Good cities can't exist without public order

Anarchy or urbanism: You must choose one.

Note: I apologize for slightly sparse posting this week — I sliced my thumb very badly the other day while opening a box, and it has been difficult to type. Regular posting will now resume.

Anyone who reads this blog knows that I’m a huge fan of dense, walkable cities. Much of my enthusiasm comes from living in Japan for several years, and I’ve written a bunch of posts about why Japanese cities are so especially great. Here was the most relevant one for today’s post:

Back home in America, I’ve called for a bunch of changes to make our cities better places to live. Most importantly, we need more housing density and better transit. These are the two main goals of the YIMBY movement. I also want more commercial density — lots of shops in walkable downtown areas — which is something YIMBYs should focus on more than they do. I don’t think American cities are going to become like Tokyo — or Paris, or Singapore, etc. — anytime soon. But I think places like San Francisco, Los Angeles, Seattle, Houston, Miami, and Philadelphia can move enough in that direction to make a big difference in America’s quality of life, and probably in our economic productivity as well.

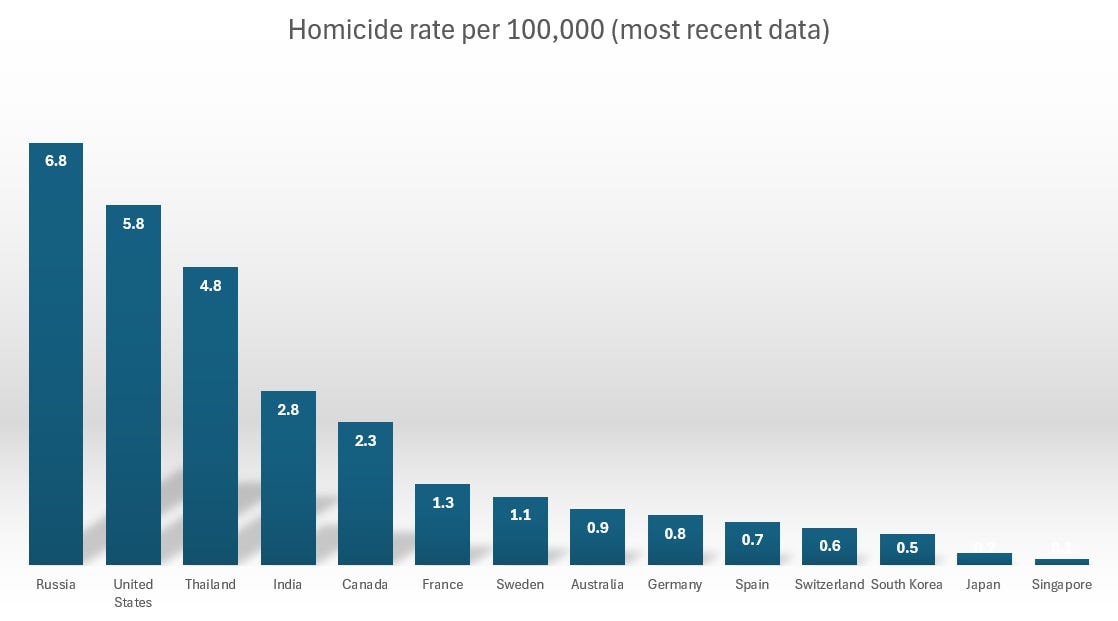

But we’ll need to change a lot about our society in order to get there. Usually, when I talk about urbanism, I talk about land use deregulation, increased transit funding, and transit cost reduction, so that we can build dense housing and transit cheaply and abundantly. And I think those policies are incredibly important. But when I suggest these policies to conservatives, or even just to politically neutral NIMBY types, the response I always get is that Japan and Europe can have nice cities because they have public order. They point out the vast disparities in violent crime between America and the rich nations of Eurasia:

With America’s high crime rates, they say, we could never have cities like that.

And I think the conservatives and NIMBYs are partially right. They’re partially wrong, in that you don’t have to have a city as safe as Tokyo in order to have lots of density and good transit. NYC has a homicide rate of about 4.6 per 100,000 as of 2023, which is about 10 times that of Tokyo and 4 times that of Paris, and yet it’s super dense and very walkable. But they’re partially right. One reason is that, just as they say, low levels of both violence and general public disorder probably make it a much more pleasant experience to walk around a downtown area. In my post about why Japanese cities are such nice places to live, I wrote:

Good public safety makes people feel safer leaving their homes — especially women, and especially at night. This makes neighborhoods more vibrant and increases the feeling of community. And when it’s safe to go outside, living in a small apartment doesn’t feel nearly as confining; no one feels like they have to hide inside their house from muggers, rapists, etc…In fact, there’s a virtuous cycle between public safety and dense walkability — the more people are out walking around, the more “eyes on the street” there are to deter crime, which in turn makes more people feel safe walking around.

In fact, there’s evidence that crime represents a sort of “congestion cost” that makes cities function less efficiently.

But there’s another effect here that’s political in nature. Both violence and general disorder probably discourage locals from supporting both housing density and public transit — in other words, they give rise to NIMBYism. Transit, especially if it’s made free or if fare-jumping is easy, allows both criminals and drugged-up disorderly types1 to reach otherwise peaceful neighborhoods. And since apartment complexes A) are cheaper to live in than single-family houses, and B) usually come with inclusionary zoning requirements that require any new complex to include some poor tenants, they also mean more poor people in the neighborhood. If a city has poor public safety and public order, this means increased danger — or at least increased anxiety — for existing residents.

This turns some people NIMBY out of concern for public safety. And NIMBYs themselves are the main obstacle to building denser cities in America. When NIMBYs tell you that America isn’t safe enough for density, they are describing their own motivations and concerns.

It’s important to note that it barely matters whether NIMBYs are right about the effect of apartment construction and transit on local crime. For example, while there are certainly a number of studies finding that adding transit increases crime near bus stops and train stations, the estimated effects are generally small, and a few studies find no effect.2 But the claim that trains bring crime to safe neighborhoods is incredibly common in American politics. Without a widespread perception of public safety and order, people will keep using NIMBY anti-development policies to try to keep anyone away from them who even might commit a crime or make a scene on the street.

We can try to simply yell at fearful NIMBYs to stop being a bunch of NIMBYs and call them racists and segregationists and petty landed gentry, but this approach historically has poor results. Instead, the country should address their concerns about violence and disorder, in order to build a constituency for urbanism in America. (And of course, needless to say, lowering crime and increasing public safety is good in and of itself.) Europe, Asia, and New York City have all largely figured out how to do this. We can learn from their successes.

Europe, Asia, and NYC put a lot of cops on the street

Matt Yglesias had a good post back in 2023 about Europe’s approach to public safety and order:

One key is gun control, of course. But another very important policy is to have a lot of police officers. Matt writes:

France has, for example, about 150,000 members of the Police Nationale, plus another 100,000 members of the Gendarmerie. They are supplemented by a Police Municipale in the cities that’s about 20,000 strong, and there are apparently about 1,000 rural guards. That’s about four officers per thousand people, while the FBI says the United States has between 2.4 and 3.4 law enforcement personnel per person, depending on how you count.

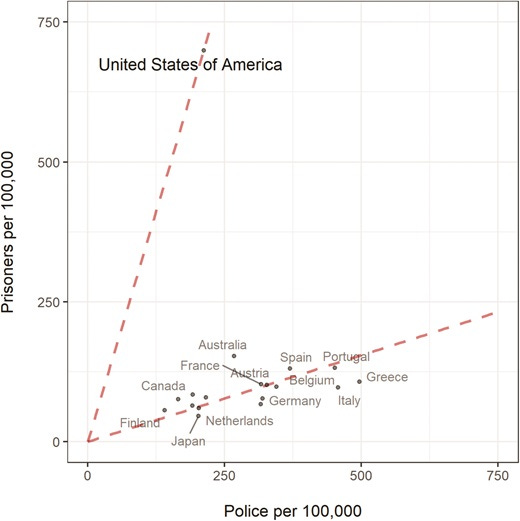

In fact, although Europe has a reputation for being lenient in terms of policy toward crime, most European countries — and East Asian countries — have more police per capita than the United States does. Here’s a chart from Lewis and Usmani (2022) showing that while America has higher rates of incarceration, other rich countries tend to have more cops:

The guys with machine guns in the image at the top of this post are, if I’m not mistaken, part of the Gendermerie Nationale, France’s national police force. You see these guys standing all over Paris with big imposing guns. Somehow it detracts from neither the walkability nor the charm of this safe, low-crime European megacity. Yglesias notes that nationalized police forces are a feature of many European countries, which might or might not be a good lesson for America.

But the real point here is that as Lewis & Usmani argue, and as Alex Tabarrok has been arguing for years, the U.S. is probably under-policed. In fact, there’s a ton of evidence that simply hiring a lot more police officers reduces crime. German Lopez did a great review of the research literature in 2021, when “defund the police” was a hot-button issue, so I’ll quote from him:

There is solid evidence that more police officers and certain policing strategies reduce crime and violence. In a recent survey of criminal justice experts, a majority said increasing police budgets would improve public safety…A 2020 study…by [Chalfin et al. for] the National Bureau of Economic Research concluded, “Each additional police officer abates approximately 0.1 homicides…

A 2005 study [by Klick and Tabarrok] in the Journal of Law and Economics took advantage of surges in policing driven by terror alerts, finding that high-alert periods, when more officers were deployed, led to significantly less crime.

And Chalfin and McCrary (2018) find that once they try to correct for certain errors in police data, the effect of policing on crime is even larger.

Increased numbers of police act through several channels, which can be difficult to disentangle with evidence. First, their presence on the street deters crime directly, because people don’t want to commit crimes in front of police. Lopez writes:

Hot spot policing…focuses on problem areas, even down to specific city blocks, with disproportionate levels of crime and violence. Police departments send officers to these places with a goal of deterring further disorder…A 2019 review in the Journal of Experimental Criminology looked at dozens of studies and found hot spot policing reduced crime without merely displacing it to other areas, and, in fact, there was evidence of “diffusion” in which crime-fighting benefits actually spread to surrounding areas. The review relied on several strong studies, including randomized controlled trials (generally the gold standard of research), suggesting that the findings were based on solid ground.

Second, the general presence of a bunch of cops in a city acts as a deterrent, because would-be criminals are afraid of being arrested and punished after the fact. There are some studies on “focused deterrence”, in which cops try to contact gangs and warn them not to commit violent crimes, and these generally find a positive effect. But there’s probably a more general deterrence effect that operates through word of mouth — when would-be criminals hear about people getting arrested, it makes them think that if they commit crimes, they too will get arrested.

The third way cops fight crime is via incarceration itself — they arrest criminals, who then get prosecuted and incarcerated, which removes repeat offenders from wider society. Scott Alexander has an excellent (and very long) review of the literature on incarceration and crime here:

The basic upshot is that removing criminals from society does prevent crime, although the financial cost of preventing crime this way — which involves supporting prisoners for many years of their lives — is very high. Hiring more police does reduce crime a lot, but the physical incapacitation piece of that is the most expensive piece. Ultimately he agrees with Tabarrok, and with Lewis & Usmani, that America is over-prisoned and under-policed.

In general, there’s an emerging consensus that the specter of long prison sentences doesn’t act as much of a deterrent to criminals, but that a high probability of being caught is a very effective deterrent. Jennifer Doleac, who studies the economics of crime, writes:

[M]ost people quickly age out of crime. There is lots of data documenting that the likelihood of committing crime increases until ages 18 to 20, then decreases. (Crime is largely a young person’s game.) That means we are incarcerating lots of people who are no longer an active threat. It’s a waste of money and does not make us safer.

Long sentences might be useful if they deterred crime — that is, if the threat of a harsh punishment provided a meaningful incentive to obey the law. But research consistently shows that increasing the probability of getting caught is far more effective. Most would-be offenders are probably not thinking very far ahead, which means the chance they’d be arrested weighs far more than the details of any future imprisonment.

(I highly recommend this long interview of Doleac by the excellent Jerusalem Demsas of The Atlantic, by the way.)

Alex Tabarrok agrees with Doleac’s prescriptions, harshly criticizing economists who assume that criminals are rational actors. He argues that a high probability of swift punishment for wrongdoing, with small punishments at first and long sentences only for a few incorrigible offenders, is the way to go.

A high probability of punishment comes from more policing. It increases the chance that a cop will be available — even nearby — to go catch a criminal. It increases the number of cops to follow up leads and investigate cases. And as Doleac writes, more cops allow for more frequent nonviolent positive interactions between the cops and the communities they police, which builds trust and improves both reporting of crimes and snitching. (Note: Congress is already working on a bill to provide more funding for detectives, to improve the abysmally low rate at which American police forces actually solve crimes.)

So anyway, this is the first big piece of what Europe and Asia do to reduce crime: Hire a lot of cops. This is also a big part of why NYC is one of America’s safest big cities. In terms of total police department employment per population, New York is second only to D.C.

Of course, gun control is also an important factor in why cities in other rich countries are safer. Some American cities have been able to enact stringent gun measures that, if enforced, would prevent most criminals from owning guns. But therein lies the rub, as they say — as Matt Yglesias has pointed out, gun control can only be enforced by a whole lot of policing.

Other rich countries are also noted for the professionalism of their police forces. America requires very little training for its officers, compared to its peer nations:

This isn’t because the U.S. is averse to long training requirements for its professions — an American cosmetologist has to train for 3000 hours to be certified, which is almost five times as much as a police officer. One might think that handling matters of life, death, and the law would take a little more professionalism than putting on makeup and cutting hair.

Another thing that Europe and Asia do — and which NYC does to some extent — is to have cops stand around on the street instead of driving around or waiting for calls in a station. I wrote about the effectiveness of police boxes and foot patrols back in 2020:

In America, the police mostly drive around, looking for people to pull over and waiting to respond to 911 calls. In Japan, however, lots of police walk around on the street, or stay in police boxes known as koban (交番). And this totally changes the dynamic of police-community interaction!! In Japan, you can (and people often do) ask cops for directions! You can stand around and chat with cops if you like! You can even ask cops for recommendations for local shops and restaurants. And the cops themselves have a totally different experience — instead of only interacting with civilians when something bad is going on, they see thousands upon thousands of people peaceably going about their business, and interact with many of these people…

In the U.S., a cop showing up means that a dangerous, potentially violent confrontation is imminent. In Japan, it’s no big deal — just a person in a uniform standing there, like a security guard in a store…

In addition to creating routine, positive police-community interactions, police can deter crime just by walking around. Experiments with police foot patrols have found that they reduce crime substantially.

There’s plenty more evidence that foot patrols are highly effective in reducing crime.

Note that there’s a strong synergy here between urban density — especially commercial density — and effective policing. If there are a few areas with a lot of foot traffic, it’s easier for cops to stand around and make sure those areas feel safe.

Leftists and many progressives, of course, doggedly oppose all these measures, labeling them “carceral urbanism”. But although I’ve jokingly embraced that label, the reality is that an urbanism that focuses on public safety isn’t really very carceral — it would shift America’s resources from punishing crime to preventing it from happening in the first place. Lewis & Usmani call this a “first world balance”, and it does seem to be what all the countries with nice cities are doing.

Europe, Asia, and NYC get mentally dysfunctional people off the street (and the train)

One thing more people are realizing in the wake of the pandemic is that urban disorder and urban violence are not quite the same thing. Disorder refers to things like public drug use, chaotic street behavior that poses a threat of potential violence, and ubiquitous property crime. No city typifies this distinction more than San Francisco, which has a low-ish murder rate for a U.S. city, but which is awash in visible drug use, petty crime, and scary mentally ill people on the street. Here’s what I wrote back in 2023:

SF has one of the highest property crime rates of any city in the nation. Car break-ins are ubiquitous, and seeing thieves stripping car engines on the street is commonplace. The city has suffered from the same wave of retail smash-and-grab thefts common throughout the Bay Area since 2020. There is a steady drumbeat of stories about thieves ransacking businesses, invading homes, and robbing patrons in cafes.

Now, having your car smashed or your store ransacked or your laptop stolen out of your hands usually doesn’t kill you. Only very rarely do you actually die from that. But it’s a constant reminder that you’re at the mercy of men who could do violence to you if they wanted. If you try to keep hold of your precious laptop, will the thief pull out a knife and slash your throat? If you accidentally catch someone smashing your car window, will they use the baseball bat on your head instead? If you try to protect the merchandise of the store that employs you — on which you depend for your very livelihood — will the thief pull out a gun or a knife? And so on. Property crime is scary because it carries with it the threat of violence.

The second reason is the presence of a lot of loud, aggressive, erratic people on the streets…San Francisco is awash in methamphetamine (which makes people violent and sometimes psychotic) and fentanyl (which is highly addictive, and may cause violence or psychosis upon withdrawal). Signs of these epidemics are everywhere; needles are everywhere on the streets, and drugs themselves are often discovered just sitting around. A number of downtown areas are basically open-air drug markets…

Streets filled with aggressive, screaming strangers and ubiquitous drug markets usually don’t kill you. But they make many people feel unsafe nonetheless. Could the guy who staggers by you bellowing racial slurs be about to beat you…or stab you… Who used the needles lying on the ground in the park where you take your children to play, and will the drugs they used caused them to turn violent? Etc.

San Francisco’s urban chaos is immediately visible to everyone who visits:

It’s true that these problems mostly afflict the downtown area and the Mission district; most of the rest is relatively orderly and nice. But the areas blighted by disorder are the exact same areas that have the greatest density and the most transit stops. This fact has not been lost on the residents of San Francisco’s nicer neighborhoods, who are some of the most NIMBY in the entire nation.

The disorder also afflicts public transit as well. San Francisco’s trains, especially the BART, are notoriously full of disreputable characters, making them a terrifying experience for women, the elderly, and other vulnerable groups. Here’s a pre-pandemic article from SFist that paints a pretty accurate picture:

BART has been lamenting a loss of around 10 million riders on weeknights and weekends over the last five years…[T]he insides of trains are filthy and gross, and people are worried about being robbed or accosted while they ride them…As for petty crime, that seems to be more prevalent during rush hours when thieves can snatch cellphones on crowded trains, dart out of doors and disappear onto crowded platforms. But news reports of violent crimes like one that happened Tuesday night when a man was the victim of an unprovoked attack with a chain, or the fatal stabbing that occurred in the middle of the day last November, are enough to scare anyone from wanting to be trapped on a nighttime or weekend train, especially in Transbay Tube, when someone is having a mental health crisis or is otherwise being threatening.

A pretty clear illustration of the danger of disorder on public transit comes from New York City this week, where a mentally unhinged person burned a sleeping woman to death on the subway. NYC is one of America’s safest big cities, and the murder rate is low. But you should be able to ride the train without being worried that a crazy person will burn you to death if you fall asleep.

There are a number of things American cities can do to curb this urban disorder, if they’re so inclined.

First, note that both Europe and Asia make it much easier to involuntarily commit people with psychiatric disorders to mental institutions. The U.S.’s de-institutionalization movement in the 1960s and 1970s went much further than similar movements in other countries, and the idea that involuntary commitment represents a form of totalitarian state oppression is still a pillar of progressive ideology to this day.

Of course, sometimes, the progressives were right — and still are. Involuntary commitment lends itself to abuses, since mentally ill people are easy to take advantage of. Mental hospitals require constant monitoring to prevent such abuses. But the alternative that America has embraced since the 70s is arguably even less humane — it has condemned many people with severe and dangerous mental illnesses to bounce back and forth between jail and the terrors of the streets.

Involuntary commitment, not conformist culture or racial homogeneity, is the why mentally ill people don’t scream at you on the streets of Tokyo. I have personally witnessed a dangerous mentally ill person being forcibly restrained and committed in Tokyo — it’s not pretty, and I hope there’s oversight to prevent that person from being abused, but it works.

Notably, New York City has tried to fight the post-pandemic wave of urban disorder by stepping up efforts to involuntarily commit people. San Francisco, though, has declined to follow suit. And most cities in America simply ignore the question, since they’re not walkable enough for mentally ill street people to matter much.

As for transit, a key method of keeping it orderly is to simply make people pay for it. Crazy people and petty criminals are often deterred by the small cost of a train or bus fare. Progressives, of course, always push for free public transit; when that doesn’t work, they fight against vigorous enforcement of fare jumping. But this usually spoils the commons that public transit represents — by letting a bunch of crazy people and petty criminals ride for free, it discourages the mass of normal folks who can choose to walk or bike or drive or take Uber. This results in public transit becoming a form of taxpayer-supported welfare instead of a service that most voters use — and this tends to make it vulnerable to budget cuts and disinvestment.

Lo and behold, when some BART stations in the Bay Area put in new ticket gates that are very hard to get past, and added more cops on trains, conditions on the train rapidly improved.

Beyond expanding involuntary commitment and enforcing transit fares, there are a bunch of small things American cities can do to curb disorder — arresting people for selling fentanyl on the street, investigating and imprisoning the smash-and-grab rings that terrorize urban retail outlets, and so on. San Francisco did many of these things in advance of Xi Jinping’s visit to the city for the APEC summit in 2023, and large parts of the downtown area have been noticeably nicer since then (“noticeably nicer” being a relative term, of course). If SF can clean up disorder for the dictator of China, why can’t it do it for its own regular law-abiding taxpaying citizens?

Matt Yglesias also points out that cities in Europe are much more tolerant of ubiquitous security cameras. Cameras are certainly one reason why crime in Japan is so low. In America, the progressives who tend to dominate big-city politics and culture have fought tooth and nail against expanded use of cameras, despite the fact that the chief beneficiaries of those cameras would be poor people of color.

In general, American cities — and to some degree, states — have tried to use anarchy as a form of welfare. By being permissive toward aggressive street behavior, drug use, fare jumping, and petty crime, they have tried to make life more tolerable for poor people. Except it’s primarily poor Americans whose lives are wrecked by the social ills that progressives refuse to crack down on; the middle class and the wealthy can retreat to their car-centric suburbs.

And so American cities are known throughout the world as shitholes, and their residents hide in their houses and drive their cars down highways to the mall instead of taking the train and walking through a nice downtown full of shops. Small-time fentanyl dealers, shoplifters, and unhinged street bullies have a slight measure of freedom, and the regular citizens of America go visit the metropolises of Asia and Europe and wonder what their own country is missing.

These people often get called “homeless”, but in my experience actual homeless people tend to be less disorderly and violent than drugged-up people who already have places to live.

The same seems to be true of housing construction. Some studies find that public housing, or subsidized “affordable” housing, is associated with a small increase in local crime, other studies find no effect. In general, the effect seems to depend a lot on the type of neighborhood where the housing is built, and on the characteristics of the housing itself. These studies are less cut-and-dry than the studies of bus stops and train stations, so I decided to put them in a footnote.

Dems need to treat public safety as a basic human right. No one should have to be in fear of getting attacked.

There's a way that stories really matter in city life -- they don't call them 'urban legends' for nothing. The horrible murder story of tossing a match on a sleeping woman will be repeated as "it's not even safe to fall asleep," you can't count on the kindness of strangers. The stories are about horrors, not kindnesses. I went into Manhattan (from the suburbs) on Saturday by car (not train, because weekend schedules are so limited) and had dinner with a friend who said he was thinking of moving back from London but not after seeing so much vomit (midday!) on the subway. Bottom line -- when the stories are all moving in the same direction of broken social fabric (as they have been in SF for over a decade now) an authority presence is needed that actively shows a mending of the social fabric (one hesitates to say in a Norman Rockwell kind of way). Also take care of your thumb!