At least five interesting things: Debunking the Debunkers edition (#73)

Basic income; Mississippi education; Nick Fuentes; Positive social trends; Botswana; Prison vs. mental hospitals; Building aesthetics; China brain-drain

I have some sad news to report: My podcast, Econ 102, is going on indefinite hiatus. Erik Torenberg, my excellent co-host, is very busy at his new job at a16z, and we weren’t able to keep up a regular schedule of podcasting. I apologize to all the fans of Econ 102!

Time permitting, Erik and I may return with more content later. And in the meantime, I am actively thinking about some other ways to deliver you voice and video content, so stay tuned.

In the meantime, here’s this week’s roundup of interesting econ-related stuff!

1. Another “L” for basic income

I had high hopes for the idea that just giving people cash would fix a lot of society’s problems. I still think a system of unconditional cash benefits would be simpler, fairer, and easier to navigate than many of our current welfare programs, and I still think it’s worth giving poor people money in order to make them less poor. But over the past few years, a bunch of new evidence has shown that the costs of cash giveaways are higher (in terms of incentivizing people to stop working), and the social benefits are much narrower, than boosters like myself had believed. Kelsey Piper had a great writeup of this disappointing evidence a few months ago, and I wrote up some thoughts in one of my earlier roundups.

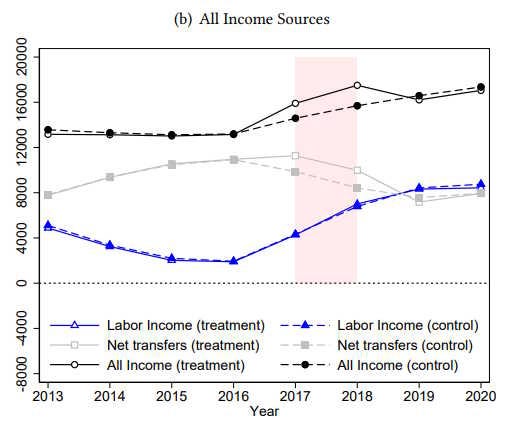

Now we have another piece of evidence showing that cash benefits solve fewer problems than we’d like it to solve. Aaltonen, Kaila, and Nix (2025) study a recent basic income experiment in Finland. In 2017, 2000 unemployed Finnish people were randomly selected to get a change in their welfare benefits. Instead of Finland’s usual unemployment benefits, the 2000 lucky people got 2 years of cash — about $658 per month at today’s exchange rates. This allowed them to A) keep receiving cash even if they started working, and B) avoid the normal job-search requirement that comes along with unemployment benefits.

The authors find that the basic income was effective in terms of raising people’s incomes. This isn’t surprising — if you don’t stop giving unemployed people cash when they get a job, they’re going to get more money overall.

Unfortunately, though, there wasn’t much impact on labor income relative to the control group. We’d hope that if we gave people money unconditionally instead of yanking it away the moment they got a job, it would incentivize them to go find work. But in this experiment, people who no longer faced that benefit cutoff were no more likely to go make money in the market:

That’s disappointing. But what’s also disappointing is the main result of the paper: People who received the basic income were no less likely to commit crimes. Aaltonen et al. write:

[W]e estimate the impact of being randomized to receive a basic income on crime perpetration. We find no effect on whether treated individuals perpetrate crimes. In the two years following the start of the experiment, individuals in the treatment group were statistically insignificantly 0.5 percentage points more likely to be suspected of a crime…representing a 2 percent increase relative to the control group mean of 20 percent…

We also find that the introduction of basic income had a statistically insignificant impact on the probability of being charged [with serious crimes] in district court…Over the two-year follow-up period, the point estimate suggests that the basic income experiment increased the probability of being charged by an insignificant 0.2 percentage points…corresponding to a 4 percent increase relative to the control group…

The results [also] show no evidence that treated individuals are more likely to engage in disorderly conduct, suggesting that the basic income intervention also does not increase lower-level criminal activity…

[W]e [also] find no evidence that introducing a basic income altered victimization risk…We also find no effects when we look separately by crime type.

In other words, giving people basic income instead of traditional welfare doesn’t seem to make them less criminal, and doesn’t seem to make them safer from crime. (If anything, it made people slightly more criminal, though the result wasn’t statistically significant, so “not noticeably different from zero” is the safest takeaway here.)

In other words, basic income has taken yet another “L” here. We’d like to tell ourselves that poverty is the root of crime, but in the short term, that’s not the case — giving people more money doesn’t make them less criminal, at least in Finland. The root causes of crime are either longer-term economic factors, or deeper sociological factors.

Cash benefits still give out cash, which makes people less poor. But they don’t have a lot of the side benefits many of us had hoped for. A lot of what happens in society can’t easily be reduced to how much money people make.

2. The Mississippi Miracle still doesn’t look like a myth

A couple of years ago, I wrote about Mississippi apparently achieving a breakthrough in teaching kids to read. From what I could tell, the improvement in fourth-grade reading scores was attributable to two things: improved teaching methods for reading, and a policy of holding kids back and making them repeat grades if they couldn’t read. I wrote:

I think there are basically two lessons we can learn here. First, older education techniques are sometimes better than newer ones, and deserve to be brought back (here is another example). Second, the progressive idea of giving struggling students more resources and the conservative idea of holding students back until they’re proficient at testable skills end up working very well together.

A few days ago, Andrew Gelman — generally one of my favorite debunkers of bad statistics — wrote a blog post about this so-called Mississippi Miracle, in which he chided me for not thinking about the selection effect of holding the worst-performing kids back:

[I]f you don’t let them pass to a higher grade, you’re gonna see higher average scores among the students who do take the test. This is something that an economics journalist should realize!

Well, yeah. I admit that I didn’t realize that holding some kids back could introduce a selection effect! I simply assumed that those held-back kids would take the test eventually, when they reached fourth grade, since A) every fourth-grader has to take the NAEP, and B) America doesn’t allow kids to drop out of school before high school.

So yes, I just assumed that the held-back kids were still in the sample of test-takers, and that holding more kids back wouldn’t distort the test results in Mississippi.

In fact, I still think I made the right assumption. Where does Gelman get the idea that some of the kids are being dropped from the sample? He gets it from a recent article by Wainer, Grabovsky, and Robinson that makes the same claim:

But it was the second component of the Mississippi Miracle, a new retention policy…that is likely to be the key to their success. Third-graders who fail to meet reading standards are forced to repeat the third grade. Prior to 2013, a higher percentage of third-graders moved on to the fourth grade and took the NAEP fourth-grade reading test. After 2013, only those students who did well enough in reading moved on to the fourth grade and took the test…It is a fact of arithmetic that the mean score of any data set always increases if you delete some of the lowest scores.

But why do Wainer et al. think the students who are held back end up being dropped from the sample of test-takers, instead of merely delayed to another year’s sample? It’s not clear. Kelsey Piper thinks Wainer et al. just haven’t thought very carefully about how education works in America:

[A] major plank of Mississippi’s reading reforms is a test of basic reading fluency administered at the end of third grade. Kids who don’t pass it are held back a year. For at least five years, people have argued that maybe this, rather than any actual teaching skill present in Mississippi, is what’s driving the state’s improvements.

A provocative new article from Howard Wainer, Irina Grabovsky, and Daniel H. Robinson in Significance argued that, in fact, nearly all of Mississippi’s results are driven by the third-grade retention policy, not by the phonics instruction, curriculum changes, or the teacher training that accompanied them. It has gone viral, with lots of glee in certain quarters, where it was sometimes taken as proof that there’s nothing other states need to learn from Mississippi after all…This is an important debate, but I’ve been dismayed to see their article treated as a significant contribution to it…

Strangely, [Wainer et al.] treated holding back 5% of students as identical to truncating the lowest 5% of test scores. But those are two different things, which makes their conclusion, that truncating the scores would be sufficient to explain Mississippi’s gains and therefore that other reforms played no role, invalid…

A student that repeats the third grade does not conveniently vanish off the face of the earth. They just … take third grade again, and then they move on to fourth grade. The state still tests them; they just do so a year later…If a student is held back a year, they still take the test again when they do reach fourth grade…Under Mississippi’s retention law, a student can usually only be retained for a maximum of two years.

They will still go on to fourth grade and therefore still take the test. This makes Wainer et al.’s entire analysis of how the mean shifts in a truncated dataset void.

What’s more, Piper digs into the Mississippi test score data — something that Gelman admits he didn’t do — and finds some very clear signs that the test score gains aren’t from holding kids back:

If all of Mississippi’s gains were from the bottom 10% of students being held back and then getting to take the test a year later…We would not expect the strongest students to be affected at all — none of them are held back, and almost no child is going to go from bottom 10th to top 10th in a single year…The NAEP publishes test scores broken down by decile. And what we see is that Mississippi has seen gains in every decile. [emphasis mine]

Now of course, switching to a policy of holding more kids back could temporarily juice scores for a couple of years, while the first cohort of weaker kids was being held back. But Piper notes that a lot of Mississippi’s test score gains came from well before 2015, when the policy switched. And she also notes that the gains haven’t been reversed since 2017, meaning that any illusory gains from that first held-back cohort are out of the sample by now.

Anyway, Andrew Gelman did apparently realize that the kids who are held back aren’t just dropped from the sample. At the end of his post, he writes:

I still wonder what happens with those kids who are held back and are then tested a year later. I guess they improve on average a lot on their own, no matter what is done, during that year.

But the kids who are held back are not “on their own”. They are still in school. And to claim that they improve “no matter what is done” doesn’t make sense, since all of them are still in school. So I’m not sure what Gelman is talking about here.

I’m not sure why Gelman, who is normally among the most perceptive thinkers when it comes to data issues like this, simply takes the conclusions of Wainer et al. at face value instead of interrogating their extremely questionable assumptions.1 Being a researcher instead of merely a journalist, he should dig into the data himself, and investigate whether there’s actually any reason to believe that the Mississippi Miracle is fake.

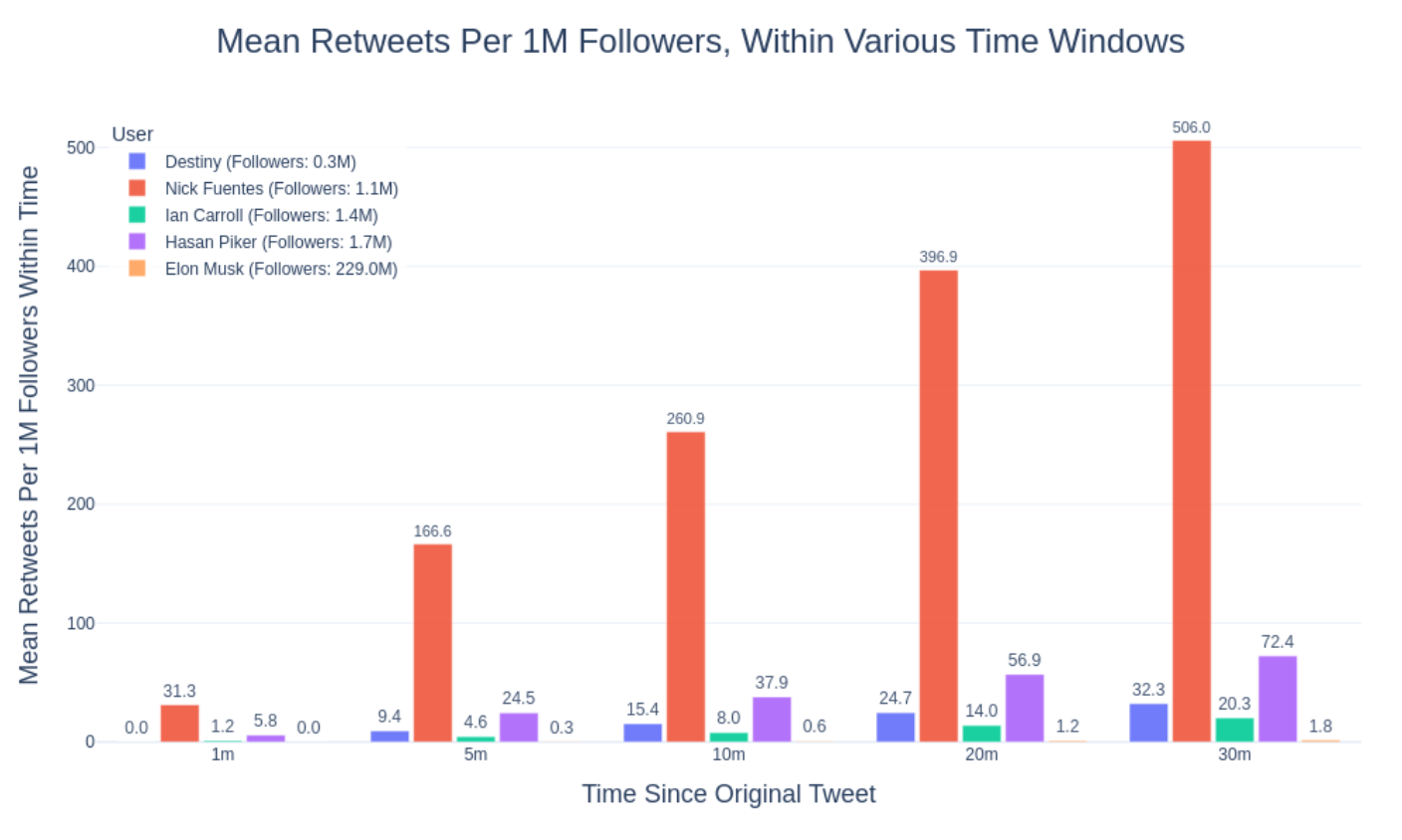

3. Someone out there is boosting Nick Fuentes

In the aftermath of the death of right-wing activist Charlie Kirk, there has been a lot of consternation that his shoes would be filled by Nick Fuentes. Fuentes is the leader of a movement called the Groypers that emphasizes antisemitism, ethno-nationalism, and various other race-war stuff. Richard Hanania has done a great job tracking how Groyperism has slowly taken over among the Republican staffer class, and among young Republican circles more generally. Fuentes is at the head of that movement, with his podcast briefly hitting the #1 spot on Spotify before being taken down.

A new study by the Network Contagion Research Institute has shown that Fuentes is being boosted by some shadowy, nefarious forces. Colin Wright, himself a man of the political right, has a good post explaining the findings:

Some key excerpts from Wright’s post:

According to NCRI, Fuentes’s apparent rise was driven by coordinated manipulation of online platforms, artificial engagement meant to boost his posts, and an information ecosystem in which major media outlets can be misled into thinking a fringe figure is suddenly influential…

The report’s most shocking finding is just how wildly Fuentes’s engagement numbers differ from those of other political influencers. NCRI compared the first 30 minutes of engagement on 20 of his recent posts with those from four major online figures—Elon Musk, Hasan Piker, Steven “Destiny” Bonnell, and Ian Carroll. Incredibly, Fuentes outperformed all of them in early retweets, including Musk, whose follower count is over 200 times higher…

None of this makes sense if the engagement is organic. According to NCRI’s report, this is explained by the fact that 61 percent of Fuentes’s early retweets come from accounts that repeatedly retweeted several of his posts within the same 30-minute window. This is not what you’d expect if these were random users scrolling their feeds. Rather, these accounts appear to be waiting for Fuentes to post so they could amplify his content almost instantly…

When NCRI dug into who these accounts actually were, 92 percent were completely anonymous. No real names, no real photos, no location, no identifiable personal information…When they examined Fuentes’s most viral posts—three from before the assassination of Charlie Kirk and three after—[NCRI] found that nearly half of all retweets came from foreign accounts, heavily concentrated in India, Pakistan, Nigeria, Malaysia, and Indonesia.

It’s not clear who is boosting Nick Fuentes. Pakistan, Nigeria, and so on are simply places where you can hire a bunch of people (and bots) to do artificial engagement-boosting. It could be any one of America’s foreign adversaries (all of whom Fuentes praises on his show), or it could be rightist rich people in America trying to boost their extremist ideology.

Either way, the proper takeaway here is NOT “Hahaha Fuentes’ popularity is fake, we don’t have to worry about Groypers taking over.” Fuentes’ popularity started out fake, but it didn’t entirely stay there — he got an interview with Tucker and has been covered by all the major media outlets, and his podcast soared in popularity (even if some of those downloads might be from bots). His ideas have probably been able to influence a significant number of young conservatives.

The proper lesson here is that new media technology — especially X and other viral media platforms — has tipped the scales of political discourse toward the worst extremists in our society. Unless and until we develop new institutions capable of gatekeeping out people like Fuentes, shadowy actors will use bots and paid engagement farming to boost them far out of proportion to whatever natural appeal their ideas would have had — thus destabilizing our democratic society.

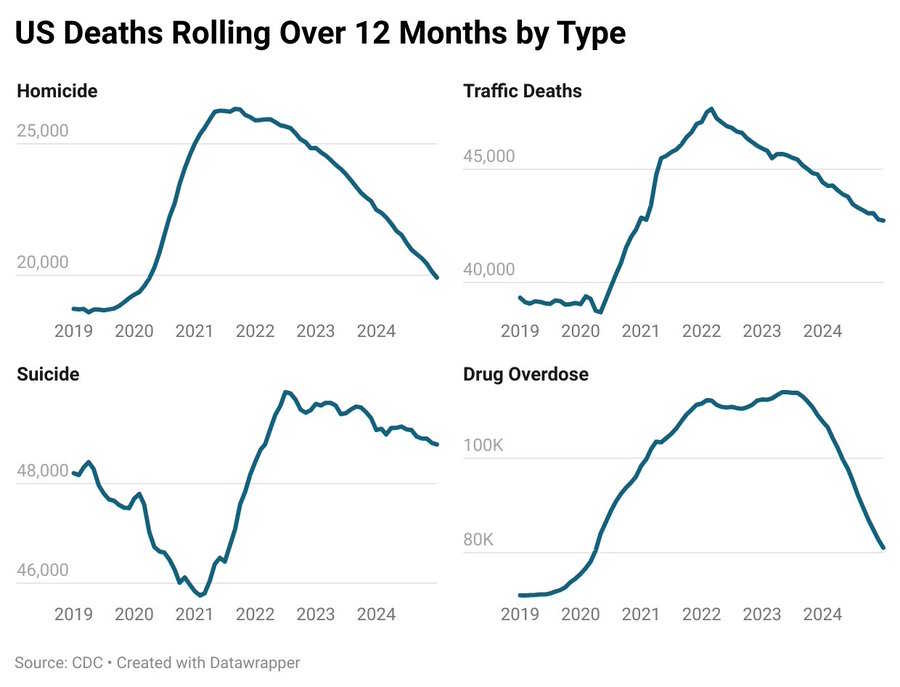

4. Good news about macrosociology

We hear a lot about worsening social trends in America — higher murder rates, more suicide, more drug overdoses, more traffic deaths, and so on. But it’s starting to look like a lot of that deterioration was just a temporary bump from the pandemic and/or the nationwide unrest in 2020. Jeremy Horpedahl recently posted a great chart showing that most of these trends have been reversing since 2022:

If these trends were due to specific policies — gun control, health care policy, drug enforcement, road safety policy — we wouldn’t expect them to line up so perfectly, and we probably would expect them to line up with changes in presidential administration or Congressional control. But they do line up, and the timing doesn’t seem to fit any political changes.

In other words, it seems like it’s possible for societies to just “break” and “fix themselves” in ways we don’t entirely understand. In other words, there is some sort of sociological macro-cycle out there.

Macrosociology?

5. Botswana is in big trouble

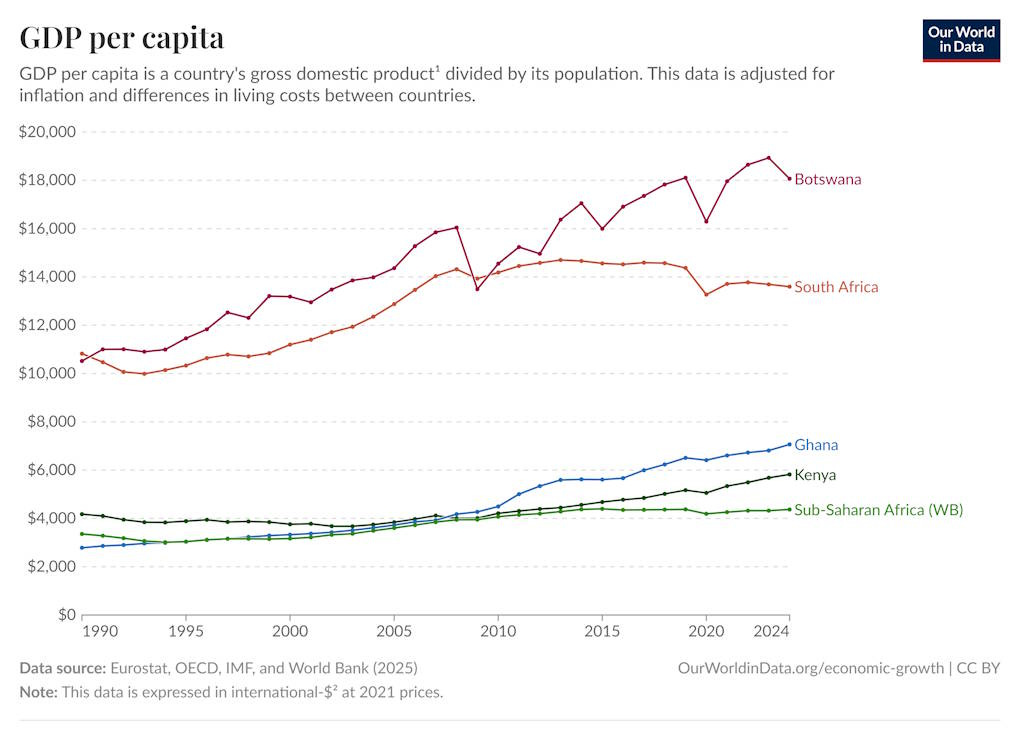

If you look at a map of per capita income, Botswana stands out from the rest of Sub-Saharan Africa. It’s not a rich country, but it’s comfortably middle-income, and does even better than South Africa:

Why is Botswana doing so well? Two reasons: Diamonds, and good policy. Botswana is richly endowed with diamonds, which represent the vast majority of the country’s exports. The country has slowly taken over the international diamond trade, including the company De Beers. And unlike many African countries, Botswana has funneled the money from its mineral exports back into constructive things like education and health. This is made possible by its high level of political stability, which may in turn be a function of its ethnic homogeneity (most Botswanans belong to a group called the Tswana). All in all, Botswana provides a hopeful case that poor resource-exporting countries can escape the dreaded Resource Curse.

But this success could now be under threat. Diamonds are valuable because they’re useful (they look pretty and have many industrial applications too), and because they’re scarce. But artificial diamonds are getting better and better, and soon even the highest-quality diamonds might not be so scarce:

Africa’s trade in natural diamonds [is buckling] under growing pressure from cheaper lab-grown diamonds mass-produced mainly in China and India…Diamond exports, roughly 80% of Botswana’s foreign earnings and a third of government revenue, have tumbled…In September, Botswana’s national statistics agency reported a 43% drop in diamond output in the second quarter, the steepest fall in the country’s modern mining history. The World Bank expects the economy to shrink 3% this year, the second consecutive contraction…

The global rise of synthetic diamonds has been swift…The gems emerged in the 1950s for industrial use. By the 1970s they had reached jewelry quality. Lab-grown stones now sell for up to 80% less than natural diamonds. Once making up just 1% of global sales in 2015, they have surged to nearly 20%…Lab-grown stones now account for most new U.S. engagement rings, he said. Natural diamond prices have fallen roughly 30% since 2022.

This demonstrates a fundamental principle of economic development: In the long term, countries do not become rich from digging up rocks. Humans are ingenious creatures, and we’re always figuring out ways to use resources more efficiently, to substitute common resources for scarce ones, and to use technology to imitate nature. If your country’s prosperity is based on rocks — i.e. on exploiting nature’s bounty in a straightforward, extractive manner — then human ingenuity is working against you.

Botswana’s experience should give pause to the lefty activists who believe that global poverty is due to rich countries exploiting poor countries for their natural resources. Botswana is basically the poster child for the idea that poor post-colonial economies can succeed by taking control of their rocks and selling them at higher prices in global markets. But their success only ever brought them to middle income, and now it’s under dire threat from technological innovation.

The real lesson here is that national wealth comes from ingenuity and hard work, not from sitting on top of rocks.

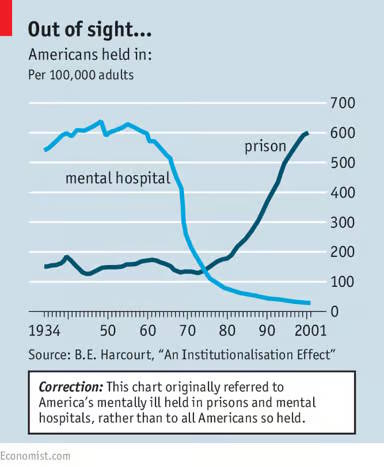

6. No, prison didn’t replace mental hospitals

Part of a pundit’s job is debunking viral charts. I wrote a two-part series on how not to be fooled by these charts. Today we have another example: the correlation between prison and mental institutions.

Have you ever seen this chart?

This chart comes from a 2013 article in The Economist, which got its data — and its thesis — from a 2011 paper by a law professor named Bernard Harcourt. But in an excellent recent post, Matt Yglesias dug into Harcourt’s papers and showed that the thesis just doesn’t hold up:

Yglesias points out that most of the people going to jail and prison in the 80s and 90s couldn’t have been the same people who were let out of mental hospitals, because a lot of the people in mental hospitals were white women or the elderly:

But (thanks to Xenocrypt for the tip) as Steven Rafael and Michael Stoll pointed out over a decade ago, the population in mental hospitals in 1950 was 87 percent white and 47 percent female. Twenty percent were over the age of 65 in an era when the aggregate population was much younger (only 8 percent of the public were senior citizens)…It is simply not the case that 40 percent of prison inmates are white women or 20 percent of crimes are being committed by senior citizens. We’re just not seeing anything remotely resembling a one-to-one substitution effect here.

Harcourt speculates that mental patients might be raising the crime rate by providing easy victims rather than by actually committing crimes, but Yglesias points out that this doesn’t make sense either, given what we know about victimization statistics.

Yglesias also notes that an earlier Harcourt paper made the much more modest claim that de-institutionalization caused between 4.5% and 14% of the rise in incarceration — in other words, not nearly enough to produce the viral chart.

It’s possible that some people did go from mental institutions to prison when we closed down mental institutions. But this was not the main reason for the rise in incarceration, or even a very big reason. The viral chart is just telling the wrong story.

7. Do Americans hate ugly buildings, or do they just hate buildings?

In the eternal quest to get America to build more housing, it’s important to take politics into account — we have to know how best to avoid activating the ire of local NIMBYs who block housing projects. If you post pictures of new housing online, lots of people inevitably pop up to say the new housing is ugly. And this concern is often raised at various public meetings as well.

But how real are the aesthetic concerns here? Are people just using architecture and style as excuses to block poor people from living near them, or to preserve their quiet streets? A pair of recent papers tried to answer that question by taking surveys, and came up with somewhat conflicting results.

The first paper is by Broockman, Elmendorf, and Kalla. Here’s a thread by Broockman explaining the findings. The authors surveyed people about when they would and wouldn’t support building new housing. Basically, they found that people are fine building more tall apartment buildings in places that are already dense, but oppose it in places that aren’t dense — even if it’s not their own back yard.

Why? The survey respondents said that cities “look nicer” without tall buildings. They also opposed the construction of office buildings, which the authors interpret as meaning that people genuinely care about aesthetics instead of just keeping poor people away. (I’m not so sure; downtown areas may also carry the connotation of being places where lots of poor people hang out.)

Broockman et al. argue that opposition to new buildings can be mitigated by making the new buildings look nice. They find greater support for building nice-looking buildings — the third panel in the pic, instead of the first panel:

I’m a little suspicious of these choices of photos; the first one shows not just an ugly building, but also displays some even taller buildings immediately abutting it, and also some cars on the street that indicate density. The third photo shows trees and gaps between structures, indicating a quiet street and low density. But in any case, the authors think this means that aesthetics matter a lot. They also find that support for building more goes up when they specify that the building would be designed by a star architect.2

Anyway, the second new paper, published just one day earlier, is by Pietrzak and Mendelberg. Here’s a thread by Pietrzak explaining their findings. They also survey a bunch of people about which apartment buildings they would like to see get built.

Two of Pietrzak and Mendelberg’s findings are very similar to Broockman et al. They find that people don’t like tall buildings, but that they support them more if they’re going to be put in neighborhoods that already have tall buildings.

But when it comes to actual building design, their findings were very different from the other paper. Pietrzak and Mendelberg found that there was no preference for traditional brick styles over more modern styles. And whether a tall building has the same style as the buildings around it also has almost no effect; people basically just don’t like tall buildings.

Taken together, these results convince me that Americans believe that tall buildings should be restricted to just a few neighborhoods. That will be an important attitude to overcome, since densifying the inner-ring suburbs will be necessary in order to build significantly more housing in America. But I’m not yet convinced that making buildings look nice makes any real difference to whether Americans will allow them. Further research on that question is needed, and there are probably some natural experiments out there with building code changes along municipal boundaries that could be used to tease out this effect.

8. Is China brain-draining America now?

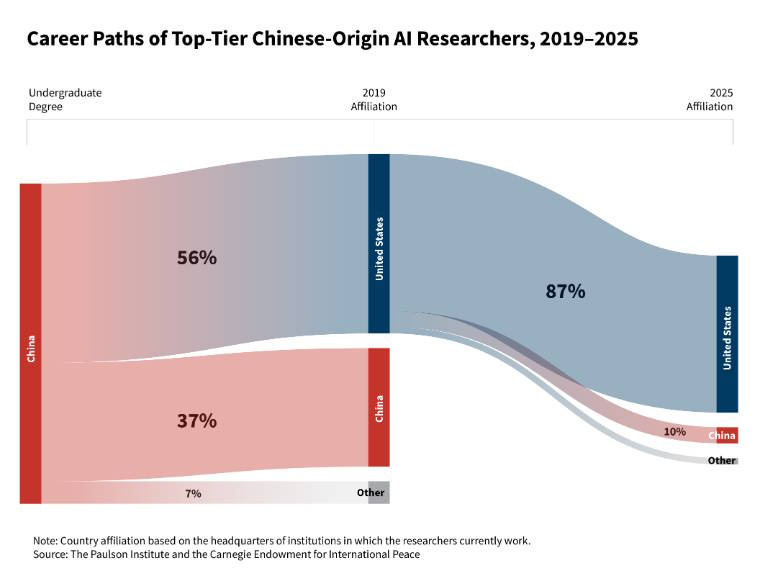

AI is the world’s most important industry, and China is the source of almost half of the top AI talent in the world:

Domination of the global AI industry is going to largely come down to which country can attract more Chinese talent. Until recently, America was dominating China in this race; most of the best Chinese AI researchers wanted to come and work in the U.S. There has been a lot of (justified) fear that Trump’s policies would reverse this advantage and drive Chinese researchers back to China.

According to a new report by the Carnegie Endowment, brain drain back to China has been very modest so far. Only a small sliver of the Chinese top AI researchers working in America has gone back to their home country since 2019:

The Carnegie Endowment report does highlight a few prominent researchers who have gone back to China, like Yang Zhilin. But so far these are the exception rather than the rule. And their return isn’t even necessarily due to Trump — China is pouring money into the AI industry, and companies like DeepSeek have emerged as real competitors to American industry leaders.

The Carnegie report explains that the bigger worry for the U.S. isn’t brain-drain — it’s that Chinese talent won’t even come here in the first place:

Although the United States has managed to retain a large portion of Chinese AI researchers over the past six years, there are signs that it has lost some of its ability to attract new arrivals from China—a potentially ominous trend given China’s share of global AI talent…

By [2022], Chinese-origin researchers made up nearly half of all the authors sampled, and Chinese institutions had more than doubled their share to 28 percent [since 2019]. That was still well short of the U.S. share of 42 percent, but it demonstrated rapid catch-up by China in producing many of the year’s best AI research papers.

Everyone seems to be sleeping on just how much China dominates the production of global top AI talent. If other countries can’t improve their own talent pipelines, their AI industries will continue to be dependent on luring Chinese people out of China.

Gelman also uncritically repeats Wainer et al.’s claim that Mississippi ranked 50th in the nation for 4th-grade math. In fact, as Piper points out, Mississippi actually ranked 16th. Wainer et al. simply made a mistake.

I’m a bit suspicious of this question too, as it might imply a ritzy, upscale area where poor people would be less likely to hang out.

I suspect that part of the reason so many people are skeptical of the Mississippi Miracle is that people outside of the south look down on Mississippi. We think of Mississippi as poor, ignorant, backward, and racist. If that's your view of Mississippi it's going to be hard to believe that they figured out how to get many more kids to become proficient I reading rather than say California. And if you're attached to the idea that Mississippi is extremely racist, you're not going to want to believe that it's doing a good job of teaching black kids to read.

Great post as usual!

1. Botswana is really in a bind. Duma Boko is trying to acquire a majority stake in De Beers, while De Beers is dying as a company. China's lab-grown diamonds are destroying the natural diamond industry. Debswana, the joint venture between De Beers and Botswana, saw revenues plunge roughly 50% in one year in 2024.

Natural diamonds are becoming what Peruvian guano or Chilean nitrates used to be: a has-been commodity that got replaced by the genius of engineering & science. (In this case, Lab-grown diamonds are the synthetic ammonium nitrate of yesteryear).

Frankly, Botswana has a problem where the main ways to be an economic elite in Gaborone either wants to secure government contracts for construction/consulting, work in a top civil service job, or be a rich cattle farmer. Botswana has a structural trap. Because Botswana relies so heavily on diamonds, the government collects almost all the money, meaning the government is also the primary customer for almost every business.

I wrote more about how China is crushing the natural diamond market here, if anyone wants more info:

https://yawboadu.substack.com/p/guns-germs-and-cobalt-q-and-a-9-insights?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=garki&triedRedirect=true