facts), is to deny a foundational tenet of humanities scholarship of the last several generations: That our perceptions of objectivity themselves derive from situated experiences. All historians necessarily select the conditions, actors and materialities that they find to be significant and thus, to constitute the events of the past.

We by no means hold that ‘fiction’ is a meaningless category – dishonesty and fabrication in academic scholarship are ethically unacceptable. But we do believe that what counts as accountability to our historical subjects, our readers and our own communities is not singular or to be dictated prior to engaging in historical study. If we are to confront the anti-Blackness of EuroAmerican intellectual traditions, as those have been explicated over the last century by DuBois, Fanon, and scholars of the subsequent generations we must grasp that what is experienced by dominant actors in EuroAmerican cultures as ‘empiricism’ is deeply conditioned by the predicating logics of colonialism and racial capitalism. To do otherwise is to reinstate older forms of profoundly selective historicism that support white domination.

Basically, Slaton and Suravia assert that while you shouldn’t be allowed to fabricate sources, any speculation should be regarded as scholarship, no matter how scant the evidence, as long as that speculation supports their preferred political aims.

Note that this is far from the only place I’ve seen arguments like this in recent years. Here’s an essay in American Anthropologist, rejecting the idea of an “objective past” in favor of “counter-myths that emphasize the contingent and political nature of archaeological praxis”.

Personally, I fail to see any salient difference between insisting that we believe in fabricated sources and insisting that we believe in speculations that have nothing to do with the existing sources. Both seem, to me, like clear examples of fiction. And when fiction is treated as fact, that is pseudoscience.

Again, allowing politics to guide research is the core problem.

What’s the difference between fact and consensus?

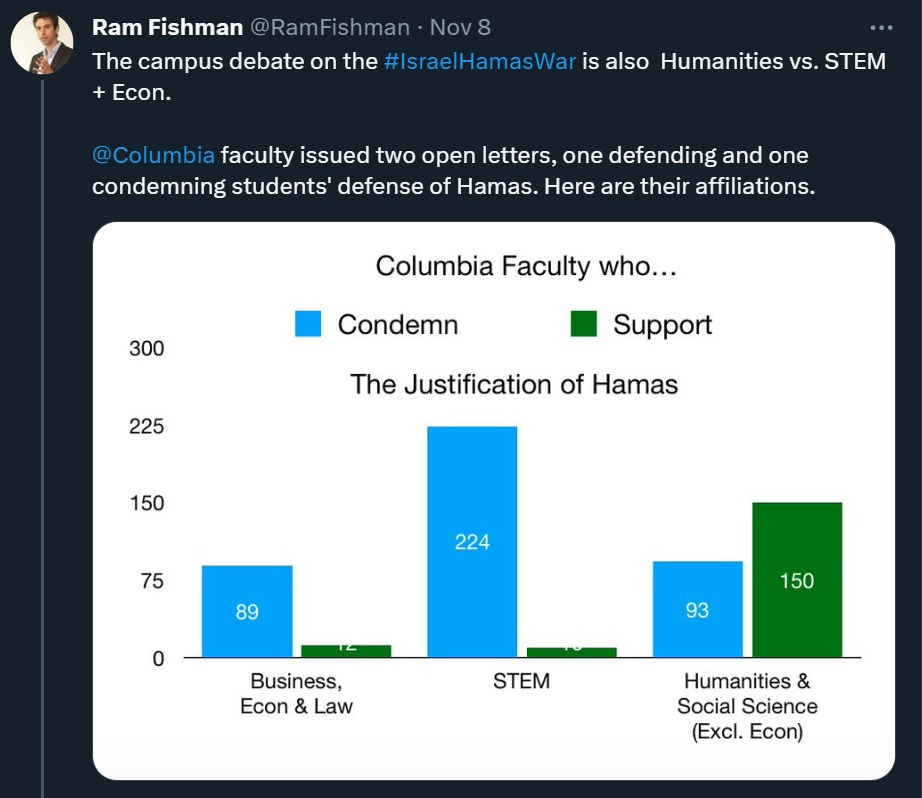

In recent years, conservatives have been arguing that leftist politics is utterly dominant in academia, creating the danger of politically motivated fake science gaining hold. While this is something worth keeping an eye on, I’m not so sure. For example, at Columbia, only in the humanities and non-econ social sciences did we see widespread support for what one might call a “leftist” view of the Israel-Gaza war, and in that case it was still fairly split:

But it’s still worth doing the thought experiment of asking what happens if an academic field becomes entirely populated by researchers who think that one particular brand of politics justifies embracing any methodology, however pseudoscientific.

One thing that can happen in that case is that society might suffer. Human consensus can’t change the laws of the Universe; nature always gets a vote. And if humans collectively decide to embrace pseudoscience in the natural sciences, it can lead to widespread suffering. A classic example is the one at the top of this post — Trofim Lysenko, a Soviet scientist who led a politically motivated crusade against the science of genetics. The results were disastrous:

Although nominally a biologist, Lysenko considered [ideas based on genetics] reactionary and evil, since he saw them as reinforcing the status quo and denying all capacity for change…Lysenko promoted the Marxist idea that the environment alone shapes plants and animals…Lysenko began to “educate” Soviet crops to sprout at different times of year by soaking them in freezing water, among other practices. He then claimed that future generations of crops would remember these environmental cues and, even without being treated themselves, would inherit the beneficial traits…

In the late 1920s and early 1930s Joseph Stalin—with Lysenko’s backing—had instituted a catastrophic scheme to “modernize” Soviet agriculture, forcing millions of people to join collective, state-run farms. Widespread crop failure and famine resulted…Lysenko forced farmers to plant seeds very close together, for instance, since according to his “law of the life of species,” plants from the same “class” never compete with one another. He also forbade all use of fertilizers and pesticides.

Wheat, rye, potatoes, beets—most everything grown according to Lysenko’s methods died or rotted…

Criticism from foreigners did not sit well with Lysenko, who loathed Western “bourgeois” scientists and denounced them as tools of imperialist oppressors…Unable to silence Western critics, Lysenko still tried to eliminate all dissent within the Soviet Union. Scientists who refused to renounce genetics found themselves at the mercy of the secret police…Hundreds if not thousands of others were rounded up and dumped into prisons or psychiatric hospitals. Several got sentenced to death as enemies of the state or, fittingly, starved in their jail cells[.]

So that’s one potential downside of politicized science. If the U.S. allows leftist politics to…er, colonize the field of medicine, we could see widespread negative health effects from politically motivated pseudoscientific treatments or diagnoses. Politically motivated pseudoscience in criminology could lead to defunding of police, and thus to increased death and victimization rates for Black people. And so on. (In fact, you can argue that Real Business Cycle models prevented us from responding more forcefully to the financial crisis of 2008, thus exacerbating the Great Recession.)

When it comes to a field like history, things are less clear. History has already happened; the study of history affects us only via the lessons we choose to learn from it. So perhaps politically-motivated fake history wouldn’t do anything to our society that the politics itself hadn’t already done.

So I think we should pay the closest attention to fields that have big implications for actual policymaking — medicine, econ, etc. The more these get politicized, the greater physical danger our people will be in.

I was aghast after reading that stupid defense from "History & Innovation." It is truly shocking that people with academic credentials should come with such risible justifications (ie. Fabricating evidence is good as long as it confronts EuroAmerica-centrism, WTF?!). Diversity of opinion and debate should be encouraged, but blatant falsifications and lies should be suppressed. So many in the Left are tempted by overly simplified notions of decolonization, anti-imperialism that they become themselves prisoners of a violent and irrational ideology. What is EuroAmericanism anyway?

At this point, I think it is crucial to defend the values and civilization of the Enlightenment. It is being attacked by both the Left and the Right. The Left wants to deconstruct the results of Enlightenment by tearing apart the very fabric of society which enables us to live in an orderly fashion. On the other hand, the Right wants to demolish the Enlightenment by bringing back traditional values (real or imagined) as an answer to modern problems.

For me, the West is the product of the Enlightenment and the result of self-reflection after two horrendous global wars. The West is not Europe, nor is it Christendom. It is a civilization forged by abstract ideals (freedom, rule of law, human rights) & real experiences (World Wars, the Holocaust). I am not European nor American, I am not even white, but I think the civilization represented by the West is worth defending and promoting. To that end, I think it is hugely important to confront this kind of pseudo-scientific nonsense as described by Noah.

Love this article but I think it’s a bit more insidious than people making stuff up. Science works off falsification and falsifiable ideas, however, there are always assumptions and methodological choices that influence how we arrive at those findings.

There is also the very pernicious file drawer effect (scrapping none significant findings) and as I have discovered first hand, some very dicey decisions made around which of the grey literature to include on meta-analyses.

Long story short, science conducted by a politically or ideologically homogenous group is like conducting a survey on who you intend to vote for with a biased sample or conducting a prosecution without a defense attorney (the later is called a grand jury and getting indictments from a grand jury is laughably easy).

A diverse scientific community will use a variety of methods, study topics differently and make different assumptions and incrementally move the different fields forward. The homogeneous blob we have in most of our sciences currently will struggle, not due to ethical reasons or by trying to hide things but simply due to a lack of diversity

of thought.