What can India do to industrialize?

A guest post by Prakash Loungani and Karan Bhasin.

I really believe that Indian industrialization is one of the most important stories in the world today. The fate of over a billion people — most of them still pretty poor — hinges crucially on the question of whether the world’s most populous nation can lift itself out of poverty by its bootstraps, as China has done, and as Vietnam is now in the process of doing.

Instead of writing another post about Indian industrialization, I thought I’d solicit a guest post from Karan Bhasin, who knows a lot about the subject. Karan is a doctoral candidate at University at Albany, SUNY, whose research has documented India’s recent progress in reducing poverty. He’s joined in this post by Prakash Loungani, the Director of the M.S. in Applied Economics program at Johns Hopkins University, who teaches a course on economic growth with Karan. Together, they explain the next steps they think India needs to take in order to supercharge its industrial development.

In February 2023, Noah posed an important question: can India industrialize? The question has been on the minds of Indian economic policymakers since its independence in 1947. Recent attempts at industrializing include Modi Government’s “Make in India” program and the liberal use of industrial policy for sectors such as electronics, semiconductors among others. However, the emphasis on industrial development is not new—India’s second Five-Year Plan in 1956 had already identified rapid industrialization as a key strategy for poverty alleviation.

In the 1950s, India had its own version of the Western Solow growth model—this was the P.C. Mahalanobis growth model, which emphasized the role of investment in capital goods (heavy industry) to drive long-term economic growth. It argued that a country should prioritize investment in industries that produce capital goods (like machinery and equipment) to increase its capacity to produce all types of goods, including consumer goods, in the future. The capital allocation decisions undertaken by India on the basis of the Mahalanobis Model yielded a growth rate of 4.3 percent, encouragingly close to the government’s target of 4.5 percent for 1956-61. This contributed to a growing sense of confidence in the ‘planned approach’ as an effective way to achieve industrialization. The confidence was, however, short-lived as growth started to falter during the Third Five-Year Plan. Indian policymakers started to recognize the need for reforms in their approach, particularly as many East Asian economies had successfully transformed their economies and were rapidly industrializing. These economies had embraced international trade, liberal domestic economy and limited the state to important areas such as rule of law, education and healthcare services etc. To emulate at the success of these “Miracle Economies” – Indian economic policymakers embarked on similar reforms in 1991. The objective behind these reforms was to fundamentally reorient the Indian economy from a planned economy to a market economy, hoping at such reforms would help India rapidly industrialize and move to a higher growth path.

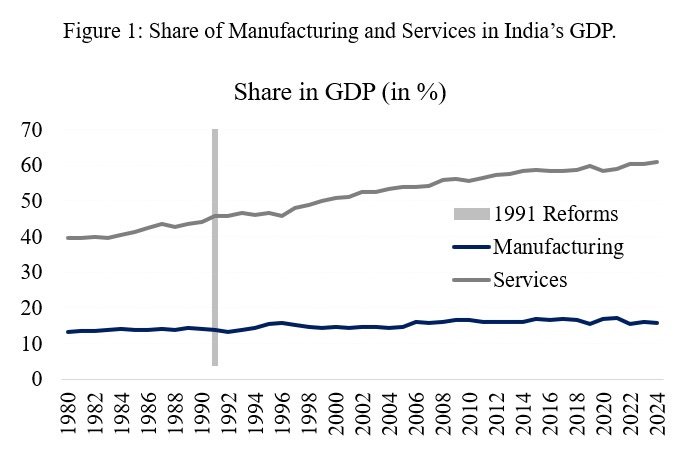

The 1991 reforms were successful in in many respects, but the success came with an Indian accent. Unlike East Asian peers, which first industrialized before pivoting towards services, India achieved success in export of high-value services even as it struggled with exports of labor-intensive products. Figure 1 illustrates that the share of manufacturing in India’s GDP has remained relatively flat, even as the services sector expanded significantly from 40% to 60% between 1980 and 2024. India is, therefore, paradoxically, a large labor-surplus economy which but struggles with labor-intensive production but instead specializes in production of high-value services (and also goods such as pharmaceuticals and more recently electronics).

Figure 1 presents the limited success at manufacturing even as it overshadows more recent successes following the Make in India push, particularly for electronics manufacturing. Smartphones, for instance are an example of great success with both Samsung and Apple shifting their production to facilities based out of India. Earlier this year, India shipped more smartphones to the US than China reflecting a significant milestone for the Indo-US relationship. While mobile phone production is capital-intensive rather than labor-intensive, this development underscores India’s potential to build a competitive industrial base when the right conditions are in place.

However, India’s lack of success at developing labor-intensive industries has not been due to lack of attempts or political will. To the contrary, India’s inability to achieve rapid industrialization has come despite a protracted policy attempts to do so under both planning and free market economic systems. It is therefore not surprising that in recent years, noted Indian economists Raghuram Rajan and Rohit Lamba have suggested that India “break the mold” and embrace services as an alternative source of employment.

To put things in context, let’s say that you visit a restaurant and order a Rasgulla – an Indian desert. The chef assembles all ingredients and prepares the desert but even with the right ingredients ends up with a Crème brûlée. Indian policymakers have been facing the same dilemma as they keep preparing the policy mix for manufacturing, only to find services outshine any success. It is therefore an important question on whether India’s struggles are due to the policy mix – or if there is inherently something that prevents manufacturing from taking off in a country with the world’s largest English-speaking college-educated workforce. Some have pointed at infrastructure or the lack of it as a major factor. However, in recent years India has been augmenting its physical infrastructure at an aggressive pace even as public spending in areas such as education or health has been lagging (see this article by Noah for more discussion of the same). In the remainder of this article, we highlight four barriers to manufacturing success.

1) Industrial regulations

India’s labor norms, particularly those relating to industry have imposed stringent conditions for retrenchment of workers, particularly for firms greater than 300 employees. These conditions were first introduced in the Industrial Disputes Act (1947) and have largely remained in place despite amendments to the Act.

These restrictions mean that that industrial units with more than 300 employees face higher regulatory restrictions on their ability to lay off workers, particularly during recessions. Firms in general respond to economic conditions by cutting back the length of the workweek and laying off workers, but the latter route is essentially prohibited for large manufacturing firms in India. It is well accepted that larger firms are more productive (Kochar et al, 2006). The IDA applied stringent labor regulations to registered companies that had attained a specific scale which meant that value-added was concentrated in unregistered firms.

Besley and Burgess (2004) exploited India’s regional heterogeneity to examine the question of labor regulation on economic growth and labor welfare. They studied labor regulations in various states and identified them as being either pro-worker or pro-employer. They found pro-worker regulations had an adverse effect on formal registrations of companies and encouraged informality in the economy. An important conclusion from their work was that such regulations did not materially contribute to promoting labor welfare or enhancing economic growth.

These results are important given that more recent labor reforms have continued to adopt policies that impose restrictions primarily on large firms with regards to their ability to adjust their workforce in response to economic conditions. This is more so for industries with thin margins, who are unlikely to be able to absorb business-cycle shocks. Their inability to adjust wage costs has meant either they have to stay small or rely on third-party contractors for their workers. In both cases, there are limited benefits from economies of scale as the policy imposes a severe penalty for achieving success and encourages firms to remain small in terms of their overall size. These policies also provide a good explanation for why firms have preferred to specialize in capital- intensive manufacturing – in a labor abundant but capital scarce developing economy.

These regulations do not apply to service-based firms, which has therefore allowed such firms to increase in size and benefit from economies of scale. Perhaps, an important policy that can help India’s industrialization efforts would be to do away with such regulations and allow for more dynamic adjustments in the labor market. This would indeed subject workers at big industrial units to business-cycle fluctuations – but an alternative way to insure against such risks would be to devise an unemployment insurance-based social protection policy, as recommended by Duval and Loungani (2019).

2) Land Acquisition Hurdles

As in the case of labor, similar laws have restricted the shift of land—the other important factor of production -- from agriculture to other purposes. Conversion of land from agriculture to industry has remained as a challenge in many Indian states. The lack of adequate land for industry has meant much higher cost of land acquisition which locks in a considerable amount of capital for firms. To be fair, there was an attempt at reforming these laws in 2015, but political opposition thwarted the effort. Some states have since then worked on resolving these challenges at their own level. States that have adequate land available for industry have gradually benefitted as they have succeeded in attracting greater investments.

3) Ambivalence about International Trade

A common feature of East Asian economies was that they embraced international trade and allowed for a free exchange of goods and services. This allowed many of these economies to tap into export markets and specialize in specific sectors to rapidly industrialize. Export markets allowed firms to scale in size and the benefits spilled over to other sectors of these economies.

India’s economic history – particularly for the first three decades focused on restricting international trade through a policy of licenses and export controls. Unlike export-oriented growth strategies, India embraced what was known as import substitution. Early planners had prioritized capital allocation to sectors that witnessed extensive imports. Liberalization in 1991 reversed the trend but not entirely. The process of reduction of tariffs continued well through the early 2000s. Incidentally, India’s high growth years coincided with high growth in global trade and in general a period of reduction of tariffs. There was a brief reversal in mid 2010s as India gradually began to increase duties. The process continued as industry argued for protection against cheaper imports and there was a reluctance on part of policymakers to embrace bilateral free trade agreements or enter trading blocks.

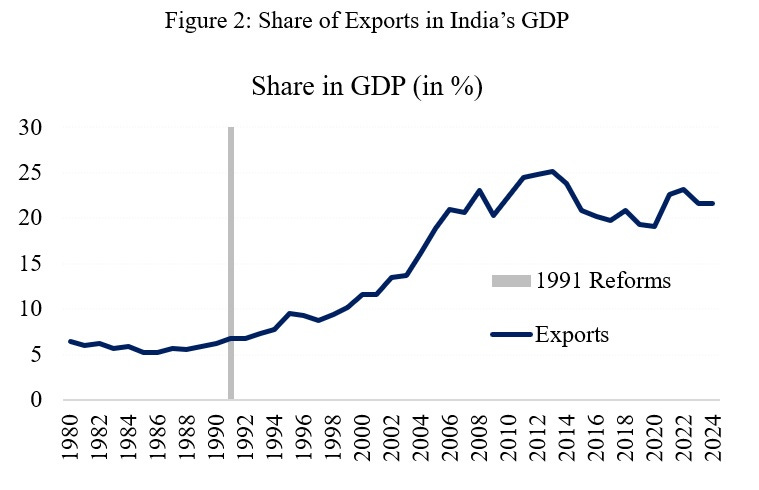

All this while, India’s export of services has grown exponentially. Figure 2 illustrates the steady rise in the share of exports in India’s GDP since the 1991 reforms. Moreover, as highlighted by Noah, India’s overall exports of goods and services in terms of GDP are of the same magnitude as that of China. Even for manufacturing, the sectors that have performed well have been those that focused on export markets and were subjected to greater competition. Subjecting the overall economy to greater competition and ensuring lower duties on critical raw materials will be of essence in allowing India to integrate with existing supply chains. The recent trade agreement with the UK is therefore an important development even as a similar agreement is being negotiated with the EU and the US. Prioritizing a trade agreement with the U.S. is particularly important to eliminate tariff-related uncertainty and strengthen the economic partnership between the world’s largest and oldest democracies. Notably, many of India’s competitors already benefit from preferential trade agreements with the U.S., resulting in lower tariffs compared to the 25% currently levied on Indian exports.

4) (lack of) ease of doing business

India’s historically hostile business investment is legendary. Investors have often compared the ease of business in East Asia with the lack of it in India. There has been considerable progress over the last decade with single-window clearances and a top-down push to make India more attractive. Different states have tried to adopt a digital-only system for permissions to restrict corruption. Things have gradually moved in the right direction.

Despite these measures, there private sector investments have been lagging. India’s top economic policymaker, Nirmala Sitharaman has repeatedly pointed at the lack of private investment by Indian industrialists even as the government appears to have delivered on their Wishlist, particularly in terms of a lower corporate tax or lower interest rates. Raghuram Rajan too has reflected on the unwillingness of private sector to invest.

We point at certain disturbing trends with regards to business regulation. The first is the withdrawal from Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs). These treaties allowed for dispute resolution in a third-party country – presumably one with a more efficient and well-functioning judiciary. Foreign investors would likely require such protection given the large numbers of pending cases across different levels of Indian judiciary. A direct effect of the decision to withdraw from BITs means lowers Foreign Direct Investment flowing into India. Combined with the pivot towards protectionism, it has meant lesser need for urgent capital allocation by firms – many of which have witnessed record profits and sit on healthy balance sheets. Luckily, there has been some re-think on BITs and on international trade, which would address this issue.

The second issue pertains to the issue of cost of compliance for Indian firms which has increased over the last few years. Stringent Know Your Customer norms (KYC) to remove anonymity of money have been introduced as a part of anti-corruption measure. Statutory powers of agencies that investigate economic crimes and tax authorities have expanded to restrict tax evasion. These measures, while important, can often lead to an assault on individual rights particularly in a system where grievance redressal would be delayed in a clogged judiciary. There is a need to reassess and reevaluate these powers given the prospects of their misuse. India’s investors, even if willing to invest might be reluctant given the regulatory landscape.

Regional Heterogeneity

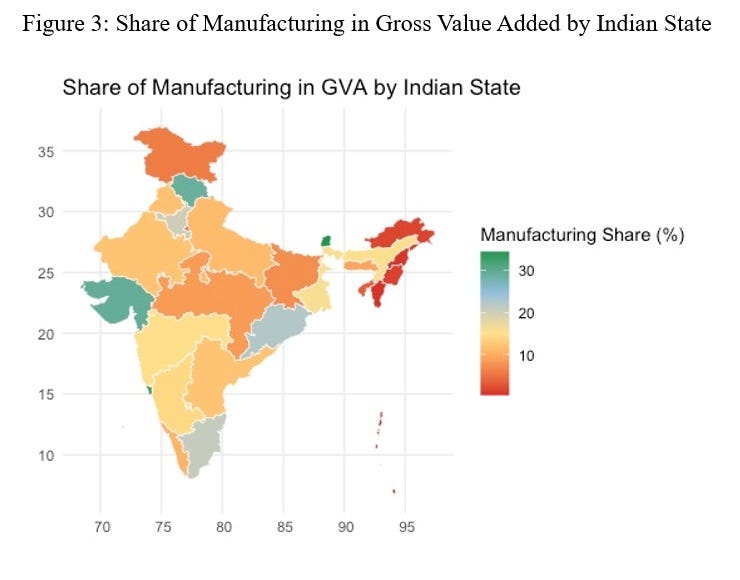

These barriers may appear insurmountable but that is not the case as some states have been more successful than others in industrializing. As reflected by Rodrik and Subramanian (2004), effective competition among states to attract domestic and foreign capital led to a ‘race to the top’. In Figure 3, we highlight the share of manufacturing in the Gross Value Added (GVA) for Indian states. The peninsular states have a significantly higher share of industrial output relative to the hinterlands. Access to ports is a natural advantage in many of these states but many of them have in addition undertaken several reforms governing their factor markets such as land and labor laws. The apparent success of some of these states illustrates an important reality of the Indian economy: that is, the indispensable nature of State Governments in India’s attempt to rapidly industrialize.

At the federal level, undertaking critical factor market reforms that allow for greater dynamism, ensuring access to export markets and improving ease-of-doing business are necessary but may not be sufficient for India to industrialize. Bulk of the reforms and heavy lifting has to be undertaken at the local level, and this realization is gradually seeping in. Tamil Nadu and Gujarat, for instance has emerged as a major player in India’s automobile manufacturing value chain. Both these states, along with Andhra Pradesh are now aggressively wooing electronics and semiconductor firms to establish their manufacturing plans in their respective states. Granted that some of these industries are again capital intensive – but it illustrates the broader point that India can industrialize, if only the state gets out of the way. Perhaps the best ‘masala mix’ to achieve a successful manufacturing base would be to let the state treat manufacturing just as services: that is, to just let them be.

References:

Besley, T., & Burgess, R. (2004). Can labor regulation hinder economic performance? Evidence from India. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(1), 91-134.

Duval, M. R. A., & Loungani, M. P. (2019). Designing Labor Market Institutions in Emerging and Developing Economies: Evidence and Policy Options. IMF Staff Discussion Notes, (2019/004).

Kochhar, K., Kumar, U., Rajan, R., Subramanian, A., & Tokatlidis, I. (2006). India's pattern of development: What happened, what follows?. Journal of Monetary Economics, 53(5), 981-1019.

Rodrik, D., & Subramanian, A. (2004). Why India can grow at 7 per cent a year or more: projections and reflections. Economic and Political Weekly, 1591-1596.

My experience may be of interest. After working with brilliant Indian teams (programmers and statisticians) in a previous career, I decided to make in India the steel assemblies for a new product that I have invented. I mean, India has made steel for 2,000 years, right? It's a relatively simple product, without electronics, but brand new.

We are working with a factory partner in Rajkot. Clearly infrastructure is an issue for them, since the roads can become impassible due to weather and electricity shortages shuts the factory down (involuntarily) one day a week.

While I appreciate the contribution of academic economists (I went to school with Dani Rodrik, after all), I see some cultural issues that may hold some importance as well. These, in my experience, are sometimes a blind spot for economists.

I conjecture that some of these issues are rooted in India's history of exploitative colonialization as well as other differences from Asia, including a very hierarchical social structure.

Stop Being So Polite. My factory partners are deferential in ways, as an American, I don't need. They seem unwilling to bring me bad news that my team and I need in order to work with them effectively to solve fabrication problems. It sometimes feels like a lack of trust, but it may just be rooted in an expectation of hierarchy and arbitrary decision-making. Guys, please just focus on meeting my business needs, not my emotional needs. We're looking for win-win, not to exploit you.

Embrace Innovation. It was genuinely a surprise to my partners that I wasn't just sending them a product to copy more cheaply. This is a new product and all we've got are plans and a rough prototype. At least in the Indian steel industry, the logic of innovation seems less prevalent. When they innovate, we both win, but I'm not sure they believe that.

Orient toward Quality. My understanding is that in Japanese, the verb for "to study" is roughly "to copy" (I could be wrong). It's telling that the Indian government and business community embraced tariffs that protected shoddy domestic manufacture. Apparently, the quality was "good enough" for the masses. I don't think our partner really understood that we were serious about quality until I showed them our colorimeter, micrometer, and paint depth measuring devices we use to inspect their work product, even factory samples. We constantly are asking them to prioritize quality. In my experience, factories in Asia will proudly show off their state of the art QC.

Risk Aversion. This is something I admit to really not understanding, but it was a long search to find the right factory partner who wanted to go on this journey with us. They won't make a lot of money unless the product is a success and we scale production up together. I suspect there is a big cultural difference in risk aversion to working with a startup, even a US one.

Government can help or hurt, but I don't believe there's some magic government policy rooted in economic models that will enable India's industrial base to grow smoothly and without risk or occasional retrenchment. Rather, I hope they try more pragmatic flexible experiments, tailored to each region's strength.

I'm optimistic about our collaboration with the Indian factory, and I believe we'll product a great product together. However, I've tried to be clear-eyed about the constraints and challenges we both face, both overt and implicit.

Good piece. India has a tremendous opportunity given it hasn’t yet been hit by the wave of demographic decline washing over most of the rest of Asia (and Europe and the Americas).

The educational system is good at the secondary and tertiary levels and more tech focused than most of Europe, Africa and Latam, so human capital (whether in number or quality) should not be a constraint.

Unfortunately, India has long been run by an anti-competitive, quasi-socialistic mindset at the top and plagued by a corrupt, rent-seeking bureaucracy at the bottom (sounds like a blue state, or maybe Italy!), has poor infrastructure and has a low trust culture that seems somewhat unethical or immoral to outsiders (also Italy). Essentially, the supply side is a mess, infrastructure is a mess, and rule of law (in practice) is a problem.

That being said, there is an entrepreneurial and commercial spirit (a bit like Italy, in some of that is directed toward theft, corruption, gaming the system, etc) though a pretty big divide between the industrialized/modern sectors and pockets of subsistence living.

Democracy is well-established even if honesty, clarity and rule of law is not.

I like their chances. If they can deregulate, educate, build infrastructure and improve rule of law they would be wildly successful. Same might be said of Nigeria, Brazil, Egypt, Iran. Problem is those payoffs are long-term and politicians aren’t benevolent seers (more likely to be rent-seekers and skimmers like Lula, most African leaders) or more focused on suppressing internal/sectarian dissent (or are both authoritarians and skimmers).