At least five interesting things: Requiem for capitalism edition (#63)

Buffett's secret sauce; Trump's price controls; More bad Abundance critiques; The software employment bust; British productivity

The theme of this week’s roundup is the fall of capitalism. With Trump going for price controls and tariffs, and anticorporate progressives savagely attacking Ezra Klein for wanting to build more houses, the political constituency for capitalism seems moribund for now. Meanwhile, Warren Buffett is retiring, hiring in the tech sector also seems dead, and the UK seems to have embraced degrowth. What’s a capitalist to do in times like these?

But first, an episode of Econ 102, about (what else?) tariffs:

Anyway, on to the list:

1. How did Warren Buffett invest so well?

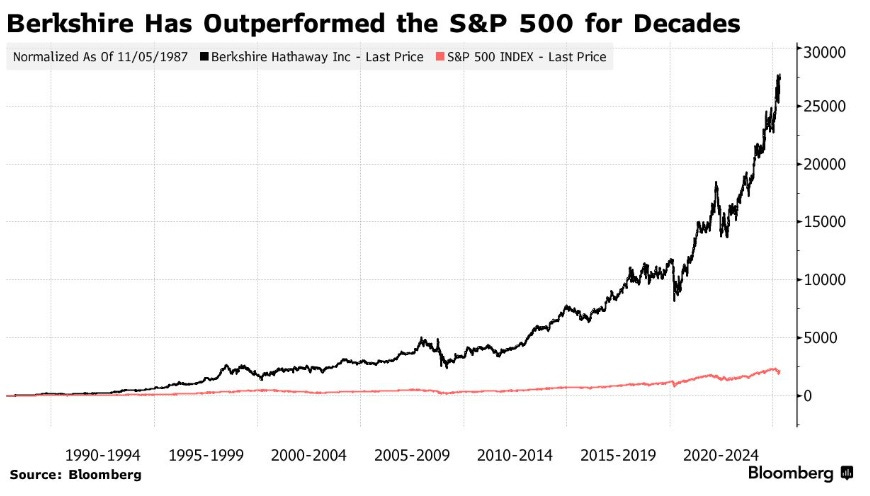

An investing legend has passed into history. Warren Buffett, the chairman and CEO of Berkshire Hathaway, announced that he will step down at the end of this year — at the age of 95. Over the decades, Berkshire — the vehicle through which Buffett made his investments — has beaten the stock market spectacularly:

If you invested a thousand dollars in the S&P 500 back in 1964, you’d now have several million dollars. If you invested it in Buffett’s company instead, you’d now have over a billion dollars.

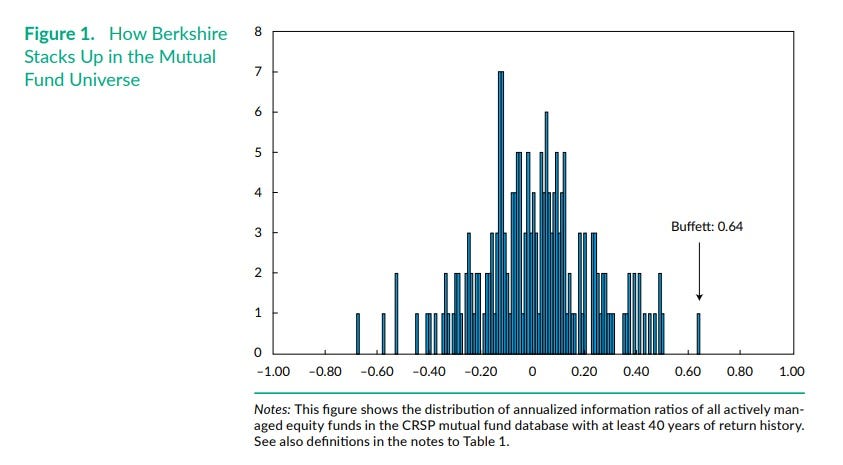

And in terms of his Sharpe ratio — the measure of his excess returns relative to the amount of risk he took — Buffett stands alone above all other mutual funds:

Buffett thus did something that finance theory says no investor should be able to do: He beat the market, consistently, by huge amounts. What’s more, his market-beating returns compounded — unlike most top investment funds, which will make you withdraw some of your money every year instead of reinvesting it into the fund, Buffett simply kept turning all of Berkshire stockholders’ money into more money at stupendous rates.

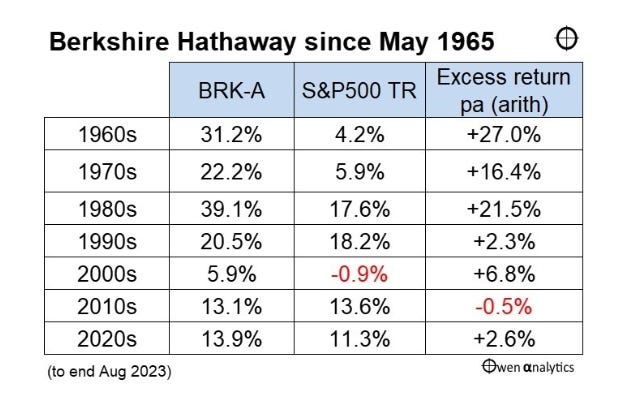

Well…almost. Buffett beat the market by a lot more in his early decades:

The simple explanation is that when Berkshire got big enough, it became harder and harder to keep finding as many mouth-watering overlooked investment opportunities for that growing pile of cash. Buffett’s returns took a heck of a long time to attenuate, but attenuate they did.

Another big question is how much of Buffett’s performance could be attributed to systematic approaches that any investor can copy, and how much was due to some ineffable individual talent. Books have been written about the “Warren Buffett Way”, but can regular people really be their own Buffett?

Frazzini et al. (2018) say yes, they can. They find that Buffett’s entire outperformance against the broader market can be explain by two systematic factors that they call “betting against beta” (BMJ) and “quality minus junk” (QMJ):

A loading on the BAB factor reflects a tendency to buy safe (i.e., low-beta) stocks while shying away from risky (i.e., high-beta) stocks. Similarly, a loading on the QMJ factor reflects a tendency to buy high-quality companies—that is, companies that are profitable, growing, and safe and have high payout…

Buffett likes to buy safe, high-quality stocks. Controlling for these factors drives the alpha of Berkshire’s public stock portfolio down to a statistically insignificant annualized 0.3%. That is, these factors almost completely explain the performance of Buffett’s public portfolio. Hence, a significant part of the secret behind Buffett’s success is the strategy of buying safe, high-quality, value stocks…Our statistical finding is consistent with Buffett’s own words from the Berkshire Hathaway 2008 Annual Report: “Whether we’re talking about socks or stocks, I like buying quality merchandise when it is marked down.”

But I’m not so sure the story ends there. In finance theory, factors that explain returns are supposed to be risk factors — in an efficient market, the excess expected returns in the long run are supposed to compensate you for the risk you take in the short run. “Betting against beta” doesn’t sound like a risk factor, because beta (correlation with the overall market) is itself a risk factor — instead, it sounds like a market inefficiency, where investors take on too much beta for too little gain. Similarly, it’s hard to imagine why “quality” stocks — companies that are profitable and growing — would be systematically riskier than other stocks.

A likelier explanation is that in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, the U.S. stock market was just somewhat inefficient — investors were just making a bunch of dumb bets. And Buffett, with his trademark approach of cool rationality and hunting for bargains outside the major stock indices, was one of the first investors to realize just how many mistakes the average investor was making — and to bet a huge amount of money on that realization. Eventually, as more investors learned to be cool and rational like Buffett, his advantage over the market decreased.

If that’s the case, then as Jason Zwieg writes, there will never be another Warren Buffett. His basic approaches are probably still sound, but they will never again produce such stellar outperformance. Buffett defined an age that is now over.

2. Trump goes for price controls

During the 2024 presidential campaign, Donald Trump and his surrogates and allies railed against Kamala Harris’ flirtation with price controls. Now, Trump is declaring that he’s going to set prices on pharmaceuticals:

Whether Trump has the legal ability to do this is an open question; it could just be a populist move that gets blocked by the courts in a month or two.

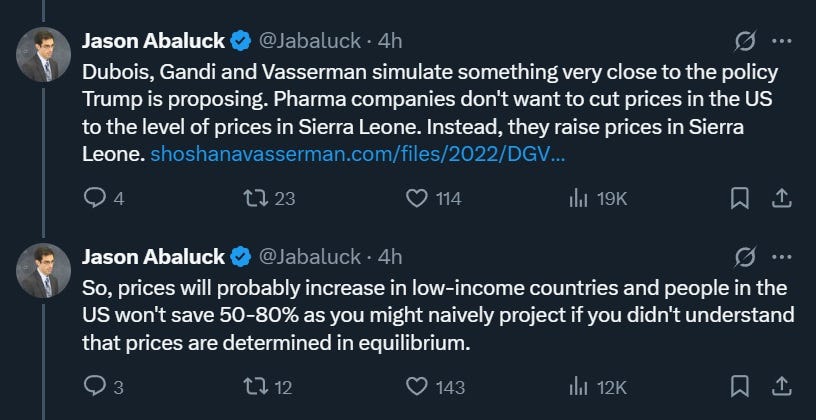

Even if the move does go through, it’s more likely to just raise prices in poor countries than to reduce them in America. If Trump mandates that drugmakers have to charge the same price in America that they do in poor countries, they’ll probably just mostly raise prices in the poor countries instead of lowering them in America:

So even if it goes through, the policy is probably going to fail in its goal of making drugs cheaper for regular Americans.

Of course, if drugmakers were forced to lower their U.S. prices by a huge amount, it would certainly help a lot of people in the short term. In the long term, however, it would probably lower medical innovation, by reducing the incentive to do long, arduous, expensive pharma research. A larger literature shows that the more revenue pharma companies make, the more they spend on research. Limiting these companies’ market size by limiting the prices they can charge will result in less research spending, and ultimately fewer new medicines and treatments.

Ji and Rogers (2025) find what looks like a recent example of this actually happening:

We investigate the effects of substantial Medicare price reductions in the medical device industry, which amounted to a 61% decrease over 10 years for certain device types. Analyzing over 20 years of administrative and proprietary data, we find these price cuts led to a 29% decline in new product introductions and an 80% decrease in patent filings, indicating significant reductions in innovation activity. Manufacturers reduced market entry and relied more heavily on outsourcing to other producers, which was associated with higher rates of product defects. Our calculations suggest the value of lost innovation may fully offset the direct cost savings from the price cuts. We propose that better-targeted pricing reforms could mitigate these negative effects. These findings underscore the need to balance cost containment with incentives for innovation and quality in policy design.

Here’s a thread Rogers wrote, summarizing the findings.

Some biotech entrepreneurs are already worried that this could hurt their businesses:

The biotech folks shouldn’t be too worried. As Abaluck shows, the likeliest result of Trump’s policy, even if goes through (which seems unlikely), is for Americans to be mostly unaffected while people in poor countries suffer.

But the precedent of Trump calling for price controls — another idea he cribbed from the left — shows that we’re sliding ever farther away from free-market capitalism, and toward a sort of boneheaded Maoism where economic central planning is done by a few very foolish old men whose ideas about economics all came from watching CNN in 1992.

3. More bad critiques of Abundance

When Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson published Abundance, a number of progressives rushed to attack it. Initially, most of the critics on the left argued that the authors had given insufficient attention to corporate power and the need for a movement against monopolies.

In a recent discussion, Klein pressed two of his progressive critics — Zephyr Teachout and Saikat Chakrabarti — to tell him what concrete problems they think an antimonopoly movement would solve. Again and again, Teachout’s answer is “power”:

It’s a democracy vision…I think for 40 years…we basically stopped asking the power question…[B]oth Republicans and Democrats got on board with…this idea that we should just focus on outputs and not on power. So that’s part of the reason you hear some resistance from the antimonopolists to your [abundance] vision.

Here we see the fundamentally different goals of abundance liberalism and anticorporate progressivism. Abundance liberals care about what stuff people get, while anticorporate progressives care about who holds power in society. The progressives have trouble explaining exactly how changing the distribution of power would lead to better material outcomes for the masses, but that doesn’t phase them much; to them, reducing corporate power is an end in and of itself.

As I’ve noted before, this ideas smacks of class resentment — a professional class that cares more about dunking on the entrepreneurial class than about helping the working class. That’s why critics of Abundance, like Aaron Regunburg, tend to focus so strongly on accusations that abundance liberalism is being secretly supported by class enemies:

Our concern is that corporate-aligned interests are using abundance to head off the Democratic Party’s long-delayed and desperately needed return to economic populism…[W]ho are the villains we should be naming? A growing number of Democrats are coalescing around a simple answer to that question: oligarchy…[M]any Democratic elites still oppose any attempts to identify billionaires and corporations as villains…[T]hey are terrified of the prospect of a populist takeover of a party…that has for decades served as a comfortable partner to oligarchy…

Groups like Third Way, which are largely funded by billionaires and corporations, have been major boosters of the abundance framework, as have other key pillars of US oligarchy, including crypto, Big Tech, and Big Oil. These interests have a clear vested interest in derailing the growing Democratic turn toward economic populism. And they have found in abundance advocates—like Abundance coauthor Derek Thompson, who recently argued that oligarchy “does a terrible job of describing today’s problems”—a valuable tool for redirecting the anti-establishment rage building within the Democratic base away from themselves[.]

This also probably explains why critics who claim to address the substance of Klein and Thompson’s arguments often seem not to have actually read Abundance at all. For example, the progressive economist Isabella Weber claims that Klein and Thompson call for deregulation but ignore the importance of state capacity in getting big things done. In fact, Klein and Thompson spend most of their book arguing in favor of increased state capacity, and bemoaning how progressives have focused their energies on shackling the power of big government. The most likely explanation for this mischaracterization is that Weber simply assumes that abundance liberals are allied with her class enemies, and thus must be simple small-government libertarians.

These critiques will find some purchase among progressives, including among the all-important Democratic staffer class (who I’ve now started to think of as the main audience for most of these factional food fights). But the critiques are fundamentally bankrupt. Companies, including large ones, have a crucial and indispensable role in providing the material living standards that make life in a developed country so good. There are no rich countries without big corporations. Of course if they capture the government it can cause big problems, but America’s progressives seem to think that the simple fact that corporations are large and profitable means that government has been captured. This is wrong, but class resentment makes it a compelling idea.

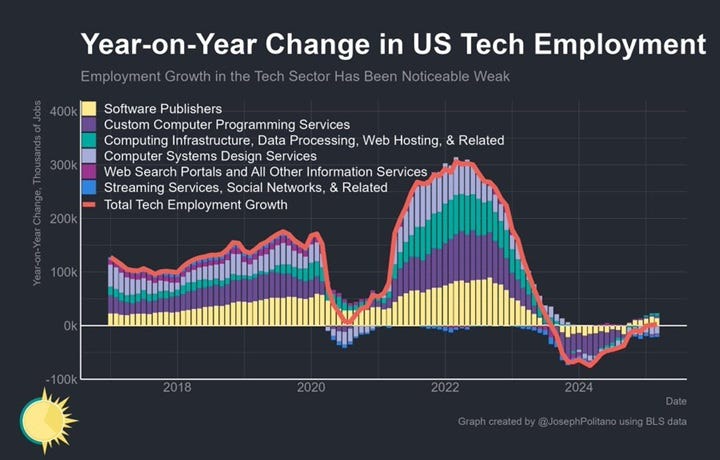

4. The continuing tech job bust

One of the most overlooked economic stories in America is the multi-year bust in tech hiring. In 2022, tech stocks crashed, but then eventually recovered. But the wave of layoffs that accompanied that crash never reversed — or at least, it hasn’t yet. It’s a brutal job market for tech workers out there:

Last year, I argued that this was because the internet has been mostly completed, leaving much less work for software folks to do:

Of course, AI has replaced internet software as the Next Big Thing — the locus of hype, VC investment, and engineer excitement. But it’s not clear just how many humans are going to be needed to build the AI future:

This chart seems like it probably should have included OpenAI, Anthropic, and xAI. Their total employment is a bit less than 10,000, and most of those folks have been hired in the last three years, so including them will moderate this picture a bit. Still, there’s no gigantic AI hiring boom to match the giant software hiring boom of the 2010s. No one talks about OpenAI as an omnipresent reliable cushy gig that a smart person can always go get a job at if their startup doesn’t work out, the way they talked about Google in 2018.

One possibility is that AI is already coming for software engineers’ jobs.1 AI basically does for software production what machine tools did for hardware production. If overall demand for software rises as a result of AI, then we’ll see an employment boom and a wage boom, but if demand remains constant and production gets automated, the industry will simply need fewer engineers.

In any case, I wonder if this protracted quiet tech bust is a significant factor in the emergence of the Tech Right. With the boom times over, and AI threatening disruption without making it clear where profits will be made, the software industry has gone from a gold rush to a defensive crouch. That might have scared some tech people in to thinking that only Trumpian deregulation, crypto-pumping, and special favors might be able to restore their wealth to its upward growth path.

5. Why British productivity stagnated

Why is the British economy so stagnant? The Resolution Foundation’s Simon Pittaway has an interesting new report that tries to answer that question. (Here’s a thread where he explains the report’s main findings.)

Pittaway shows how the U.S. has led the pack in terms of productivity, while the UK is falling behind:

Pittaway finds a number of problems that are probably holding back UK productivity, but his three main culprits are health, energy, and information technology.

The UK’s health industry has been dragging the country’s productivity down like no other:

Of course, productivity in the health sector is notoriously hard to measure, because the market is so un-market-like — value-added depends on how much people pay for health care, rather than how much actual value they’re getting. But including alternative estimates of health care productivity changes the overall picture very little.

It may be that the UK’s National Health Service is becoming less efficient.

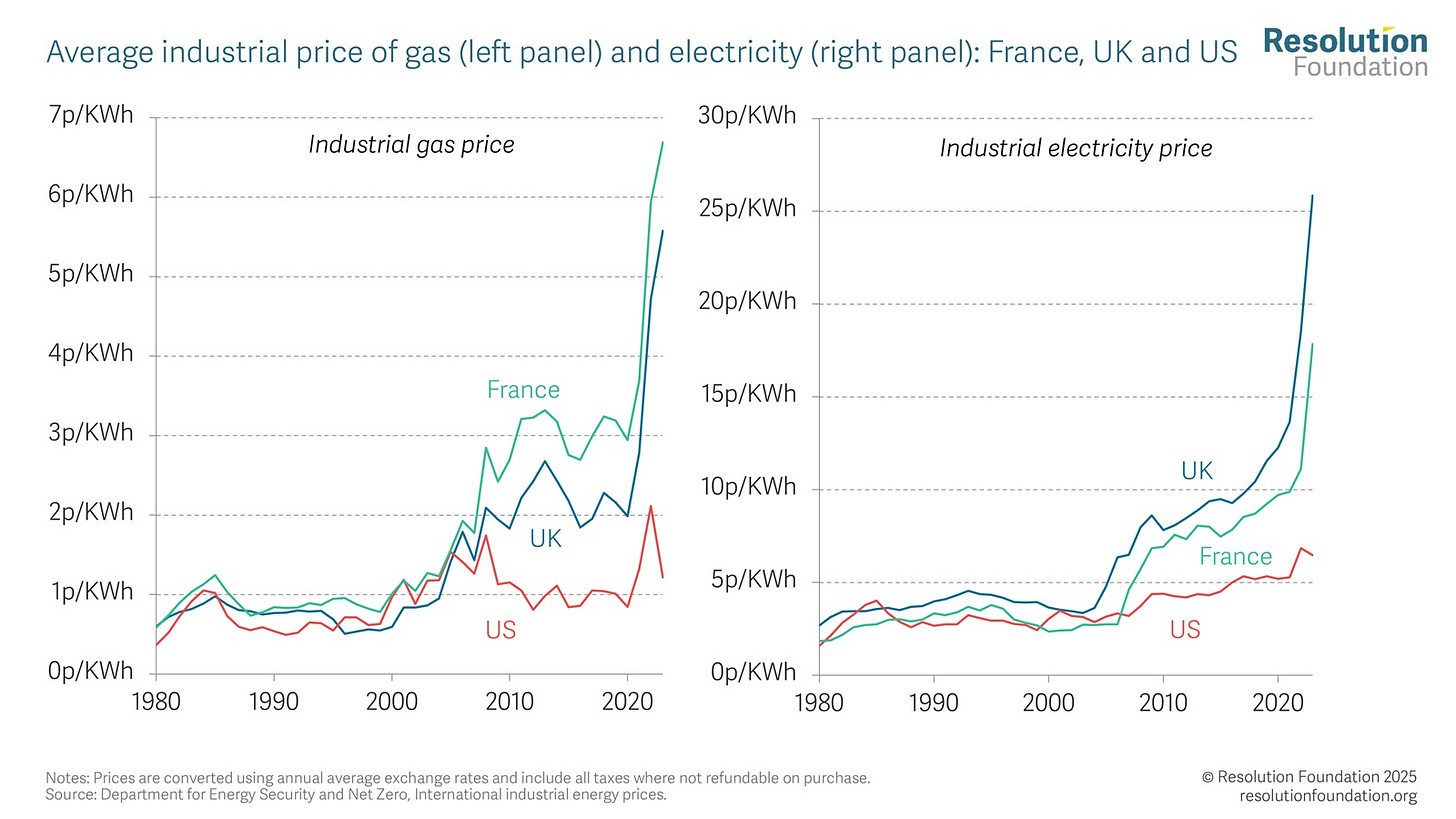

Anyway, Pittaway then notes that the U.S. has a lot more fossil fuel resources than the UK. This not only adds a big important industry to the U.S. roster, it lowers energy costs for American companies:

(As a side note, the fact that France’s energy costs have gone up as much as the UK’s, despite France mostly running on nuclear power, should serve as a wake-up call for people who think nuclear power can solve the UK’s problems.)

As for IT, Pittaway notes that U.S. companies purchase a lot more software than British companies do, for reasons that aren’t quite clear. To all this, add things like low business dynamism, disinvestment from Brexit, and so on. The problem of low British productivity is overdetermined — the country is just getting a lot of things wrong.

Although Pittaway is diplomatic in not pointing this out, a lot of these mistakes are probably politically driven. Brexit certainly was. The progressive antipathy toward fossil fuels, though rooted in very real concern over climate change, is probably overdone. And of course the NHS is probably shielded from reforms by politics. The UK, like the U.S., has fallen into a political equilibrium where popular ideologies push the country toward degrowth, and regular people just have to deal with it.

Correction: A previous version of the intro to this post stated that Warren Buffett is dead. He is not.

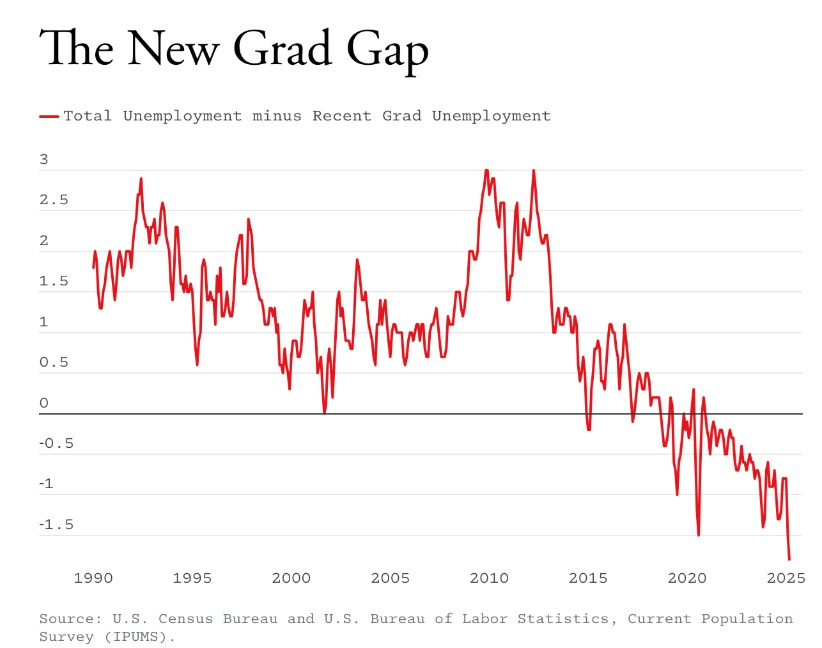

Derek Thompson argues that AI is already coming for the jobs of new college grads, noting that recent grads now have an unusually high unemployment rate:

I have to say I’m not convinced. AI wasn’t writing code in 2013-15, when the biggest rise in new grad unemployment occurred. A more likely story is that this chart reflects elite overproduction, though I suppose AI might have added a bit of fuel to the fire in the most recent year or two.

(As a side note, the fact that France’s energy costs have gone up as much as the UK’s, despite France mostly running on nuclear power, should serve as a wake-up call for people who think nuclear power can solve the UK’s problems.)

This isn't true. The cost of energy is determined by the cost of the *marginal* kWh. At the time scales we are talking about, the marginal kWh is nearly always from gas, because it's the only source of energy that can be practically scaled up within minutes to years. Nuclear takes decades to build, and hydrothermal, wind or solar aren't much better, and none of them can increase power within minutes or hours, so they provide mostly inframarginal kWh. Even if your country's solar is producing power for $0.15/kWh, businesses and homes are paying $0.40/kWh because that's the price that the gas plant operators are charging to put out the last, marginal kWh the grid needs.

Nuclear can make a difference to energy costs, but only on much longer timescales. This is also why energy costs are so high even in many places which are heavily adopting solar. The marginal kWh is still from gas. As long as this is so, Europe will be saddled with high energy costs until they find a different source of gas than Russia, or they move to a different source of marginal kWh, e.g. grid-scale batteries charged by solar.

"Warren Buffet is dead" made me do a double take!