The end of the system of the world

A critical point has been reached; decoupling is for real this time.

This is a big-think, “sweeping overview” sort of post. I find myself writing more of these recently, not because there aren’t little interesting news items or econ papers or debates to focus on, but because big things are happening very fast in the world right now, and I want to try and keep track of them.

The system of the world, 2001-2021

After the end of the Cold War, the United States forged a new world. The driving, animating idea behind this new world was the belief that global trade integration would restrain international conflict. At first this rested on a Fukuyama-type “end of history” theory that political and economic liberalization would follow globalization, but as it became clear that various bureaucratic one-party oligarchies and petrostates (most notably China and Russia) were resistant to the end of history, the hopes for trade became more modest — at least countries that depended on each other economically would not fall into active conflict.

We didn’t just pay lip service to this theory; we bet the entire world on it. The U.S. and Europe championed the admission of China into the World Trade Organization, and deliberately looked the other way on a number of things that might have given us reason to restrict trade with China (currency manipulation in the 00s, various mercantilist policies, poor labor and environmental standards). As a result, the global economy underwent a titanic shift. Whereas global manufacturing, trading networks, and supply chains had once been dominated by the U.S., Japan, and Germany, China now came to occupy the central place in all of these:

As of 2021, China’s manufacturing output was equal to that of the U.S. and all of Europe combined.

There were were always those who fretted about this shift, but too many people were just making too much money from it to upset the apple cart. U.S. manufacturers boosted their profits — and at least on paper, their productivity — by outsourcing production to China, while retail outlets (and consumers) benefitted from a flood of cheap imports. American companies grew their profits massively from grabbing mere slivers of the vast Chinese market, and salivated over the possibility of more. The finance industry reaped the benefits of cheap capital inflows as China bought U.S. assets in order to hold down the value of the RMB in the 2000s. Knowledge workers in the U.S. and Europe benefitted from researching, designing, and marketing the products that China built for us. Production workers in rich countries lost out big-time, but this was a price our country was willing to pay. America and our rich-world allies went from being the world’s workshop to being the world’s research park, and the people who had been our factory workers became the janitors and cooks and security guards of that research park.

This new system meant big compromises for China’s ruling elite as well. For decades they had closed off their society from foreign influences in an attempt to reorder it according to their liking, and opening up to global trade meant relinquishing some of the social control they had fought so hard for. An economy based on foreign direct investment meant a loss of economic control to foreign corporations. And occupying the low-value middle of the global supply chain — the assembly, processing, and packaging that requires enormous mobilization of resources but yields only modest profit margins — put China in danger of falling into the dreaded “middle income trap”.

But China was simply growing too fast to break this deal. Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao held firmly to the course Deng Xiaoping — who hand-picked them as his successors — had laid out for them. Economically, China pursued “reform and opening up”, while militarily and diplomatically it chose to “hide its strength and bide its time”.

Some called the world system of the 2000s and early 2010s “Chimerica”. During these years, the hope that global trade would lead to a cessation of great-power conflict, even without ideological alignment, seemed justified. And although China’s politics didn’t liberalize, under Jiang and Hu the country became more open to foreign travelers, foreign workers, and foreign ideas. This might not have been the End of History, but it was a compromise most people could live with for a while.

Strains in the world-system

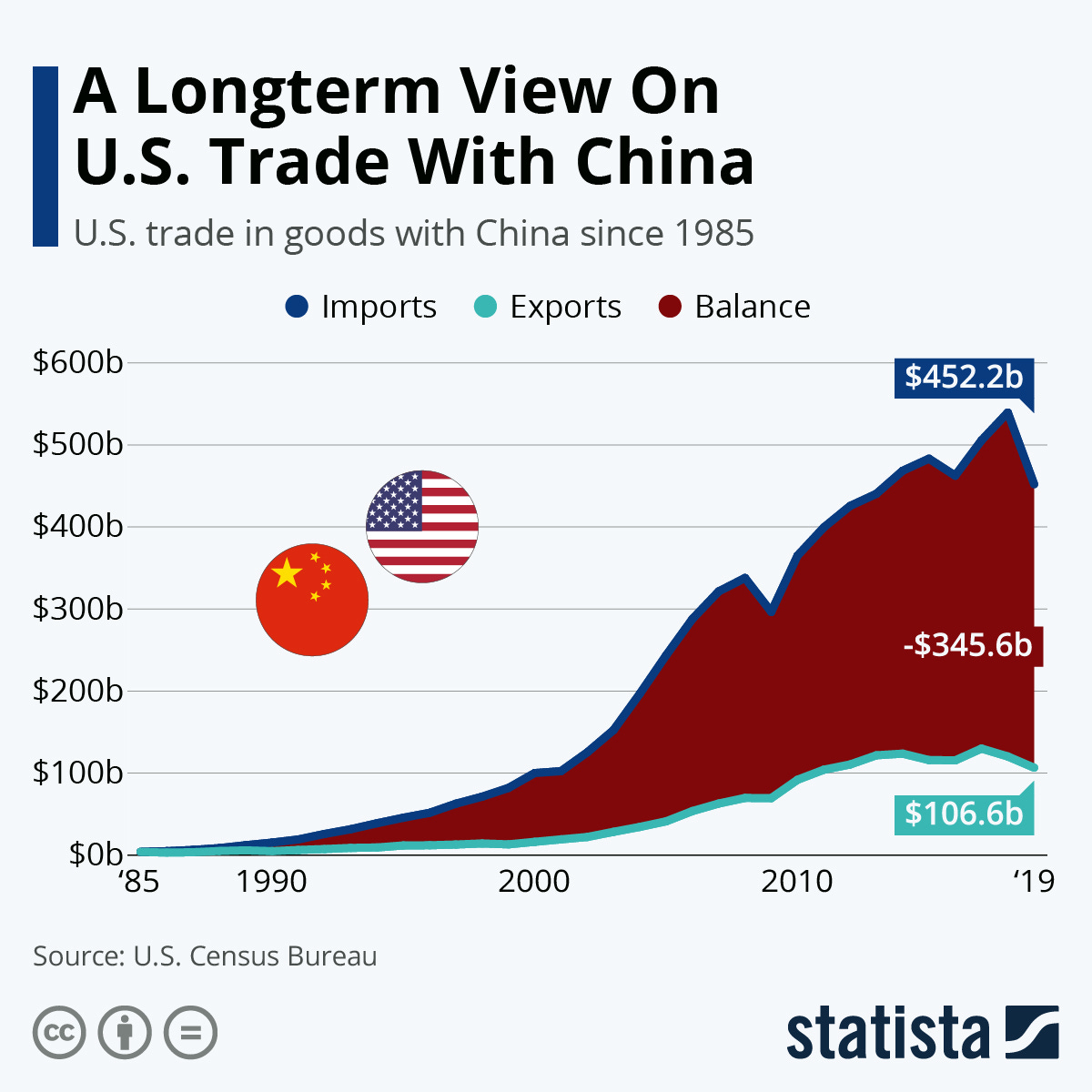

In the mid-2010s, this compromise began to break down. On the U.S. side, there was increasing anger over the long-term decline of good manufacturing jobs, and an increasing feeling of the U.S. in second place. China, and the Chimerica system, became the target of some of this anger — not without good reason. An increasingly thin, fraying elite consensus in favor of the system snapped when Donald Trump came to power. Trump slapped tariffs on China that raised prices slightly for U.S. consumers and manufacturers, but hurt China’s economy considerably more. The U.S. began to scrutinize and block Chinese investment a lot more under CFIUS, while export controls were put in place to strangle China’s flagship electronics company Huawei. U.S. imports from China shrank, eroding the bilateral trade deficit a bit:

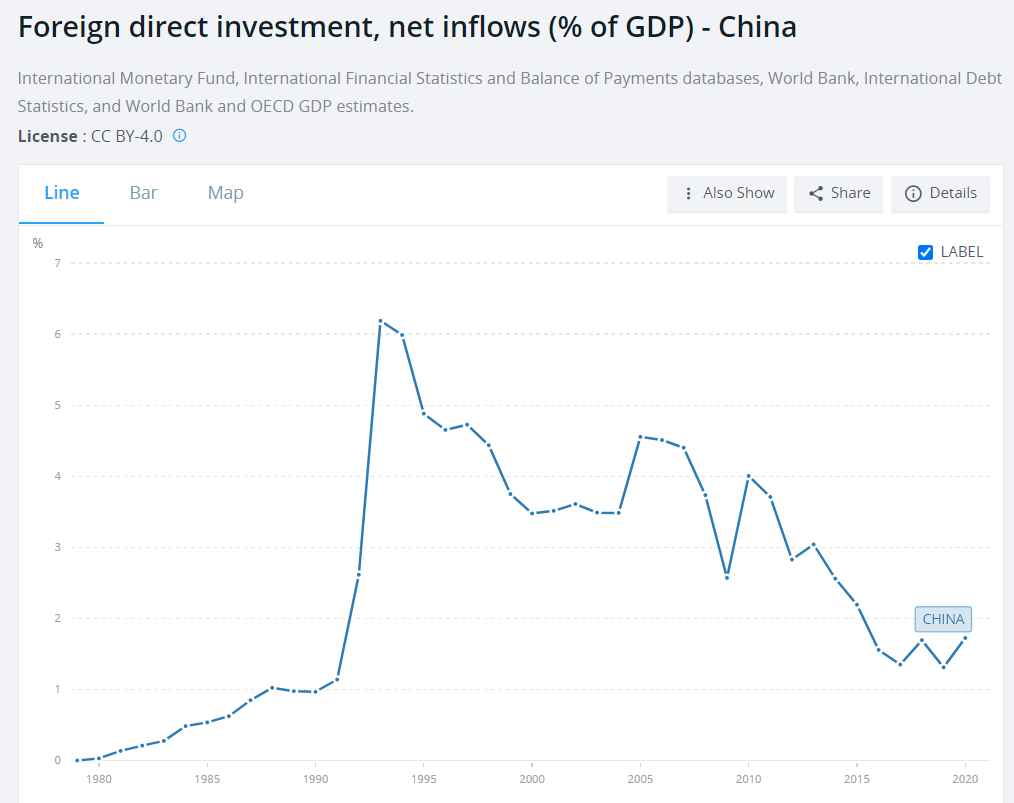

Meanwhile, in China, Xi Jinping initiated a program to onshore the production of high-value intermediate goods, even as rising labor costs started to force some low-value labor-intensive assembly work to places like Vietnam or Bangladesh. Xi also shifted China’s industrial policy from a regional patchwork to a unified national effort. Foreign direct investment as a percent of China’s economy dropped under Xi:

As Bloomberg’s David Fickling reports, trade became a smaller portion of China’s economy over this period:

And yet Chimerica would not be defeated so easily. U.S. imports from China, and the bilateral trade deficit, rebounded strongly in 2020-21 as a result of the Covid pandemic. The U.S. failed to increase manufacturing production at all under Trump, even as the economy grew quickly.

Meanwhile, despite an eroding cost advantage, China’s share of global manufacturing grew relentlessly:

U.S., European, and Asian companies were investing in China at a slightly slower rate, but this is partly because they had already moved so much of their production there. The country’s eroding cost advantage was more than cancelled out by the desire to grab a slightly larger sliver of the vast and growing Chinese market, the need to have factories located close to suppliers, and the country’s vast pool of well-trained process engineers — forces that economists collectively refer to as agglomeration effects. And rising costs and increasing government harassment and IP theft didn’t really make multinationals think about divesting; by the late 2010s, companies had simply become used to the idea that their manufacturing would be sourced from China. Making things in China was push-button, it was a no-brainer, it wasn’t something where you got out the Excel spreadsheet to figure out if it penciled. China was simply the “make-everything country”, so that is where you made things.

In other words, the vast and inevitable forces of economic agglomeration continued to dictate that China should be the world’s workshop and America (and Europe and Japan) its research park. But there is one force in the global economy more powerful even than agglomeration: Great-power conflict.

The rupture

In 2020 and 2021, a number of events convinced China’s leaders (and many observers in the U.S. and around the world) that China’s system had surpassed the U.S. in terms of economic vitality, political stability, and comprehensive national power. Most of these events were connected to the Covid pandemic. China’s ability to make simple goods like masks and Covid tests, coupled with the U.S.’ struggles in making these things, seemed to validate China’s positioning in the global supply chain. China’s ability to suppress the virus with non-pharmaceutical interventions seemed to demonstrate its higher state capacity. And U.S. unrest in 2020 and early 2021 seemed to suggest a society that was too internally divided to continue to play a central role on the world stage.

Xi Jinping, China’s leader, apparently felt that these events validated his pre-existing plan for “great changes unseen in a century” — i.e. China’s displacement of the U.S. as the global hegemon. Though this was Xi’s ambition from the start, it was the Chimerica system that had made his dream feasible, by making China the biggest manufacturing and trading nation on Earth.

Now, Xi seemed to feel that China had extracted all it could from the Chimerica system, and that the benefits no longer outweighed the costs. His industrial crackdowns in 2021 included measures to limit Western, Japanese, and South Korean cultural influences. Under his Zero Covid system, China became much more closed to the world, with inflows of people from abroad basically halted.

But these were only the first of a number of ways in which Xi, who just cemented his absolute power over his country at the 20th Party Congress, has made it clear that China’s era of “reform and opening up” is over. Here are some excerpts from an interview with Joerg Wuttke, President of the EU Chamber of Commerce in China about what the changes at the party congress mean:

The reformers have been totally cut off…[T]he opening up of the Chinese economy is not going to continue…We have to get away from the idea that China’s policy is still basically tailored to economic growth…Many observers have thought until today that although the Party calls itself Communist, it is basically pursuing a form of Manchester Capitalism. That is over…

China’s foreign policy will become even more assertive and confrontational. Xi used the word “struggle” seventeen times in his speech to the Party Congress, twelve times in an international context, mostly directed at the USA. China wants to be unassailable and more self-sufficient, it wants to fight for future markets and technologies. In this context, the term struggle also has an absolute claim: There are only winners and losers…The Party leadership shows a similar self-confidence as Germany at the beginning of the 20th century.

Wuttke has every incentive to say that China is still oriented toward economic growth and that the China business environment is still attractive for multinational companies. And yet he is saying the opposite. I tend to believe him. There are a ton of evidence that Xi’s regime is de-prioritizing the foreign businesses whose investment helped build China up to where it is today. As just one example, China’s real estate developers look likely to soak their foreign creditors first:

Another small sign is that China has stopped publishing most of its economic statistics — numbers that foreign companies rely on as justification for their decision to invest in the Chinese market.

Meanwhile, China’s soft support for Russia’s Ukraine invasion and its increasingly aggressive posture toward Taiwan have prompted the Biden administration to pull out the big guns. Sweeping export controls on the semiconductor industry — covering not just chips, but also chipmaking tools and personnel — represent a zero-sum lunge for the jugular of China’s technological ambitions. For in-depth coverage of just how big a deal this is, I recommend Chris Miller’s recent interview on the Odd Lots podcast. And those export controls may soon be expanded to other technologies:

(A transcript can be found here. And here is a post by Ben Thompson that goes into even greater detail.)

This makes perfect sense if you view national security and defense as core to U.S. policymaking. The U.S. was willing to tolerate the devastation of its manufacturing base, but not its relegation to a second-class power. In other words, whereas during the Chimerica era both countries prioritized the mutual economic benefits they could get from a symbiotic relationship, they now prioritize the zero-sum military and geopolitical competition to which economics are a key input.

Markets, for their part, seem to realize that this time is different. China’s stocks cratered after the party congress — so much so that they’re now trading below the value of their assets on paper.

China’s wealthier citizens also seem to realize that the era of economic focus is over; many are making plans to flee the country.

The key thing to understand about this decoupling, I think, and the reason it’s for real, is that this is something the leaders of both the U.S. and China want. No matter what you heard in 2018, this is not a case of a protectionist U.S. trying to defend its manufacturing industries while China becomes the champion of globalism. The U.S. is acting not out of concern for its industries — indeed, its chip industry will take a huge hit from export controls — but because of how it perceives its own national security. And China’s leaders want to shift to indigenous industry, regulated industry, and even nationalized industry, even if that shift makes China grow more slowly.

The decoupling between China and the developed democracies, so long a topic of conversation and speculation, now appears to be a reality. A critical point has been reached. The old world-economic system of Chimerica is being swept away, and something new will take its place.

The new world system

It will take a while for the new world-economic system to be born (and as Gramsci says, this will be a “time of monsters”). A lot will be contingent on events, such as whether there is another world war. But already I think we can make some educated guesses and ask some key questions.

One reasonable prediction is that the era of global value chains will not come to an end. Offshoring and supply chaining are just how companies know how to produce stuff now, meaning that — barring a very catastrophic war — we will not go back to an era of largely self-contained national manufacturing economies. Instead, supply chains will shift into blocs. China is obviously one bloc; Xi and his followers want China to make and own everything valuable in-house and rely on other countries only for raw materials and other low-value goods. In the absence of the U.S.-led liberal world order to enforce free trade, securing those resources will require geopolitical and even military action — a return, in some form or another, to the pre-WW2 era that will doubtless draw at least scattered protests of neo-imperialism. There will be struggles over the resources of some neutral countries, including poor countries, and this could turn into some ugly Cold-War style proxy struggles.

The second bloc is less certain. I expect the Biden administration and/or its successor to get tripped up for a while by the mirage of a self-sufficient U.S., and to implement “Buy American” policies that hurt our allies and trading partners and slow the formation of a bloc that can match China. But if Americans can finally pull their heads out of their rear ends and recognize that their country doesn’t dominate the world the way it used to, there’s a chance to create a non-China economic bloc that preserves lots of the efficiencies of the old Chimerica system while also serving U.S. national security needs.

That bloc would not only include America’s formal allies or the developed democracies; instead it would include lots of developing countries that would like to hedge against Chinese power and secure access to rich-world markets. Two prime examples are India and Vietnam. I noted a recent article in The Economist about how Apple — the poster child for American investment in China — is starting to shift production to those countries:

Apple banked on China-based factories, which now churn out more than 90% of its products, and wooed Chinese consumers, who in some years contributed up to a quarter of Apple’s revenue. Yet economic and geopolitical shifts are forcing the company to begin a hurried decoupling…

The two countries are the main beneficiaries of Apple’s strategic shift. In 2017 Apple listed 18 large suppliers in India and Vietnam; last year it had 37. In September…Apple started making its new iPhone 14 in India, where it had previously made only older models. The previous month it was reported that Apple would soon start making its MacBook laptops in Vietnam…Almost half its AirPod earphones are made in Vietnam and by 2025 two-thirds will be, forecasts JPMorgan Chase. The bank reckons that, whereas today less than 5% of Apple’s products are made outside China, by 2025 the figure will be 25%…

As Apple’s production system is shifting, its suppliers are diversifying away from China, too…

At its high point in 2015, China accounted for 25% of Apple’s annual revenues, more than all of Europe. Since then its share has steadily shrunk, to 19% so far.

I would also expect Indonesia, Bangladesh, the Philippines, Mexico, and Turkey to be in this bloc. There will also be some swing states like Malaysia that could go either way and might try to play both sides.

Between multinational shifts out of China and China’s indigenization of innovation and onshoring of supply chains, the economic relationship between China and developed democracies will stop being a symbiotic one and start to be a competitive one. Instead of being part of a value chain, Chinese and DD companies will go head to head in developing-country markets in Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa. Industrial policy in the DD countries will likely increase in order to maintain key technological edges that are relevant for military advantage.

Meanwhile, the geostrategic competition between the DD countries and the China/Russia axis is obviously going to rely on a lot of export controls. So I expect to see the return of the Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls (CoCom) or some equivalent, and its extension to various new technologies.

Finally, the disengagement from China is not going to be total or abrupt, no matter how much impetus there is in that direction. The DD countries are going to need to decide which products they can afford to keep sourcing from China and which they can’t. This is going to take quite a lot of planning, and it would be much better for the DD countries if they coordinated instead of trying to go it alone.

In fact, whether the non-China bloc coordinates on policy is really the big question regarding the new world-economic order. Together, the U.S., Europe, and the rich democracies of East Asia comprise a manufacturing bloc that can match China’s output and a technological bloc that can exceed China’s capabilities. With the vast populations of India and other friendly developing countries on their side, they can create a trading and production bloc that will be almost as efficient as the old Chimerica system. But this will take coordination and trust on economic policy that has been notably absent so far. The U.S. will have to put aside its worries about competition with Japan, Korea, Germany or Taiwan — and vice versa.

In any case, this vision — a largely but not completely bifurcated global system of production and trade, with two technologically advanced high-output blocs competing head to head — seems like the most likely replacement for the Chimerica system that dominated the global economy over the past two decades. But it’s only a loose guess. What’s not really in doubt here is that we’ve reached a watershed moment in the history of the global economy; the system we came to know and rely on over the past two decades is crumbling, and our leaders and thinkers need to be scrambling to plan what comes next.

I am writing from Hong Kong. A year ago I commented on one of Noah’s articles. The mood among the English literate Chinese middle class (my cohort) has turned to total despair. Noah was more right in 2021, our cohort got it wrong. X is worse than all of us thought. Those of us with the luxury to “run” are making back up plans to leave. Most cannot.

I was in China for 17 of the last 30 years and the times I was out of China,i was either doing graduate work, covering china from the USA or in HK. I worked in PE and VC and ran a start-up in the early days. One part that is glossed over is the disportionate treatment of the relationship treatment. In hindsight, while America looked to make money in China, China in some ways abused the relationship . This included forced technology transfer and the broad theft of corporate secrets. I had a long talk with a close friend who funded several deals and still lives in Shanghai. We both agree that this approach laid the groundwork for the current decoupling. Xi is also ushering in a different China that its citizens might not appreciate. Unlike the previous leaders, Xi is a pure politician and committed communist. China is now making it difficult to get or renew passports for its citizens. It has forced Zero Covid on its citizens because Xi cannot abide that China's domestic vaccines are weak and it would be embarrassing that a western/American vaccine would set the country back to work. China is running into somer serious economic headwinds that for years Chinese politicians have assumed that the country would never face- the middle income trap. This will cut down on economic growth. in addition, the CCP's plan to place communist party member into private company management will be a disaster. Part of the debt problem that the country faces is that politicians participated in loan decisions best left to the economics of banking. Now, imagine China's entire private sector now faced with the prospect that politics may enter into business decisions. Finally, China has an aging population which affects economic growth. This can be somewhat assuaged by immigration. However, China is making it very difficult for foreigners to live and work in China. According to a close Chinese friend, 5 years ago, Beijing had over 250,000 foreigners. Today, there are 25,000. It is an end of an era and I fear for my friends, both Chinese and foreigners, in China. 10 years ago, the Chinese I knew and met, students, investors, business people, laobaixin all looked forward to the array of opportunities in the future, better jobs, more money, travel. Increasingly, those rosy futures are dimming. China became a global power because of its economy. If it no longer has the same role in the world, what does it base its relevance on?