Developing countries: A follow-up

Checking in on some countries I wrote about a few years back.

Back in 2021-22, I wrote a series of posts about industrialization in developing countries:

I tried to evaluate each country’s growth model through the lens of industrial policy — specifically, the ideas in the book How Asia Works. The basic idea of that book is that developing countries should promote productivity growth through exports, using an approach called “export discipline”. That idea — summarized by Reda Cherif and Fuad Hasanov of the IMF in 2019 — is to use the financial system and other incentives to push companies to sell overseas, and to temporarily subsidize exporters in order to discover national champions.

Export discipline, according to its proponents, raises productivity by helping a developing country discover its comparative advantage, by forcing companies to compete in world markets, and by helping companies to import foreign technologies and adopt cutting-edge international business practices. Many industrial policy proponents cite South Korea as the best example of this type of strategy.

Several years have passed since I wrote those posts, and in those years there has been a lot of pessimism about economic development — and about industrialization in particular. The Covid recession generally hit poor countries harder than rich ones, and there are some signs that the trend of global income convergence that held before 2020 has now paused or even gone into reverse. Here’s Hartley (2024):

[The] great period of income convergence across countries since the 1990s through 2019 has been halted for several years in the early 2020s following the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, we find that rich countries are growing faster than poor countries from 2021 to 2023, potentially causing a pause in the so-called new era of unconditional convergence.

Hartley attributes the post-pandemic divergence to inflation, which hit poor countries harder, and suggests that poor countries will start catching up again as inflation subsides. But more pessimistic observers worry that the increasing global trend toward protectionism and economic nationalism will derail development, by closing off rich countries’ markets.

It does certainly seem that a global wave of protectionism, coupled with China’s attempt to become the world’s sole manufacturing powerhouse, reduces the scope for other poor countries to use the “export discipline” strategy. There’s also a worry that increasing automation in the manufacturing industry, now supercharged by AI, will destroy the traditional labor-cost advantage that has traditionally lured international manufacturing to poor countries.

So I thought I’d briefly revisit the developing countries I wrote about three or four years ago, and see how their growth has held up.1 Despite all the pessimism since the pandemic, I find that very few of the stories have changed.

(Growth charts here are from the World Bank; per capita GDP numbers are from the IMF via Wikipedia.)

The promising industrializers

In general, the optimistic development stories from my original series haven’t changed since the pandemic — we haven’t seen a growth acceleration among the industrializing countries, but with the exception of Bangladesh, we mostly haven’t seen a deceleration either. These countries should leave us hopeful that industrialization is still possible in this day and age, although it’s hard.

India

India is, of course, the most important developing country of all, simply because it’s the biggest. Whether India can get rich will determine much of the course of human flourishing over the next century.

Before the pandemic, India’s growth was looking a bit anemic, having lost steam since the 2000s due to a banking crisis and other factors. In the years since Covid, growth at first rebounded strongly, to 7% or 8%, but then slumped a bit in 2024:

This is a steady but unspectacular rate of growth — 5% will double a country’s living standards in about a decade and a half. But that isn’t fast enough to let India get rich before it gets old, so India really needs to speed things up to 8% or better.

There has been some optimism around Indian industrialization since the pandemic. A lot of companies see India as a way to “de-risk” from China, as war risks mount and China squeezes multinationals out of its markets. Apple, in particular, has been moving manufacturing to India at a rapid clip. And India’s Prime Minister Modi has been building lots of infrastructure, addressing the country’s most notorious weakness. Modi also unleashed an industrial policy program called “Make in India”.

However, there are also some big headwinds. India’s education system still isn’t performing very well, and women — traditionally the backbone of early labor-intensive industrialization — still aren’t moving from small towns to big cities en masse. The urbanization rate is still low. China is trying very hard to prevent India’s rise as a manufacturing rival, withholding key technology and forcing its engineers to leave India in order to avoid transferring their skills. And Trump’s tariffs are going to make life harder for the Indian export machine.

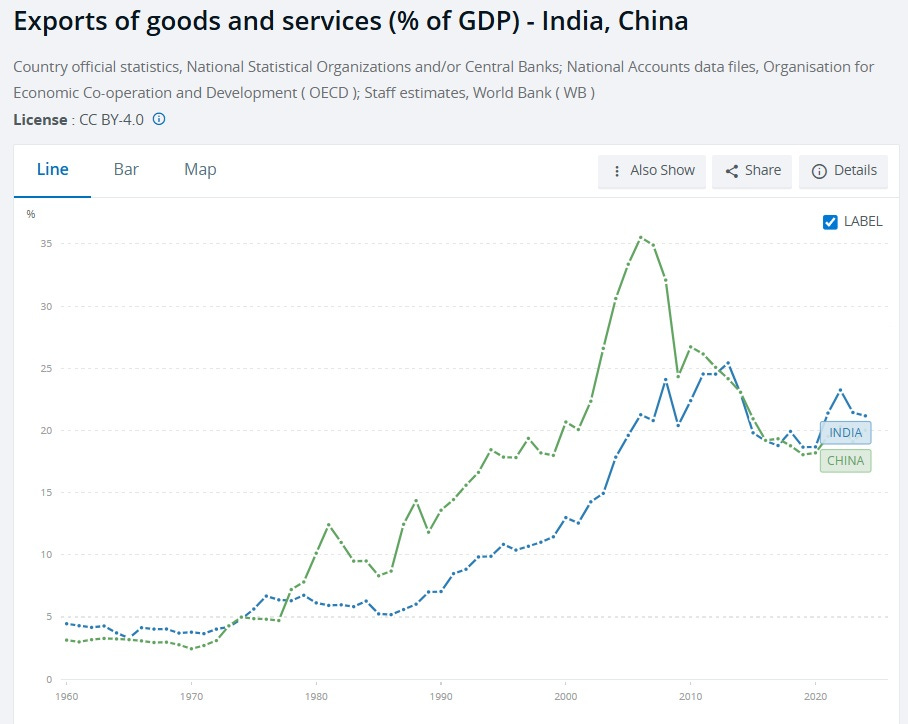

As a result, Indian manufacturing has actually fallen as a percent of GDP (though some Indian statisticians argue that the sector is mismeasured and is actually much larger). India is a stronger exporter than China in the 1990s, but not nearly as strong as China in the 2000s:

I’ll write more about Indian industrialization soon. Given its size and its government’s determination to accelerate growth, I think it’s the world’s most promising industrialization story, despite its struggles.

Bangladesh

Bangladesh was a standout performer in the 2010s, catching up and surpassing Pakistan’s living standards. The government heavily promoted the garment industry, until Bangladesh became a major world player and even outcompeted China to some extent. Investment levels were high, and growth was running at a healthy 6%.

But in 2023 and 2024, Bangladesh’s growth plunged:

What happened? Basically, Bangladesh ran into the great killer of development: political unrest. Political violence began rising around an election in 2023, and in 2024 a protest movement deposed the country’s long-standing ruler, Sheikh Hasina. This naturally disrupted the country’s economy, hitting the all-important garment industry hard and leaving industrial policy up in the air.

But even before the revolution of 2024, Bangladesh was in a bit of trouble — the country hadn’t managed to diversify its manufacturing industries to electronics or other higher-value products, and exports were still low as a percent of GDP despite the success in garment manufacturing. Even in garments, wages weren’t rising much, suggesting stagnant productivity. Basically, Bangladesh took full advantage of its labor cost advantage in a single industry, but failed to do much more than that. And with its politics having been heavily disrupted, it’s not clear that it will have the leadership to build on the success in the garment industry.

So that’s fairly disappointing.

Vietnam

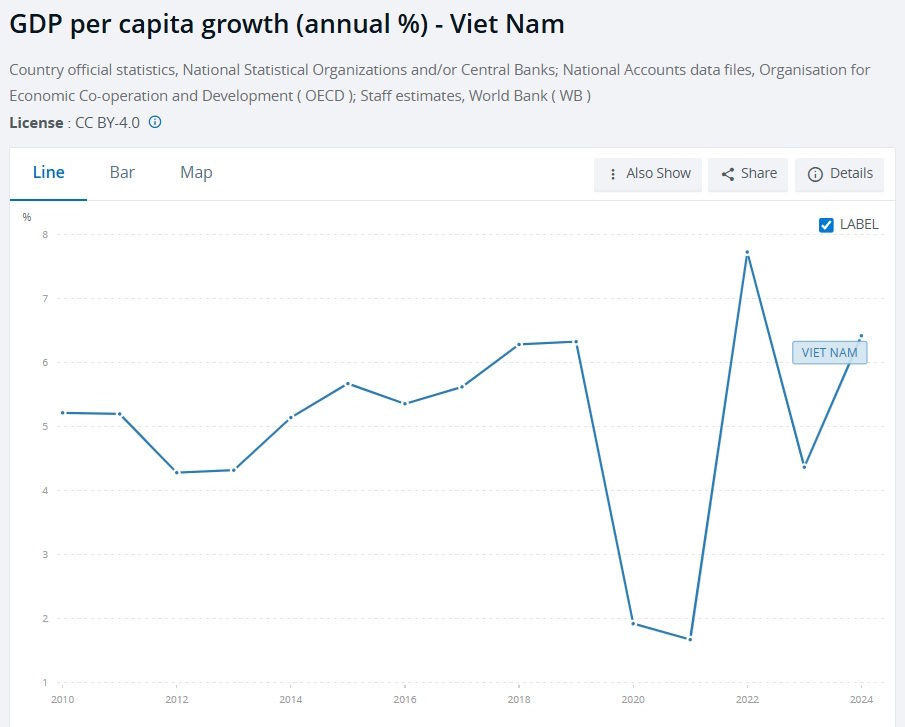

Vietnam has been another solid developer, with growth running at 6% before the pandemic. That growth has held up since the pandemic:

Vietnam has now reached over $17,000 in per capita GDP (PPP), so it’s no longer a poor country. But it faces some major headwinds that it’ll have to overcome if it wants to advance to the next level. The Economist recently had a good article about the limitations of Vietnam’s low-cost export model:

Vietnamese workers are simply assembling parts made, by and large, in China or South Korea. Even as export volumes have ballooned, the average unit value has stagnated…Vietnam adds less value to its exports than do nearby Malaysia and Thailand. Because final assembly is labour-intensive, productivity is low…Local firms struggle to meet the standards necessary to take part in global supply chains…Despite Samsung Electronics’ huge presence in Vietnam, none of its core suppliers is a homegrown Vietnamese firm…

Meanwhile, Vietnam has reached the “Lewis turning point”, at which developing economies exhaust their rural labour surpluses and wages begin to rise swiftly…Vietnam could soon end up too expensive for labour-intensive manufacturing yet too technologically unsophisticated to do much else—a classic middle-income trap.

Vietnam has lots of exports, but few domestic supply chains, keeping it trapped at the bottom of the “smile curve”, doing the low-value assembly work but not making high-value components.

This suggests an important modification to the standard “export discipline” approach. If countries want to be great manufacturers, they can’t just find a few industries they’re good at; they need to work on developing whole domestic ecosystems of interrelated industries. That’s in addition, of course, to more traditional policies like improving higher education, which Vietnam also needs to do.

Indonesia

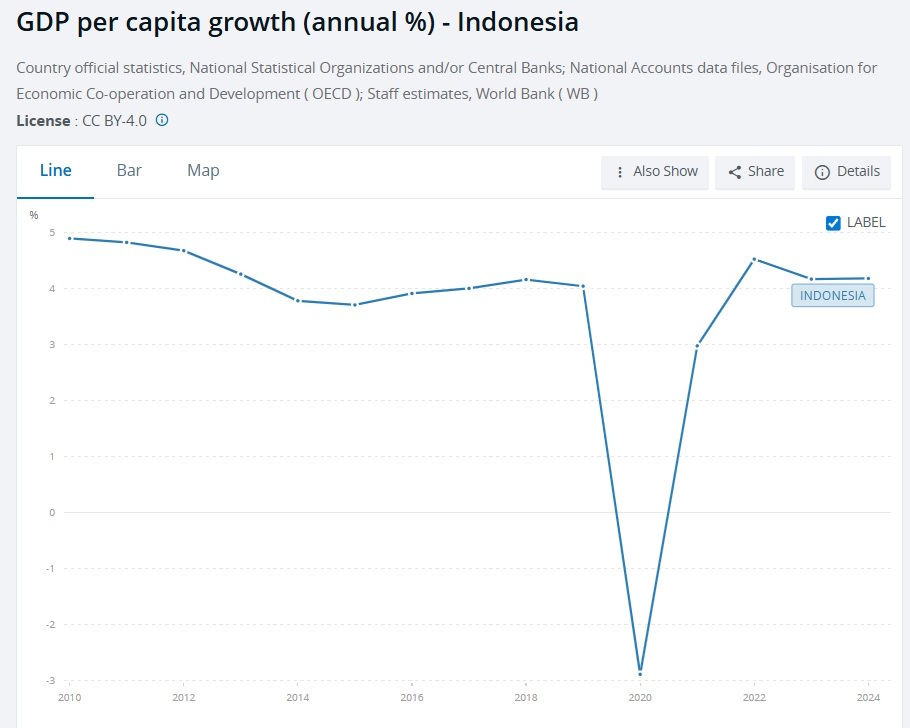

In my post in 2022, I praised Indonesia for being able to maintain a solid rate of growth even while switching from export manufacturing to natural resource exporting (and perhaps switching back again). That story has continued since the pandemic.

But this success has to be put in perspective; Indonesia’s growth is only around 4%, which is faster than the developed world, but only by a little bit.

This slowish rate of growth will allow Indonesia to double its living standards every 17 years or so, but won’t be enough to let Indonesia get rich before it gets old. Indonesia is already at over $17,000 in per capita GDP (PPP) — about as rich as Vietnam — but is growing more slowly.

Being a natural resource exporter has saved Indonesia from poverty, but it won’t be enough to get rich. Indonesia should probably do a lot more to promote reindustrialization.

Philippines

The Philippines has been an unexpected bright spot, growing at a solid 5% before and after the pandemic:

The country has managed to avoid political instability, despite electing the son of a controversial and corrupt former leader. Exports are unspectacular but solid, and based mostly around manufacturing and business services. And with a fertility rate that’s still above replacement and falling only slowly, the Philippines has a little breathing room; it can afford to grow a little more slowly than its neighbors in per capita terms, because it’s not in danger of growing old soon.

I’ll have more to write about the Philippines soon, but right now I’m cautiously optimistic.

The slow growers

Overall, the development disappointments that I highlighted in my original series are mostly still disappointments, mired in slow or zero growth. Ghana is the one partial exception. The main lesson from these countries is that political and social instability destroys development, and tends to be very hard to kick.

Pakistan

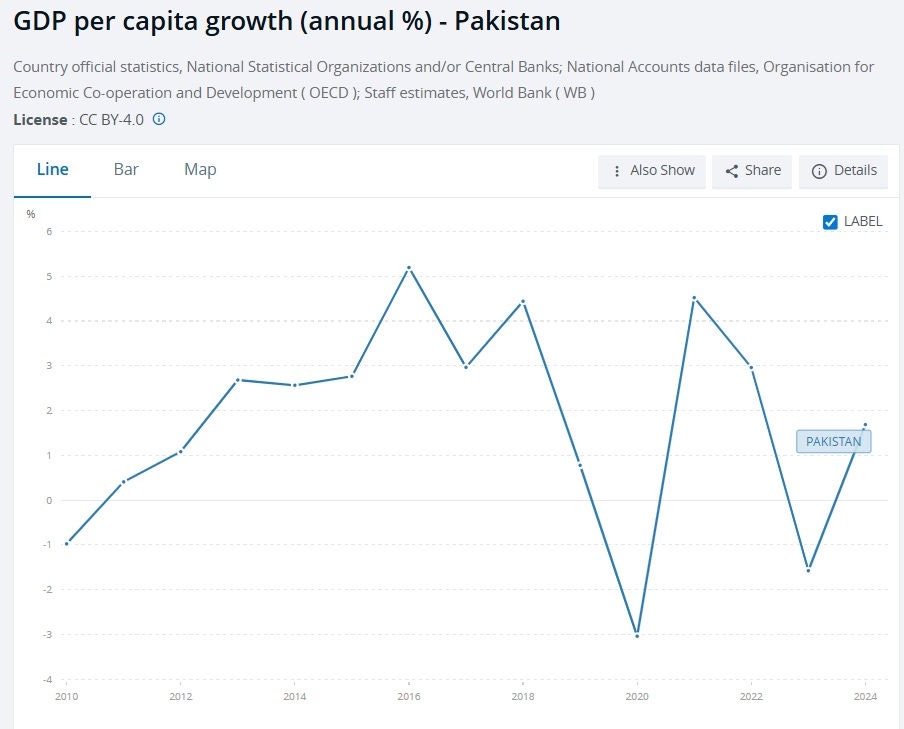

Pakistan is one of the world’s great economic basket cases. It invests very little of its GDP, it’s mired in desperate poverty, and it subsists on a steady stream of unrepayable loans from the IMF and China. Things looked a little brighter for a couple of years before the pandemic, but since then, the country has returned to essentially zero growth:

Pakistan’s biggest problem is its perpetual political instability, with power switching back and forth between the military and civilian leaders. That instability continued in 2022, with the ousting of Prime Minister Imran Khan. Because no one really knows who will be in charge of Pakistan in the near future, it’s very difficult to plan or invest for the future.

And the country’s leaders — whoever they are this week — know that their possession of nuclear weapons, their strategic location, and their influential position in the Islamic world will always allow them to muddle along, subsisting on cheap loans and free cash from abroad, never starving but never getting any richer, appeasing their population with waves of nationalism from the occasional inconclusive skirmish with India. Meanwhile the country’s fertility is still pretty high at 3.6, and declining only slowly, making it harder and harder to sustain per capita incomes without industrialization.

It seems to me that this dysfunctional economic model can’t continue forever without something breaking.

Mexico

Mexico’s economy is stuck. Growth was barely above zero before the pandemic, and it’s barely above zero now:

Fortunately, Mexico is stuck at a decent level of income — over $25,000 per person at PPP. That’s not rich, but it’s far from poor. So unlike Pakistan, Mexico’s lack of growth is not a disaster — it’s just a bit disappointing.

Mexico continues to have every advantage going for it, and just can’t seem to capitalize fully. It’s right next to the U.S.’ huge market, and it does tons of export manufacturing. It has a large domestic market too. It should be able to grow more than it has, and it’s a bit of a mystery as to what exactly is holding it back. I’ll write more about this soon, but Mexico’s seemingly never-ending drug war is probably a big factor.

Jamaica

Jamaica is another middle-income country that doesn’t grow at all. Its economy was flat before the pandemic, and has been flat since then:

Jamaica has tried to boost its manufacturing sector, but to no avail; the country continues to subsist mostly on tourism. That’s enough to keep Jamaica at a middle income level of about $12,000 per capita (PPP) — so, not a tragedy like Pakistan, but very far from an economic success.

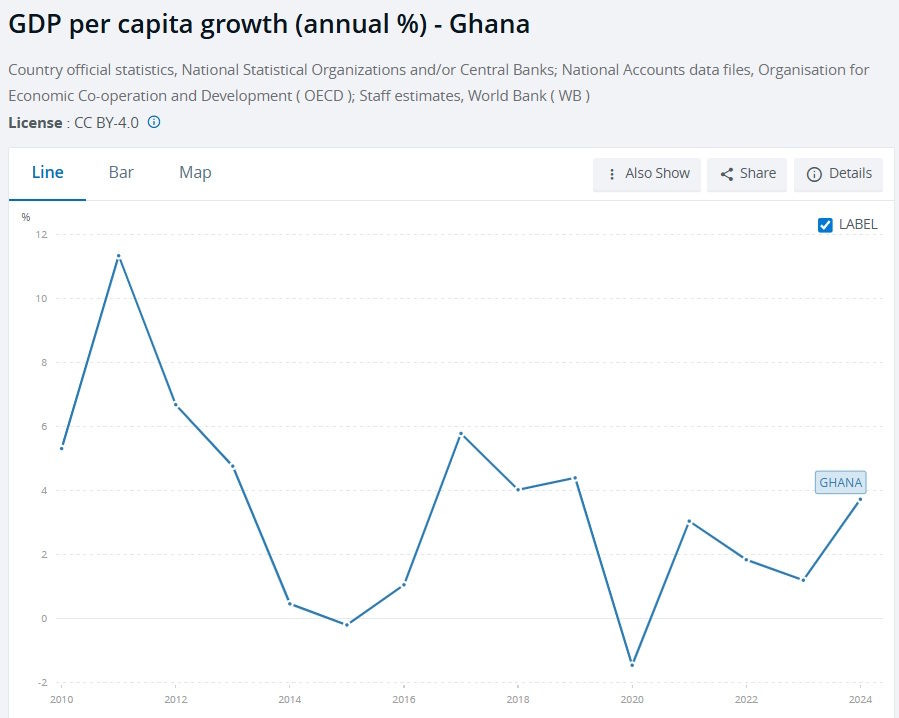

Ghana

Ghana is a poor country without much manufacturing to speak of. But as poor countries without manufacturing go, it’s doing OK. The country rarely sees a recession, and didn’t suffer much from Covid. Its growth is pretty variable, but in some years it’s pretty solid:

Ghana has political stability, and it provides much better education and health care than neighboring countries do. It doesn’t just export natural resources — it also exports a lot of business services, serving as a sort of business hub for West Africa. A recent currency crisis came and went, and didn’t seem to faze it that much. Ghana won’t stop being a poor country soon, but it’s doing a lot better than its peers, and nothing ever seems to derail it.

The newly rich countries

Several countries have joined — or almost joined — the ranks of developed nations over the past couple of decades. All four of the ones I noted in my initial series are still going strong, with most of them continuing to catch up to even richer nations. This is extremely encouraging, as it shows that countries can still catch up all the way to developed status even without world-beating national champion manufacturers like Samsung and Hyundai.

Poland

Poland ranks only behind South Korea as the great economic miracle of modern times. In 1990 it was a dysfunctional post-communist economy that was significantly poorer than Russia; now, the IMF expects it to soon overtake Japan, Spain, and Israel in per capita GDP. Poland is now a developed country.

And it’s still going strong. The pandemic barely fazed Poland, and its economy continues to grow faster than that of most rich countries:

The country’s economic model deserves to be studied and replicated. It’s really just good institutions, good education, and promotion of foreign direct investment. The latter counts as industrial policy, of course, but it’s much less complicated and ambitious than what Korea did.

Malaysia

Malaysia is now almost as rich as Greece, and still growing faster than most rich countries:

The country’s economic model has relied heavily on the electronics industry, and on foreign direct investment, though it still exports some natural resources too. It should be another case study for other developing countries to imitate — especially in Southeast Asia.

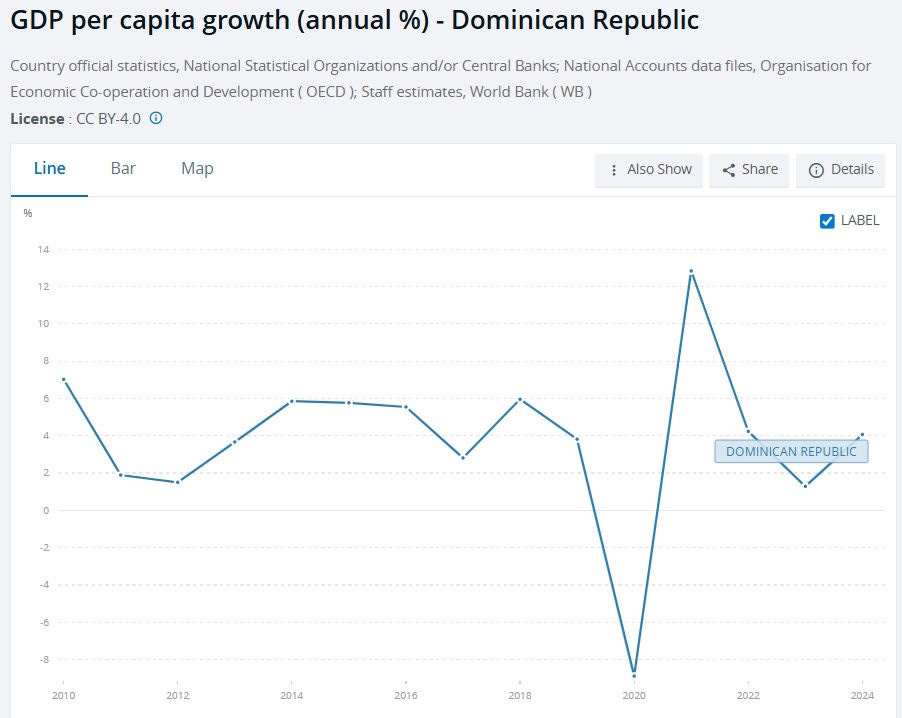

Dominican Republic

Few Americans seem to know how successful the Dominican Republic has been; the “Caribbean shark” is a well-kept secret. Its per capita GDP (PPP) is now over $30,000 — about the same as Argentina, and slightly richer than China. And at 4%, its growth is almost as fast as China’s, having slowed only a little bit since the pandemic:

The D.R. gets a lot of tourism dollars, but it also does a fair amount of export manufacturing — mostly for the U.S. It’s a model of balanced development and good government, and it deserves more attention.

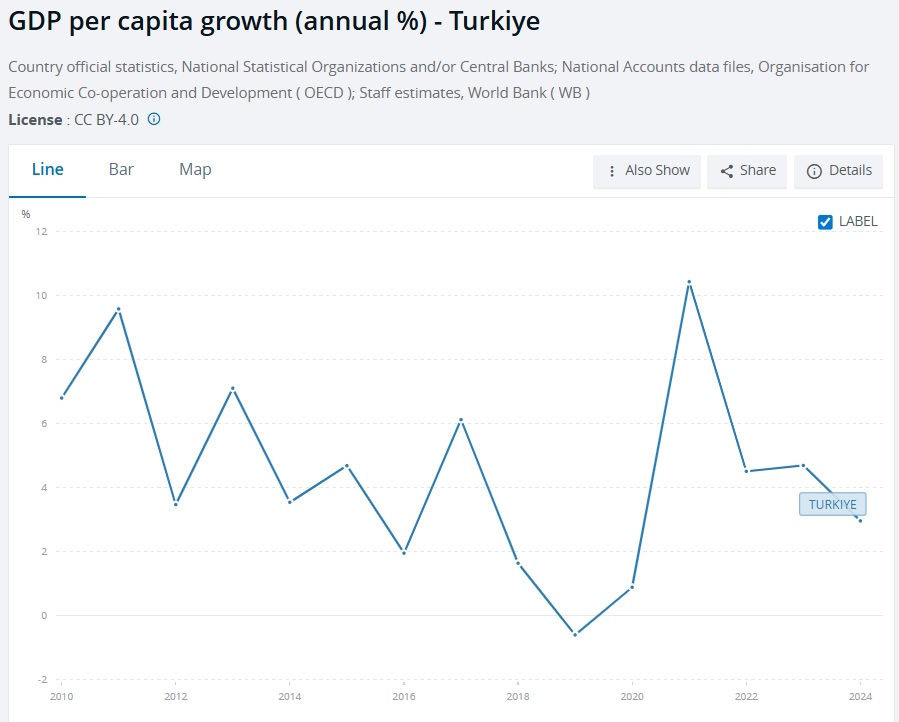

Turkey

Turkey is essentially a developed country now, with per capita GDP of over $42,000 at PPP — about the same as Malaysia. The country sailed through the pandemic without a recession. But unlike Malaysia or Poland, Turkey’s growth has slowed to typical developed-country levels:

Fortunately, the country’s dysfunctional macroeconomic policy (based on the idea that low interest rates reduce inflation) has been set aside. But this means interest rate hikes to control inflation, which have slowed the economy. At this point, Turkey should be regarded as a slightly-poorer-than-normal developed country, much like Greece, whose economic challenges are more macroeconomic and institutional than industrial.

I omitted Ukraine, which is in the middle of a major war, and Haiti, which I only wrote about as a comparison with the more successful Dominican Republic.

Love the series! It looks like southeast asia, India, and Bangladesh (conditioned it can be stable again) is the next round of fast growth. That's still over 1B people to leave poverty so that's great.

I'm Ghanaian and love your summary. But just to add, Ghana, and most of Africa basically had fast growth from 2000-2014 because of high commodity prices due to China. Since then it's been stagnate growth for most African countries save Cape Verde, Ivory Coast, and a few others.

I've made a couple series on the history of some African countries (from pre-colonial, colonial, and modern day economics & geopol) for reading/audio. Here's 3 I recently did:

Here's Rwanda:

https://yawboadu.substack.com/p/the-economic-and-geopolitical-history-174?r=garki

Uganda:

https://open.substack.com/pub/yawboadu/p/ugandas-economic-and-geopolitical?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=garki

Tunisia:

https://yawboadu.substack.com/p/the-economic-and-geopolitical-history-88d?r=garki

For Mexico it is also corruption, from the ground up. And the lack of a strong, fair judicial system. It is not a country where, if something wrong were to happen to you, you feel safe and confident that the judicial system will take care of you. It is highly corrupt as well. Such a great country, great people, but so much working against it.