Biden is right that we need to raise taxes

But his plan needs a lot of work.

Biden’s Treasury Department just released a tax plan for 2025. Unless Democrats sweep to power in a wave election (which doesn’t look likely), most of these proposals aren’t going to make it into law. But it’s worth examining the proposal anyway, because…well, because this is an economics blog, and that’s what we do!

My take on this plan is basically that yes, we need to raise taxes in the U.S., because of big deficits and higher interest rates. And most — though not all — of Biden’s suggestions about how to do that are actually pretty good ideas. Capital gains taxes and estate taxes, which are the mainstay of the proposal, could both stand to go up in this country.

But there are a number of big problems with the plan as well. First of all, the idea of taxing unrealized capital gains — which is now unfortunately a fixture among progressive intellectual circles — is a bad one, since it defeats much of the purpose of taxing capital gains in the first place. Second, Biden is proposing to use much of the tax increases to fund health care subsidies, which will increase the price of health care, at a time when people are mad about rising service prices. And third, the rhetoric in the plan is all about reducing racial wealth gaps, which seems likely to alienate a lot more voters than if it were couched in terms of deficit reduction (though this is a political concern rather than an economic one).

So I think the plan has some very good pieces, but needs a lot of work. I’ll try to keep these points fairly succinct, so as not to bore you, but here goes.

Why we need to raise taxes (and cut spending)

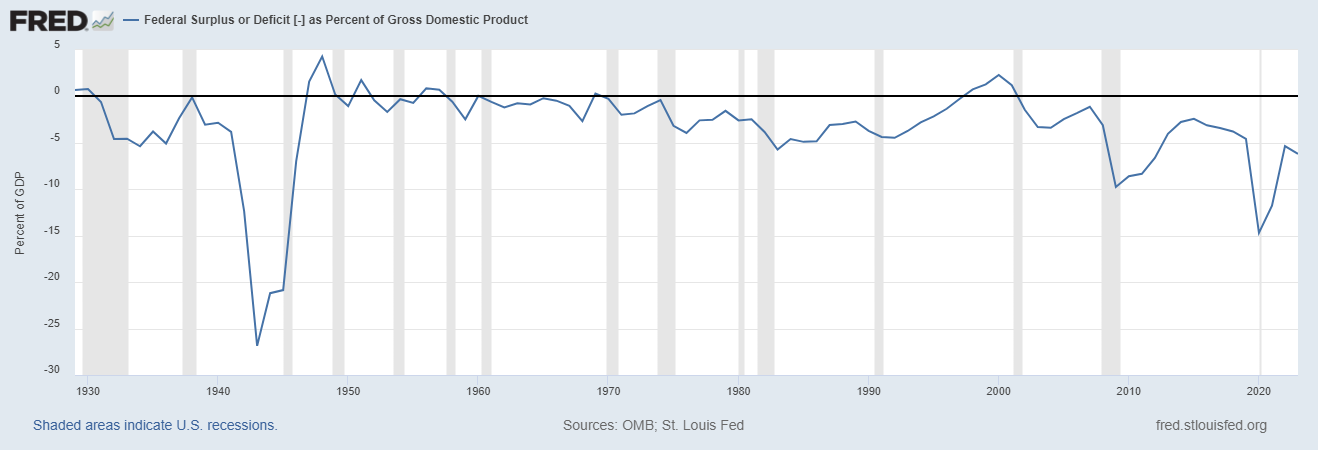

The U.S. government is running a big deficit:

This doesn’t look good. The pandemic is over, and the economy is doing great. According to the principles of standard Keynesian macroeconomic management, this should be the perfect time to get deficits under control. For one thing, inflation is still above target, and fiscal deficits may be contributing to inflation. Also, interest rates are fairly high, so borrowing right now increases interest costs by a lot. That’s a problem the U.S. hasn’t faced since the 1990s:

Perhaps the MMT people would advise us to just keep borrowing more and more to cover these interest costs, and then borrow even more to cover that interest, etc. That is a bad idea; eventually something in the economy will break. We’ll eventually get a default premium on government bonds, or hyperinflation, etc. In order to avoid the possibility of that, and to avoid having the rest of the budget crowded out by interest costs, the U.S. government will have to get deficit spending under control.

There are two ways we can get deficits under control: 1) cut government spending, and 2) raise taxes. That’s it — those are the only options. So which should we do in this case? Breaking down the deficit into taxes and spending (both as a percent of GDP, of course), we can see that spending is historically high right now, while taxes are historically low:

I drew the purple lines to mark where we are right now. As you can see, spending is higher than it’s been in recent history, except for during the Great Recession. And taxes are lower than they were under Reagan, Clinton, and (mostly) Bush. If we think that the 80s, 90s, and early 00s are a good guide to what our taxes and spending should be, it means we should cut spending and raise taxes right now.

Now you could make a libertarian argument that we should do deficit reduction entirely with spending cuts, because taxation is theft, because government spending is wasteful, and so on. And you could make a progressive argument that we should do deficit reduction entirely with tax increases, because reducing inequality is good, and because pretty much everything the government is spending money on now is good and important. I could argue with both of these cases, but I’m not going to, because A) a political compromise on deficit reduction will inevitably end up with some mixture of spending cuts and tax increases, B) this is what we did in the 90s and it worked, and C) this is what other countries do when they successfully reduce deficits.

So taxes should go up. And two of the best kinds of taxes we could raise right now are capital gains taxes and estate taxes.

Capital gains taxes, estate taxes, and accrual taxes

Biden’s plan has three ideas for tax hikes:

Raise capital gains tax rates to the same rate as the tax rate on other kinds of income,

Eliminate the “step-up basis” that allows people to dodge capital gains taxes if they inherit assets, and

Create a 25% minimum income tax for the wealthy that includes unrealized capital gains as income.

Basically, I think the first two of these are good ideas, and the third should be dropped.

When deciding what kinds of taxes to raise, we have to take a few considerations into account. First, there’s the question of fairness — who we think should be paying taxes. Second, there’s the question of what kind of behavior taxes encourage and discourage; if you want people to save more money, you probably shouldn’t tax their savings. Changing economic behavior can also distort the economy and make the whole country poorer. Finally, there’s the question of how much revenue you can feasibly raise from a particular tax.

In general, capital gains taxes are a decently good way to tax an economy. On the fairness side, they affect rich people a lot more. Rich people own a disproportionate share of assets in the first place, even relative to their income; this is why wealth inequality is much higher than income inequality. This means capital gains taxes will hit rich people a lot harder than everyone else.

Also, capital gains taxes don’t seem to distort economic behavior very much. Theoretically, taxing capital gains more gives people an incentive to invest less in the stock and housing markets, because the rate of return they can make is less. This could cause markets to fall in the short term, and make it harder for businesses to find financing in the long term. If so, it would also increase consumption, because the only thing you can really do with your money other than save it is to spend it today. But higher capital gains taxes may also keep money in the market, via a “lock-in” effect — if you wait longer to sell your stocks or houses, your gains can compound more, reducing your overall tax bill. Economists argue about how big these effects are.

Historically, though, changes in capital gains tax rates don’t seem to do much to the stock market. For example, when Biden started talking about raising capital gains taxes in 2021, some Goldman Sachs people noted that we’ve actually changed the tax rate a bunch of times, and didn’t see much action in the market:

There is plenty of evidence that higher capital-gains taxes make people sell stocks less often, but this could just be because they’re waiting for the tax rate to go down again in the future. In general, people just don’t change their behavior much in order to try to avoid capital gains taxes.

Meanwhile, dividend tax cuts, which are somewhat similar to capital gains tax cuts, don’t seem to induce businesses to increase capital spending. So the economic distortion of higher capital gains taxes is probably not huge. And on the revenue question, Sarin et al. (2022) argue that capital gains taxes would be a big revenue raiser, because people aren’t likely to take their money out of the market in the long term — especially now that most stock investment is through index funds and ETFs.

So capital gains taxes are probably not a bad way to fund the government. Biden’s plan, which would raise the long-term tax rate on capital gains to be the same as the tax rate on ordinary income, would likely raise a lot of money from wealthy people, without hurting the overall economy that much. There are a number of small problems with it, but that’s generally true of any other tax as well, and there are small fixes that could be applied. This is why Bill Gates has been calling for a higher capital gains tax for years.

Currently, a big way that people dodge capital gains taxes completely is to inherit the money. The “step-up basis” policy says that if you inherit stocks or a house, you never have to pay taxes on the amount those assets appreciated from the time they were purchased. In fact, that tax never gets paid by anyone. Inheritance just washes the tax liability away forever.

This is pretty obviously a huge loophole in the U.S. tax code. Even tax planners who advise you to use this strategy call it a “loophole”. There’s zero economic rationalization for why inheritance should be taxed less than other income; in fact, most people probably believe that rich heirs are especially undeserving of their windfalls of dynastic wealth. Over time, the step-up basis loophole contributes to a society of dynastic, entrenched inequality. Also, there’s evidence that estate taxes don’t change savings behavior, so eliminating the step-up basis loophole probably wouldn’t cause Americans to save less.

Biden’s tax plan would eliminate the step-up basis loophole entirely, taxing the capital gain income at the time it’s inherited. This seems like an obviously good idea. (There’s also another well-known estate tax loophole that Biden’s plan would close; this is also good, though I won’t go into it here.)

But Biden’s third proposal — taxing unrealized capital gains as income — is just more trouble than it’s worth. Capital gains taxes are collected only when you sell an asset. This has long irked progressives, who grumble at the idea that rich people are seeing their wealth increase by leaps and bounds every year without being taxed a penny.

Biden’s plan would “fix” this problem by taxing asset appreciation before the assets are sold — an idea that’s sometimes called an accrual tax. But as I wrote in Bloomberg back in 2019, this could seriously hurt startup formation:

[T]axing unrealized gains would force asset owners to sell some of their holdings [each year] in order to pay their taxes. For some assets, like publicly traded stocks, that’s no big deal, because their markets are big and liquid, with many buyers and sellers. But imagine the stock of a startup…When the startup’s stock appreciates in value because it accepts funding at a higher valuation, the founders, early employees, and early investors would probably have to sell some of their stake in order to make the tax payments. Finding a buyer would be difficult and time-consuming, and they might have to sell at a big loss, hurting the company’s development.

A much less chaotic and disruptive way to address the issue of unrealized gains, suggested by Alan Auerbach, would be to simply charge people interest on their past gains when they eventually sell their assets. If the step-up basis loophole is fixed, retroactive capital gains taxation does the same thing as accrual taxation, but without the liquidity problem.

So Biden should switch from suggesting accrual taxes to proposing charging interest on past capital gains. If he doesn’t make that switch, the accrual tax proposal is probably dead on arrival, since it would be too disruptive to the startup economy — which is a key engine of American economic growth.

With that one important exception, the tax proposals here are pretty good. But when it comes to spending proposals, the plan has major problems.

We don’t need to throw more money at overpriced services

The money from higher taxes should be used either for deficit reduction, or for high-priority spending items. Biden’s plan doesn’t talk about deficits at all; instead, it proposes using the revenue from higher taxes to expand the welfare state in two ways:

Restoring the expanded Child Tax Credit from the American Rescue Plan, and

Making permanent the Inflation Reduction Act’s tax credit for health insurance premiums.

The first of these is a good idea. It’s the closest thing America is going to get to a universal basic income anytime soon. Unconditional cash transfers are probably the most efficient form of welfare state possible, and focusing the transfers on families with kids is a pro-natalist policy as well. Mitt Romney proposed something a bit like this.

But it’s questionable whether we can afford a UBI-type spending proposal right now, given higher interest rates, high deficits, and the demands of other major spending items like industrial policy and national security. It might be a good idea to shelve the expanded CTC for right now, especially because it didn’t turn out to be very politically popular the first time around.

Biden’s health care spending proposal, meanwhile, is just plain misguided. Health care is one of our most overpriced industries; the growth in medical care prices has outstripped median income by leaps and bounds over the last four decades.

These high prices are the reason why the U.S. health care system costs more than twice as much as other rich countries’ systems, despite not being better in quality. Bringing these prices down should be our number one priority.

Health care subsidies move us in the exact opposite direction. When you subsidize the demand for something, its price goes up. This generates calls for more subsidies, perpetuating the cycle — what the Niskanen Center calls “cost disease socialism”. Ultimately, we end up with a health system that’s both dreadfully inefficient and ruinously expensive. Arguably, we’re there already.

The urge to shovel money at already-overpriced service industries was always the weakest part of Bidenomics. Not only can the money be better spent elsewhere, but there’s reason to believe increased health insurance subsidies are just exacerbating America’s cost disease.

Racial justice rhetoric is probably not the best justification here

I should probably mention one more big problem with Biden’s plan, which is the rhetorical justification it gives for all of these proposals. The title of the Treasury Department’s plan is “Advancing Equity through Tax Reform: Effects of the Administration’s Fiscal Year 2025 Revenue Proposals on Racial Wealth Inequality”. The entire document basically just talks about how the various tax and spending proposals will shrink racial wealth gaps.

Now, racial wealth gaps are big, and I don’t like them at all. Racial wealth gaps are bad. But if that’s the only justification the Biden people have to offer for raising taxes on the American people, I doubt this plan will pass in any form. The idea of racially redistributionary policies is not popular with the American people. For example, reparations for slavery are highly unpopular, including among the growing Hispanic and Asian swing constituencies:

The thing is, we have plenty of reasons to raise taxes — and to spend money on the welfare state — that have nothing to do with racial wealth gaps at all. The deficit needs to be reduced. Child poverty needs to be reduced even among White people. The revitalization of American manufacturing needs to be funded.

Instead of making racial wealth gaps the single overriding reason for this tax plan, the Biden people should cite all these other reasons as well. I don’t think the rhetoric about racial wealth gaps should be dropped, but I don’t think it should take center stage as well. A proposal like this will have enough trouble passing without making it seem like a zero-sum racially targeted thing.

Anyway, to sum up, I think this Biden tax plan has some extremely promising elements, but it needs a lot of work. Changing the accrual tax proposal to a retroactive capital gains tax, eliminating the health insurance subsidies in favor of deficit reduction and industrial policy, and adding a bunch more reasons for the plan other than closing racial wealth gaps would all go a long way toward increasing both the plan’s effectiveness and it’s chances of passing.

While I agree with the post, what is missing from the discussion is the absolute need for tax simplification. Raising taxes on an over complex tax code is always a fool's errand. I continue to reference TR Reid's fine book, "A Fine Mess: A Global Quest for a Simpler, Fairer, and More Efficient Tax System." there is an absolute need to eliminate all tax preferences and increase the personal deduction in return. We need a Value Added Tax in return for lower corporate income taxes (which are always gamed and can never keep up with clever accountants and tax lawyers). This would lead to an elimination of off shore tax havens.

In my case, the government knows all of my income through various income reporting forms and under any reasonable tax system, I should simply be able to signoff on my tax return in five minutes without having to us Turbo Tax every filing season.

Tax simplification can relieve taxpayer headaches and raise more revenue at the same time. Occam's Razor at work!!!!

A few comments: 1) estate taxes play havoc on small and mid-sized businesses as one generation builds on the equity from the other; 2) the Biden "equity" is a bad idea. It would foster more distrust of the tax collection system than currently. Being treated equally and fairly is the only reasonable basis; and 3) I get concerned when the talk is about raising taxes and cutting spending. While, in principle, I support it, politicians will always find ways out of raising taxes and compromising out of the spend side. Among the vehicles they use are accounting gimmicks, double counting and time-bound cuts. Remember, one Congress can bind another.