Don't expect too much from the U.S.-China detente

A thaw is in the air, but Chimerica isn't coming back.

The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit this week has taken over San Francisco, with travelers flooding into town from all over the world. A massive police presence has been deployed to rid the downtown area of its usual chaotic mix of petty crime and visible homelessness, in order to make SF look nice for the visiting dignitaries. (Locals are questioning why this doesn’t happen all year round, but that’s a topic for another post.) The city has come to life, with a mix of pageantry, parties, and protests — the latter mostly against Xi Jinping, who is here in town for the summit.

APEC is a discussion forum, where political and business leaders come to talk with each other and to announce deals and initiatives and so on. Lots of important things are happening here. But by far the most important — and the thing that everyone is talking about — is the detente between the U.S. and China. Xi and Biden are actually going to meet face to face on Wednesday, and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen will meet with China’s Vice Premier He Lifeng. The two countries are expected to announce a series of cooperative initiatives, including a joint effort to crack down on the fentanyl trade and the reopening of military-to-military communications.

This is actually the culmination of a trend that has been going on for a few months now. Yellen visited China this summer. National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan downplayed the idea of “decoupling” in April, and said in May that the U.S. wants to “move beyond” the spy balloon incident. And Charles Brown, the U.S. top general, recently said that he doesn’t think China wants to take Taiwan by force. California Governor Gavin Newsom, meanwhile, recently went to China to talk up cooperation on climate change.

China, for its part, has taken a milder tone toward the U.S. recently after years of aggressive “wolf warrior” rhetoric. In June, Xi promised to protect foreign investors. And China recently paid its respects to the Flying Tigers, a U.S. military effort to help China’s Nationalists resist the Japanese Empire in World War 2.

It’s fair to say that the U.S. and China have now entered a period of detente in the protracted rivalry that I’ve been calling Cold War 2. These lulls were fairly common in Cold War 1, especially in the 60s and 70s. In general, they’re a good sign, because they define the difference between a cold war and the leadup to a hot one — detente basically signals that two rivals expect to manage their competition on an ongoing basis instead of believing that they have to fight it out. A war might still break out, of course, but it’s good to see both countries preparing for the possibility of peace.

So anyway, since I’ve been writing a lot about Cold War 2 over the past year, I thought I’d talk a bit about this detente — why it’s happening, and how much constructive cooperation we can actually expect from it.

Why the U.S. and China are having a moment of detente

One obvious reason for the U.S.-China thaw is that a war between the two countries would be incredibly terrible and destructive. Xi Jinping may yet decide that it’s worth the risk and cost of a world war, but if so, he’ll do so at a time of his own choosing, rather than letting events force him inevitably into a confrontation.

But I think there are a few more factors at work here. On the U.S. side, two of those are China’s economic slowdown and the war in Gaza.

China is experiencing a protracted economic slowdown, caused by the combination of the end of catch-up growth and a major bust in the real estate sector. Officially the country is still growing at around 5%, but A) that’s a year-over-year number that’s inflated by a comparison to the baseline of Zero Covid in 2022, and B) China often smooths its economic numbers to make downturns look milder. Various statistics show continued weakening of economic activity, despite the ramping up of stimulus measures. And there’s every sign that the real estate crisis, which is the fundamental driver of the slowdown, is far from over.

I’ve argued that long-term economic weakness increases the economic incentive for China to go to war, since A) it decreases the opportunity costs from war, and B) military production is powerful stimulus. But from the perspective of the Biden administration, China’s economic weakness probably means that it seems like less of an imminent threat. Jake Sullivan and other Biden advisors are keenly aware that economic power translates into military power, and so the fact that China will now have a bit less economic power five or ten years down the line makes it feel a bit less threatening.

Meanwhile, the Biden administration has its hands full elsewhere. The war in Gaza is sucking up everyone’s attention, and the Ukraine war is still slogging on. Meanwhile at home, an election is looming; if Trump is reelected, the nation’s entire strategic posture will be thrown into disarray, and it might collapse into domestic conflict. With all of those looming threats, and China’s economy in the dumps, saying nice things to China and pivoting to the Middle East and to the domestic front probably seems like a wise strategic move — especially if it helps the U.S. look like a peaceful promoter of the status quo in Asia.

It’s possible, of course, that this is a mistake. I’ve argued that Asia is far more important to U.S. interests than the Middle East (or even Europe). And as Greg Ip notes in a recent column, China’s economic slowdown doesn’t really make it less of a military threat:

[W]hile as much as three-quarters of China’s economy faces headwinds, the quarter that doesn’t, manufacturing, will keep China an economic and military threat to the West for the foreseeable future—even if overall growth turns lackluster…

China’s manufacturing prowess will persist because of baked-in competitive advantages: a large, integrated and adaptive base of producers, a reliable and modestly paid workforce and management know-how…China’s manufacturing prowess is also a formidable military asset. Its gigantic and modernized shipyards already build 46% of the world’s ships, enabling it to churn out several new warships and submarines a year. By contrast the U.S. shipbuilding industry, despite a century of protection, has less than 1% of world capacity…

Dan Wang, a visiting scholar at Yale Law School’s Tsai China Center who has written extensively on China’s technology industry, said the U.S. leads mainly in knowledge-intensive technologies such as artificial intelligence and biotech rather than physical products. “Imagine a future scenario in which these countries are in serious conflict and trade stops, who do you want to bet on: the country with all the large language models and biotech and business software, or the country with large and adaptive manufacturing base? My money would be on the latter.”

So complacency about Chinese power would be very foolish. But fixing the disparities that Ip talks about will take a lot of time and persistent effort across a wide array of sectors — defense production, reshoring, friend-shoring, industrial policy, and so on. It doesn’t necessarily help the U.S. to be bellicose toward China at this moment, especially when China’s neighbors are already eager to get closer to the U.S. So Biden might be making exactly the right move here.

On China’s side, the motives for detente are harder to guess at. Xi Jinping’s domestic political position looks perfectly secure from the outside, but this could be at least partly a facade. A recent poll found that the Chinese public is much less hostile toward the U.S. than they were a year ago, which could somehow reflect the official Party line, but could also be a sign that Chinese people are unhappy with Xi over the slowing economy.

Another reason for China’s leaders to seek detente might be if U.S. export controls are hurting more than they let on. China’s top chipmaker, SMIC, saw an 80% drop in its profits last quarter.

Of course, a big story recently was that China produced a 7nm chip called the Kirin 9000S, which lots of people took as evidence that export controls have failed. But the chip was produced using old technology, and many experts think China will only be able to able to produce the chip in large volumes at great expense. It may be that the Kirin 9000S was a sort of Potemkin project to create the illusion that export controls are ineffectual, in order to pressure the U.S. to drop them just as they started to actually have an effect.

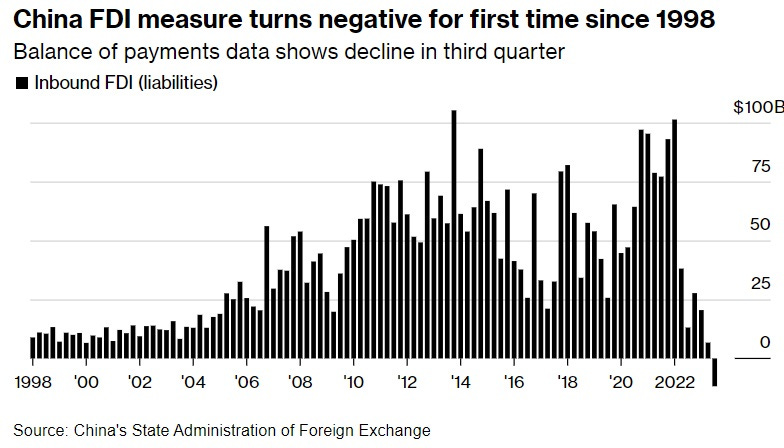

China is also seeing it’s first drop in foreign direct investment in many years:

Economists have said the decline in FDI…reflects less willingness by foreign companies to re-invest profits made in China in the country…

“Probably this reflects foreign firms repatriating earnings from China, whereas previously they reinvested them,” said Duncan Wrigley, chief China economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics. “International firms, especially US ones, have been reconfiguring supply chains to use alternatives to China.”

And overseas portfolio investment in Chinese stocks and bonds is also in reverse, which could make it harder for the government to bail out the real estate sector.

So Xi might want to make soothing noises toward the U.S. in order to stem the tide of disinvestment. If American companies can be lulled into thinking that the period of tension is over and “Chimerica” is back on track, maybe FDI might resume. And if asset managers in the West think China is “investable” again, it might help bail out Chinese banks and local governments a bit.

So my guess is that both sides see a detente as in their interests for the moment, whether they’re right or not. The U.S. needs to focus on other threats for a while, and China needs to focus on its economy. But there are several reasons to believe that this moment of decreased tension won’t lead to the end of Cold War 2 or the resumption of Chimerica.

Don’t expect too much from this detente

First, let’s talk about the economic situation. APEC will doubtless feature some business leaders pledging to invest in China, but the rhetoric will likely exceed the reality.

For one thing, just look at the timing of the FDI outflow in the third quarter. Xi’s wheedling of foreign investors was all the way back in June, and followed similar efforts by his deputy Li Qiang back in March. But that wasn’t enough to move the needle on companies’ decisions. One reason is that the government’s actions — continued harassment of Western companies — have belied its words. This is from just a few weeks ago:

Chinese authorities are again shaking the confidence of foreign companies in the country with a series of arrests across industries and an investigation into Foxconn Technology Group, Apple Inc.’s most important partner…Meanwhile, an executive and two former employees of WPP Plc, one of the world’s biggest advertising companies, have been detained in China…The government detained a local employee of a Japanese metals trading company in March…And this month, a court formally charged an Astellas Pharma Inc. executive on suspicion of espionage.

That’s not the kind of environment that screams “open for business”. Many Western business executives have stopped traveling to China, fearing arbitrary detention.

And even if detente has reduced the actual threat of war, at least for the time being, Western companies are probably still becoming more aware of the baseline threat. And that risk is considerable. Even though General Brown said China doesn’t want to invade Taiwan, the People’s Liberation Army has massively stepped up military pressure on the island and on U.S. forces nearby:

[T]he Chinese military has conducted more than 180 risky intercepts against U.S. surveillance aircraft in the Pacific in the past two years, more than in the previous decade…

Fighter jets that once stayed on China’s side of the Taiwan Strait have been crossing the median line…with greater frequency…On Sept. 17, a record 103 Chinese warplanes flew near Taiwanese airspace in a 24-hour period…China sent a drone all the way around Taiwan for the first time in April, and this has quickly become a regular maneuver…Chinese aircraft carriers are making themselves at home on the other side of the island, in the Pacific Ocean…There, they launch jets at Taiwan’s east coast and practice repelling the United States should it one day come to defend Taiwan from a Chinese invasion.

The September drills were the largest in the waters to Taiwan’s east for nearly a decade, with 17 warships including the Shandong aircraft carrier holding large-scale exercises stretching from the Philippines Sea to near the American territory of Guam.

Check out that story in the Washington Post if you want to see some scary maps of Chinese fleet maneuvers. Meanwhile, the U.S. is holding large-scale war games in the region to prepare for an invasion scenario.

And Taiwan isn’t the only flashpoint. China and the Philippines are engaging in a constant low-level struggle over disputed waters and reefs, with China regularly harassing Philippine boats and sending warships into Philippine waters. Biden has firmly promised to help defend the Philippines, which is its treaty ally, from Chinese attack.

Executives of multinational companies know that the day that a U.S.-China war begins, their investments in China will probably vaporize. That’s existential risk for any company that depends on China for its continued operation. And unless you’re extremely skilled at sticking your head in the sand, existential risk isn’t the kind of thing that can be lulled away by an APEC summit or a few soothing statements.

This, fundamentally, is why companies are pulling money and operations out of the country. They’ll still produce things in China for the Chinese market, of course — since that market would also dry up in the event of a war, keeping domestic-focused production in the country entails little or no additional risk. But the effort to move at least some supply chains entirely out of China is unlikely to halt. Chimerica isn’t coming back. (And note that this has very little to do with how much the two countries trade with each other.)

All this, of course, is on top of the political incentives to decouple. The U.S. public’s opinion of China is at a record low; in addition to persistent human rights concerns and fears of Chinese expansionism, the idea that China took advantage of U.S. goodwill in the 2000s and early 2010s to devastate U.S. industry and the American working class is now deeply entrenched on both sides of the aisle. This means that Biden will be punished at the polls if he appears too soft on China. (Ironically, Trump could probably get away with being much more conciliatory toward Xi, because he would be insulated by his reputation as tough on China.)

Diplomatically, I also don’t expect much from the detente. Restoring military-to-military communications is the exception here — this is very good and important, since it reduces the risk of a miscalculation or miscommunication that leads to an accidental war. But the other agreements that the U.S. is making with China, or seeking to make, seem unlikely to go anywhere.

The reason is that China has a history of saying one thing and doing another, especially under Xi. China promised to let Hong Kong keep its political system for 50 years; that pledge was broken in 2020. Xi promised not to militarize the South China Sea back in 2015; he has now militarized it. Amnesty International has documented China’s broken promises on human rights. The country hasn’t even come close to meeting its pledges on climate change, building vast amounts of new coal plants. Promises that China would open up its agricultural and digital markets to European companies were never kept. When Donald Trump launched a trade war on China, the leadership promised to buy $200 billion of American goods; it didn’t buy them. And so on, and so forth.

The pattern should be abundantly clear. Xi Jinping and the Chinese leadership talk big, make expansive promises, get some good press, and then simply do whatever they were going to do anyway.

The agreement over fentanyl is likely to go the same way. Selling the chemical components to make the deadly drug makes Chinese companies some money, and American consumption of the drug weakens the U.S. by straining the medical system and making the population less healthy. Curbing fentanyl would cost money and effort, and it wouldn’t serve Xi’s goals of sustaining the economy while weakening his most powerful rival. Therefore I predict he will talk about it, but will not do it.

Climate change is much the same. Of course China will continue to produce tons of solar panels, batteries, and electric vehicles, and to sell these to the world, because it’s in its economic interest to do so. But closing down existing coal plants would represent a big blow to a politically powerful industry, at a time when Xi is already looking incompetent for cracking down on real estate, IT, finance, and education. Even if building new solar would be a little bit cheaper than operating those existing coal plants in the long run, it would require lots of up-front costs, displace lots of workers from their existing jobs, require many factories that depend on coal inputs to retool, and deprive many local CCP members of their personal fortunes. In other words, the risks to Xi Jinping of taking bold action on climate change probably vastly outweigh the benefits; thus, I predict he will talk about it, but will not do it, no matter how many photo-ops Newsom gets.

To sum up, I think the period of detente now unfolding between the U.S. and China is a good thing, because it reduces the risk of accidental war. But other than that, I don’t expect much to change on the economic or diplomatic fronts. The breakup of Chimerica is being driven by vast, slow-moving forces, and some chats and handshakes aren’t going to do much to alter that fundamental dynamic.

I love that China is investing in carrier navy tech right at the end of the carrier era. It's exactly like Imperial Japan being obsessed with having the best battleships at the time when battleships has become obsolete.

Re: climate change. China built more wind and solar in the first 9 months of 2023 (415 TWh) than *the sum total* of every nuclear plant under construction (408 TWh). And yes, these numbers have already been adjusted for capacity factor. As a result, China's CO2 output is expected to begin a structural decline as soon as next year [1]. Simultaneously, China has launched a new plan to pay coal operators to operate at < 50% capacity, with the majority of their revenue coming from these payments by the later part of this decade [2]. They're also hugely ramping up on battery production.

I don't want to seem overly optimistic here -- they're still going to be emitting a lot of CO2, but I think "China isn't going to do anything about climate change" might actually be wrong in this case. It's also not hard to notice that these massive buildouts will do a lot to secure the country's energy supply in the event of a major Pacific war.

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/business/2023/nov/13/chinas-carbon-emissions-set-for-structural-decline-from-next-year

[2] https://twitter.com/pretentiouswhat/status/1722886066942743017?s=12&t=sPOl9bVNdjREujwiUeFx1g