At least five interesting things for the middle of your week (#7)

The decline of New Socialism, Europe's economic struggles, progressive power, manufacturing vs. finance, and a Japanese fertility experiment

The second episode of my new podcast Econ 102, with Erik Torenberg, is out! In this episode, we talk about the libertarian movement — why it fragmented, where it goes next, and why some libertarian ideas can help America do industrial policy. Here’s a Spotify link?

Here’s Apple, and here’s YouTube if you prefer to see my talking head.

Anyway, on to this week’s roundup of interesting stuff! Remember, if you’re a paid subscriber and you’d like me to add something to next week’s roundup, leave it in the comments.

1. The new socialist movement staggers to some sort of…something

In 2012 I joked that socialists in America were effectively invisible. By 2019, “abolish billionaires” had become a mainstream policy position. By 2021, people knew what a tankie was. The fall of communism had driven the socialist movement underground for a while, but in the late 2010s, buoyed by the Bernie Sanders campaign and by general social unrest, it came roaring back.

I never hopped on that bandwagon. I think the socialist movement of the 20th century did a lot of good for the world (and obviously ran off the rails in some places), but the 21st century version always seemed transparently ridiculous to me. The new socialists couldn’t seem to decide whether they wanted a fantasy of centrally planned abundance or a fantasy of degrowth; all that seemed certain was that they were dealing in fantasy. Everybody in the movement seemed to think Hugo Chavez was great, even after he and his cronies created one of the worst peacetime economic disasters the world has ever seen. Bernie’s economic program seemed like it was designed to be unworkable, a deliberately ephemeral fantasy crafted to ensnare the passions of a downwardly mobile educated Millennial “precariat”. The whole thing seemed completely silly.

In the early 2020s, the new socialist movement started to flounder. The Bernie campaign flopped hard in 2020, and the few “socialists” in Congress started to look like garden-variety progressives who were slightly less favorable toward Israel. Leftist figures like Noam Chomsky came down on the wrong side of the Ukraine war, and started to look like tankie sympathizers. Inflation stymied the dreams of the macroleftists who wanted unrestrained deficit spending. Everyone started to get frustrated with the Left-NIMBYs who would come up with any excuse to avoid building housing. A few of the Bernie people started flirting with the Right. Slowly, young people started to walk away from the movement.

This week’s discourse drove this home to a lot of people. Malcolm Harris went on a bizarre Twitter rant about how under socialism, we would not eat bananas:

A ton of people rightfully made fun of this, but a surprising number of socialists jumped out of the woodwork to defend the idea that banana consumption is unacceptable. Things got sillier and sillier, with one prominent banana opponent declaring that having fewer “treats” would make Americans appreciate life more, before revealing that she had a cocaine habit. Others mused that degrowth would enrich our lives by allowing us to take months of leisure time (not really thinking about who would pay for this vacation). If you want to read a more complete writeup of what happened, Eric Levitz has a good one.

All in all, this contretemps was a great deal of fun, because it made it very clear to a lot of people what many of us had realized for a very long time: the new socialist movement is a fundamentally silly thing. The idea that narcissistic shitposters should decide which commodities Americans are allowed to consume — and that this would somehow make life better for the developing-country agricultural workers who produce bananas as their means of livelihood — is so laughable on its face that it should force even those progressives who were deeply sympathetic to the Bernie campaign to reevaluate the idea that the new socialist movement represents anything remotely resembling a live political program.

There is a “steelman” case for the new socialist movement, which is that the idea of a “Green New Deal” might have focused the Biden administration on green industrial policy. The original GND was ridiculous in its particulars and was obviously just a way to backdoor a laundry list of new-socialist policy ideas, but the Inflation Reduction Act that it inspired is a serious and meaningful attempt to push the U.S. into the new energy era. Perhaps this would have happened without the Bernie people, or perhaps they came along at exactly the right time to nudge the Democrats into thinking that green industrial policy was what all the kids really cared about. It’s possible, anyway.

Overall, though, the new socialist movement seems to be staggering, if not to an end, than at least to some sort of well-deserved diminution.

2. South Europe is struggling; North Europe is OK

I’m generally not a big fan of Europe-vs.-America discourse. In general, all developed countries are about equally nice places to live; Americans enjoy higher material consumption than North Europeans, while North Europeans enjoy lower crime, longer lifespans, and more leisure. Both places have important things to learn from each other, and the frequent sniping that goes on about whose economic model is better could be more productively channeled into seeking out and adopting best practices in specific domains.

But over time it is possible for some countries or regions to fall behind so comprehensively that they no longer really fit into the top tier of developed countries. That’s why when I first saw this graph, it worried me greatly:

Europe has certainly endured three big shocks in the last 15 years — the euro crisis of the early 2010s, Covid, and then the cutoff of Russian natural gas. Quite apart from any consideration of Europe’s social model or industrial policy, it’s reasonable to worry that these shocks proved too much to endure.

But thinking about this chart a bit, I’m less concerned than at first glance. 2008-2019 is a much longer period than 2019-2022, and the latter involves a lot of short-term disruptions. When we look at 2008-2019, we see that Germany and France saw very substantial wage gains — on par with the U.S. — while the UK saw modest gains. The last three years don’t concern me as much.

Let’s look at somewhat clearer chart: the difference in per capita GDP growth since 2008:

You do see a bit of divergence here between the top performers — the U.S., Sweden, and Germany — and the middle tier of the UK, Switzerland, France and the Netherlands. But the cumulative difference between these groups is not that large, and about half of it just looks like Covid.

(And no, the difference between median and average is not going to be a big deal here, since inequality would have to change by vast amounts in a very short space of time in order for median and mean to tell substantively different stories.)

But when we look at the graph — or at the WSJ’s chart above — we notice that the South European countries have done much worse than anyone else. Spain, Italy, and especially Greece have not yet recovered from the financial crisis, and Italy and Greece hadn’t recovered even before Covid. Greece is more than 20% poorer than it was a decade and a half ago. That’s economic development in reverse.

My general conclusion is that we need to focus less attention on what Germany or France is doing wrong relative to the United States, and focus more attention on what South Europe is doing wrong relative to North Europe. Expect some posts about that in the near future.

3. Progressives can’t build power if they don’t build success

Ezra Klein, one of the champions of supply-side progressivism, has taken some heat for urging progressives to prioritize material abundance over special interest groups. On the right, conservatives like Reihan Salam have argued that progressivism is simply a gaggle of special interests looking for their own slice of the pie, so the changes Ezra wants can never happen. On the left, progressives like David Dayen maintain that increasing the power of Democratic-aligned interest groups should be a major goal in and of itself.

In a recent post, Ezra defended himself adroitly from both sets of critics. In response to Salam, he points out California’s YIMBY turn as evidence that supply-side progressivism is politically viable:

Policy is changing. Just look around.

Berkeley, Calif., was the first locality to mandate single-family zoning. In 2021, the Berkeley City Council voted to end single-family zoning…California followed suit, passing a bill that functionally outlawed single-family zoning across the entire state. In San Francisco, Mayor London Breed recently proposed reforms to the way housing is built in the city that delighted even the most hardened of YIMBYs. In Los Angeles, voters raised taxes on themselves to address homelessness and Mayor Karen Bass and the City Council just exempted affordable housing from a lengthy step in the planning process.

Statewide, Gov. Gavin Newsom has now signed more pro-housing bills than I can reasonably describe here, and he just passed a package of permitting and procurement reforms over the initial protests of environmental groups. And it’s not just California: Oregon and Maine also outlawed single-family zoning, and Connecticut and Massachusetts have taken steps in the same direction.

This is true, and it’s important to remind progressives who are wondering whether to embrace Ezra’s program that abundance can win. But Reihan is really talking to conservatives; he’s telling them not to worry about the idea that industrial policy represents a new economic policy paradigm that will take us past the old Reaganomics. This is a dangerous message, since it lulls conservatives into thinking that they can skate by without a real economic policy program, simply flogging yet more tax cuts and the fantasy of eliminating random government agencies. Conservatives need to do better than that; they need to craft their own vision of industrial policy, and make it their own, or risk being left behind, because the fundamental challenges that motivated the shift to industrial policy (China, climate change, the housing shortage, excess costs) are not going away on their own.

Ezra then addresses Dayen’s argument, rebutting various claims that Dayen makes about energy and housing. Here is what I consider to be Ezra’s most important point:

In focusing on how power can be gained, [Dayen] is ignoring the very real way in which it can be lost. Power is lost when projects fail — and it is lost by the very interest groups Dayen wants to defend.

If union labor and Democratic governance are seen by the public as reasons that needed infrastructure remains endlessly unfinished and relentlessly over budget, that will, eventually, lead the public to demand alternatives. The result will be the outsourcing of public services to private companies and the election of new politicians who will pass laws designed to limit the ability of labor to organize.

If progressive industrial policy ends up delivering more power to unions, NEPA lawyers, etc., but not actually building more energy and housing and semiconductors and such, voters will — quite rightfully — conclude that the whole thing was a scam to seize power. They will then vote for Republicans.

A lot of progressives think this just can’t happen — that there are no such thing as swing voters, that identity drives everything, and that Democrats’ only electoral concerns should be A) turning out the activist base, and B) waiting for more conservative generations to die off. This is snake oil. It’s the same snake oil Karl Rove sold to Republicans in the 2000s, which led to their losses to Obama. Again and again it gets proven false at the polls — swing voters exist, and persuasion is important.

“Just turn out the base” and “demographics = destiny” are two of the most poisonous ideas in American politics.

Anyway, progressives like David Dayen should realize that you can only build power in a democracy if you build success as well. If you don’t provide benefits to people far outside your favored interest group base, you will not be able to assemble a broad winning coalition. But if you do provide the country at large with tangible benefits, you will be able to build power for your favored interest groups. This is what FDR did; the New Deal, despite some mistakes, was broadly successful, and the WW2 mobilization was wildly successful, and this is what gave progressives the political clout to make union power an institution in mid-century America. That should be the model for success now; don’t grab for power before you figure out how to actually build.

Some evidence for manufacturing over finance

In a post last week, I argued that the main point of America’s embrace of industrial policy isn’t about manufacturing being better than other types of economic activity — it’s about stopping climate change and standing up to Chinese military power. There are potential economic benefits of boosting advanced manufacturing — clustering multiplier effects, increased productivity, and so on — but these require more evidence to weigh the costs and benefits.

That said, there is another justification for a manufacturing-focused industrial policy that I didn’t really touch on in that post. In their excellent book Concrete Economics: The Hamilton Approach to Economic Growth and Policy — which you should absolutely buy and read if you haven’t yet — Brad DeLong and Stephen S. Cohen argue that a country that tries to have no industrial policy will end up having a finance-based industrial policy. The argument, in a nutshell, is that if the government just throws up its hands and says “the market can decide what industries we need”, then the task of actually deciding what industries we need will fall to financiers. And the financiers, as middlemen, will take a hefty cut. So by stepping back from the industrial policy game, government is essentially privatizing it, and finance does it for a much higher price.

If you believe that finance is always much better than the government at doing the job of allocating capital between industries (at least on the margin), then maybe this doesn’t bother you — sure, the private equity people and big bankers and hedge fund managers are getting rich, but they deserve to, because they’re so much better than anyone else at seeing where the best growth opportunities lie and making sure that resources get funneled there. But if you think that there’s something inherently wrong with the finance industry — that it mostly extracts rents instead of boosting productivity — then you won’t see financialization as the best path. The idea isn’t that finance is useless as an activity, just that there tends to be a bit too much of it on the margin when government doesn’t act as a countervailing force.

A new economic history paper lends a bit of weight to this second hypothesis. In “Credit Allocation and Macroeconomic Fluctuations”, Karsten Müller and Emil Verner look at why credit booms are often followed by economic busts (as in America in 2008). They conclude that the culprit is that credit booms usually — but not always — tend to redirect resources toward the non-tradable sector, which results in lower productivity growth:

We study the relationship between credit expansions, macroeconomic fluctuations, and financial crises using a novel database on the sectoral distribution of private credit for 117 countries since 1940. We document that, during credit booms, credit flows disproportionately to the non-tradable sector. Credit expansions to the non-tradable sector, in turn, systematically predict subsequent growth slowdowns and financial crises. In contrast, credit expansions to the tradable sector are associated with sustained output and productivity growth without a higher risk of a financial crisis. To understand these patterns, we show that firms in the non-tradable sector tend to be smaller, more reliant on loans secured by real estate, and more likely to default during crises. Our findings are consistent with models in which credit booms to the non-tradable sector are driven by easy financing conditions and amplified by collateral feedbacks, contributing to increased financial fragility and a boom-bust cycle.

In other words, an over-financialized economy tends to shove money at industries that are weaker in the long run (mainly real estate and related stuff), which creates busts. But directing money toward the tradable sector — which is mostly manufacturing — tends to result in long-term healthy growth.

So if we don’t do industrial policy, banks and other finance companies might just swoop in and pump all of the money in our economy into crappy real estate, looking to make a quick buck, and leading to an eventual 2008-style crash. Then again, China’s current real-estate-driven slowdown shows that it’s very hard for manufacturing-based industrial policies to swim against the tide of financialization, even when the government is very powerful. But still, something to keep in mind.

Japan, fertility, and work-life balance

Falling fertility rates are an incredibly widespread issue, and no country has yet figured out how to reverse the trend. Japan has been dealing with low fertility for longer than most countries, and has a history of coming up with innovative policy solutions, so it’s interesting to see what they try. Bloomberg’s Kanoko Matsuyama has a very interesting story about a Japanese trading company (which these days is basically sort of like an investment bank plus a PE firm) that seems to have hit upon something that might help.

Basically, Japan has a broken corporate culture that values hours worked rather than productivity. A Japanese exec at Itochu came in determined to break that antiquated system and switch to a culture that emphasizes getting things done — basically by making people go home at a reasonable hour instead of staying at the office all night.

You’ll never guess what happened next:

When Masahiro Okafuji became chief executive officer of Itochu Corp. in 2010, he made improving productivity a top priority so the company could compete against bigger rivals in Japan. His approach was counterintuitive. Working in the office after 8 p.m. would be banned, and there would be no more overtime—with rare exceptions. Security guards and human resources staff would scout Itochu’s office building in Tokyo, telling people to go home. Those clinging to their desk were told to come in early the next day to get their work done—and get paid extra.

The tough love worked. A decade later, the company…reported a more than fivefold jump in profit per employee from 2010 to 2021…What also changed, to the surprise of Itochu’s management, is that more female employees took maternity leave, had kids and came back to work.

Here’s the key chart.

It might seem weird to compare the fertility rate of one company with the fertility rates of whole countries, but in this new Children of Men style world we find ourselves living in, we’ll take what we can get. The next questions will be whether this sort of intervention can A) replicate at other companies, B) scale up to society as a whole, and C) persist for long periods of time. That’s a tall order, so we’ll see. Lots of European countries have great work-life balance and still have very low fertility rates. But it’s something worth investigating and adding to the toolkit.

From the comments:

6. Does minimum wage increase homelessness?

Joe Lynch asks for my take on this article by Megan McArdle:

I want to introduce a new argument: that higher minimum wages may be contributing to homelessness…This suggestion comes from Seth J. Hill, a professor of political science at the University of California San Diego, who recently published a striking analysis of cities that raised their minimum wages between 2006 and 2019. He found that in these cities homelessness grew by double-digit percentage points. The effect was larger for cities with bigger minimum-wage increases, and it also appeared to get stronger over time.

So, the first thing to point out here is that the only plausible way for minimum wages to increase homelessness is by increasing unemployment. It’s basically just: minimum wages go up —> companies can’t afford to keep as many workers —> layoffs —> people can’t afford rent so they go out on the street. That’s it. That’s the mechanism. There’s no other plausible way you get from minimum wage to people sleeping on the street.

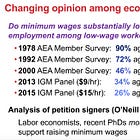

So the question of whether higher minimum wage causes homelessness is really just the question of whether higher minimum wage causes unemployment. And to answer that question, we don’t need to rely on picking apart the methodology of one paper — we have a whole ton of papers. Unemployment at the city level is very easy to observe in the data, and a ton of people study it. Back in early 2021 I wrote a pair of posts about the academic literature on this question, and I don’t think there have been any big revelations since then:

The basic conclusion from the (very big) academic literature is that minimum wage hikes, at least to the levels that we usually discuss in the U.S., are usually pretty safe — but not always. There are some low-productivity cities where forcing a Seattle-level wage will actually throw some people out of work.

The thing is, these cities are highly likely to be in the middle of nowhere — e.g. rural Kansas — rather than big rich expensive cities on the coast. So the recent paper by Hill (2023) that Megan McArdle cites is a bit suspicious, because it’s claiming big unemployment effects in the precise places where we would think — and where a vast existing literature says — that they’re least likely to appear.

Looking at the paper, it’s easy to see where a mistake could have been made. Hill looks at cities that raised their minimum wage. But these cities tended to be places that were experiencing a rise in costs from an inflow of knowledge industries and high earners — like San Francisco or Seattle. That same inflow both A) makes it easier to pay high wages, making minimum wage less likely to hurt employment, and B) raises rents a lot, pushing a bunch of people out of their homes onto the street.

In other words, this looks like a case where the assumption of causality is suspect — the policy changes being studied aren’t exogenous to the outcome measure being examined. What you want to do in a case like this is to use synthetic controls to control for the characteristics of the cities themselves, so that you control for things like inflows of high-earning workers.

So I wouldn’t worry too much about this paper, or let it change your general opinions about minimum wage.

@Noah, my steelman case for socialism is basically Fully Automated Luxury Communism.

I think that if Marx were alive and read-in on the last 150 years of history, he would declare that Western and Northern Europe’s social democracies were the closest to his vision of the “dictatorship of the proletariat”, because all he had really meant by that infamous phrase was that true democracy would enable the proletariat to dictate terms to capital.

Which is exactly what happened in postwar Europe! Labor slowly chipped away at capital’s power, bargaining its way into now-entrenched social welfare states.

Marx would also declare that the Russian communists had completely lost the script, and that’s why they utterly failed despite giving it a valiant college try.

It’s a common sport to stand-up Sanders as a one-dimensional cardboard cutout. I understand that impulse, but let’s look at few things seldom mentioned when Sanders is used in a political/economic discussion. Biden made a very important pivot in the month of July leading into the 2020 election:

https://www.vox.com/platform/amp/21317850/joe-biden-bernie-sanders-task-forces-progressive-agenda

Sanders is one of the few Senators who saw and voted against W’s Big Lie in re aluminum tubes and white cake — worst foreign policy decision in decades.

Sanders does something no other losing presidential candidate does: works his ass off in multiple rallies and fund-raisers for the candidates who beat him: he did 43 appearance/fund-raisers for Obama, whereas Hillary did 13 closed-door fund-raisers. When late in the run-up to the Democratic Party Convention, Ted Kennedy told Bill Clinton he planned to endorse Obama, who could forget Bill Clinton’s response: “Fifteen years ago, this guy would have been carrying our bags!” Lovely people, The Clintons.

The $15.00 minimum wage is an interesting point. Which candidate in a Democratic Presidential Debate forced Hillary to say she supported a $15.00 minimum wage? Sanders.

When Biden won the Democratic Party Nomination, no other defeated candidate worked harder than Sanders, who attended multiple rallies and fund-raisers.

The back-bench mitten-wearing photo of Sanders sitting alone at Biden’s Inauguration made for a nice internet meme. Biden made clear his view of Sanders, when, at the conclusion of his first State of the Union Address, he made a beeline for Bernie and embraced him in a bear hug. Sanders just happened to have a better seat, down front, on the aisle.

Losing candidates such as Sanders, like it or not, have a positive role to play in elections with razor-thin margins. Stacey Abrams couldn’t win public office in Georgia, but, boy, did she deliver an unexpected one-tie-breaker-vote Senate, using her organization to turn-out the vote.

Both Sanders and Abrams have spent years building organizations that stand the test of time, not the typical ad hoc, this-election-cycle ephemeral entities of many candidates. Like it or not, these organizations are critical. Without that one-tie-breaker-vote Senate, the IRA would be but a pipe dream.