I love AI. Why doesn't everyone?

Anti-AI sentiment might or might not be rational, but it certainly relies on a lot of bad arguments.

New technologies almost always create lots of problems and challenges for our society. The invention of farming caused local overpopulation. Industrial technology caused pollution. Nuclear technology enabled superweapons capable of destroying civilization. New media technologies arguably cause social unrest and turmoil whenever they’re introduced.

And yet how many of these technologies can you honestly say you wish were never invented? Some people romanticize hunter-gatherers and medieval peasants, but I don’t see many of them rushing to go live those lifestyles. I myself buy into the argument that smartphone-enabled social media is largely responsible for a variety of modern social ills, but I’ve always maintained that eventually, our social institutions will evolve in ways that minimize the harms and enhance the benefits. In general, when we look at the past, we understand that technology has almost always made things better for humanity, especially over the long haul.

But when we think about the technologies now being invented, we often forget this lesson — or at least, many of us do. In the U.S., there have recently been movements against mRNA vaccines, electric cars, self-driving cars, smartphones, social media, nuclear power, and solar and wind power, with varying degrees of success.

The difference between our views of old and new technologies isn’t necessarily irrational. Old technologies present less risk — we basically know what effect they’ll have on society as a whole, and on our own personal economic opportunities. New technologies are disruptive in ways we can’t predict, and it makes sense to be worried about that risk that we might personally end up on the losing end of the upcoming social and economic changes.

But that still doesn’t explain changes in our attitudes toward technology over time. Americans largely embraced the internet, the computer, the TV, air travel, the automobile, and industrial automation. And risk doesn’t explain all of the differences in attitudes among countries.

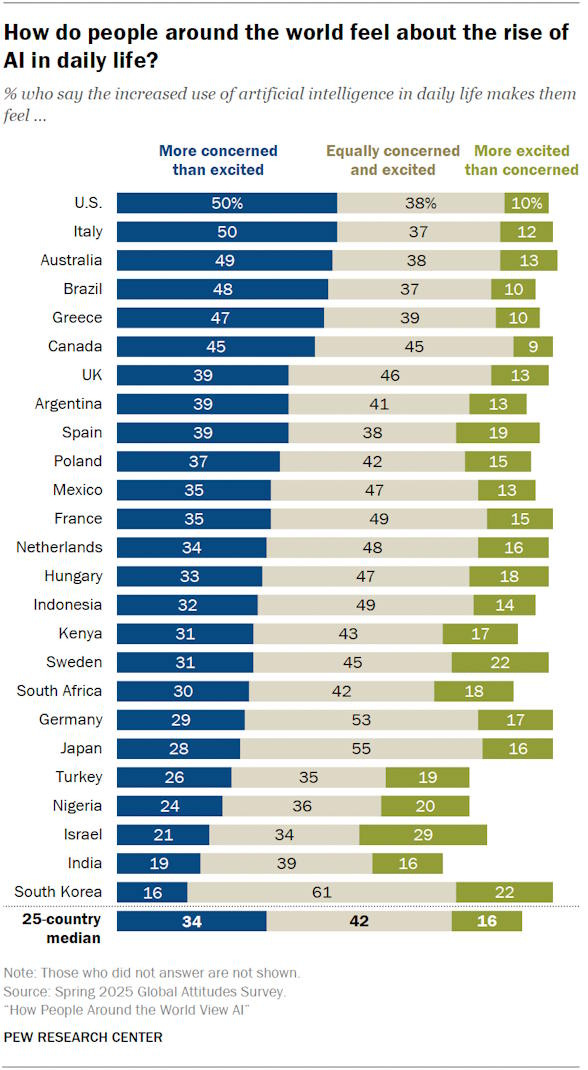

In the U.S., few technologies have been on the receiving end of as much popular fear and hatred as generative AI. Although policymakers have remained staunchly in favor of the technology — probably because it’s supporting the stock market and the economy — regular Americans of both parties tend to say they’re more concerned than excited, with an especially rapid increase in negative sentiment among progressives.

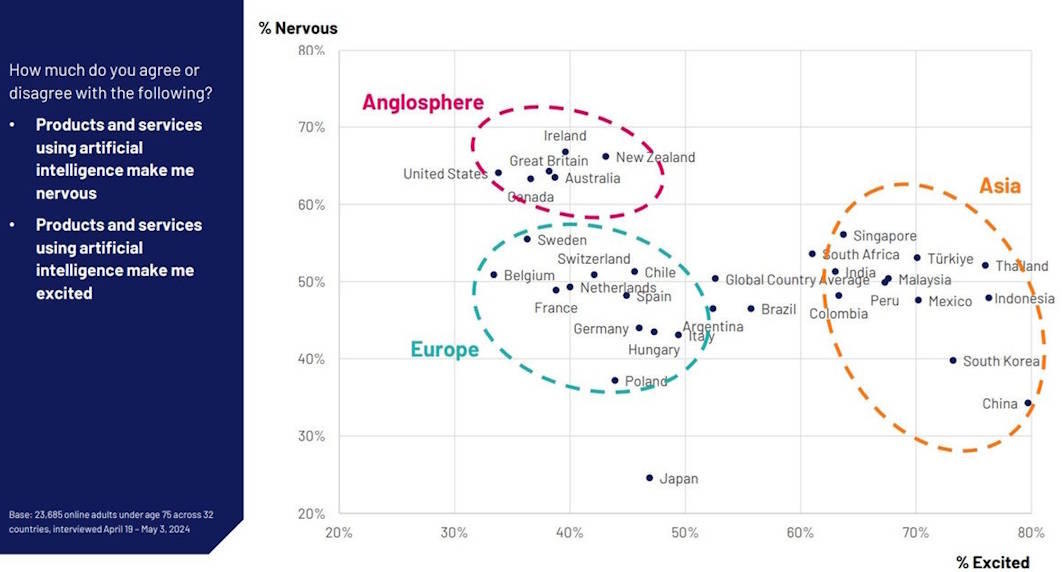

There is plenty of trepidation about AI around the world, but America stands out. A 2024 Ipsos poll found that no country surveyed was both more nervous and less excited about AI than the United States:

America’s fear of AI stands in stark contrast to countries in Asia, from developing countries like India and Indonesia to rich countries like South Korea and Singapore. Even Europe, traditionally not thought of as a place that embraces the new, is significantly less terrified than the U.S. Other polls find similar results:

If Koreans, Indians, Israelis, and Chinese people aren’t terrified of AI, why should Americans be so scared — especially when we usually embraced previous technologies wholeheartedly? Do we know something they don’t? Or are we just biased by some combination of political unrest, social division, wealthy entitlement, and disconnection from physical industry?

It’s especially dismaying because I’ve spent most of my life dreaming of having something like modern AI. And now that it’s here, I (mostly) love it.

I always wanted a little robot friend, and now I have one

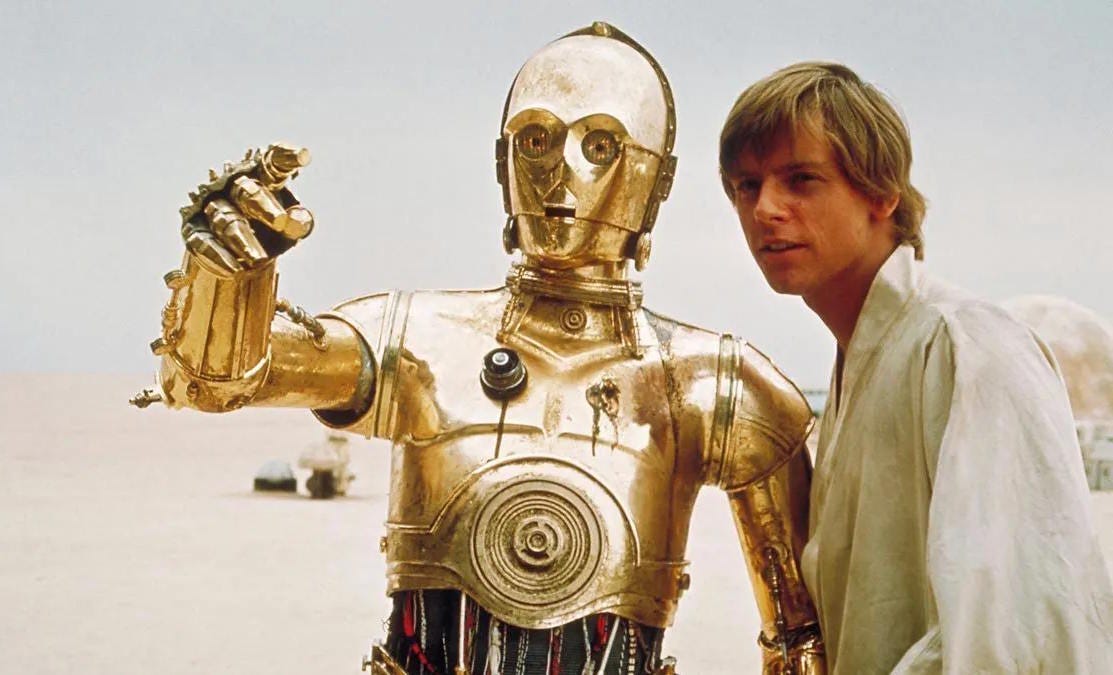

Media has prepared me all my life for AI. Some of the portrayals were negative, of course — Skynet, the computer in the Terminator series, tries to wipe out humanity, and HAL 9000 in 2001: A Space Odyssey tries to kill its user. But most of the AIs depicted in sci-fi were friendly — if often imperfect — robots and computers.

C-3PO and R2-D2 from Star Wars are Luke’s loyal companions, and save the Rebellion on numerous occasions — even if C-3PO is often wrong about things. The ship’s computer in Star Trek is a helpful, reassuring presence, even if it occasionally messes up its holographic creations.1 Commander Data from Star Trek: The Next Generation is a heroic figure, probably based on a character from Isaac Asimov’s Robot series — and is just one of hundreds of sympathetic portrayals of androids. Friendly little rolling robots like Wall-E and Johnny 5 from Short Circuit are practically a stock character, and helpful sentient computers are important protagonists in The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, the Culture novels, the TV show Person of Interest, and so on. The novel The Diamond Age features an AI tutor that helps kids out of poverty, while the Murderbot series is about a security robot who just wants to live in peace.

In these portrayals, intelligent robots and computers are consistently portrayed as helpful assistants, allies, and even friends. Their helpfulness makes sense, since they’re created to be our tools. But some deep empathetic instinct in our human nature makes it difficult to objectify something so intelligent-seeming as a simple tool. And so it’s natural for us to portray AIs as friends.

Fast forward a few decades, and I actually have that little robot friend I always dreamed of. It’s not exactly like any of the AI portrayals from sci-fi, but it’s recognizably similar. As I go through my daily life, GPT (or Gemini, or Claude) is always there to help me. If my water filter needs to be replaced, I can ask my robot friend how to do it. If I forget which sociologist claimed that economic growth creates the institutional momentum for further growth,2 I can ask my robot friend who that was. If I want to know some iconic Paris selfie spots, it can tell me. If I can’t remember the article I read about China’s innovation ecosystem last year, my robot buddy can find it for me.

It can proofread my blog posts, be my search engine, help me decorate my room, translate other languages for me, teach me math, explain tax documents, and so on. This is just the beginning of what AI can do, of course. It’s possibly the most general-purpose technology ever invented, since its basic function is to memorize the entire corpus of human knowledge and then spit any piece of it back to you on command. And because it’s programmed to do everything with a smile, it’s always friendly and cheerful — just like a little robot friend ought to be.

No, AI doesn’t always get everything right. It makes mistakes fairly regularly. But I never expected engineers to be able to create some kind of infallible god-oracle that knows every truth in the Universe. C-3PO gets stuff confidently wrong all the time, as does the computer on Star Trek. For that matter, so does my dad. So does every human being I’ve ever met, and every news website I’ve ever read, and every social media account I’ve ever followed. Just like with every other source of information and assistance you’ve ever encountered in your life, AI needs to be cross-checked before you can believe 100% in whatever it tells you. Infallible omniscience is still beyond the reach of modern engineering.

Who cares? This is an amazingly useful technology, and I love using it. It has opened my informational horizons by almost as much as the internet itself, and made my life far more convenient. Even without the expected impacts on productivity, innovation, and so on, just having this little robot friend would be enough for me to say that AI has improved my life enormously.

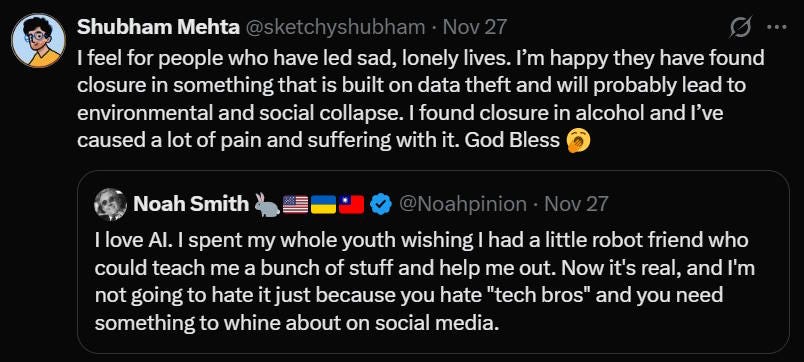

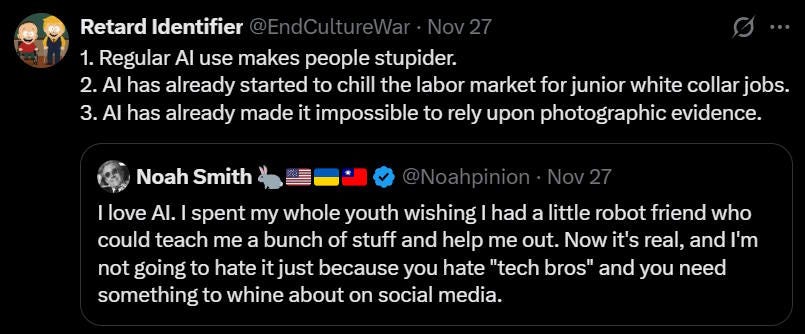

This instinctive, automatic reaction to such a magical new tool seems utterly natural to me. And yet when I say this on social media, people pop out of the woodwork to denounce AI and ridicule anyone who likes it. Here are just a few examples:

Normally I would just dismiss these outbursts as non-representative. But in this case, there’s pretty robust survey data showing that the American public is overwhelmingly negative on AI. These social media malcontents may be unusually vituperative, but their opinions probably aren’t out of the mainstream.

What’s going on here? Why doesn’t everyone else love having a little robot friend who can answer lots of their questions and perform lots of their menial tasks?

I guess it makes sense that for a lot of people, the potential negative externalities — deepfakes, the decline of critical thinking, ubiquitous slop, or the risk that bad actors will be able to use AI to do major violence — loom large. Other people, like artists or translators, may fear for their careers. I think it’s likely that in the long run, our society will learn to deal with all those challenges, but as Keynes said, “in the long run we’re all dead.”

And yet the instinctive negativity with which AI is being met by a large segment of the American public feels like an unreasonable reaction to me. Although externalities and distributional disruptions certainly exist, the specific concerns that many of AI’s most strident critics cite are often nonsensical.

A lot of the anti-AI canon is nonsense

One of the most common talking points you hear about AI is that data centers use a ton of water, potentially causing water shortages. For example, Rolling Stone recently put out an article by Sean Patrick Cooper, entitled “The Precedent Is Flint: How Oregon’s Data Center Boom Is Supercharging a Water Crisis”. Here’s what it claimed:

[D]ata centers pose a variety of climate and environmental problems, including their impact on the water supply. The volume of water needed to cool the servers in data centers — most of which need to be kept at 70 to 80 degrees to run effectively — has become a nationwide water resource issue particularly in areas facing water scarcity across the West. This year, a Bloomberg News analysis found that roughly “two-thirds of new data centers built or in development since 2022 are in places already gripped by high levels of water stress.” Droughts have plagued Morrow County, occurring annually since 2020. But even areas with ample water reserves are vulnerable to the outsized demand from data centers. Earlier this year, the International Energy Agency reported that data centers could consume 1,200 billion liters by 2030 worldwide, nearly double the 560 billion liters of water they use currently.

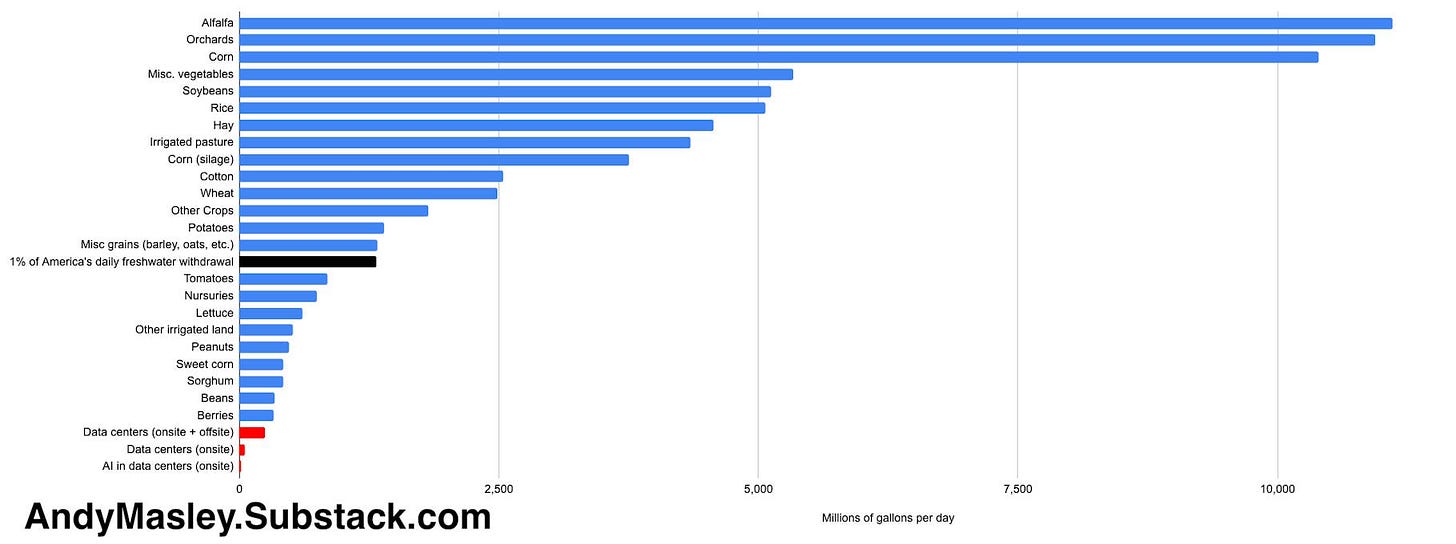

The idea that AI data centers are water-guzzlers has become standard canon in many areas of the internet — especially among progressives. And yet it’s just not a real issue. Andy Masley finally got fed up and dug into the data, writing an epic blog post that debunked every single version of the “AI uses lots of water” narrative:

Masley notes that A) almost all of the water AI uses is actually used by power plants generating electricity to power AI, and B) most of the water that gets “used” by AI is actually just run through the system and returned to the original source, instead of being used up. He writes:

So of the ways AI uses water…The vast majority (maybe 90%) is withdrawn, freshwater (not potable) that is indirectly (offsite) used non-consumptively in power plants (it’s returned to the source unaffected)…Less (maybe 7%) is withdrawn freshwater (not potable) that is consumed (evaporated) indirectly (offsite) in the power plants to generate the electricity AI uses…And less (maybe 3%) is withdrawn freshwater that’s then treated to become potable, used directly (onsite) in physical data centers themselves, and consumed after (not returned to the source, evaporated).

He then goes on to pull a bunch of numbers that show that AI’s actual water consumption isn’t a problem (yet):

All U.S. data centers (which mostly support the internet, not AI) used 200–250 million gallons of freshwater daily in 2023. The U.S. consumes approximately 132 billion gallons of freshwater daily…So data centers in the U.S. consumed approximately 0.2% of the nation’s freshwater in 2023…However, the water that was actually used onsite in data centers was only 50 million gallons per day…Only 0.04% of America’s freshwater in 2023 was consumed inside data centers themselves. This is 3% of the water consumed by the American golf industry.

AI uses approximately 20% of the electricity in data centers…Water use roughly correlates with electricity…So AI consumes approximately 0.04% of America’s freshwater if you include onsite and offsite use, and only 0.008% if you include just the water in data centers. So AI…is using 0.008% of America’s total freshwater…

So the water all American data centers will consume onsite in 2030 is equivalent to:

8% of the water currently consumed by the U.S. golf industry.

The water usage of 260 square miles of irrigated corn farms, equivalent to 1% of America’s total irrigated corn.

And he includes a chart for comparison to other water uses:

He goes on to debunk other aspects of the “AI water use” story, showing that data centers haven’t hurt water availability in local areas, and that data centers aren’t a major source of pollution. After that, he goes through some articles claiming a link between AI and water use, and finds that either their data is obviously wrong, or they don’t even cite data.

Masley is especially annoyed with a book by Karen Hao called Empire of AI, which made huge math errors about AI water use:

Within 20 pages, Hao manages to:

Claim that a data center is using 1000x as much water as a city of 88,000 people, where it’s actually using about 0.22x as much water as the city, and only 3% of the municipal water system the city relies on. She’s off by a factor of 4500.

Imply that AI data centers will consume 1.7 trillion gallons of drinkable water by 2027, while the study she’s pulling from says that only 3% of that will be drinkable water, and 90% will not be consumed, and instead returned to the source unaffected.

Paint a picture of AI data centers harming water access in America, where they don’t seem to have caused any harm at all.

Hao later admitted some serious data errors in her book.

Anyway, Masley’s whole post is very long and involved, and it links to a bunch of other long and involved posts on the various subtopics. If you’re interested in the “AI water use” issue at all, this is a must-read. I’m not sure I’ve ever seen so thorough a debunking of a popular belief. Some AI critics like Timnit Gebru attacked Masley, but were not able to muster any substantive rebuttal; instead, they simply suggested that Masley speak to activists:

There are two things that are especially frustrating about the “AI and water use” argument. First, there’s the powerlessness of facts in the face of viral misinformation. If a bogus claim gets repeated by enough people, it becomes its own sort of echo chamber, where observers believe the false claim because they think they’ve heard it from multiple sources. Politically motivated reasoning only adds to that effect — a lot of Americans fear AI and want to find a reason why it’s bad, so they latch onto the “water use” story without checking to see if it’s real.

The second frustrating thing is that there’s a much better argument sitting right there for the taking. AI doesn’t use up much water, and probably won’t for the foreseeable future. But it does use a hell of a lot of electricity, and this could pose a problem if the tech keeps scaling up. That electricity use can strain local grids and raise carbon emissions. It’s a real challenge! And yet AI critics tend to ignore this grounded and reasonable worry in favor of the “water use” myth.

Nor is this the only such example. Aaron Regunberg, writing in The New Republic, trots out a vast litany of accusations against AI, most of which don’t hold up under scrutiny. For example, he claims that an AI crash would wipe out normal Americans while preserving the wealth of AI’s creators:

First, there is the likelihood that the AI industry is building up a bubble that, when it bursts, will take down the global economy…When this thing pops, it won’t be the filthy rich scammers behind the bubble who will lose out. It will be regular people: One former International Monetary Fund chief economist estimates that a crash could wipe out $20 trillion in wealth held by American households.

But that’s absurd. Gita Gopinath’s analysis, which Regunberg cites, is all about stock wealth. Most of the wealth of the people who create AI is in their own company’s stocks, so they would absolutely get wiped out in a crash. Regular Americans would get hurt a bit, but most of their wealth is in their houses. Almost all American stocks are owned by the rich. In fact, there was a tech stock crash in 2022, and wealth inequality went down as a result.

Anyway, Regunberg continues:

Beyond the profoundly compelling politics of a market crash and bailout, there’s the equally potent issue of AI-driven job losses. These hits have already begun. Last summer, IBM replaced hundreds of employees with AI chatbots, and UPS, JPMorgan Chase, and Wendy’s have all begun following suit. The CEO of Anthropic has warned that AI could lead to the loss of half of all entry-level white-collar jobs; McKinsey estimated that AI could automate 60 to 70 percent of employees’ work activities; and a recent report from Senator Bernie Sanders and the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee found that AI could replace 89 percent of fast-food and counter workers, 64 percent of accountants, and 47 percent of truck drivers. The anger that such dislocations will generate against “clankers”—yes, anti-AI frustration has already inspired the explosion of a Gen Z meme-slur—is hard to overstate, potentially exceeding the resentment against the North America Free Trade Agreement that Trump rode to the White House in 2016.

The studies Regunberg cites, predicting how many jobs will be “replaced”, actually say no such thing, as I explained in this post back in 2023:

They are merely engineers’ guesses about which jobs will be affected by AI.

In fact, one recent study found that industries that are predicted to use AI more are seeing no slowdown in wages, and have experienced robust employment growth for workers in their 30s, 40s, and 50s:

The study did find a slowdown in hiring for younger workers. But other studies find no effect of AI on jobs at all so far. Obviously, many workers are afraid of losing their jobs to AI, but those losses don’t seem to have materialized yet, so it’s a bit silly when AI critics like Regunberg present job losses as established fact.

How can folks like Regunberg, Gebru, Hao, and Cooper get away with such incredible sloppiness? Unfortunately, the answer is “motivated reasoning”. So many Americans feel so negatively about AI that if some writer or intellectual comes up and makes some claim that AI is a water-guzzler or is causing mass unemployment, some people will believe it. Fear and anger have a way of finding their own justifications.

So I don’t think there’s much I can do about the unreasonable negative emotions being directed at AI in the United States. I’ve simply got to reconcile myself to the fact that my delight in this new technology is a rare minority position. I do think there are probably some things that AI companies can do to improve their image with the American public. But for now, all I can do is lament that a country that once boldly embraced the future now quails at it.

In fact, I’d argue that the Star Trek computer is the sci-fi portrayal of AI that most accurately predicts modern generative AI. Whole plots of Star Trek: The Next Generation revolve around holodeck prompts that generate hallucinations.

A.O. Hirshman

The droids in star wars are literal slaves. Like that is their purpose. We meet R2D2 and C3P0 when they are sold by the jawas to Luke's uncle.

I am being a bit facetious here, but not pointing that out in the post seems like an oversight.

Also, this post complains the most about the false belief in water loss from AI. There are many better things to complain about vis a vis AI, but the post hides behind the water thing to avoid having to go into depth about the others.

I don’t hate AI. I do hate that companies, mine included, are giving mandates to incorporate it into work without actually thinking it through. I hate the tech bro hype surrounding it. I hate the capital class will try and use it to immiserate everyone else to increase their wealth.

If it crashed and took all of their wealth and knocked tech bros down several pegs, I’d crack a smile to be honest.