Americans are generally richer than Europeans

But being rich isn't the only thing that matters

Around the 4th of July, there’s always a big Twitter fight between Americans and Europeans online over which place has higher living standards. In terms of good old per capita GDP, it’s not much of a contest:

Switzerland has higher per capita income than the U.S., but the U.S. comes out ahead of the Northern European countries — Sweden, Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands — and well ahead of other European countries like France. (The EU itself is even lower because it includes East Europe.) In fact, in per capita GDP terms, the state of Arkansas — the second-poorest U.S. state — is actually about as rich as the United Kingdom, and Georgia — the median U.S. state — is richer than Denmark.

But as many people on Twitter will be quick to tell you, per capita GDP isn’t the be-all and end-all measure of living standards. After all, isn’t Europe far more economically equal? Doesn’t the government provide a lot of things for free that Americans have to pay for out of pocket? Isn’t the health care better? Don’t Europeans get much more vacation? And on top of all that, many people who travel to Europe, or who have lived in both places, insist that life in Europe just feels nicer.

Well, it turns out that both the America boosters and the Europe partisans have good points. By almost any economic statistic we can find, Americans tend to enjoy higher material standards of living than their European counterparts. But when it comes to quality-of-life measures that aren’t included in GDP, Europe tends to come out ahead.

Some issues to think about when comparing living standards

When we go looking for economic numbers to compare living standards across different countries, there’s lots of stuff we have to take into account. Here are a few of the important considerations.

1. Purchasing power parity

Living standards aren’t just about how much money you get; they’re about how much stuff your money can buy. The same goods and services cost different amounts in different countries. The main way economists try to account for these local price differences is called Purchasing Power Parity, or PPP. There are lots of shortcomings of this approach — for example, it assumes that the quality of lots of stuff is constant across different countries, so that a haircut in Japan is the same as a haircut in the U.S. (I can assure you that the former is better). But in general, adjusting for PPP is better than not adjusting for it. Note that the per capita GDP numbers in the graph above are already adjusted for PPP, since they’re in “international dollars”. In fact, most of the numbers I’ll show will be PPP-adjusted.

2. Means vs. medians

Remember that per capita GDP is an average number — you just take the total income of the country and divide by the number of people. But this means that a few outliers can really distort the numbers; remember, when Michael Bloomberg walks into a bar, the average income of the bar immediately goes up to millions of dollars. But the typical person in the bar doesn’t earn any more than before. So when we want to compare how the typical middle-class person lives in different countries, we should use a median instead of a mean. Unfortunately, we don’t always have data on medians, since this requires doing surveys, which is harder than simply collecting the aggregate data that’s used to calculate means. (Note: If you’re dealing with median household income, you should also adjust the median numbers to take household size differences across countries into account.)

3. Inequality/poverty

Median income will tell you the living standard of a typical or middle-class person, in the middle of the income distribution. But if one country leaves a large segment of its populace to languish in poverty and another doesn’t, that matters in terms of overall living standards. We can use a Gini coefficient to get an estimate of inequality, but I prefer the relative poverty rate. And the best measure of all, when it’s available, is the income of the typical poor person.

4. Disposable income

Government-provided services like education and employer-provided benefits like U.S. health insurance premiums are definitely counted in GDP — just because people don’t pay for something out of pocket doesn’t mean it magically gets dropped from the statistics. But people may not place an equal value on a dollar of stuff the government or their employer gives them and a dollar of stuff they buy for themselves. And the value of a dollar of in-kind services might differ between countries in ways that PPP just can’t catch — for example, the U.S. spends much more per capita on health care than European countries, but achieves roughly the same outcomes overall. So in addition to income numbers, it’s often helpful to look at take-home income, also called disposable income. Or if you do think government services are worth the amount they cost, there’s a number called “adjusted disposable income” that adds in the value of government services received.

5. Consumption

In the final estimation, what really matters for material standards of living is not how much people earn but how much they consume — including what the government gives them to consume, such as free education. (In fact, there are some economists who think investment shouldn’t even be counted in GDP!) Of course, consumption is only a snapshot in time — if a certain country’s people over-consume and don’t invest enough, their consumption will stagnate or fall in the future. But consumption can be another helpful number to look at.

6. Work hours

People in different countries work different amounts. Most people value their leisure time, but leisure isn’t counted in GDP. So we should also look at leisure time when comparing living standards.

Anyway, these are just a few issues to think about as we try to compare America to Europe.

Why America is generally richer than Europe

First let’s look at median income. The U.S. is famously more unequal than Europe, so we’d expect this to be a closer comparison than GDP. But in fact we find that the U.S. does considerably better than most European countries, and almost as well as Switzerland:

In fact, the median income gap between the U.S. and Denmark, adjusted for PPP, is greater in percentage terms than the per capita GDP gap! (Though there was almost a convergence during the Great Recession, after which the U.S. bounced back strongly.)

What about disposable income? Here, the U.S. also comes out ahead, beating even Switzerland:

What about adjusted disposable income — adding government services back in? Here, sadly, we don’t have median data, so we can only compare means. The U.S. comes out comfortably ahead:

Now, although this is just a mean instead of a median, it seems unlikely that a few rich Michael Bloomberg types are dragging up the U.S. average a lot more on adjusted disposable income than on non-adjusted disposable income. Remember that the difference between those is just the value of government services, and it’s unlikely that there are a few people hogging tremendous amounts of government services. So really, the U.S. just comes out ahead here again.

Finally, what about consumption? Here we again don’t have medians, but since rich people tend to save most of their income instead of consuming it, the mean is probably a lot less skewed here than for income. Via Ireland’s Central Statistics Office, here’s an international comparison of a measure called Actual Individual Consumption, which includes both personal and government consumption:

Once again, the U.S. comes out significantly ahead of Europe. Now, the U.S. does have a lower national savings rate than most European countries, so we may just be overconsuming to some extent, but again this is just one more data point showing that the typical American enjoys a higher material standard of living than the typical European.

But now note that not all people are typical. When it comes to the people at the bottom of the distribution, the U.S. does less of a good job. Here’s a chart showing the cutoff of the poorest decile of disposable income — i.e., how much cash you take home each year if you’re at the top of the poorest 10%.

A person at the cutoff of the bottom 10% in the U.S. takes home only $11,287 per year, while their counterpart in Denmark takes home $15,607.

And in fact the gap is even greater, because the U.S. is generally less redistributive than Europe. Here’s a chart of social welfare spending as a percent of GDP, which is a decent rough measure of how redistributive a country is:

So the American middle class is doing better in material terms than the typical European. But if you’re poor, it’s probably better to be poor in Europe.

Before we move on to non-material stuff, it’s worth it to ask why the U.S. is richer than Europe. One reason, as we’ll see, is that Americans work more. Another reason is that the U.S. has a large endowment of natural resources, while European countries often have to pay for these from overseas. There are also some indications that U.S. businesses are better at adopting new technologies than their European counterparts. The U.S. also traditionally has had higher productivity in service industries. So U.S. institutions may simply be geared toward making businesses more productive.

Why Europe generally feels nicer than America

So if the U.S. is richer than Europe, why does Europe feel like such a nice place to live? Well, one reason might be that in Europe, people work less.

This gap hasn’t always been there; it opened up in the 1980s and 1990s, when Europeans started working a lot fewer hours, and American hours held pretty much the same. (In case you’re wondering, U.S. productivity per hour worked is a tad less than Switzerland or Germany, a tad more than Denmark, France, and the Netherlands, and a lot more than Sweden or the UK.)

How much to work and get material stuff vs. how much to enjoy leisure is a choice — a personal choice, and also a social choice via laws that limit work hours. You can get more stuff, or you can enjoy an easier life. Like the hitchhiker in the movie Slacker says: “I may live badly, but at least I don’t have to work to do it.”

So the fact that Europeans don’t work as much as Americans in no way invalidates or reverses the fact that Americans have higher material standards of living. It just means there’s a tradeoff here. America chooses more stuff and less leisure; Europe chooses the opposite.

Leisure is far from the only difference in quality of life, though. Health and safety are also important.

It’s hard to get a good comprehensive measure of the health of a population, but life expectancy is probably a decent proxy. And though the U.S. has never really shone relative to Europe, in recent years it has begun to lag severely:

In terms of safety, the U.S. also lags pretty badly. Even before the massive homicide wave of 2020-22, the U.S. had far, far more murder than Europe:

And this is probably a decent proxy for assault and armed robbery as well. We also have a much higher death rate from cars:

I could go on, but the pattern is pretty clear. The U.S. in general is less healthy and less safe than Europe.

Health and safety aren’t counted in GDP. If people could move freely throughout the world, then health and safety would be counted in GDP, since rents would rise in healthier and safer areas when people flooded into those areas (and rent is counted in GDP). But in fact, people can’t easily move from the U.S. to Europe or vice versa, given immigration laws and language barriers. So Europe’s greater health and safety, along with its greater leisure time, represent a real quality of life advantage over the U.S. Income and consumption aren’t the only things that matter.

So in many ways, Europe is just a nicer place to live than America, even though in America you get more stuff (unless you’re poor).

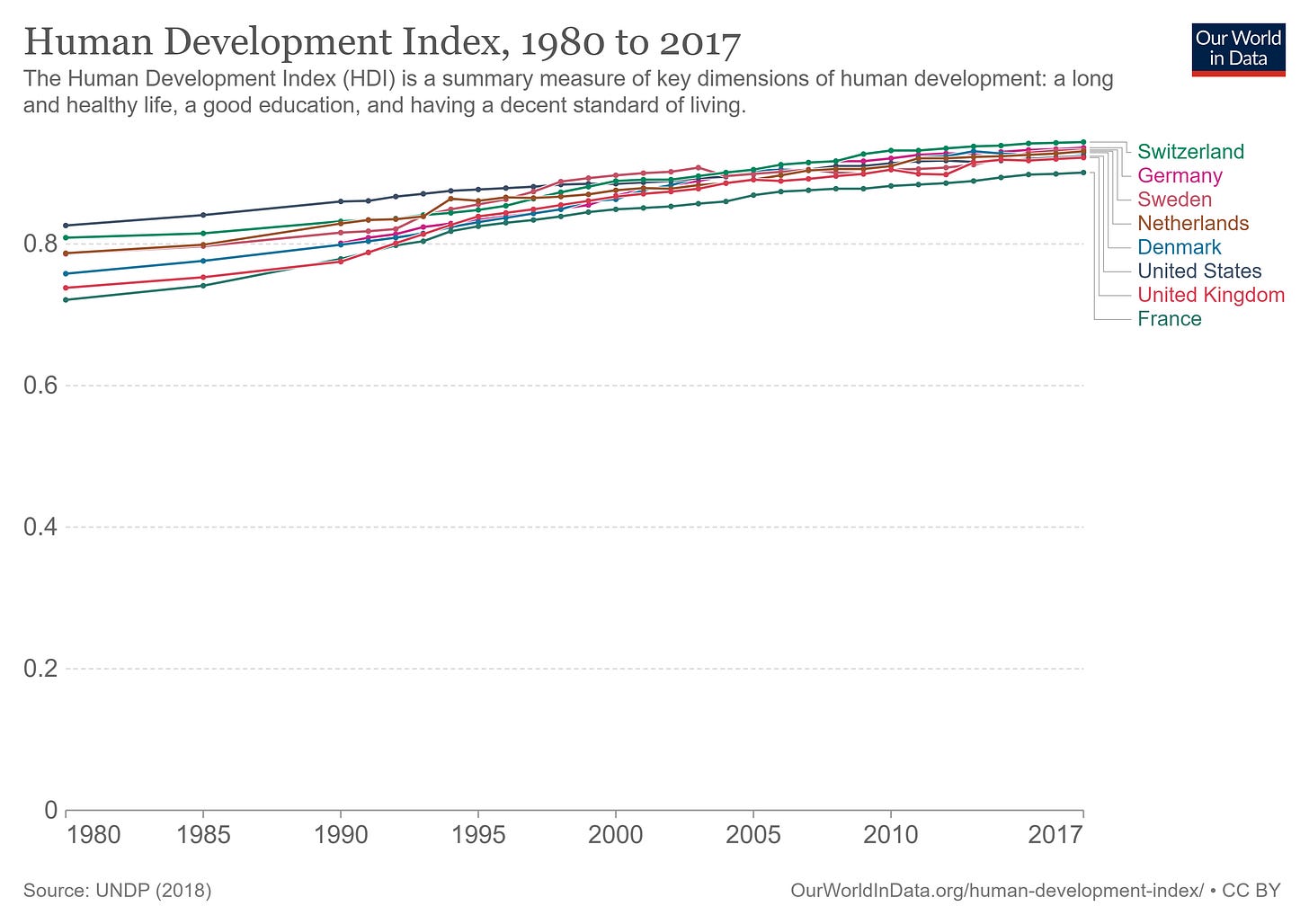

But as one final thought, I’d like to offer the hypothesis that life is just about equally as good in all developed countries. There’s personal preference, of course — if you want a big house and a lawn, you might prefer America or Canada, whereas if you want national health insurance and lower crime rates, you might prefer Japan or France. But in terms of where the average person would want to live given the choice, I think all these rich countries are in the same ballpark. This is certainly true when we look at the Human Development Index, which combines income, health, and education:

(Update: Also, some economists who tried to compare overall economic + non-economic welfare across countries found that the U.S., the UK, and France were all pretty similar.)

When it comes to comparing America to Europe, or to other rich countries, the similarities are a lot more important than the differences.

Yeah, I'm an American who naturalized in Spain. Like it just seems completely outside of debate that Americans are way richer overall. Like the idea of a regular middle class family having a 2000 square foot detached house with a yard and two cars is just bonkers in Spain.

Yet I choose to live in Spain because I value the lifestyle and social connections.

Now onto two points.

First as someone who has done a lot of work on both continents the one thing Europe can really learn from America is to let jobs die. The Nordic system tends to do a pretty good job of this with the whole "protect the worker, not the job" philosophy, and it's no coincidence that most European tech start-ups are from there. The government accepts they don't have a role in the private allocation of labor and that the large social spending is taken from the riches created by a dynamic market. In Southern Europe, we'd still have blacksmith guilds if lots of people had their way and the protectionism is crazy. EU is helping a bit by forcing cartels to have to open up. But just as an example, when I moved to Spain it was cheaper to get a container into Southampton, UK and truck it to Madrid than to unload in Spain because of the insane costs of Spanish ports.

Now for the part with people's wealth, in Europe intergenerational wealth is so much more important than in the US. Especially now with declining birth rates so much more of people's overall wealth is inherited. These tend to be modest but it also makes mobility harder. I have major problem with how mobility is measured since most people at some point in their life will move through the quintiles of income both up and down. I can say it just seems patently obvious that the idea of being able to get a decent amount of wealth with not a lot of education is absurdly easier in the US. The adage I usually say is that "It's better to be poor in Europe and it's better to be rich in Europe, but it's so much easier to go from poor to rich in the US"

I think this is exactly right. One thing I wonder is, how much of American wealth goes into the much stronger preference for large houses? Not only are they expensive in and of themselves, but the costs around them – having a car, maintaining access to suburbs, maintenance, time spent commuting – seem really high, and I wonder if it would account for a large chunk of the perceived quality of life gap.

I have a little pet theory about this, since it's not like larger apartments and mansions aren't status symbols in Europe. In most places, though, the prestige of a large home and the prestige of a _central_ home cancel each other out; if you're a billionaire you can have both but for most people it has to cancel out somehow. But America – due to some combination of white flight, endless land, and being rich enough for mass car ownership, etc. – completely lost the centralising force outside of a few urban areas, so 'larger even if further' became a widespead norm outside of a few metro areas. And somewhere like Manhattan, where millionaires are happy with well-located 2-bedrooms, not coincidentally feels more livable.