AI and jobs, again

Some top economists claim AI is now destroying jobs for a subset of Americans. Are they right?

The debate over whether AI is taking people’s jobs may or may not last forever. If AI takes a lot of people’s jobs, the debate will end because one side will have clearly won. But if AI doesn’t take a lot of people’s jobs, then the debate will never be resolved, because there will be a bunch of people who will still go around saying that it’s about to take everyone’s job. Sometimes those people will find some subset of workers whose employment prospects are looking weaker than others, and claim that this is the beginning of the great AI job destruction wave. And who will be able to prove them wrong?

In other words, the good scenario for the labor market is that we continue to exist in a perpetual state of anxiety about whether or not we’re all about to be made obsolete by the next generation of robots and chatbots.

The most recent debate about AI and jobs centers around recent college graduates. Derek Thompson wrote a post suggesting that a slowdown in job-finding for recent college grads could be the first sign of the job-pocalypse. A number of news articles ran with this story and treated AI job destruction as a proven fact, but some pundits pushed back on the narrative, citing various data sources. I wrote about the whole controversy in this post:

Then, Sarah Eckhardt and Nathan Goldschlag of the Economic Innovation Group, a think tank, came out with some research that found no detectable effect of AI on recent employment trends. (I covered this research in my last roundup post.)

Eckhardt and Goldschlag looked at several measures of which jobs are more “exposed to” AI. They found that for three of the five exposure measures they looked at — including their preferred measure, from Felten (2021) — there was no detectable difference in unemployment between the more exposed and the less exposed workers. But for two of the measures, there was a small difference, on the order of 0.2 or 0.3 percentage points:

The EIG researchers conclude that AI probably isn’t taking jobs yet, and if it is, the effect is still very small at this point.

Eckhardt and Goldschlag were wise to title their research note “AI and Jobs: The Final Word (Until the Next One)”. Indeed, the next word on the topic came out almost immediately, in the form of a paper by Brynjolfsson, Chandar, and Chen, entitled “Canaries in the Coal Mine? Six Facts about the Recent Employment Effects of Artificial Intelligence”.

Brynjolfsson et al. do something very similar to Eckhardt and Goldschlag — they use two measures of how exposed a job is to AI, and then they compare recent employment trends for more and less exposed workers. Their finding is startlingly different than that of the EIG team:

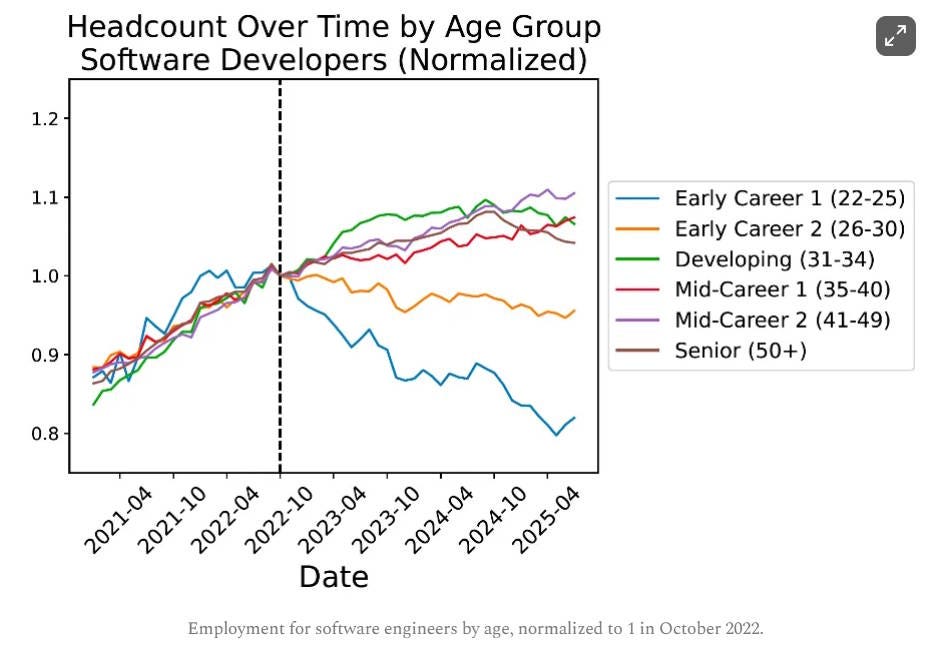

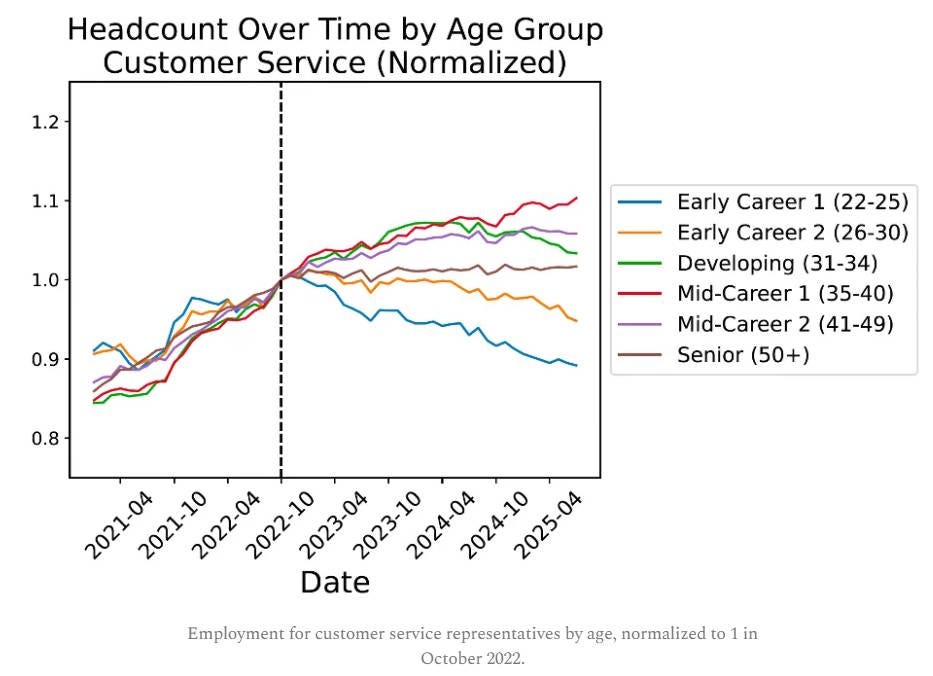

Our first key finding is…substantial declines in employment for early-career workers (ages 22-25) in occupations most exposed to AI, such as software developers and customer service representatives. In contrast, employment trends for more experienced workers in the same occupations, and workers of all ages in less-exposed occupations such as nursing aides, have remained stable or continued to grow.

Our second key fact is that overall employment continues to grow robustly, but employment growth for young workers in particular has been stagnant since late 2022. In jobs less exposed to AI young workers have experienced comparable employment growth to older workers. In contrast, workers aged 22 to 25 have experienced a 6% decline in employment from late 2022 to July 2025 in the most AI-exposed occupations, compared to a 6-9% increase for older workers. These results suggest that declining employment AI-exposed jobs is driving tepid overall employment growth for 22- to 25- year-olds as employment for older workers continues to grow.

Bharat Chandar, one of the authors, has written a blog post explaining the paper’s findings:

Now, I know Erik Brynjolfsson, and I know that he is a very good and careful economist. But I’m suspicious of this particular result, for one big reason: I can’t see any reason why the employment effect of AI should fall only on recent college graduates.

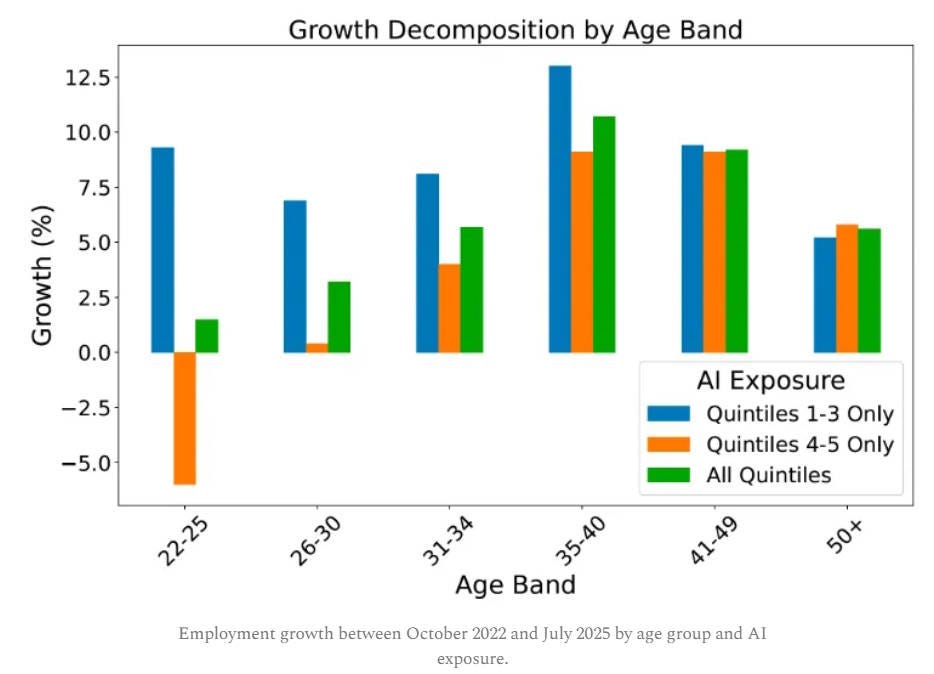

Brynjolfsson et al. find that since late 2022, employment has grown robustly among most segments of the workforce. Only very young workers who are also highly exposed to AI have seen their employment numbers fall:

Notice that the workers in their 30s, 40s, and 50s who are judged to be most heavily exposed to AI have seen robust employment growth since late 2022.

How can we square this fact with a story about AI destroying jobs? Sure, maybe companies are reluctant to fire their long-standing workers, so that when AI causes them to need less labor, they respond by hiring less instead of by conducting mass firings. But that can’t possibly explain why companies would be rushing to hire new 40-year-old workers in those AI-exposed occupations!

Think about it. Suppose you’re a manager at a software company, and you realize that the coming of AI coding tools means that you don’t need as many software engineers. Yes, you would probably decide to hire fewer 22-year-old engineers. But would you run out and hire a ton of new 40-year-old engineers? Probably not, no! And yet Brynjolfsson et al.’s data says that this is exactly what’s been happening since 2022. Empirically speaking, it’s a great time to be a middle-aged software engineer or customer service rep!

Now, maybe we can quickly come up with a story to explain this. Maybe older workers gain human management skills that complement AI, while younger workers are valued primarily for their technical abilities, putting them in more direct competition with AI, or something like that. But come on — before an AI critic saw this result, would they have predicted that the coming of AI would lead to a hiring bonanza for middle-aged customer service reps? Probably not.

Unless we can come up with a compelling story for why AI should only replace the young, this finding smacks a bit of “specification search”. During any 3-year period, there will probably be some group of workers who do a little bit worse than the rest. We can’t just keep pointing at those groups and yelling “It’s AI! It’s AI!”. Yes, any such group might be “the canary in the coal mine”, but we should have some reason to believe ex ante that they’re a canary instead of a pigeon or a sparrow.

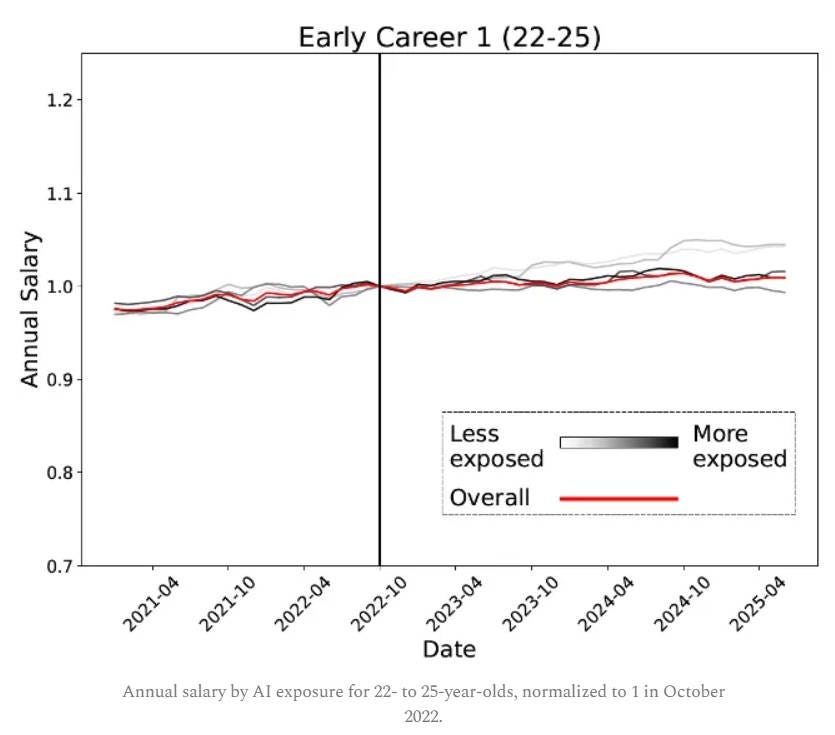

It’s also a bit fishy that Brynjolfsson et al. find zero slowdown in wages since late 2022, even for the most exposed subgroups:

This just doesn’t seem to fit the story that AI is causing a large drop in labor demand. As long as labor supply curves slope up, reducing headcount should also reduce wages. The fact that it doesn’t suggests something is fishy.

There’s also the question of whether Brynjolfsson et al. chose the right measure of AI exposure. Their main measure is one of the ones from Eloundou (2024). Eckhardt and Goldschlag also look at that same measure; it’s one of the two that do show a slight increase in unemployment among AI-exposed workers. So that’s reassuring — we know there’s some consistency between the two papers.

But EIG’s finding means that it’s important to check all available (and credible) measures of AI exposure. Brynjolfsson et al. should probably check the measures from Felten et al. (2021), Webb (2022), and others.

They do use one other measure of exposure — the Anthropic Economic Index. This is a measure of how often people ask Anthropic’s LLM, Claude, about a particular topic. Of course, this could also just be measuring how much people use AI to complement their own skills. So Brynjolfsson et al. basically just asked the LLM whether it thought the people writing in to ask Claude about each task were trying to avoid doing that task, or make themselves better at doing it. This is how they decide which jobs are in danger of being replaced, versus which jobs will simply see productivity boosts from AI.

Honestly, I don’t put a lot of stock in this measure of AI exposure. We need to wait and see if it correctly predicts which types of people lose their jobs in the AI age, and who simply level up their own productiveness. Until we get that external validation, we should probably take the Anthropic Economic Index with some grains of salt.

So while Brynjolfsson et al. (2025) is an interesting and noteworthy finding, it doesn’t leave me much more convinced that AI is an existential threat to human labor. Once again, we just have to wait and see. Unfortunately, the waiting never ends.

Update: Josh Gans has a good post about why we might see companies hiring older workers in AI-exposed occupations:

Basically, the idea is that experience is a complement to what AI can do, while formal education (which is all young workers have) is a substitute. This would essentially just mean that AI is making on-the-job training a lot more important. Which is good news if we can solve the traditional problem associated with on-the-job training, which is “Who pays for it?”. More on this in an upcoming post.

I think you're right that it's very hard to tell right now what AI does or will do to the job market.

But the effect in Brynjolfsson et al. is actually *exactly* what I'd expect to be happening if AI were to start having a major impact in these industries.

Think about it: To use current AI tools and capabilities well - especially in areas such as coding, but also law, supply chain management, whatever - you need a certain level of expertise and domain knowledge.

This is exactly what middle-aged developers and managers have. They are the ones that can prompt and set up AI systems in a way that makes sense and increases productivity in their respective industry and company. They have the expertise and a stake in making things better and faster (especially if they're switching jobs, as this often implies they're driven by a hunger for change that couldn't be fulfilled when staying put).

Entry-level workers on the other hand - while possibly adept at using AI tools for personal needs and wishes - will almost uniformly lack the deep domain knowledge and company- or industry-specific expertise to prompt and set up AI correctly in their new job. That takes time.

I'm also quite skeptical whether we really are starting to see the impact of AI on the labor market. But as to what we'd be seeing if it were to happen, this is exactly what I would expect.

Dunno whether I’m hallucinating, but there seems an obvious answer to this. AI at the moment is v. powerful but prone to mistakes / making stuff up. Therefore, deployment at the moment is replacing young kids but needs older, wiser heads to check the output. An analogy might be Tesla’s FSD - clearly getting good but needs someone to keep an eye on it.

Therefore, Brynjolfsson’s finding is exactly what you’d expect where companies are replacing new young recruits with cheaper AI but still need managers to make sure the AI doesn’t make bad mistakes.

Obviously, when the AI error rate drops significantly (a path already seen with GPT5), then it comes for the managers too.