Secrets of Japanese urbanism

A review of "Emergent Tokyo", by Jorge Almazán and Studiolab

As it happens, I’m in Japan right now! For those of you who are in Japan, assuming it doesn’t rain, I’ll be doing a hanami party this weekend, so stay tuned for info in case you’d like to join.

Anyway, I thought I’d write a follow-up to my post a couple of weeks ago about Japanese urbanism. Here was the earlier post, which I’ve unpaywalled:

Briefly, I attributed the awesomeness of Japanese cities to:

Zoning that tells you what you can’t build in an area, instead of what you can build, which allows most areas to have shops and restaurants

Zoning that forces shops and restaurants to be smaller in more residential areas

Policies to promote small, independent retail businesses over large ones

Public safety

Noiseproofing and noise ordinances

Excellent trains

Nice public spaces

That list was, of course, pretty reductionist. You could implement those same policies elsewhere in the world, and while you might get a really awesome city, it would still be very different from Tokyo. There’s a huge amount of historical context involved in how Japanese cities became the way they are — events like World War 2, planning choices, cultural preferences and aesthetic style, business and government institutions, broader economic policies, and so on.

A group of authors, led by Jorge Almazán, has written a book that tries to boil down a lot of these historical, institutional, and contingent factors into a few key elements that give Tokyo its distinctive look and feel. That book is called Emergent Tokyo: Designing the Spontaneous City. It’s a short book, filled with pictures and diagrams of Tokyo’s neighborhoods and buildings — which the authors were able to create using the Tokyo city government’s excellent digital records. I highly recommend it; you could easily finish it in a couple of hours, and you’ll walk away with a million thoughts about how the urban spaces around you could be more interesting.

One of the contributors to that book was a friend of mine named Joe McReynolds. He has also written a paper, entitled “Understanding Tokyo's Land Use: The Power of Microspaces”, which is a great companion to Emergent Tokyo, combining the historical insights and architectural analyses of the book with an explanation of the Japanese zoning codes that make it all possible. Both the paper and the book are specific to Tokyo, but much of what they discuss also applies to other Japanese cities like Osaka and Nagoya.

Anyway, I thought I’d talk about some of my takeaways from Emergent Tokyo and from Joe’s paper, and how these insights could be applied to improve other cities in the U.S. and beyond.

Zakkyo buildings

Most of the iconic photos you see of Tokyo involve a whole bunch of colorful densely packed electric signs running up and down the front of narrow buildings. For example:

These are called zakkyo buildings. The word roughly translates to “miscellaneous”. They contain a whole bunch of small retail businesses — restaurants, bars, retail outlets, schools, health care offices, whatever. Sometimes there are dozens of these in a single building. None of the businesses are related to each other; you just rent out a space in a zakkyo.

The distinctive look of a zakkyo building — and from whole streets of zakkyo buildings packed together — comes from Japanese architectural codes. Building tall-ish, narrow buildings was a way to maximize usable floor space within the rules of the postwar period. Japanese laws also allow for a lot of different types of businesses to coexist in any given space — there are basically no regulations on serving alcohol. Some buildings also have external elevators and/or staircases, which makes it easy to get up to a top-floor store from the street.

But perhaps most importantly, Japanese regulations were and are very lenient about allowing a bunch of electric signs, including signs that hang out into the street. Even as Simon and Garfunkel were decrying the “neon god” of urban modernity, Japan was embracing a libertarian approach to small business. Putting a restaurant on the 4th floor of a building often only makes sense if you can inform passing pedestrians that there’s a restaurant up there — which means having a big glowing sign.

Add these all up, and it made economic sense to cram a whole bunch of small businesses into the upper floors of buildings in the city center. So Japan did. And in doing so, it created one of the world’s most distinctive and beautiful modern urban landscapes, even as other cities’ old-fashioned aesthetic preferences caused them to restrict electric signage. Now people come from all over the world to take pictures of Tokyo’s beautiful streetscapes.

But zakkyo buildings have a benefit that goes way beyond aesthetics. When you can stack a bunch of retail businesses vertically, you can cram a whole lot of retail into a very small part of a city. Those retail centers — think of central Shibuya, Shinjuku, etc. — become very crowded with foot traffic.

But that allows more residential areas of the city to be leafy and quiet, even if they’re only a few blocks away! It takes only a few minutes’ walk from the intersection above to reach a quiet backstreet lined with houses.

In dense cities where retail is largely confined to the first floors of buildings, the retail has to be much more spread out throughout the city. This means that if you’re going shopping, you have to walk or take a train long distances in order to see a whole bunch of different stores. It also means that a lot of people’s apartments are located above noisy retail outlets and crowded streets.

In other words, NYC and other dense cities could use some zakkyo buildings. Allow external electric signs and easy street access to top floors, and you allow retail to concentrate vertically instead of having to sprawl across the city. You get the benefit of incredible variety for shoppers, even as you spare a lot of people’s apartment buildings the sounds of tramping feet, shouting voices, delivery trucks, and slamming car doors.

Also, it just looks pretty darn cool.

Pocket neighborhoods

A lot of older Japanese buildings are made of wood, even if they have external facades that make them look like stone or concrete. This is a giant fire hazard, especially in a city like Tokyo where buildings are crammed so closely together. So in order to contain the possible spread of fires, Tokyo created a bunch of large streets fronted by giant concrete buildings, to act as natural firebreaks.

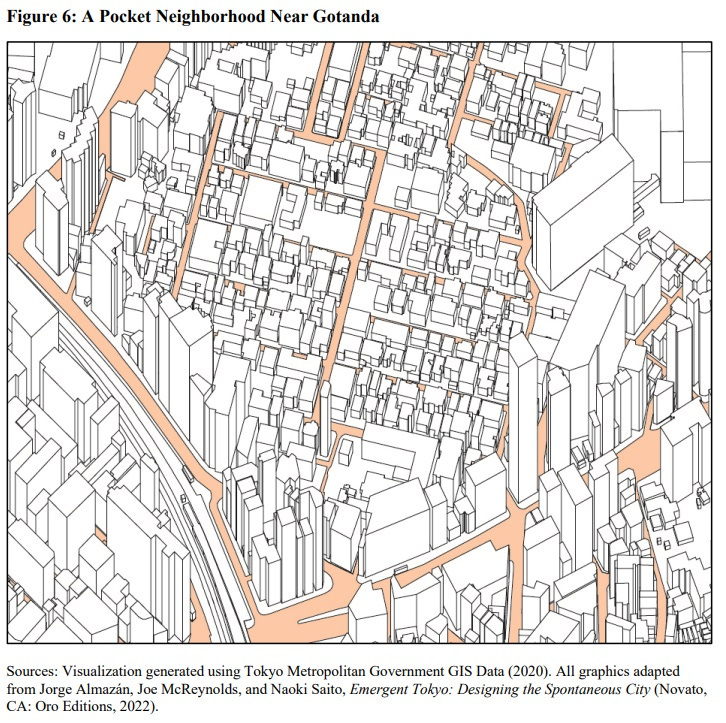

This had a very interesting effect on the urban landscape. It created what Almazán and his coauthors call “pocket” neighborhoods, where a dense maze of small streets and low-rise buildings are shielded by what are basically giant walls. Here’s a diagram of a real neighborhood:

What this means is that if you’re inside the pocket, you don’t run into a lot of cars. Cars still can go inside, into the maze of small streets, but they typically don’t, because it’s almost always easier to just stick to the big streets outside the pocket. So the pocket neighborhoods become very quiet and peaceful, and you can walk around without being afraid of being hit by a car, or having to suck down car exhaust. It cuts down on noise, too.

These pocket neighborhoods achieve what “superblocks” are supposed to achieve, but rarely do. Most real-world “superblocks” are either very small — like Barcelona’s “superilla”, which are lovely, but are really just single blocks — or sterile “tower in the park” monstrosities like in China. Tokyo achieved largely by accident what superblock planners around the world have failed to achieve by design.

These pocket neighborhoods also illustrate a more general feature of Japanese urbanism — the lack of any sort of grid plan. This made navigating Japanese cities by car a pain in the butt before the invention of Google Maps. But it also means that side streets are explicitly for pedestrians first, instead of for cars first. If you’re in a car, you try to stick to the big roads, because otherwise you can easily get lost in an absolute maze of winding side streets. So pedestrians can walk around freely.

In New York City, in contrast, the grid plan means that it’s easy for cars to use small residential streets to get between one big road and the next. So they do. Which means that no matter how small your street is in Manhattan or the inner parts of the boroughs, you can’t really walk in the middle of the street. Which means every street has to have sidewalks, which limits density and reduces public common space for people walking around their neighborhoods. It’s a whole different urban experience. It allows you to achieve the feeling of a low-traffic suburban neighborhood right in the middle of one of the developed world’s densest urban landscapes.

Many big cities’ street plans are now in place, of course — NYC is never going to switch to winding side streets, because that would require massive redevelopment. But if you’re building a new downtown area, in Dallas or Houston or Phoenix or wherever, you might want to consider having a grid plan for the big streets but making winding, looping side streets for people to walk on.

Bottom-up organization

One of Japan’s biggest urbanist strengths, as I wrote in my previous post, is mixed-use neighborhoods. Even residential suburban neighborhoods will have a few businesses scattered around them — a bike shop, a cafe, a neighborhood bar, a little fabric store, and so on. In the U.S., if you want to leave your house and go grab a coffee or a beer or a bite to eat, you generally have to hop in your car, drive somewhere, and park there — or at least use a bicycle. In Japan, you might still bike around or take a train, but if you want to, you can just walk to your neighborhood cafe or bar or noodle shop. Mixed-use zoning creates walkability.

Many Americans would blanch in horror at the thought of a bar or a restaurant or even a shop next to their suburban house. In fact, many Japanese people would feel the same! But in Japan, there are ways for neighborhoods to come together with local businesses and make sure that the character of the neighborhood is preserved. McReynolds writes:

In Tokyo, a disruptive bar next door would also be unwelcome. However, a degree of legal ambiguity is present, which drives neighbors to negotiate a mutually tolerable consensus regarding in-home businesses. Under Tokyo’s zoning regulations…dual-use residences are permitted by right; however, the regulations also prohibit creating an unreasonable nuisance for your neighbors in the process. Local neighborhood associations (自 治会 or jijikai, literally “self-governance association”) will often mediate those disputes between neighbors about what is or isn’t unreasonable; if a consensus can’t be reached, then the adjudicator of last resort will in practice be the local branch of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department…Given the risks and uncertainties that come with summoning police in a dispute, most neighbors prefer to reach consensus among themselves whenever possible.

People who interpret Japan through the lens of tired, outdated stereotypes might see this as a sign of collectivism. In fact, these neighborhood associations are a sign of bottom-up self-organization and a desire to keep out government authorities — a hallmark of Japan’s surprisingly libertarian, bottom-up culture.

I see lots of potential for this kind of bottom-up neighborhood organization in the U.S. A recent article by Anya Martin documents how Houston has been able to build a lot of “missing middle” housing in residential neighborhoods — essentially by giving each micro-neighborhood control over whether to allow density. If American cities adopted Japanese-style mixed-use zoning, they could use similar “neighborhood control” mechanisms to allow neighborhoods to allow restaurants, shops, and even bars, and to choose which ones to allow.

Similarly, Emergent Tokyo documents how many of Japan’s distinctive commercial spaces — the yokocho alleyways, under-track shopping arcades, shotengai covered shopping streets, and even some zakkyo buildings — are protected by small business associations that resist pressure for redevelopment. For example, every tourist who goes to Tokyo loves to go have a drink in Golden Gai, the maze-like area of tiny bars in the back of Shinjuku:

Well, the only reason that Golden Gai still exists, instead of having been bulldozed into a mall long ago, is because all the small businesspeople in the area banded together to resist redevelopment pressure back in the 1980s.

That and many, many other similar episodes demonstrate the usefulness of commercial NIMBYism to create distinctive and interesting city experiences. I spend a lot of time decrying residential NIMBYism for blocking the building of new housing. Residential NIMBYism is bad! But small businesses blocking big businesses, while not economically efficient, can create a positive spillover effect — it lets cities keep their distinctive character, instead of all turning into cookie-cutter versions of one big globalized Standard City. Small business NIMBYism is ultimately one of the reasons tourists flock to Japan.

Which brings me to the biggest thing that Emergent Tokyo leaves out — the centrality of small business protections to Japanese urbanism and Japanese society.

Japan’s secret sauce is small business

Greater Tokyo has 160,000 restaurants. The New York City metropolitan area has 25,000. The Paris metropolitan area has only 13,000. Tokyo has a larger population, but even after accounting for that, it has well over twice the variety of eating establishments that NYC has. Most of these are small businesses rather than big chains. This turns out to be essential not just to Japan’s excellent urbanism, but to Japan’s middle class as well.

Most of Emergent Tokyo is dedicated to discussing Japan’s unique commercial spaces — yokocho, undertrack arcades, and so on. Here are a couple more pictures of those:

For every single one of these cases, the story is the same. The space thrives because of high commercial density — a massive variety of businesses packed into a small area. As I wrote in my previous post, commercial density is massively under-discussed. It allows for variety — in Japan, when you go out to eat, there are a million restaurants to choose from, and they’re all near each other. When you go clothes shopping, there are a million little boutiques to try, and they’re all near each other. This massively enhances the shopping experience.

But it’s not just variety; it’s uniqueness. If you went into a zakkyo building and everything was just an Olive Garden, a Starbucks, or a 24 Hour Fitness, it would get pretty boring after a while. The romance of urban Japan is that there are always a bunch of completely new places to discover, and so it’s always worth walking around and discovering stuff.

And that couldn’t happen unless there were a huge number of people who wanted to start small businesses. Every single commercial space that Emergent Tokyo talks about — the yokocho, the zakkyo, the undertrack arcades — depends on a bunch of small businesses wanting to locate there. If that demand isn’t there, the spaces will either go unfilled or be filled by chains. And without the small business associations to band together and resist redevelopment pressures, Japan’s most iconic urban spaces will eventually be turned into boring corporate malls — not because of the disembodied evils of capitalism, but simply because without small businesses, there’s not much to do with that space except put a boring corporate mall there.

What Emergent Tokyo never delves into is why Japan is so small-business-centric. Part of it is driven by policy — Japan has a number of government policies in place to support small retail businesses over large one. One of these is the Large Store Law, which discourages big stores in dense urban areas. But there are many others. There is a vast and diverse array of subsidies and supports targeted specifically at small retail businesses — startup cost assistance, renovation assistance, low-interest loans, tax incentives, training for small business entrepreneurs, community preservation laws, and so on. Americans are often astonished when they find out just how easy it is to open up a small retail business in Japan:

Besides making urban environments pleasant and exciting, it seems to me that small business owners provide a crucial constituency for many of the essential ingredients of Japanese urbanism.

For example, take public safety. When a chain store gets looted, the company doesn’t close down; its large network of stores can absorb the losses. But when a small independent store gets looted, it’s often ruinous for the owner. Small businesspeople therefore have an interest in policies that promote public safety, which is one of the key elements of Japan’s excellent cities.

Another example is walkability. Chains have name recognition and marketing budgets; small independent restaurants and stores in urban areas depend more on serendipitous foot traffic. So it’s in the interests of small businesspeople to have great trains, walkable spaces, and residential density, in order to get them more customers. When people ask why Japan has the world’s best train system, the political power of small business is rarely mentioned, but it seems like a factor worth exploring.

And small businesses create the ultimate constituency for capitalism itself. Centrally planned economies rarely have the kind of spontaneous, vibrant commercial spaces described so lovingly in Emergent Tokyo. Small business turns a large mass of the middle class into capitalists, giving them a direct stake in the system of private business ownership. They strongly tend to vote for pro-business parties.

In the U.S., small “mom-and-pop” retail businesses have been disappearing since the middle of the 20th century, as large chains used their higher productivity to price them out of business. Japan has stubbornly fought against this trend, and this is one thing that has allowed its cities to be more vibrant and sustain greater commercial variety than America’s. There’s a cost in terms of efficiency, but cheap stuff isn’t the only enjoyable thing in this world.

Big U.S. cities can change this if they want to. There’s already a movement to restrict chain stores in city centers, but it needs to be paired with measures to encourage, train, and support small independent retail businesses. Zoning reform has to be a part of this, and regulations like permitting requirements and limitations on liquor licenses and electric signs should be loosened. And of course walkability, transit, and public safety will all need to be improved if this is going to work. If cities can bring themselves to do all these things, I think they can create, if not a replica of the Japanese urban experience, then at least something a lot more in that direction than what exists now.

In fact, small businesses are now under threat in Japan, due to a lack of young people who want to take over family businesses. This is a big reason why bland corporate malls are now a bigger part of Japan’s shopping experience than they were two or three decades ago. But as Emergent Tokyo notes, there still are quite a few young Japanese people who want to start new small retail businesses, so hopefully this will be enough to sustain the kind of Japanese urbanism that the rest of the world has come to know and love.

Good essay! I think small business centrism and mixed use zoning is the default almost everywhere except the US. I've had he same in India, Singapore, much of Europe, seasia and more. The idea of having open regs on opening a shop or whatever, with the neighbours right to complain, creates a pretty nice equilibrium.

I find the zoned corporate strip malls to be the odd one out, the results of a rather weird policy choice.

There are many plus points to Japan's urban development but I think it is worth pointing out that there are tradeoffs (note that I live in Japan and have no plans to not remain in Japan).

First is the danger in a major earthquake etc. All of the Zakkyo, Yokocho etc. are likely to fare very badly when a fire breaks out. Being on, say, the 8th floor of a narrow tower when the fifth floor is on fire and there are (as would likely be the case after a quake) fires all over the place is liable to be fatal. And we know what happens to a Yokocho because there was one that burned to the ground after the Noto Earthquake earlier this year. Luckily the whole place was shut for the NY Day holiday but if the quake had occurred say a couple of days earlier and later at night I imagine there would have been considerable loss of life.

Second the fact that neighborhood associations prefer to not get the police/justice system involved in local disputes is not actually a positive thing for the police. What it says is that the police are arbitrary and capricious and you have no way to predict how they will rule. This is, BTW, one reason I believe rape is severely under-reported in Japan. Japanese rape victims well-founded fears that the cops will take the side of the rapist. The same may well apply to a lot of other crime. The police have a 99% successful conviction rate but I wouldn't assume that means they have a 99% accuracy rate.

Thirdly those neighborhood associations are very much a mixed bunch. Some are good. Some make the worst US Home Owner Associations seem like bastions of tolerant local democracy.

I think on the whole Japan does things well but there's a lot of dark underbelly that visitors don't always notice.