At least five interesting things: Cool research edition (#68)

AI and jobs; Bernie's bad chart; Personalist leaders and growth; AI vs. trolls; Chinese transshipment; marriage facts

I’ve got quite a few great podcasts for you today. One is this excellent live show that Erik Torenberg and I did with Dwarkesh Patel, in which we interview Dwarkesh about his thoughts on AI and the economy. The picture of me here is quite silly-looking, but the conversation was excellent:

I also went on Pascal-emmanuel Gobry’s podcast to debate him about illegal immigration:

And some Japanese media folks at a company called Glasp interviewed me about AI and jobs, and about foreign direct investment in Japan!

Finally, here’s an episode of Econ 102, where Erik and I discuss Javier Milei and various other topics:

Anyway, on to the roundup!

1. It doesn’t look like AI is taking jobs yet

It’s practically conventional wisdom that AI is going to take jobs away from large numbers of humans, leaving them without anything useful to do in the economy. People are so convinced of this that they’ll jump at practically any hint in the data that allows them to believe that it’s happening. A little while ago I wrote a post about why both economists and popular commentators are getting way over their skis on this:

Anyway, Sarah Eckhardt and Nathan Goldschlag of the Economic Innovation Group have a good new report on this, which shows that as far as we can tell, AI isn’t taking jobs yet — at least, not on any measurable scale.

Eckhardt and Goldschlag start with a measure of predicted AI exposure for various jobs. These measures don’t tell you which jobs are going to be replaced by AI; instead, they just tell you which jobs currently involve more tasks that can probably be done by AI. These measures actually have a pretty good track record at predicting which workers will end up using AI.

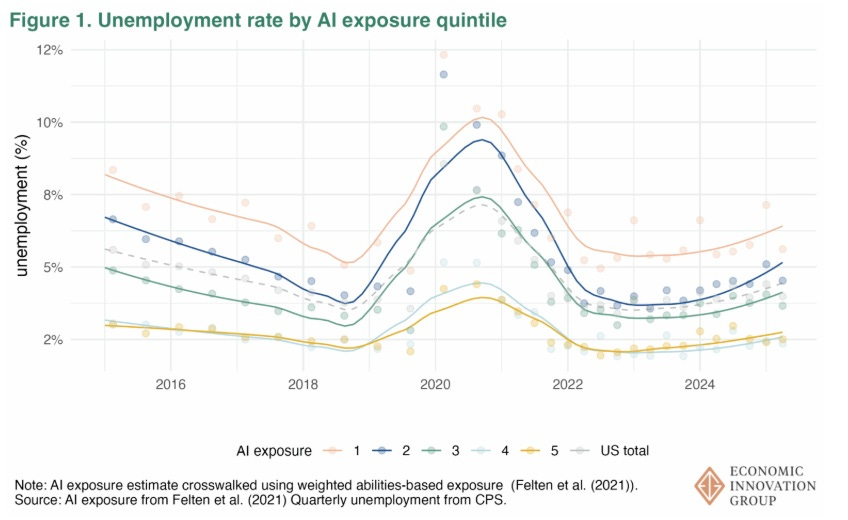

Basically, Eckhardt and Goldschlag find no correlation — or even a negative correlation — between that measure of AI exposure and any measure of labor market distress. For example, here’s the unemployment rate of workers with varying degrees of predicted AI exposure (1 is the least exposed, 5 is the most exposed):

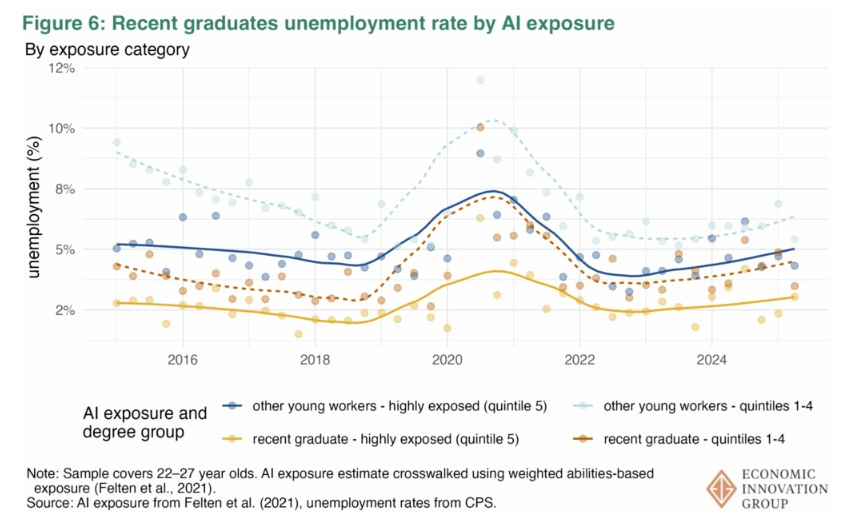

There has been a recent rise in unemployment, but it’s concentrated among the people who are least exposed to AI, while those who are the most exposed almost all still have jobs. The same is true when we look only at recent college graduates, who have been the focus of the most concern in the media:

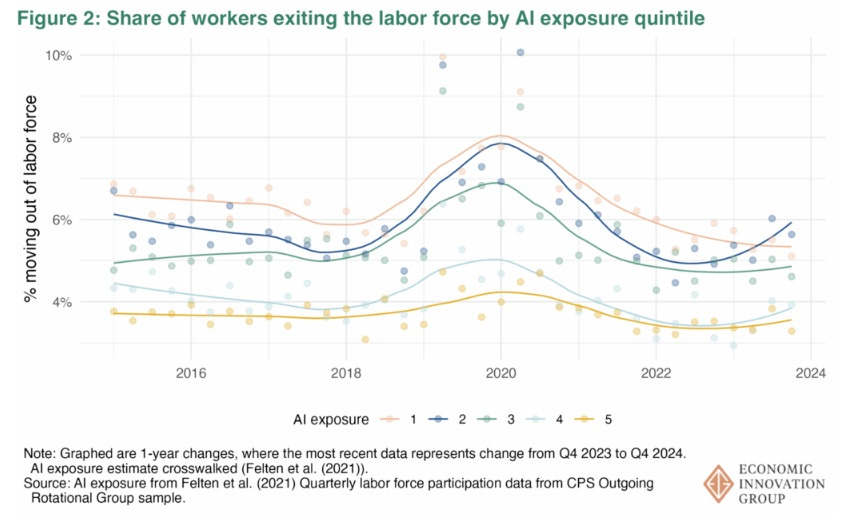

And the same is true when we look at which workers are exiting the labor force completely:

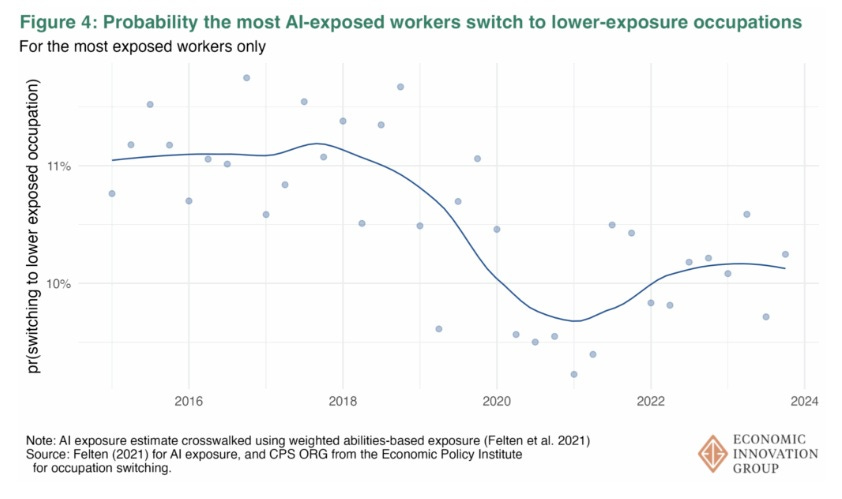

And one more interesting finding is that the most-exposed workers are actually less likely to switch to less-exposed occupations than they were before generative AI hit the market! In other words, coders and paper-pushers are not becoming plumbers to protect themselves from AI:

The researchers also try using alternative measures of AI exposure, and they find pretty much the same thing.

In other words, AI job displacement just hasn’t happened yet. It may happen in the future, but so far, every time people have jumped at a particular data point to claim it’s finally happening, it has turned out to be a mirage.

2. Bernie’s bad chart

Bernie Sanders and his followers deeply believe that America’s economy is in a prolonged state of crisis — that capitalist economic policies have steadily immiserated the American public, creating a country where regular people are economically drowning even as corporate fat cats enrich themselves. Their absolute faith in this narrative often leads them to interpret economic statistics in dubious or even ridiculous ways. The latest example of this is when Bernie Sanders posted a chart of housing versus wages:

This is a pretty ridiculous chart. Why would you plot home prices on the same y-axis as weekly income? Does anyone think these two things should be even remotely close to the same size? Do we think people should be able to afford a house on a single week of income? That’s ridiculous.

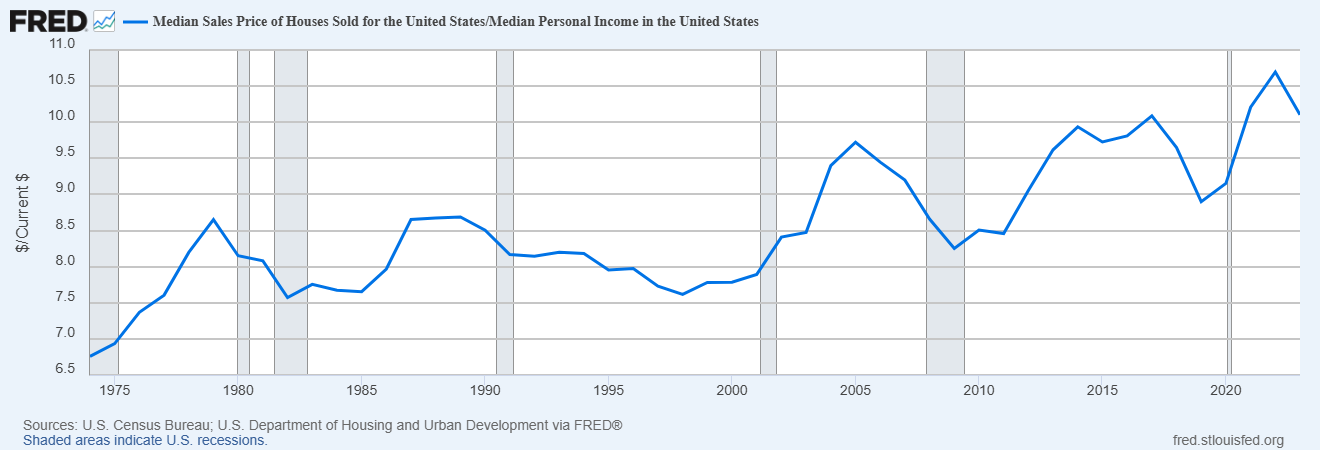

A non-ridiculous way to present this data would be to divide home prices by weekly earnings. That would show us how many weeks a typical worker would need to work in order to afford a home. But actually, the “median weekly earnings” number is for full-time workers only, so instead we should use median personal income, which counts everybody. Here’s what that looks like:

In the 80s and 90s, it took about 8 years of work to afford a home. Since then, the number has climbed to about 10 years — a significant and concerning drop in affordability, but not a catastrophic drop. A breakdown by the Economic Innovation Group shows that mortgages are about as affordable as they ever were, but down payments have gotten less affordable:

While the drop in housing affordability over the past half century is certainly a problem, it’s not the kind of crisis that Bernie paints it as. Using silly charts in service of alarmist narratives ultimately just weakens trust in your movement — or at least, it should.

3. Personalist dictatorships are probably bad for the economy

The three most powerful countries in the world are now all ruled by strongmen. In China, Xi Jinping has subdued all rivals, and concentrated what used to be a dispersed bureaucratic oligarchy under his own personal rule. In Russia, Putin is effectively an emperor. The U.S. is still officially a democracy, but democratic norms and institutions are eroding rapidly, and in April a majority of Americans called Trump a “dictator”.

The question is what effect these personalistic regimes will have on the economy. China’s growth over the past four decades pretty much proves that democracy isn’t necessary for a strong or even dominant economy. But there’s a difference between countries ruled by a single strongman, and countries ruled by a system of elite institutions that distribute power among a number of oligarchs.

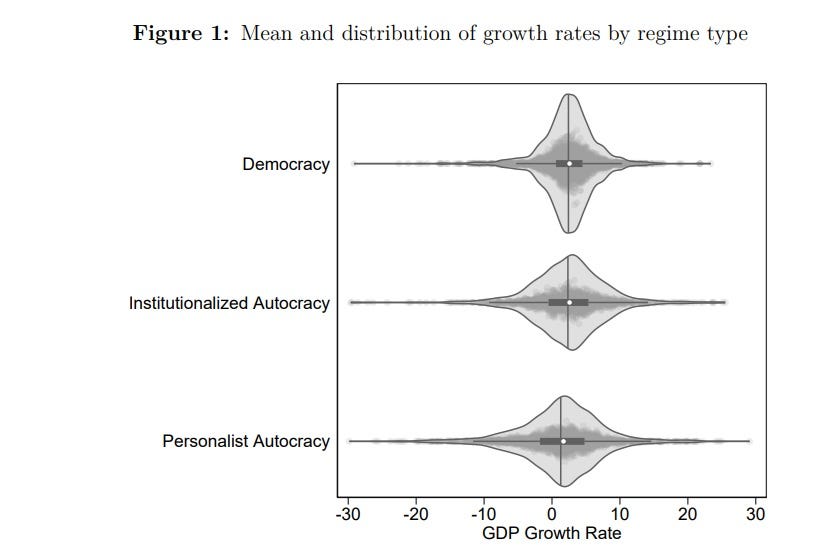

A new paper by Blattman, Gehlbach, and Yu shows that personalist regimes tend to experience lower economic growth than either democracies or autocracies with more distributed power. The difference isn’t huge, but you can see it on a graph:

It’s not clear which direction the causation runs here; it could be that countries with bad economies tend to turn to strongmen to save them. But Blattman et al. test for this using variables that tend to predict regime transitions, and they don’t find any change. That implies that personalist regimes actually make mistakes that slow down economic growth.

Xi, Putin, and Trump certainly don’t exactly seem to be violating that rule of thumb. China’s growth has slowed relentlessly under Xi, and his industrial policy seems to be simply driving Chinese companies into unprofitability rather than extricating the country from its economic slump. Putin’s war in Ukraine is slowly crushing the life out of the Russian economy, while Trump’s tariffs continue to wear down the resilient U.S. economy.

The trend toward strongmen is a bad one.

4. Will AI save us from the social media trolls?

Does it ever seem like modern political discourse is dominated by crazy idiots? Well, that’s because it is. In a new paper entitled “Dark personalities in the digital arena: how psychopathy and narcissism shape online political participation”, Ahmed and Masood find that your intuition isn’t wrong:

This cross-national study investigates how psychopathy, narcissism, and fear of missing out (FoMO) influence online political participation, and how cognitive ability moderates these associations. Drawing on data from the United States and seven Asian countries, the findings reveal that individuals high in psychopathy and FoMO are consistently more likely to engage in online political activity….Conversely, higher cognitive ability is uniformly associated with lower levels of online political participation. Notably, the relationship between psychopathy and participation is stronger among individuals with lower cognitive ability in five countries, suggesting that those with both high psychopathy and low cognitive ability are the most actively involved in online political engagement.

Almost everyone blames recent political trends on their chosen enemy group, but the real culprit is social media, which has elevated the worst people in our society to positions of influence from which they were previously shut out.

What force can defeat the terrible power of social media and its armies of crazy idiots? In my Fourth of July post, I expressed hope that AI algorithms could be harnessed to defeat the hordes of humanity’s worst:

LLMs give platforms the ability to cheaply and quickly filter content according to sentiment. Simply having an LLM downrank angry content and uprank positive content would lean against the natural tendencies of social media technology. Call it Digital Walter Cronkite.

Of course, that solution would depend on the willingness of platform owners like Elon Musk to unleash algorithms in service of moderation and reasonability. That seems a bit like wishful thinking, I admit.

But there’s another possibility, which is that AI itself will simply naturally drive humans off of social media, by generating infinite amounts of slop. A new paper by Campante et al. finds evidence that AI-generated images nudge news consumers toward more trustworthy human-gatekept media:

We study how AI-generated misinformation affects demand for trustworthy news…Readers were randomly assigned to a treatment highlighting the challenge of distinguishing real from AI-generated images. The treatment raised concern with misinformation…and reduced trust in news…Importantly, it affected post-survey browsing behavior: daily visits to [the mainstream newspaper’s] digital content rose by 2.5%…[S]ubscriber retention increased by 1.1% after five months…Results are consistent with a model where the relative value of trustworthy news sources increases with the prevalence of misinformation, which may thus boost engagement with those sources even while lowering trust in news content.

A similar effect might happen with AI agents, which are already flooding social media with trash commentary. As X and other social media companies lose the battle against the bot swarms, human users may stop relying on those feeds for their window on the world. The psychopaths and attention-seekers might simply get drowned out in the automated cacophony.

That would be a weird end to the age of mass social media, but honestly it’s not the worst ending I could think of.

5. No, China isn’t just selling stuff to America through third countries

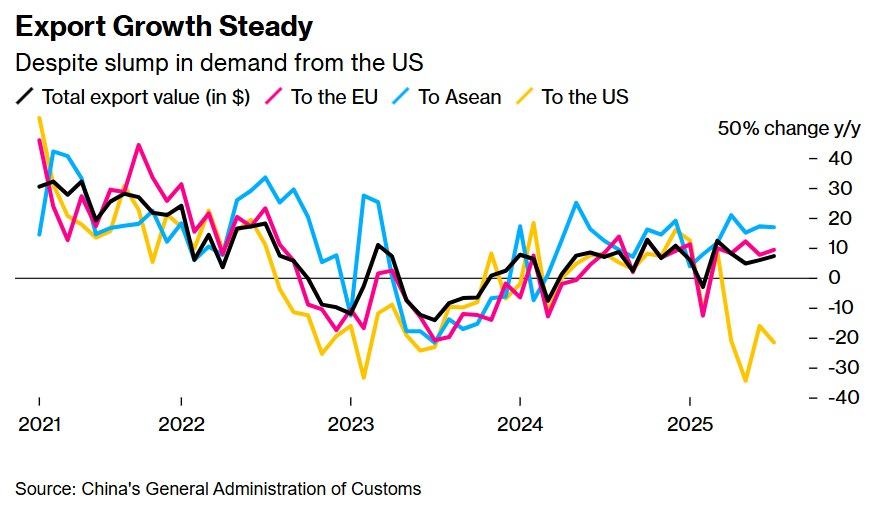

The American and Chinese economies continue to decouple. Even though Trump keeps “pausing” his tariffs on China, China is selling less and less to America:

But you’ll notice that China’s exports to Europe and Southeast Asia are still growing strongly. This has led some commentators to claim that China is simply shipping its good through third-party countries, avoiding tariffs (or the threat of tariffs) by essentially just slapping a different “made in” label on stuff that was actually made in China.

Those claims are wrong. You can see that they’re wrong by looking at the actual products that China is selling to countries in Southeast Asia (the region usually accused of transshipping Chinese goods to the U.S.), versus the products it used to sell to the U.S. The two sets of products don’t match up very well, meaning that only a modest portion of Chinese trade with Southeast Asia could reflect diversion of trade from the U.S. Gerard DiPippo did this exercise:

Facing U.S. tariffs, China’s exports to the U.S. are down—while exports to Southeast Asia are up. Is that trade diversion and potential transshipment? My estimate: at most 34% of the increased PRC exports to SE Asia in Q2 could reflect trade diverted from the United States.

In fact, this is an upper bound. Many of the countries being accused of transshipping Chinese goods — Mexico, Vietnam, etc. — have their own industries as well, which export a lot to the U.S. Increased U.S. imports from those countries are likely to at least partially — or perhaps mostly — be locally made goods.

All this goes to show that you can’t draw conclusions about decoupling just from macro data.

6. The rise of the power trad couples

There are a number of popular ideas out there about who marries whom. One is that rich men primarily want physically attractive wives and don’t care about social status, education, and so on. Another is that power couples tend to be dual earners.

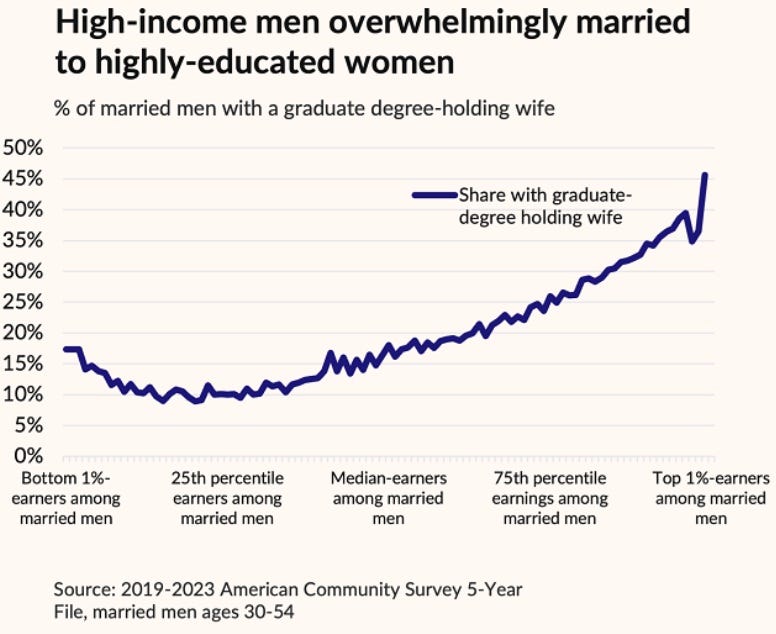

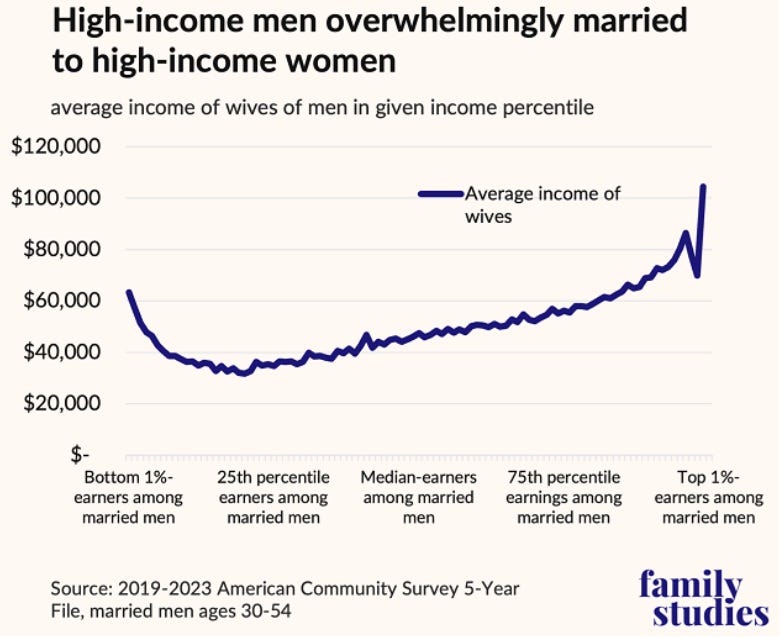

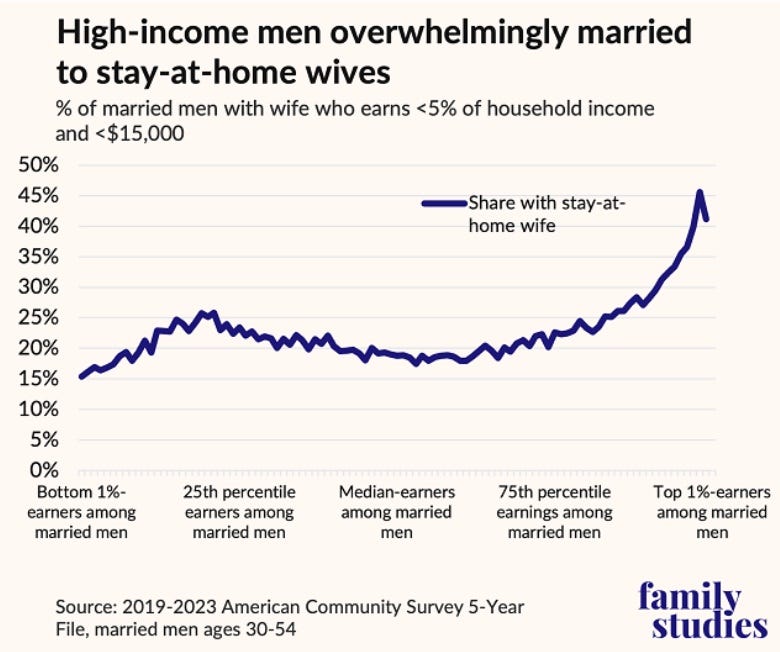

In fact, both of these stereotypes are wrong. As Lyman Stone shows in a post for the Institute for Family Studies, rich men tend to marry highly educated, high-earning women women who become housewives after marriage. Here are some charts:

I don’t like the use of the word “overwhelmingly” in any of these charts, but the point is clear — rich men, who presumably have greater choice in who they marry, often tend to prefer women who are educated and high-income before marriage, but many of these women become homemakers after marriage. Call it the “power trad” couple.

Glad you linked to Lyman Stone's piece. I am not sure that "stay at home" is the best alternative term to "wage earner." I know this demographic and they are not "at home" but in sitting on community, school, and foundation boards; in churches; raising money; leading cultural organizations, political organizations; managing staff, shopping, influencing -- all in all, super active, as well as raising the children.

Just bonkers to me that while the leading AI companies are forecasting “complete automation” in the next decade, the data doesn’t support ANY automation at all yet for the occupations most exposed to it