I think India can do it

A lot of people doubt that India can develop. I'll take the other side of that bet.

In 2004, The Economist predicted that India’s economic growth rate would overtake China’s in two decades. In 2010, in an article called “India’s surprising growth miracle”, they shortened that timeline dramatically, declaring that India might overtake China in terms of GDP growth as early as “2013, if not before”.

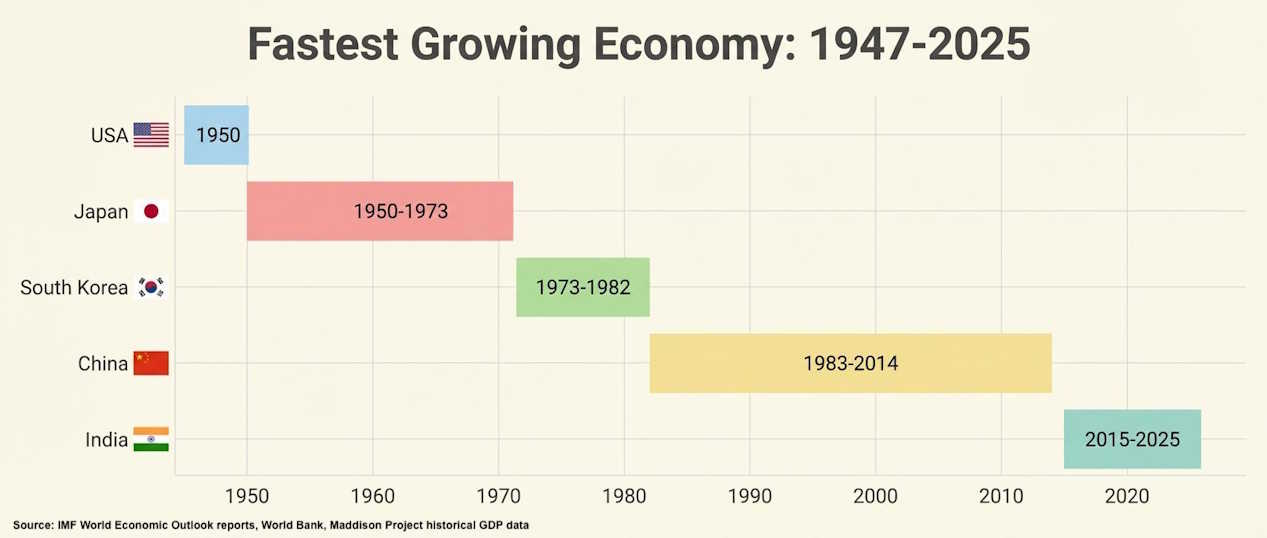

In the end, it took two years longer. Since 2015, India has been the world’s fastest-growing major economy, taking the crown from China:

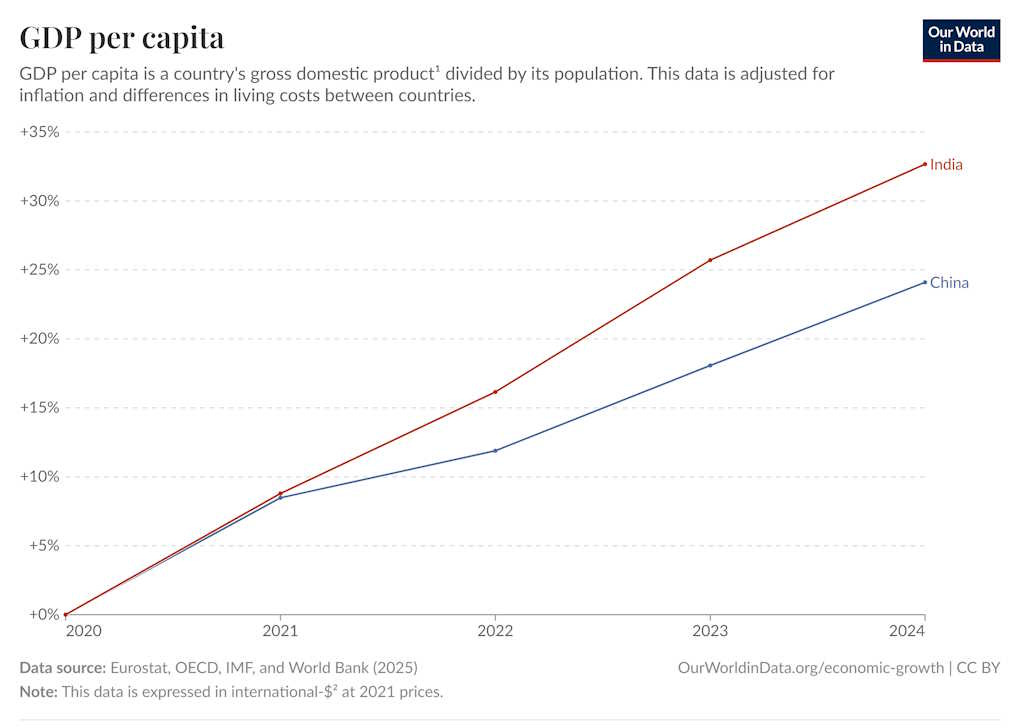

As The Economist noted, this is partly due to India’s more rapid population growth. If we want to look at living standards, we should look at per capita GDP (PPP). Here, India didn’t overtake China until after the pandemic:

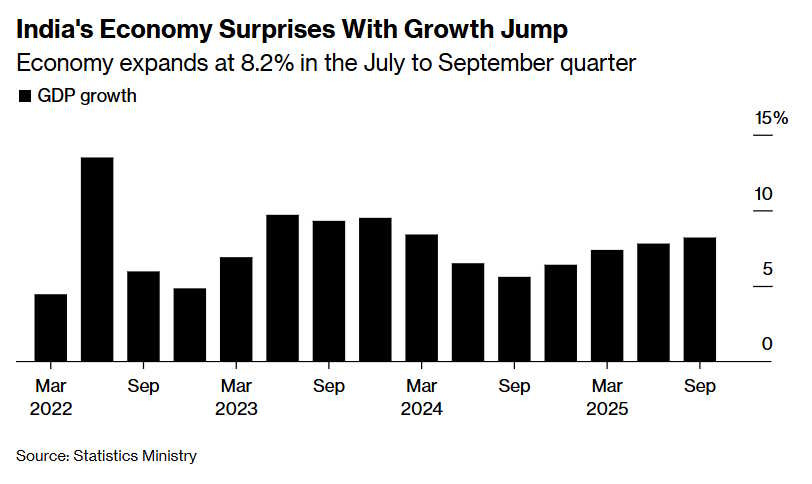

India continues to turn in strong growth performances. In the third quarter of this year, it grew at 8.2%, up from 7.8% the previous quarter:

India’s population is growing at a little less than 1% a year, so this roughly corresponds to a per capita growth rate of around 7.2% or 7.3%.

That sort of growth rate is less than South Korea or China managed during their heydays of industrialization. From 1991 to 2013, China’s per capita GDP (PPP) grew at an annualized rate of 9.4%. But 7.2% would still be enough to utterly transform India in just a short space of time.

According to the IMF, India has a per capita GDP (PPP) of $12,101 as of 2025. Thirteen years of growth at 7.2% would bring that to $29,878 — a little higher than where China is today. That’s interesting, because India’s big economic reforms happened in 1991 — twelve years after China’s. Two decades of 7.2% growth would bring India to $48,609 — about as rich as Hungary or Portugal today.

In other words, if India keeps growing as fast as it’s growing right now, it will be a developed country before kids born today are out of college.

Consider even the more modest scenario in which India grows at the same rate it’s been growing over the past decade — about 5.4% in real per capita PPP terms. Fifteen more years of that growth rate would bring India to $26,633 — about where China and Thailand are today. Twenty years, and it would be $34,644 — about the same as Chile.

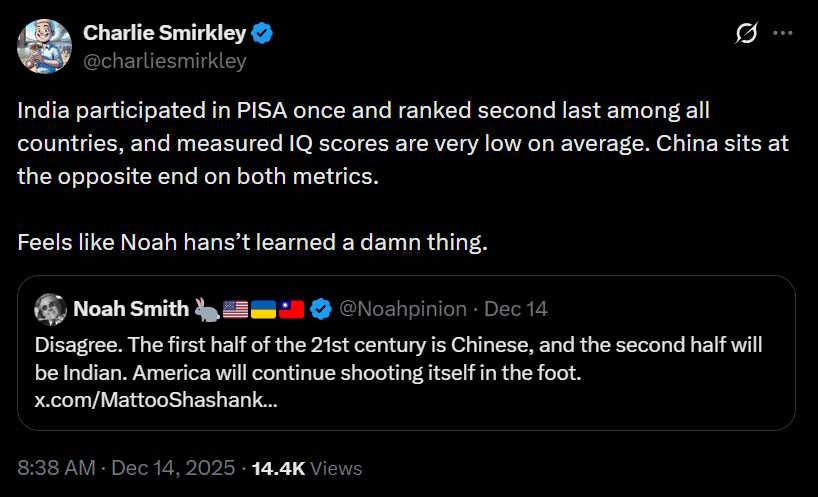

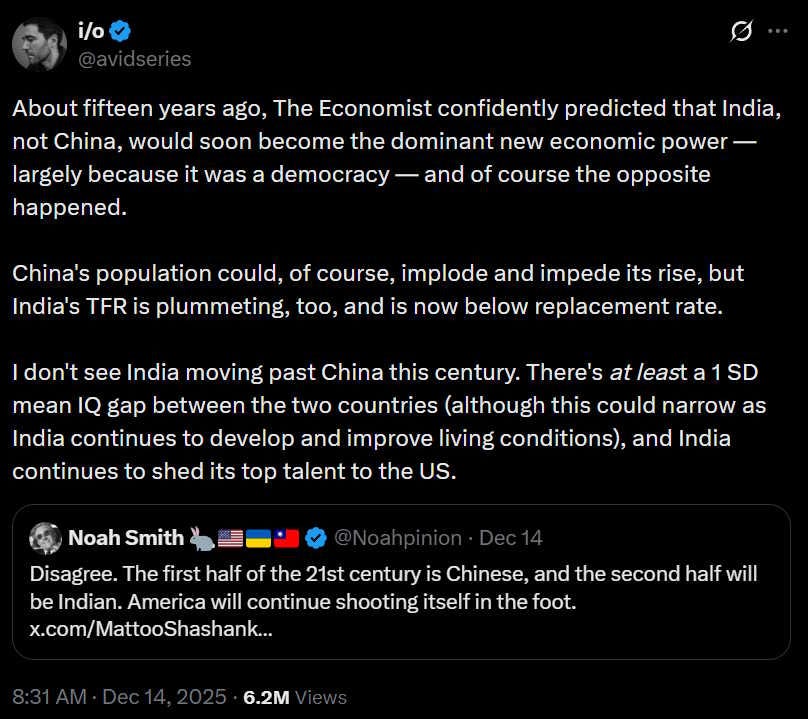

This is all a big “if”, of course. When I threw out some optimistic growth scenarios on X, I was mercilessly mocked:

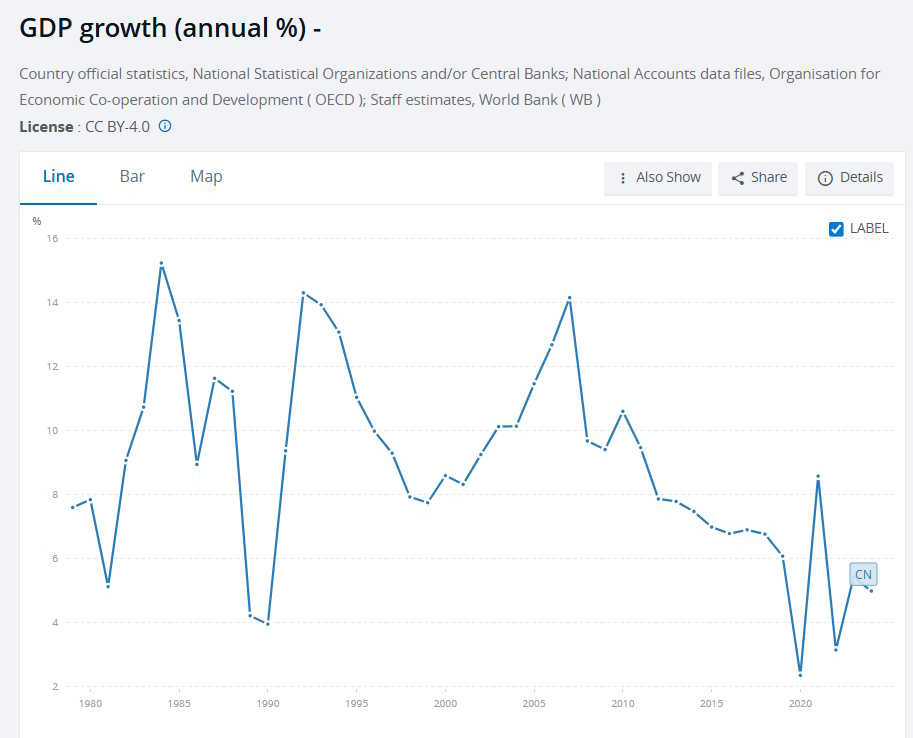

But this critique is overdone. Yes, it’s likely that India, like China, and like every other rapidly industrializing country, will experience a slowdown in growth as it gets richer. But growth could also accelerate for a while. China’s growth slowed in the 1990s, but then accelerated in the 2000s after it joined the WTO:

Growth is not always a smooth deceleration; sometimes it goes up for a while. And if Indian policy improves, it could see growth accelerate — or at least remain high as the country gets richer.

And India is still experimenting with policy reforms. Just the other day, it rolled out a major reform of its sclerotic labor laws:

India implemented overhauled labor laws that aim to attract investments and make it easier for companies to do business in the South Asian nation…The laws, grouped in four separate codes, replace archaic legislation and will give flexibility to companies to hire and fire workers, enhance safety standards and extend guaranteed social security benefits…

India’s maze of labor regulations, both at federal and state level, are considered to be rigid and complex, forcing companies to either remain small, employ fewer workers or use capital-intensive methods of production. The latest attempt is expected to make the rules uniform across the country[.]

Among other things, the new law allows women to work night shifts. This has the potential to help address India’s glaringly low female labor force participation rate. Most manufacturing miracles in history started with women migrating from farms to cities to work in labor-intensive light industry (garments, toys, electronics, etc.).1 If India manages to unlock this classic labor resource, it could not only give India a stronger manufacturing base, but also improve the country’s oddly low rate of urbanization.

I don’t mean to claim that this labor law reform will propel India to two decades of 7% growth. By itself, it won’t. But it shows that India’s government is able to push through pro-growth reforms over the objections of incumbent stakeholders. And it shows that the government cares enough about growth to do this.

There’s a theory out there, espoused by A.O. Hirschman back in the 1950s, that economic development creates political support for further development. Once the people of a country realize that rapid economic growth is possible, they may get used to the idea of their living standards increasing noticeably every year. On top of that, many elites become invested in the institutions of growth — owning construction companies, banks, and so on — and thus it’s in their interest for growth to continue.

Basically, this is the idea that Indians are not going to look back at two decades of fairly rapid growth — growth that has brought the country out of desperate poverty into lower-middle-income status — and conclude that this was enough. Instead, they may be willing to do the hard work of overruling vested interests — like the labor groups who resisted the recent labor law changes — in favor of reforms that promise to keep the economic party going.

Which other reforms would be key? For one thing, India needs to reform its financial system in order to help its companies scale up. The country currently has a very high cost of capital, meaning it’s hard for companies to borrow and grow. Fixing bond markets is one idea here, but most countries that experience economic growth “miracles” rely heavily on bank finance instead of on bond markets.

Beyond finance and harnessing rural women’s labor, there’s also probably a lot more India can do to boost their manufacturing sector. In a Noahpinion guest post this summer, Prakash Loungani and Karan Bhasin wrote down some ideas for how to do this:

In a nutshell, their suggestions are:

Repeal regulations that specifically stop large manufacturing companies from firing employees

Repeal local laws that make it hard to convert agricultural land to industrial use

Conduct more trade agreements, e.g. with Europe

Reduce red tape for manufacturers

This brings me to another reason I’m bullish on India is that there’s still a huge amount of room for manufacturing to grow. Right now, despite being the world’s fifth-largest manufacturer, India is still a service-intensive economy — manufacturing is only 13% of the country’s GDP. This has led some people to conclude that India just isn’t a country that can make things, and that they should stick to services. But recently there have been some hopeful signs for Indian industry.

For one thing, manufacturing has already been key to India’s rapid growth over the past few years. Menaka Doshi points out that “corporate investment announcements between April [and] September are at a decade high of 15.1 trillion rupees, led by manufacturing firms.” And India’s exports, especially of electronics, are rising:

India clocked the highest goods exports for November in 10 years. Two factors seem to have helped the country counter Trump’s 50% tariff. Buoyant electronics exports, of which Apple iPhones are expected to be the largest chunk. And export diversification, including to China…November trade data…shows India’s exports rose to $38.13 billion — up 19.4% from a year earlier, the biggest jump since June 2022…

Earlier this year, Apple expanded iPhone production in India to fulfill the majority of US demand.

Apple, the world’s best electronics company, is steadily moving more iPhone production to India. That shift, which has been happening since the pandemic, has been helping to drive an Indian electronics export boom:

The boom is still in its infancy, but this just gives it more room to grow. Right now, India’s electronics exports are mostly phones, but this just gives India the opportunity to expand into assembling computers and other electronics.

And while electronics assembly is the lowest part of the value chain, India may be climbing that ladder already. There are also reports that Apple is considering making some of the components of the iPhone in India as well:

Apple is in preliminary talks with some Indian chip manufacturers to assemble and package the component for the iPhone, said people with knowledge of the matter, a move that would mark a key step up in the value chain for vendors to the tech giant…It’s the first time Apple is evaluating the prospect of having certain chips assembled and packaged in India[.]

Components — mostly semiconductors of various sorts — represent the bulk of the value in an iPhone or other piece of modern electronics. Packaging and testing chips is a much higher-value activity than simply slapping components together into a final product.

In fact, India has recently focused on promoting the chip packaging and testing industry, often by soliciting foreign direct investment in the sector. This was how Malaysia became an electronics powerhouse, helping to propel that country to a GDP (PPP) of almost $44,000. It’s a very good strategy for India.

In any case, India just looks like a very promising growth story to me. The country has already been growing at a decently rapid clip, and its income levels are still low enough that it has lots of room to catch up with the technological frontier. It has shown that it still has the political will to push through major reforms, and its manufacturing sector is improving and has plenty of space to grow. It has a huge domestic market that will help its companies achieve scale. It has plenty of elite engineers and such. And due to its democracy and general friendliness, it’s looking like a more attractive production base than China for many multinational companies like Apple.

So what’s the bear case here? What are the key arguments that India can’t grow to become a comfortably upper-middle-income country over the next two decades?

One common idea, expressed by former Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, is that India will always be held back by internal fragmentation. Lee called India “not a real country”, “32 separate nations”, and “many nations along a British railway line”.

Linguistic fragmentation is certainly a challenge for India. But the country’s regions show no inclination to break away. And federalism can be a strength, too. There was an interesting story in The Economist recently comparing the economic growth models of Indian states Gujarat and Tamil Nadu. Gujarat has focused on building infrastructure, and has pursued capital-intensive industries like chemical manufacturing; Tamil Nadu has focused on improving education and health, and has pursued labor-intensive industries like electronics assembly.

But while The Economist pits these models against each other, the truth is that it’s probably good for a country to have both. A complex, diversified economy tends to grow faster than one that focuses on a single narrow range of industries. If India’s states find different paths to success, that could make the Indian economy more resilient in some ways than China, which is currently discovering the downsides of having a strong government that tells every province to make the same things.

Another bear case for India is the idea that China will throttle India’s rise. The reigning industrial powers of the 20th century — the U.S., Europe, Japan, and Korea — were remarkably nice to China during its early industrialization, cheerfully opening their markets to Chinese products and setting up joint ventures to teach Chinese people how to make anything and everything.

But China, the current reigning industrial power, is unlikely to be so nice to India. As expert China-watcher Rush Doshi explains, China’s current leadership wants to monopolize global manufacturing now and for all time. That explains why as Indian electronics manufacturing has ramped up, China has tried to block its engineers from going to India to train their replacements. I wrote a post about this back in March:

But I don’t believe this will cripple India’s growth model. China isn’t the only country that makes things; there are plenty of engineers from South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, the U.S., and Europe who can get Indians started making things. And as Xi Jinping’s regime continues to be repressive, and China’s growth continues to slow, lots of Chinese engineers will find ways to move to a country with more rapid growth and more personal freedom.

My guess is that the most important reason for widespread skepticism about India’s growth prospects is something that most people are too polite to say, except behind the shield of anonymity on a platform like X. A lot of people just don’t believe that Indians, as a people, have what it takes to build a modern high-tech economy. When I express optimism about India’s growth, someone always chimes in to say that Indians have low national IQ:

Let us set aside for a moment the question of whether national IQ studies are reliable. As the more circumspect of the two tweets above notes, cognitive ability and economic success are a two-way street. Though cognitive ability probably does boost growth, the reverse is also true — as countries get richer, they get better nutrition, more schooling, reduced pollution, and air conditioning, all of which contribute to better cognitive performance.

I view these discussions of IQ as a stand-in for something deeper — a suspicion that countries made up of people who aren’t of European or East Asian descent simply aren’t capable of building a wealthy, high-tech society. Although people of Indian descent have succeeded spectacularly in countries from the U.S. to Singapore to the UAE, no country in South Asia has reached upper-middle-income status — India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Bhutan are all still pretty poor. So because none of these countries has done it, a lot of people just assume that none of them can do it.

If you think about it, that assumption doesn’t make a lot of sense. Some country always has to be the first in its region to industrialize. Before Japan beat Russia in a war in 1905, Europeans didn’t think East Asian countries could become modern industrialized powers. And it wasn’t until the success of Japan’s auto and machinery industries in the 1970s that the world came to respect East Asian industrial prowess.

Nowadays, no one thinks it’s odd or unusual if an East Asian country gets rich; in fact, people suspect it. But there had to be a first country in the region to break old stereotypes and assumptions, and that country was Japan.

India is a much bigger country than Japan, which presents a challenge. It seems intuitively harder for a giant country like India to be the first in its region to break the old stereotypes and wow the world. But if you believe economists’ estimates, India is now about as rich a country as Japan was in 1962. The task is not insurmountable.

Call me crazy, but I think India can do it.

Updates

Commenter Jack Lowenstein writes:

As a long time India bull and former professional investor in listed equities there, I would add three points:

1) a positive byproduct of the high cost of capital is that ROEs are also high, and also that because debt capital is scarce, banks remain filters, not funnels. Nor does the Indian government coerce capital into SOEs.

2) fraud and corruption are often posited as negatives for the investment and growth story. However all though these are easy to find, I suggest India’s greater transparency compared to China, as made them less universal.

3) while many countries have great technical universities, I wonder if any have the level of competitive entry as the Indian Institutes of Technology. The nearest equivalent I can think of is French engineering schools.

(1) is an important point; at this early level of development, India needs to worry less about allocating resources and more about mobilizing resources.

(2) is interesting, because there’s some work claiming that China’s type of corruption — like America’s in the late 1800s — gave government officials an unofficial equity stake in development, and therefore encouraged development. It was “corruption”, but the kind of corruption that led to aligned incentives.

Meanwhile, India just passed another big reform package — this one about finance:

[L]awmakers passed a bill this week allowing up to 100% foreign ownership of insurance firms, bolstering an industry long viewed as under-penetrated and capital-starved. Regulators have also overhauled rules for banks, pension funds and capital markets as they aim to shift savings from idle assets such as gold and property toward equities, bonds and long-term investments to finance factories and infrastructure.

All these reforms come as Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his administration want to make India a developed economy by 2047, a goal that requires economic growth of about 8% per year[.]

I’m especially excited about the banking reform, whose goal is creating larger banks while also increasing the number of banks in the country. Of all the reforms in the package, this one seems the most likely to have a major impact.

Note the importance of growth targets in pushing through this reform. If India hadn’t grown at 8% in some recent years, it seems unlikely the government would feel confident in setting 8% as a growth target. This suggests that growth is creating expectations for further growth, which is creating momentum for policy reform.

My favorite book about this is Leslie Chang’s Factory Girls, which follows several of these women in China and chronicles the country’s growth through their eyes.

As a long time India bull and former professional investor in listed equities there, I would add three points:

1) a positive byproduct of the high cost of capital is that ROEs are also high, and also that because debt capital is scarce, banks remain filters, not funnels. Nor does the Indian government coerce capital into SOEs.

2) fraud and corruption are often posited as negatives for the investment and growth story. However all though these are easy to find, I suggest India’s greater transparency compared to China, as made them less universal.

3) while many countries have great technical universities, I wonder if any have the level of competitive entry as the Indian Institutes of Technology. The nearest equivalent I can think of is French engineering schools.

India has been so crippled by socialism that it has a huge runway to grow for decades. The recent labor reforms Noah cites are an example. Previously, firms with 100 or more employees needed government permission to lay off workers. The reforms increased this threshold to… 300. It’s like this everywhere you look, whether it’s high-level variables like urbanization and female labor force participation or low-level details like this layoff law. All that’s needed for them to grow is progressive unhobbling and there seems to be a lot of low hanging fruit to pick.