Nobody knows how many jobs will "be automated"

Whatever that even means.

Good news: Substack links are working on Twitter again, so you can share this post to your heart’s content!

One thing I’ve learned in my years of writing about the economics of AI is that it’s pretty much impossible to get people to think about this issue in terms of anything except job loss. The “folk model” of automation is that it throws humans out of work — today you had a job performing some sort of valuable work, and tomorrow you’re on the welfare rolls. This is not how things have worked out in the past — we’ve been deploying automation technology for centuries, and as of 2023, pretty much every human who wants a job has a job. But there’s basically no way to get people to believe that this next wave of automation will be the one that finally sends humans into obsolescence.

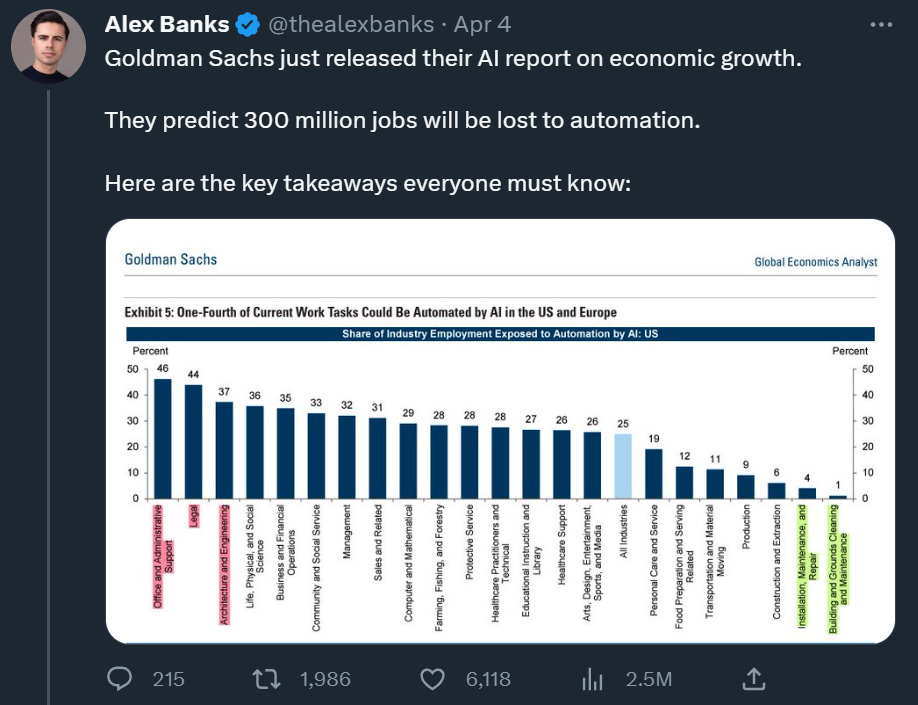

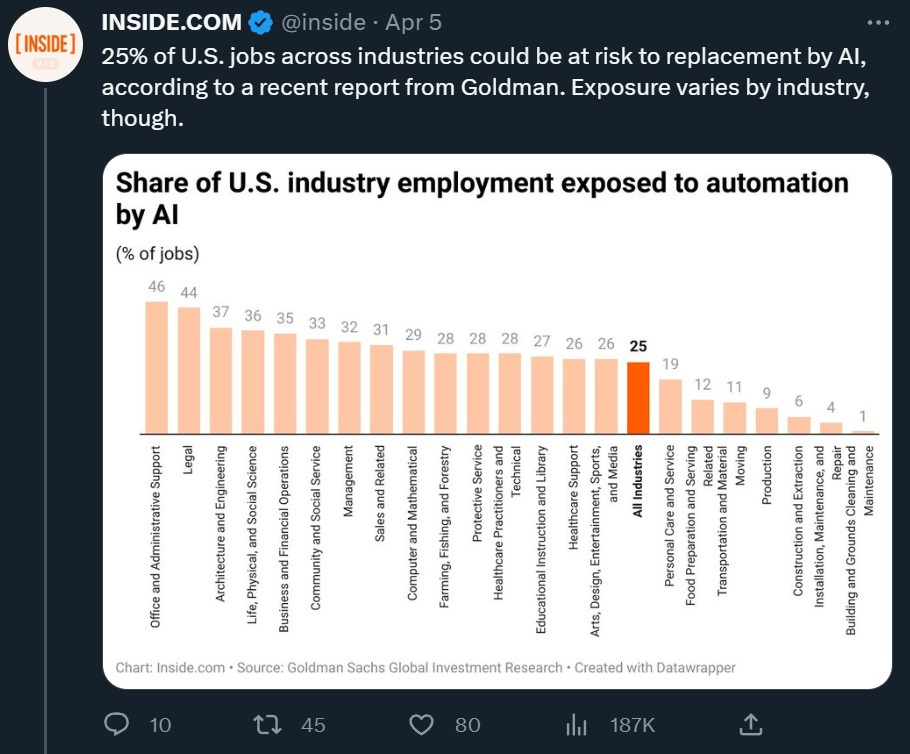

Those fears are amplified by a never-ending, relentless parade of media reports declaring that some large percent of jobs are “vulnerable to automation” or “will be lost to automation”. For example, here is Alex Banks tweeting about a recent Goldman report:

Here’s Inside.com, reporting on the same study:

In fact, the Goldman report says nothing of the kind, as we’ll discuss in a moment. In fact, the researchers who put out this sort of report have been improving their language and methodology substantially in recent years; the media reports simply haven’t reflected the positive shift.

But first, let’s go over a quick history of this sort of report.

We’ve been here before, and it didn’t make much sense the last time

Over the years there have been a lot of studies claiming that X% of jobs are at risk of automation. For example, here’s Vox in 2018:

[R]esearchers at Citibank and the University of Oxford estimated that 57 percent of jobs in OECD countries — an international group of 36 nations including the U.S. — were at high risk of automation within the next few decades. In another well-cited study, researchers at the OECD calculated only 14 percent of jobs to be at high risk of automation within the same timeline. That’s a big range when you consider this means a difference of hundreds of millions of potential lost jobs in the next few decades.

Here’s PriceWaterhouseCoopers in 2016:

[T]he estimated proportion of existing jobs at high risk of automation by the early 2030s varies significantly by country. These estimates range from only around 20-25% in some East Asian and Nordic economies with relatively high average education levels, to over 40% in Eastern European economies where industrial production, which tends to be easier to automate, still accounts for a relatively high share of total employment.

Here’s another from the World Economic Forum in 2016, giving a number of about 40%.

In other words, we’ve been getting warnings about mass job loss to automation (or “vulnerability” to automation) since well before ChatGPT and its cousins emerged on the scene. Five to seven years have passed since the last big round of warnings, but as of 2023, the percent of prime-age Americans with jobs is larger than it was when those studies came out (and near all-time highs):

This brings up a key question: What the heck does it mean for a job to be automated?

Does it mean that a human is replaced by a machine and goes onto the welfare rolls?

Does it mean that a human is replaced by a machine and goes and gets a similar job for a different employer?

Does it mean that a human is replaced by a machine and goes and moves to a different kind of job with the same employer?

Does it mean that a human is replaced by a machine and goes and gets a different kind of job with a different employer?

Does it mean that a human uses a machine to do some of her job tasks and does less work overall, while retaining the same job title with the same employer?

Does it mean that a human uses a machine to do some of her job tasks, while taking on additional new job tasks, and retaining the same job title with the same employer?

Does it mean that a human uses a machine to do some of her job tasks, while taking on additional new job tasks, and changing her job title while remaining with the same employer?

…and so on. None of the above studies define exactly what it means for “a job to be automated”, yet the differences between the potential definitions have enormous consequences for whether we should fear or embrace automation. If you tell a worker “You’re going to get new tools that let you automate the boring part of your job, move up to a more responsible job title, and get a raise”, that’s great! If you tell a worker “You’re going to have to learn how to do new things and use new tools at your job”, that can be stressful but is ultimately not a big deal. If you tell a worker “You’re going to have to spend years retraining for a different occupation, but eventually your salary will be the same,” that’s highly disruptive but ultimately survivable. And if you tell a worker “Sorry, you’re now as obsolete as a horse, have fun learning how food stamps work”, well, that’s very very bad.

Anyway, not only do the studies fail to define what it means for a job to be automated, they don’t even try to figure out the aggregate labor market impact of this automation. If one job is destroyed by automation and two more are created for higher wages, workers obviously won out. But this type of study will look at that outcome and say only that “one job was automated”, which sounds like a loss for workers.

On top of all that, the way these studies assess which jobs are at risk of being “automated” is highly suspect. For example, let’s look at Frey and Osborne (2013), the paper behind the Oxford/Citibank report. Here’s how they decided whether an occupation was automatable:

First, together with a group of ML researchers, we subjectively hand-labelled 70 occupations, assigning 1 if automatable, and 0 if not…Our label assignments were based on eyeballing the O∗NET tasks and job description of each occupation…The hand-labelling of the occupations was made by answering the question “Can the tasks of this job be sufficiently specified, conditional on the availability of big data, to be performed by state of the art computer-controlled equipment”. Thus, we only assigned a 1 to fully automatable occupations, where we considered all tasks to be automatable. To the best of our knowledge, we considered the possibility of task simplification, possibly allowing some currently non-automatable tasks to be automated. Labels were assigned only to the occupations about which we were most confident.

So basically, these researchers went through a database of job descriptions and subjectively decided which ones they thought could be replaced by computers. They then tested their own predictions by correlating them with various numerical descriptors in the database (e.g. how much “manual dexterity” or “originality” a job is said to require, on a 3-point scale), and found that their own subjective assessments correlated strongly with these attributes.

To be perfectly blunt, this seems like a pretty poor method for assessing the automatability of jobs. First, it’s clear that the authors have a hypothesis about which kinds of jobs are automatable — basically, things that don’t require much originality, manual dexterity, or human interaction — and then basically assume that hypothesis is true, and classify jobs accordingly. This is basically just humans eyeballing a very general description of a job whose specifics they don’t understand at all, and deciding whether it’s the kind of thing they think a computer could replace.

Respectfully, I don’t think that sort of methodology adds much to our understanding of how automation will affect jobs, either specifically or in the aggregate. If the list of tasks associated with each job in the database isn’t actually a complete description of what the job entails — if there are subtle job requirements that aren’t listed in the Labor Department’s brief sketch — then the whole analysis could be massively thrown off. For example, few job descriptions are likely to include tasks such as “massaging the ego of your boss so that he doesn’t make stupid time-wasting decisions”, and yet in reality this is probably a significant component of many jobs! And it’s also something that could be a lot harder to automate than, say, “filling out Excel spreadsheets” — or at the very least, requires a much different kind of automation. The authors also ignore the possibility that workers might add new tasks to their jobs when the old tasks get automated — for example, maintaining a drill press rather than drilling things by hand.

Also, this caught my eye:

The fact that we label only 70 of the full 702 occupations, selecting those occupations whose computerisation label we are highly confident about, further reduces the risk of subjective bias affecting our analysis.

How on Earth does subjectively throwing out 90% of your data reduce “subjective bias” in a quantitative analysis? That makes no sense at all to me. But anyway, I digress.

The point here is that predicting the impact of automation on specific jobs is very very hard, especially when A) you don’t actually define what it means for a job to be “automated”, B) you don’t know the details of the jobs in question, and C) you have only some vague general guesses as to what automation can and can’t do. Breathless reports that 57% or 40% or 14% of American jobs are vulnerable to automation can thus safely be ignored.

Fortunately, the recent round of studies has improved mightily, both in terms of goals and in terms of methodology. Unfortunately, the apocalyptic media reports have not similarly improved.

Better studies, same old media freakouts

The first thing that the studies on job automation have improved is the target of their research. Frey and Osborne (2013) tried to assess which jobs would be completely automated, by viewing each job as nothing more than the sum of the tasks described in the government database. Goldman Sachs’ study, by Briggs and Kodnani, isn’t publicly available, but this is from a summary on Goldman’s website:

Analyzing databases detailing the task content of over 900 occupations, our economists estimate that roughly two-thirds of U.S. occupations are exposed to some degree of automation by AI. They further estimate that, of those occupations that are exposed, roughly a quarter to as much as half of their workload could be replaced. But not all that automated work will translate into layoffs, the report says. “Although the impact of AI on the labor market is likely to be significant, most jobs and industries are only partially exposed to automation and are thus more likely to be complemented rather than substituted by AI,” the authors write.

In other words, the Goldman researchers don’t make claims about which jobs will have all of their tasks automated, only about which jobs will have at least some of their tasks automated. This is a much easier claim to make.

Goldman’s researchers also recognize that when only some of a job’s tasks are automated, it doesn’t necessarily mean there will be layoffs in that occupation, and that automation often ends up complementing a worker’s effort instead of substituting for it. In other words, they recognize the fundamental difference between automating jobs and automating tasks. Or, as I once put it:

The Goldman team also recognizes that new technology leads to the creation of new kinds of jobs. From an AEI summary of the Goldman study:

Technology can replace some tasks, but it can also make us more productive performing other tasks, and create new tasks — and new jobs. GS cites research that finds “60% of workers today are employed in occupations that didn’t exist in 1940, implying that over 85% of employment growth over the last 80 years is explained by the technology-driven creation of new positions.” The GS operating assumption here is that GenAI will substitute for 7 percent of current US employment, complement 63 percent, and leave 30 percent unaffected.

Note that this is utterly different from the way that Alex Banks, Inside.com, and other outlets like Forbes reported on the Goldman study. Banks says that Goldman is predicting 300 million lost jobs, although Goldman specifically predicts that most automation won’t mean job losses. Forbes says 300 million jobs “lost or degraded”, even though Goldman says the vast majority of jobs will be “complemented” rather than degraded. And Inside.com claims that Goldman says 25% of jobs are “at risk of replacement”, even though Goldman’s actual figure is 7%. A lot of people are so used to the “robots take our jobs” narrative that they report every result they see through that warped and distorted lens.

To their credit, outlets like Bloomberg and CNN interpreted the Goldman study correctly. But “AI will increase labor productivity while forcing a small number of people to find new jobs” is not the kind of story that goes viral on social media, while “300 million jobs will be lost” definitely is that kind of story. People love to read about the impending apocalypse, and it’s the media’s responsibility not to indulge that desire.

Anyway, I can’t see the Goldman study’s methodology, but I do know that researchers in general have improved on the old methodology of “just eyeball a job description and decide whether you think a computer could do it”. Felten, Raj, and Seamans (2018) developed a more credible method. They still used subjective expert assessments, but what the experts assessed was whether progress in various AI capabilities would map to all of the various human abilities in the O*NET job database. This method still has subjectivity, but it’s subjectivity about whether automation affects a certain job rather than whether it replaces it. That’s a much humbler thing to assess! Felten et al. also find that these assessments do a good job of predicting which job descriptions get revised by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (meaning that the job changed in some way). That’s not proof that the methodology is perfect, but it’s a good check.

In a new 2023 paper, the authors use this method to guess which jobs will be affected by the new wave of generative AI. Like the Goldman Sachs team, they’re extremely circumspect about whether having your job affected by AI is a good or bad thing:

One might imagine that human telemarketers could benefit from language modeling being used to augment their work. For example, customer responses can be fed into a language modeling engine in real time and relevant, customer-specific prompts quickly fed to the telemarketer. Or, one might imagine that human telemarketers are substituted with language modeling enabled bots. The potential for language modeling to augment or substitute for human telemarketers work highlights one aspect of the AIOE measure: it measures “exposure” to AI, but whether that exposure leads to augmentation or substitution will depend on specifics of any given occupation.

Studies like this benefit from their modest objectives. Instead of telling us who will be “automated”, they tell us who’s more likely to be affected by automation in some way. Obviously we’d like to know whether it’ll be a good way or a bad way. But the truth is that no one knows that yet, and economists do the world a service by refusing to pretend that they do know.

When Ford made cars cheaper to make, that meant more, better-paying car jobs, not fewer. Why? Because back then, lots more people wanted cars than could afford them.

I distrust any "AI economics" that doesn't look at demand elasticity. If it's a service that people would like to have a lot more of, then AI should not reduce but increase employment and wages.

Most people not named Buffett or Musk would like a lot more on-call therapy, personal medicine, secretarial help, legal expertise, custom programming, and favorite genre fiction than they currently get. If AI partially automates those industries, it ought to mean not less but more worker dollars, and likely more and better (if different) jobs.

Which workers? Good question, the winners could easily be different than the current workers. But it should still be a workers' win, unlike the 80s or 90s.

Could AI *fully* automate those and other industries, laying off everybody? Sure; just look at what happened to all America's horses after cars got cheap. But when you're talking "humans, as economically useful as horses," that's no longer a story about scarcity and economics. Full automation of cognitive work would be a society whose big problem for a generation wasn't scarcity allocation by economics, but wealth allocation by politics.

So if it's partial automation, we should look at elasticity and see how many jobs will benefit, not just suffer.

And if it's full automation, humans-as-horses for medical and legal and writing and programming? Well, we should admit that's such a different future that it should be an argument about pensions or UBI, not about "keeping good jobs."

Having spent a 40 year career in factory automation, I am always amazed at how shallow the jobs-versus-automation arguments are. Why not this: "We can only have more and better things if we automate..." So it's really just a choice. Stay the same or improve.

The precise components inside of our appliances and automobiles - whether internal combustion or EV - could not be manufactured to the precision and volume required for their performance without the automation of machine tools and robots. Do we want these things or not? This isn't just limited to "touch" labor. Many of the products we appreciate could not exist if they were designed by hand. The circuitry inside a microchip would not exist were it not for the design and modeling tools that assist engineers to iterate such complex alternatives. Not to mention that automation makes dangerous jobs safer.

Every form of automation ever invented just amplified the know-how of humans to do more and better things. I would love to see a study on the impact of removing the automation already in place to the benefit of labor!

There may be reasons to consider the social impacts of AI, just like there is for genetic cloning, just like there was for bringing moon rocks back to earth. But job loss isn't one of them.