At least five interesting things: Build Something, Dammit! (#56)

Power vs. abundance; Chinese espionage; U.S. manufacturing woes; the growth of good jobs; Milei's successes

I’m in Taiwan this week for my annual New Year’s trip with a bunch of mostly tech folks from the Bay Area. The tradition began when a bunch of tech people moved to Taiwan to escape Covid during 2020 and 2021. Many of them go back every year to see the New Year’s fireworks, and for the past two years I’ve been tagging along. I’ll definitely write about the trip later — probably for my New Year’s essay.

But although I’m on a trip, I’m not on vacation! Even as I stroll through night markets and hike around the mountains, I’ll keep bringing you the content you crave!

First, here’s some audio content. I went on Yascha Mounk’s podcast to talk about the fall of “neoliberalism”:

And here are a couple episodes of Econ 102! We had culture writer Katherine Dee on as a guest, to discuss relationships and gender wars (two of Erik’s favorite topics):

And here’s an episode where I did a bunch of year-end Q&A:

Anyway, on to this week’s list of interesting things!

1. Power vs. Progress

While everyone is paying attention to the internecine battles on the right over skilled immigration, there’s a quieter struggle unfolding behind the scenes over the future direction of progressive policy. The two sides, which emerged during the Biden administration, might be called the “abundance” faction and the “power” faction. The abundance folks, who include writers like Ezra Klein and Matt Yglesias, believe that progressive economic policy should focus on delivering the American populace more of the things they want — more housing, energy, health care, and so on. Here’s what Yglesias wrote two weeks after Trump’s victory in November:

Democrats want and need to be a party that stands up for the little guy, for the person who, in Bill Clinton’s memorable phrase, works hard and plays by the rules. And that absolutely involves progressive economic policies…But contrary to the attitudes of the hard left, a growing and dynamic private sector is really important. Americans are much richer than Europeans, and that matters. Middle-class people tend to leave San Diego for San Antonio in pursuit of bigger, cheaper houses, and that matters. It also matters that poor people can get Medicaid in San Diego but not in San Antonio…

[Antitrust policy, for example,] is important precisely because it’s important to economic growth. And the same is true of plenty of other progressive ideas:

Investment in basic science

Good schools and good infrastructure

Internalizing pollution externalities

Transparent markets and rules against fraud

Macroeconomic stabilization policy

These things are important for growth and prosperity. There is a warm and cuddly side to progressive economic policy that’s about caring for the vulnerable. But there is also a tough-minded side that’s about true public goods and securing the commons…

The White House [under Biden] considered coming out for Jones Act repeal, but the president personally didn’t want to do anything that was anti-union. They took a look at the bipartisan permitting reform bill, and they weren’t exactly against it, but they also weren’t exactly for it, because they didn’t want to cross the environmental groups. They came out in favor of YIMBY principles, but they couldn’t come up with very much to do about it, because the federal government doesn’t run zoning.

And even while talking about housing costs, they raised tariffs on imported Canadian lumber. They reinterpreted the Waters of the United States rule in a way that homebuilders say is bad for supply. They put expensive rules in place to accelerate electric car adoption, even while alienating the owner of the world’s most important electric car company to please labor unions, while also alienating blue collar union members over cultural issues.

And Arnab Datta wrote a post for the New York Times arguing that climate activism needs to reprioritize results over sloganeering and ideology:

When Mr. Trump takes power, policymakers — as well as philanthropists, nonprofits and ordinary citizens passionate about climate change — must continue this strategy rather than revert to the old playbook of regulations, lawsuits and industry vilification…

Maintaining momentum also requires embracing priorities that might make some climate advocates uncomfortable, such as acknowledging that clean energy has to become much cheaper and more abundant to beat fossil fuels in the marketplace…

To bring prices down, Democrats will need to be open to cutting down on the endless red tape and environmental analyses required by laws like the National Environmental Policy Act, which, while established to protect the environment, is now making the process of producing clean energy needlessly cumbersome and expensive. Large nonprofit organizations can (and regularly do) sue agencies if they fail to consider even the most marginal environmental impacts of new energy projects, dramatically increasing the amount of time it takes to build anything new.

On the other side, the “power” faction thinks that the key question is who controls the Democratic party. They’re primarily focused on preserving and extending the hegemony of the progressive pressure organizations that have come to be called “The Groups”, and on preventing so-called “neoliberals” from steering the ship. For example, in a widely read post-election piece for The American Prospect, Dylan Gyauch-Lewis focused mainly on exposing connections between pro-abundance organizations and corporate interests:

Abundance is neoliberalism repackaged for a post-neoliberal world…

There are too many organizations pushing for the abundance agenda to break down comprehensively, but here are several that have connections to corporate interests:

The Foundation for American Innovation (FAI), which co-hosted Abundance 2024 and is listed as a key institutional partner by the Inclusive Abundance Initiative, was seeded by Charles Koch and is part of the State Policy Network. It has a track record of attacking unions. Politico reported on its work around a Silicon Valley conference as part of a “Venture Capital-Fueled Ideology.”

Institute for Progress (IFP), which co-hosted Abundance 2024 and is listed as a key institutional partner by the Inclusive Abundance Initiative, has a bevy of corporate ties. In 2022, IFP received $110,000 from FAI and has FAI’s executive director on its board. One of the founding funders of IFP was Emergent Ventures, which is a project of the Koch-backed Mercatus Institute at George Mason University. Emergent itself was launched by a grant from Peter Thiel. (Thiel is a right-wing billionaire with a vast influence network at the intersection of techno-futurism and anti-democratic thought who has called technology an alternative to democratic politics to “unilaterally change the world.” Vice President-elect JD Vance is a known scion of Thiel.)

Both co-founders of IFP also formerly worked at Mercatus. Another of IFP’s board members is a program associate at Mercatus. Other funders include Open Philanthropy, Stripe’s Patrick Collison, and Schmidt Futures—and used to include Sam Bankman-Fried. IFP is extremely pro-crypto; one of its founders suggested distributing unemployment benefits via crypto wallets, and the other has peddled Bitcoin as a solution to people being underbanked in the developing world.

Niskanen co-hosted Abundance 2024 and is listed as a key institutional partner by the Inclusive Abundance Initiative. In 2023, Niskanen received money from Google, Stand Together, and Arnold Ventures. Two Niskanen fellows also published the manifesto urging for the creation of an abundance faction within the Democratic Party.

Chamber of Progress, which self-identified its work as a part of “a growing ‘abundance’ policy movement,” is a trade group started with Google seed money by Google alum Adam Kovacevich. Kovacevich proudly touts his college activism of leading an effort to cross the United Farm Workers picket line. Chamber of Progress’s partners (read: funders) include a16z, Circle, Coinbase, Google, Kraken, Ripple, and Waymo. (Andreessen Horowitz, or a16z, is a venture capital firm heavily invested in AI and crypto. Co-founder Marc Andreessen believes that technology is the solution to every problem. He is also on Meta’s board.)

The abundance agenda is championed by figures like Ezra Klein (who, with Derek Thompson, will be releasing the book Abundance in the spring of 2025) and Matt Yglesias (a Niskanen senior fellow). It’s the “liberalism that builds” that Klein called for in The New York Times to replace what he derided as “everything bagel liberalism.” As the Prospect’s David Dayen noted at the time, though, growth and building require buy-in from key constituencies to amount to a durable movement. And the abundance faction is eager to sacrifice elements of the Democratic coalition. A key part of the Klein-Dayen argument was about not including pro-union conditions in things like semiconductor build-out.

I included this long block-quote from Rauch-Lewis’ article precisely because, as Ezra Klein drily noted, this is actually a pretty good list of groups you might want to listen to, or even financially support, if you’re left of the political center and you care about getting more stuff built.

It’s no secret which side of this debate I come down on. The “power” people seem obsessed with being the dominant faction in a losing coalition. Perhaps they think that thermostatic politics, progressive social movements, or some other outside force will win power for the Democrats, and that they’ll get to swoop in and redistribute the pie as they see fit. I suppose that’s sort of what happened in 2020 — Covid, and the distasteful rhetoric of the first Trump administration, allowed Democrats to pull off a narrow victory, after which the progressive “Groups” got to feed at the trough of power for four years. As a result, many of the Biden administration’s ambitious policies ended up fizzling.

I view this as a fundamentally parasitic approach. It’s a bit like Mao Zedong’s strategy against Japan in World War 2 — let the Nationalists do the bulk of the fighting against the invaders, then swoop in and take control afterwards. Instead of spending all their time knifing the abundance faction in backroom power struggles, I feel like the economic progressives should actually spend some of their effort fighting the Republicans and the right.

But the weakness of their basic case means that they will have trouble winning more power for The Groups in the court of public opinion. Americans as a whole are unlikely to support more requirements for government projects to use union labor or minority-owned contractors. Americans as a whole will be frustrated and enraged if they understood just how much NEPA and other regulations are weaponized by progressives to block the government from getting anything done. Therefore the only battles the “power” faction can hope to win are internecine fights against the abundance faction. And so, a bit like the leftists with their foreign policy obsession, the “power” faction spends much of their time fighting other Democrats and insisting on ideological purity.

This is why, in my view, the “power” faction needs to be ignored — and, if possible, marginalized. There’s a real opportunity for Democrats to become the party of abundance — even now, Republicans, who are beholden to their own NIMBYs, are starting to block permitting reform and other sensible solutions. And as Datta notes in the case of climate policy, this gives Dems an opportunity to build a coalition with a much broader array of interests:

Perhaps most important, the climate movement needs to build a broader coalition. Farmers have bountiful land that can be used to generate clean power. National security experts can make the case that we need to mine more critical minerals here in the United States, to avoid relying too heavily on China or other countries. And even fossil fuel companies can bring their expertise in drilling to bear on developing new technologies that would accelerate our transition to, say, geothermal energy. Climate action shouldn’t be the exclusive domain of environmental activists who pass a purity test based on intention, but instead on a pragmatic evaluation of what is required to make decarbonization good business, irrespective of politics.

This is why it’s important that the “abundance” faction win the internal fight to steer progressive policy over the next four years in exile.

Anyway, I think this is also a good place to post Thomas Hochman’s excellent reading list on permitting reform:

There is much to be done.

2. They see you when you’re sleeping, they know when you’re awake

One huge story that seems to have been almost lost in the flood of post-election political news is that the Chinese government hacked U.S. phone networks:

Chinese state-affiliated hackers have collected audio from the phone calls of U.S. political figures…The hackers are said to be part of a Chinese government-affiliated group that American researchers have dubbed Salt Typhoon. They were able to collect audio on a number of calls as part of a wide-ranging espionage operation that began months ago…They were also able to access unencrypted communications, including text messages.

This is the most stunning, brazen, wide-ranging foreign intrusion into Americans’ personal lives in modern history — at least, that we know of — and yet almost no one is talking about it. Most of the people whose calls and texts were intercepted by the Chinese have not even been notified. The true extent of the hack is still being uncovered, and it’s almost certainly not the only one of its kind.

When Edward Snowden revealed the extent of U.S. government surveillance of Americans a decade ago, it caused a massive popular uproar. But except for a few elites in the national security establishment, the nation seems to have collectively shrugged at the fact that an unfriendly foreign government has access to the personal conversations of the American people. It’s kind of mind-boggling that Americans would be more tolerant of the CCP reading their texts than of the NSA doing the same.

Are we really prepared to accept a world in which all of our most intimate personal details become the automatic property of the government of China? So far it seems like we are, but maybe if people pay more attention we’ll realize that that’s not a future we want. The obvious solution is to spend a lot more money on cybersecurity, have the government partner with top tech firms, and recruit a lot more software engineers to the fight against foreign intrusion. But with Trump showing little appetite for resisting Chinese surveillance — he’s actively trying to cancel the TikTok divestment bill — it’s questionable whether America has the will to protect its privacy.

3. U.S. manufacturing woes

China recently placed an order for a million kamikaze drones. Yes, you read that right: a million. There’s little doubt that China’s awesome manufacturing machine can fill this order, and in fact it’s just one small piece of a military buildup the likes of which has not been seen since World War 2.

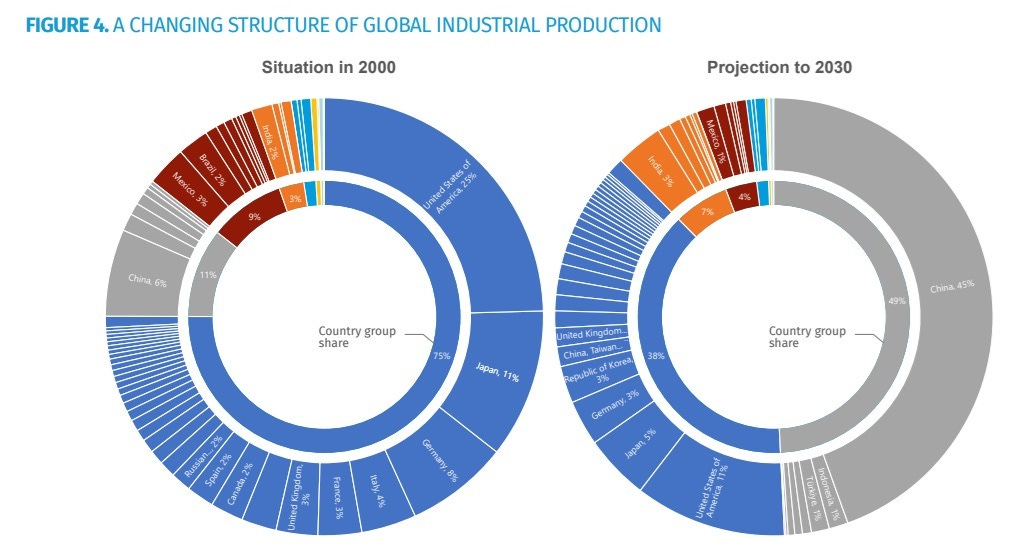

Losing control of global manufacturing has real consequences that have nothing to do with “good manufacturing jobs”. Let me once again post this chart:

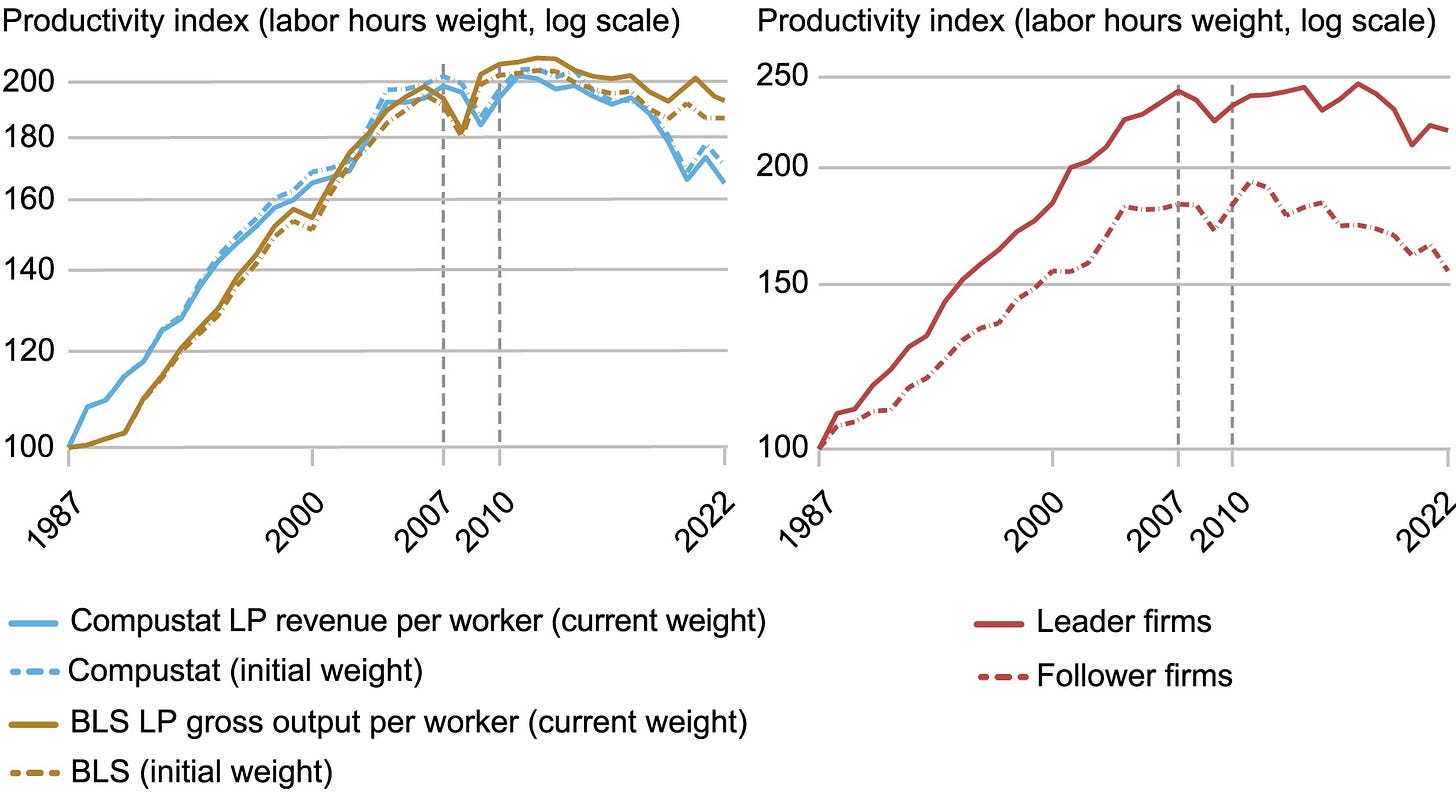

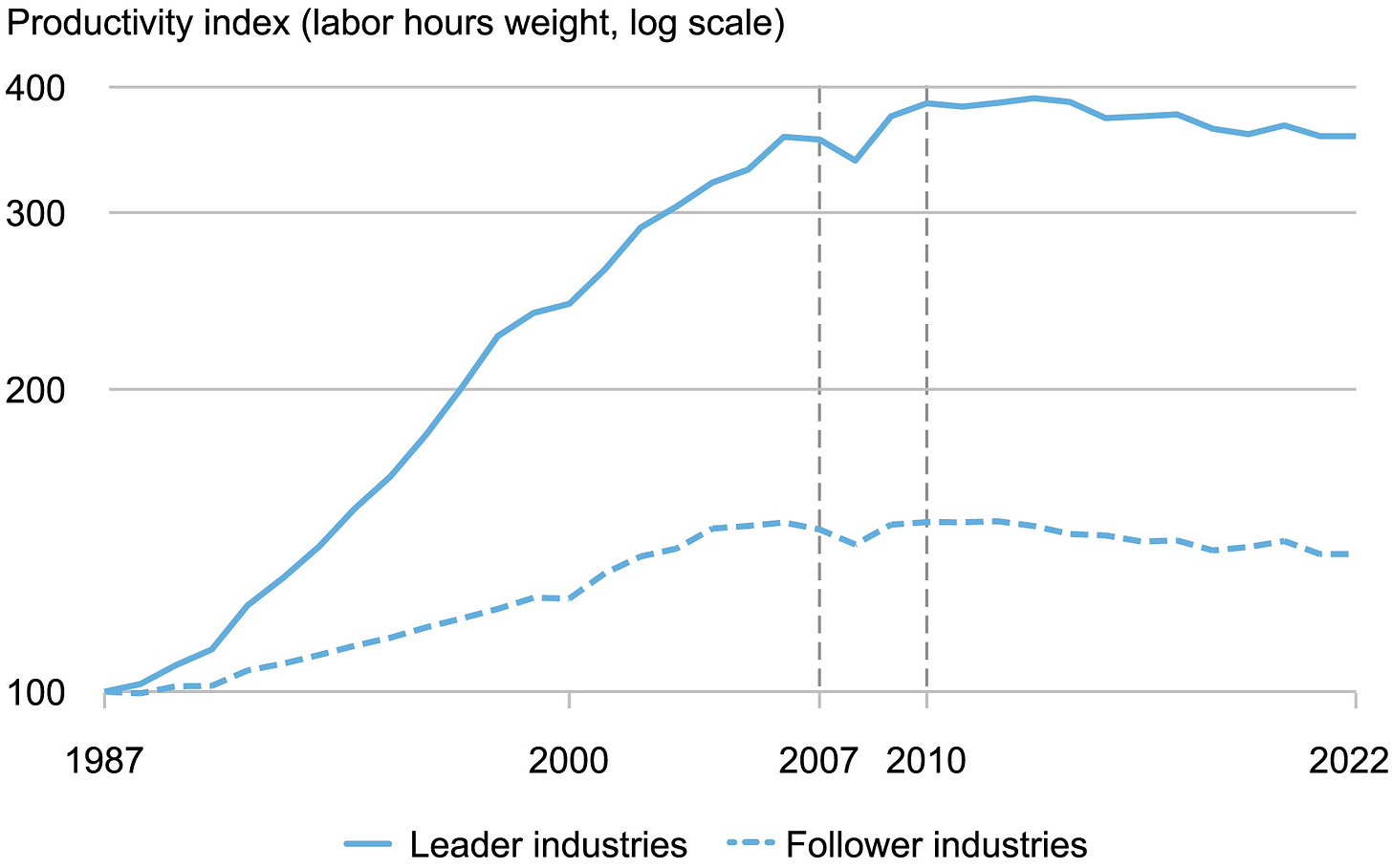

Meanwhile, U.S. manufacturing keeps going from weakness to weakness. Back in July I wrote a post about the mysterious slowdown in U.S. manufacturing productivity. Now Danial Lashkari and Jeremy Pearce have a post in which they show that the slowdown happened all across the sector — it wasn’t just a case of lagging companies falling behind the leaders:

It’s also not a case of some industries doing badly while others do well. The productivity slowdown happened across all U.S. manufacturing industries at the same time:

To me, this pretty obviously suggests something systemic in nature. And since a sudden slowdown in technological progress across all types of manufacturing industries seems implausible, the most obvious candidates are A) a change in the nature of outsourcing, trade, and globalization, and B) a change in the U.S. financial system that penalized manufacturing companies. As for what those specific changes might be, I need to do a little more investigation.

Meanwhile, Zane Hengsperger has a good long tweet about how the U.S. manufacturing ecosystem — a vast network of small manufacturers that supply the big ones — is rapidly withering and dying, with few entrepreneurs or new market entrants stepping in to take over. This should be a five-alarm fire for anyone concerned with American national power and freedom, and tariffs are absolutely not going to fix this on their own.

4. Good jobs are appearing

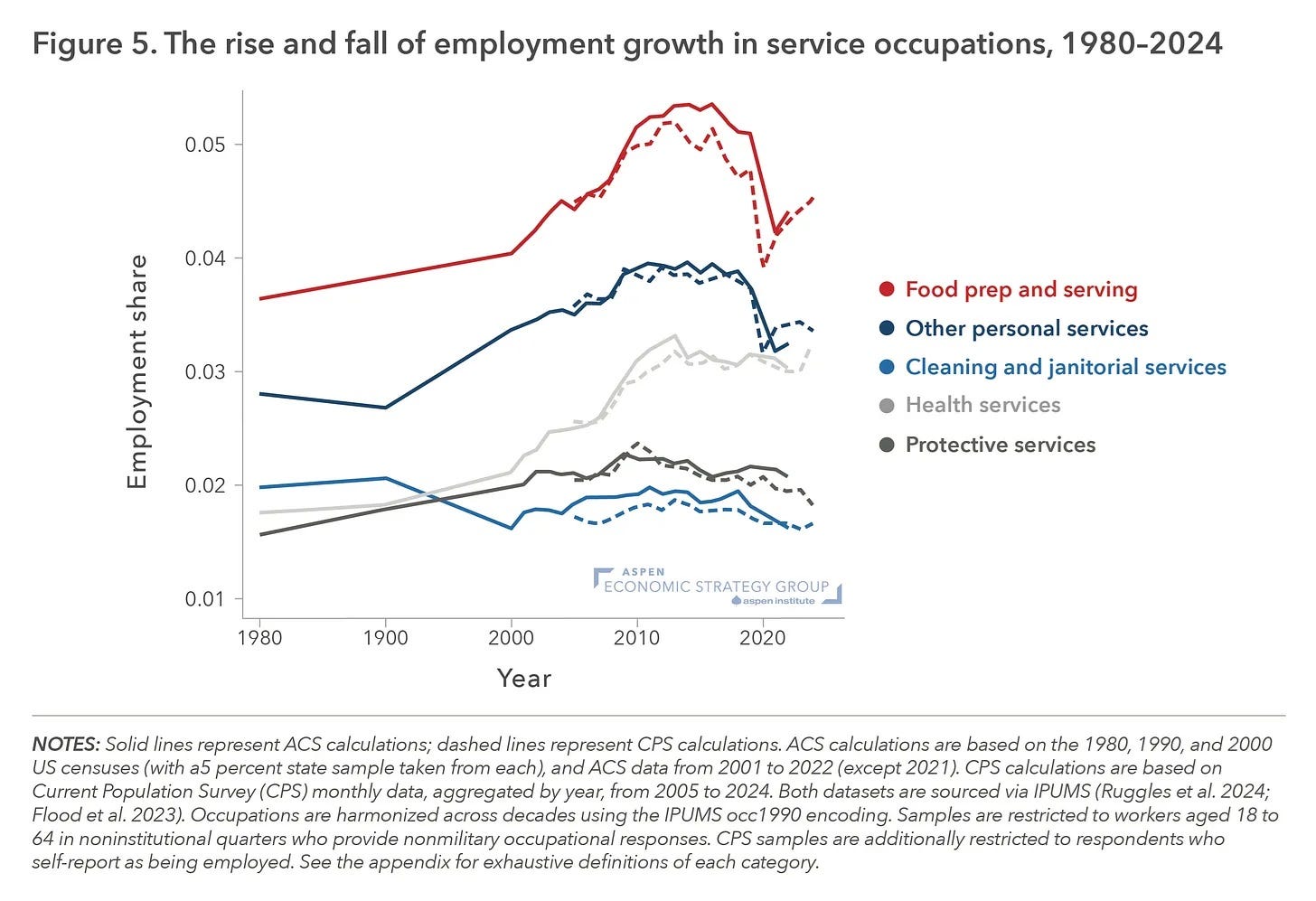

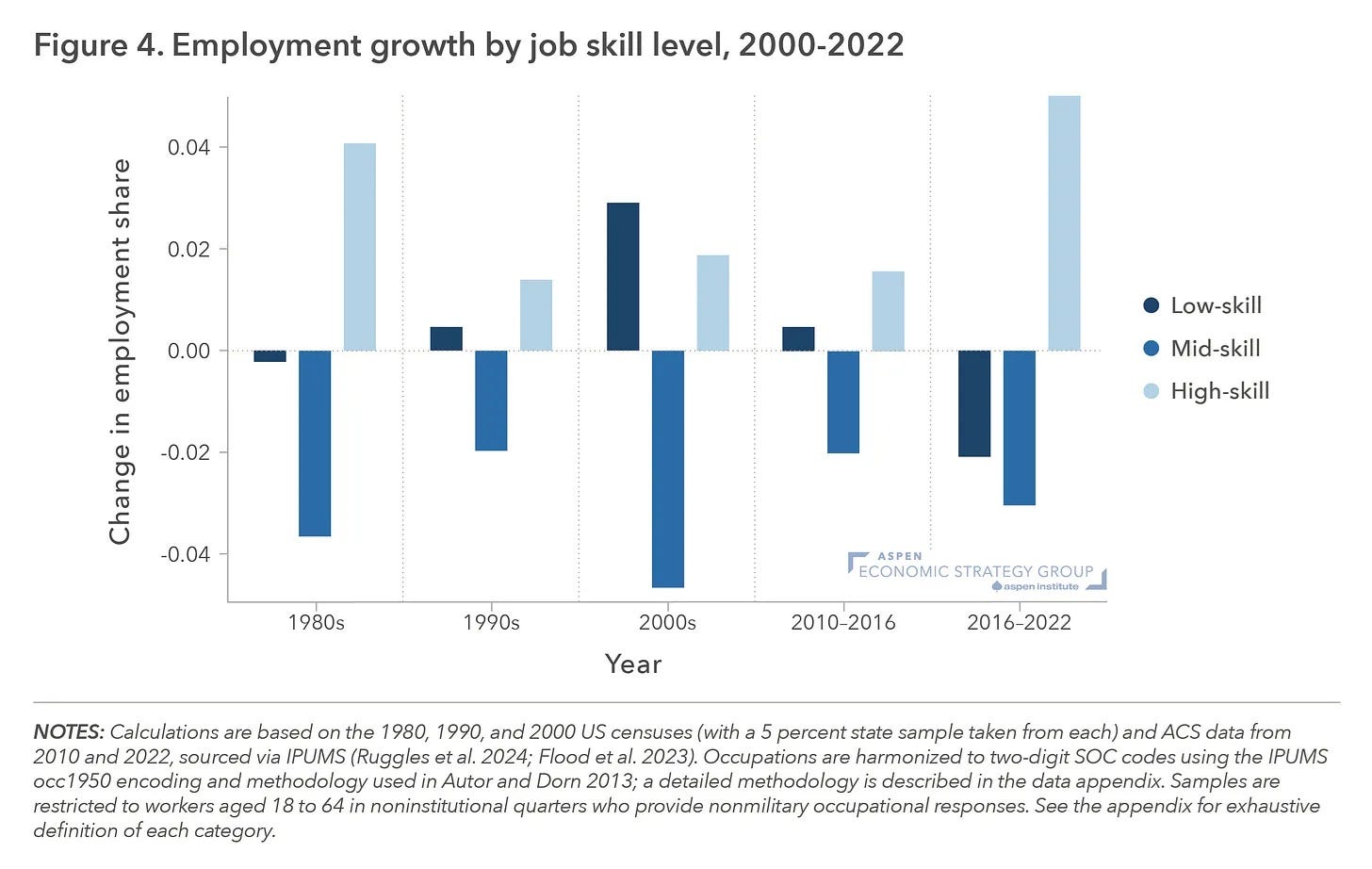

For years, Americans were bombarded with headlines about how “good jobs are disappearing”. Economists like David Autor found that the U.S. job market was polarizing — there were more low-wage low-skilled service sector jobs, but also more high-wage professional jobs. This raised the specter of an America bifurcated between an educated upper class and a hopeless downwardly mobile working class. That haunting vision animated many of the economic and political debates of the 2010s, as well as more recent discussions about the possible economic impact of AI.

But like so many big important trends, this one may have begun to reverse almost as soon as people started talking about it. David Deming, Christopher Ong, and Larry Summers have a new paper in which they show that low-skilled service jobs are actually becoming less common in America now, even as high-skilled professional jobs continue to grow. Here’s a good post that Deming wrote, summing up the results:

Here’s a great chart showing the decline in the low-skilled service-sector jobs that seemed like the future just a decade ago:

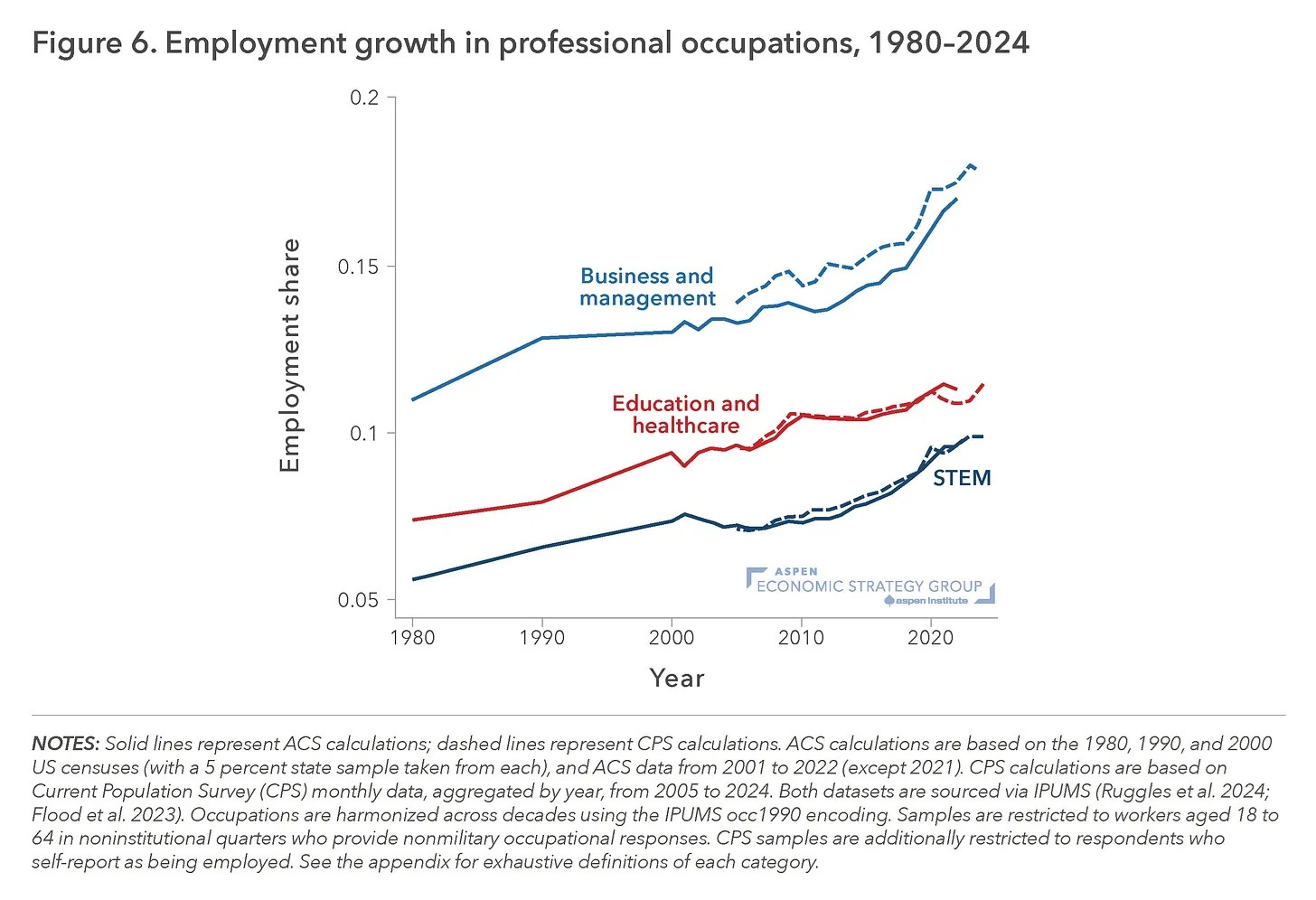

So what kind of jobs are growing? Good ones, in management and STEM — and, to a lesser extent, in education and healthcare:

In fact, high-skilled jobs are basically taking over from other kinds of jobs:

Crucially, this is happening even as America remains at full employment:

Basically, everyone in America still has a job of some kind, so it’s NOT the case that a bunch of working-class people are moving onto the welfare rolls as a result of the shift from low-skilled to high-skilled jobs. Instead, what’s happening is that since the mid-2010s, Americans have been simply moving up the job ladder en masse, with good jobs replacing bad ones.

This should cause us to update a few of our narratives about the American economy.

5. Milei seems to be doing well so far

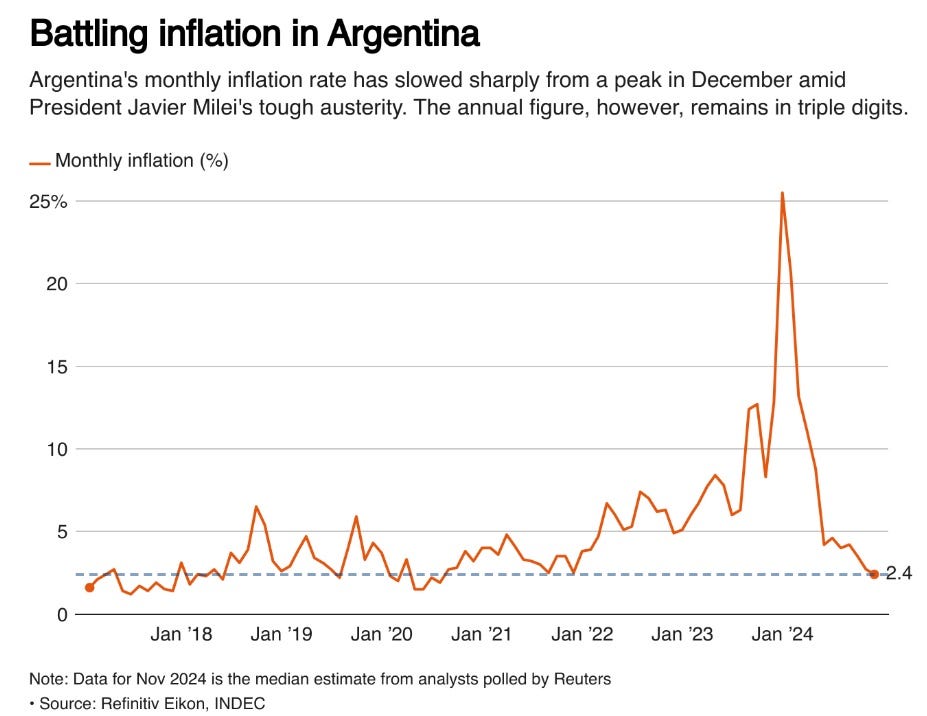

Progressive economists were horrified at the election of Javier Milei in Argentina in 2023, predicting all kinds of dire consequences for economic growth, the budget, poverty, etc. Even when I talked to Argentinians who favored free markets and fiscal austerity, they were fairly pessimistic about the chances that his flashy, reckless libertarian approach would succeed. Tyler Cowen gave him a 30-40% chance of success.

And yet while it’s much too early to declare victory for Argentina’s wild man, things are looking a lot more positive than most had dared to hope. Contrary to the warnings of the progressives, Milei succeeded in balancing the budget fairly quickly. Probably at least partially as a result of this sudden outbreak of fiscal probity, inflation, while still very high, has plunged:

As you might expect, fiscal austerity caused a recession. But the downturn appears to have been shorter and milder than many feared, and the country has already returned to growth, with the private sector leading the way:

Argentina emerged from a…recession in the third quarter…Gross domestic product expanded 3.9% from July to September compared to the previous three-month period, better than analysts’ expectations for 3.4% growth. From a year ago, South America’s second-largest economy shrank 2.1% in the third quarter, according to government data published Monday…

Capital expenditure, consumer spending and exports drove growth in the quarter, while public investment barely rebounded…

Signs of recovery are underway heading into 2025. Beyond the third-quarter growth, wages have surpassed inflation since April, job growth is slowly picking up and private estimates indicated poverty is gradually declining after spiking once Milei took office. Argentines also deposited over $20 billion in the financial system this year as part of Milei’s tax amnesty program, a robust sign of confidence in the libertarian president.

Longer term, Milei’s business-friendly reforms are starting to attract foreign investment commitments, particularly in the energy sector.

It’s way too early to be declaring total victory for libertarianism and building giant statues of Milton Friedman in downtown Buenos Aires. But Milei’s successes so far should make us consider the possibility that libertarianism has been underrated over the past few decades, especially in resource-dependent middle-income countries with macroeconomic instability.

#5 shouldn’t be such a surprise. We have previous examples in Chile and Peru. The next step in Argentina would be to codify some of these free market reforms -particularly central bank independence- to the constitution. But Id say this is just mainsrream economics . At the level of missmanagement Argentina experienced, there really isnt much difference between what Hayek or Milton Friedman or Larry Summers would do. Macroeconomic chaos has a big economic cost and also a big social cost. In Peru we have shared memories of going to the markets in the late 80s with parents and siblings so we could each grab two cans of milk due to rationing. Getting past this state of distopic normalcy and movimg onto a new normal injects a dose of positive emotions that fuel the economy. So yes, it is reasonable to see a short term shock that is relatively quickly overcome by an inflow of private investment and returns of expatriated capitals. After experiencing life under healthier macroeconomics, voters will have been vaccinated against irresponsible macro policy (although this is Argentina…so who knows). Eventually, there should be a leadership transition from a bulldozer type president that is focused on demolishing old institutions to a more centrist political class that will build uppn and manage the new statu quo. We have lived this before in Chile and Peru, so this shouldnt come as a big surprise. I will revisit this comment in a few years to check how well it aged. Argentina is second to none in drama so we will all have to wait and see..

It’d be great if someone somewhere did a piece on how cyber security works and why it’s so difficult to get all companies (small, mid, large) to take it seriously (dump money into it). MNCs resist top down regulations so the government is relegated to issuing guidance by EO. Proposals are often shot down because they duplicate rules, are too broad, etc etc.

And then people have the audacity to blame the government for the failure? Do these mammoth telcos not understand the myriad vectors of attack? Do they have any shame? Why don’t we just do two things:

- breaches must be reported within 72 hours to government

- compromised data will cause companies to incur fees/penalties/civil litigation

If we can’t do top down then we have to find an incentive to get all private actors to take it seriously.