The pushback against industrial policy has begun

So far, it's a vague broadside instead of a targeted criticism.

Note: This post originally misattributed an Economist article by Christian Odendahl to Mike Bird. The Economist does not publish bylines, and I had accidentally received the impression from a Twitter discussion that Bird had written it!

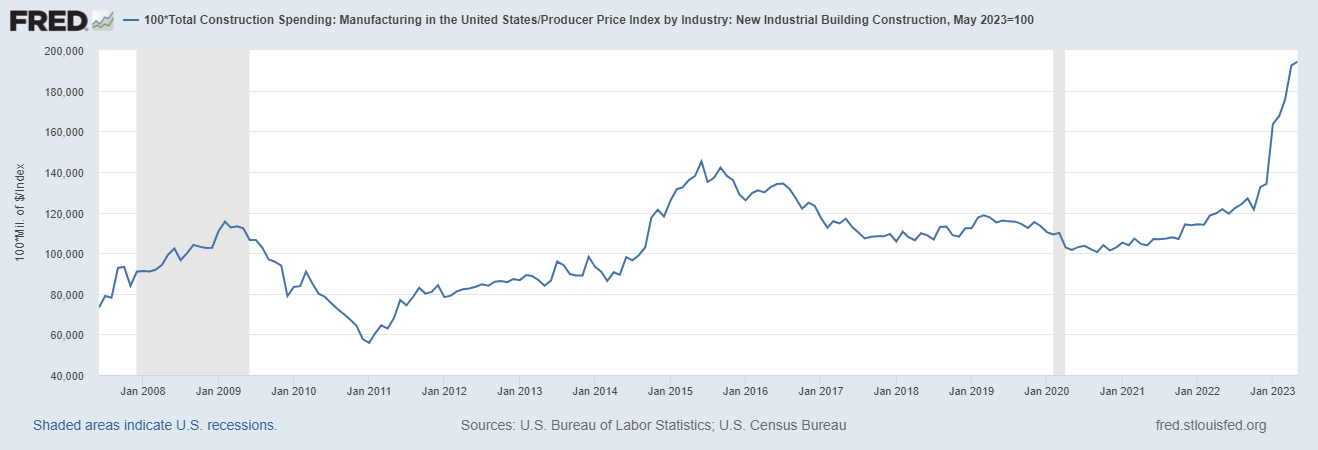

In the 2020s, America has begun to change our economic policy paradigm — the basic framework that leaders and intellectuals use to decide whether a policy is good. The old “neoliberal” consensus, which had already taken body blows from the disaster of 2008, the coming of climate change, and the collapse of the manufacturing workforce in the 2000s, was decisively slain by the dual realization that “free trade” had enabled the rise of the most economically formidable great-power rival the U.S. has ever faced. The new framework could roughly be called “industrial policy”, and its first big implementation came in the form of the CHIPS Act and the Inflation Reduction Act. Those two laws have resulted in a massive factory construction boom:

If you’d like to track where these investments are going and what they’re building and which laws enabled them, Jack Conness has made a cool dashboard.

It was inevitable that this big shift would generate lots of pushback. In fact, that’s a good thing. We don’t really know what “industrial policy” means yet; beyond the specific examples of boosting semiconductors and green energy, we don’t have a general framework to think about which industries to support, or where, or how. As Greg Ip points out, we also don’t have much economic research on the subject — even the few papers that exist are mostly about growth policy in developing countries. Nor do we know whether Biden and progressives have come up with the best formulation of industrial policy; perhaps conservatives can come up with their own rival vision for how to make it work. The more critics push the industrialists, the more they (or maybe I should say “we”?) will be forced to think about and answer these questions instead of stumbling blindly forward.

The initial criticisms I’m seeing, however, are mostly just broadsides against the whole idea of industrial policy. For example, the Cato Institute came out with a pair of reports in 2021 lambasting industrial policy before we even knew what Biden was actually going to do. You expect Cato to write stuff like that. They are libertarian ideologues, and they function as a “loyal opposition” who can be expected to dismiss the new paradigm out of hand — we still need to grapple with their arguments, but we don’t expect them to be fair and balanced.

But just the other day, Christian Odendahl of The Economist came out with a long piece entitled “The world is in the grip of a manufacturing delusion”, whose subtitle was “How to waste trillions of dollars”. The piece really fails to come to grips with most of the reasons that industrial policy is being rolled out, and when it does address some of them, its criticisms are generally misguided and overly dismissive. I don’t necessarily blame Christian or The Economist for this; instead, I think it means that supporters of industrial policy need to do a better job communicating the basic raison d’etre of the whole idea. Better communication on our part will enable the critics to do better as well.

So without going into the questions of whether industrial policy will work or exactly how it should work — which will take decades of thought and discussion and research, and which I will of course write much more about — I’d like to clarify what I see as the goals of industrial policy.

Industrial policy isn’t really about good jobs in factories

The sales pitch for any economic policy in America is always “jobs”. Tax cuts were supposed to work by incentivizing “job creators”. Trump’s tax cut in 2017 was called the “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act”. Bush’s 2003 tax cut was called the “Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act”, and so on. Every American President and politician promises that their policies will create jobs, jobs, jobs. Biden is no different — he sells the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS Act by talking about how many jobs they’ll supposedly create.

I’m not happy about the fact that America thinks of economic policy in terms of number of jobs created. It’s not a very clear or meaningful way to think about policy — overall employment is more a function of macroeconomics than micro, so we should really be talking about the results of policy in terms of wages and incomes. But “jobs jobs jobs” is how the game is played, and so we should just expect any politician to talk about that a lot, without assuming that “job creation” is the true underlying economic rationale for any policy.

So far, the critics of industrial policy tend to spend a lot of their time rebutting the notion that we can bring back the golden age of widespread “good jobs” in factories. For example, Odendahl writes:

[P]oliticians in the West say that factories are a source of solid jobs that produce a bigger and more satisfied middle class…The notion of a “good manufacturing job” is an old one…

It is far from clear such jobs can be brought back—no matter how much governments spend. For a start, the manufacturing wage premium has fallen sharply. Production workers’ wages in America now lag behind those of similar service-sector workers by 5%. Moreover, the sort of high-tech factories that America and Europe are attempting to attract are highly automated, meaning they are no longer a significant source of employment for people with few qualifications.

The Cato reports spend much of their time making this same point at much greater length.

And they’re right. Industrial policy will not turn us back into a nation of factory workers. Every country in the world, including China, sees its share of manufacturing employment fall as it becomes rich — both because consumers start demanding more services as they get richer, and because rich countries can only stay competitive in manufacturing by using lots of automation.

If we do manage to engineer a manufacturing boom, most of the actual production work will be done by robots, because we are a rich country with very high labor costs and lots of abundant capital and technology. Automated manufacturing is what we specialize in, not labor-intensive manufacturing. The latter is for countries like India and Tanzania. America needs to build with robots.

Now, that doesn’t mean industrial policy won’t create any jobs for lower-skilled workers. The factory construction boom will employ a lot of construction workers. Building solar plants and wind farms takes a lot of semi-skilled labor. Semiconductor fabs need janitors and security guards and cooks and so on. But that isn’t really the point of the policy. Nor is the point to create work for the higher-skilled workers who will design and operate the robotic factories of the future, or who will provide manufacturing-related services.

It is possible that industrial policy will have overall benefits in terms of increasing labor demand and raising wages and incomes, through mechanisms other than direct “job creation”. I’ll talk about that in a bit. But the main purposes of industrial policy — or at least, what I believe should be the main purposes, and what I think actually did motivate the big shift we’ve seen over the last few years — really have nothing to do with bringing back the workforce of the 1950s.

Decarbonization

The first main purpose of industrial policy is decarbonization. Climate change is a major threat, even an existential threat, to our way of life. And we have only two options for stopping it: the mass global impoverishment of degrowth, or building a bunch of green energy to replace fossil fuel energy. That’s it. Those are our only two options. And mass global impoverishment is dumb, so let’s do the second one.

Decarbonizing the U.S. economy will require an absolutely massive amount of industrial output. Much of that output will have to be domestic. Even if we don’t build all the solar panels ourselves, we must do the work of installing them. We must rapidly replace most of our vehicle fleet with electric vehicles; because cars and car batteries are very heavy, we are unlikely to do most of this by importing cars from China (though I suppose the Europeans are trying).

The basic economics of an environmental externality should be well-understood by everyone now; the free market won’t eliminate climate change on its own, so government needs to put its thumb on the scale. Of course you can wave your hand and say that in theory, we could do this with carbon taxes instead, but carbon taxes are very politically difficult, and policy is the art of the possible.

There’s also another important reason why subsidizing green energy is better than a carbon tax, and that’s learning curves. The more of stuff like solar and batteries we build, the cheaper it gets:

Of course that’s just a correlation, but there are good empirical and theoretical reasons to think that there really is a causal effect here; if you build more green energy, the price of green energy goes down. So far, forecasts of green energy adoption using learning curves have held up even in the presence of large-scale subsidies, suggesting that the policy works. And research on the causes of the incredible drops in solar costs points to scaling effects as the biggest factor in recent years.

Carbon taxes, even were they politically feasible, accomplish some decarbonization via incentivization of green energy scaling, and some via degrowth. The technological externality of scaling — which, by the way, is global, not just localized in the U.S. — means that we want to do more via the former and less via the latter. Thus, industrial policy like the IRA should be our go-to policy for fighting climate change.

Odendahl argues that green energy will take over anyway, simply due to demand:

Another case for spending state cash on industry—particularly the green kind—is that the world will soon need more physical goods if it is to reach net-zero emissions…[But money shouldn’t be spent on] green equipment, where demand will create supply. Solar panels show how the process will probably play out. The current boom in demand—America installed 47% more in the first quarter of 2023 than in the same quarter last year—has prompted companies in China and elsewhere to boost capacity. The Energy Transitions Commission reckons that existing production of solar panels already exceeds probable demand until 2030, which is also the case for batteries when planned production is included (see chart 4). In other areas, like heat pumps, capacity can be added quickly if desired.

This is true in the long run — the cost of renewables has fallen to the point where they’re simply a superior technology — but it completely ignores the question of time. Researchers agree that the IRA will significantly accelerate the timeline of U.S. decarbonization:

With climate change, every additional ton of carbon pumped into the atmosphere counts. So time is of the essence; we could just wait for natural demand to replace fossil fuels, but we shouldn’t. Critics of industrial policy need to acknowledge that.

Now, this obviously doesn’t mean everything the Biden administration is doing on this front is correct. Maybe instead of incentivizing domestic solar production, we should be buying our panels from China, and simply incentivize domestic installation only. but at that point we’re arguing about specifics; I simply want to point out here that rapid decarbonization is a legitimate goal of industrial policy, and that critics need to either acknowledge that or come up with better counterarguments.

National security: high-tech weaponry

The IRA is about decarbonization, but the CHIPS Act is about something very different: national security.

If you’ve been following the Ukraine War (or if you read Chip War), then the importance of precision weaponry can’t have been lost on you. As this excellent report in The Economist details, the ability to hit targets precisely — with drones, GMLRS rockets, anti-ship missiles, Excalibur shells, and so on — has been a game-changer on the battlefield. What all of these precision weapons share is that they use computer chips to guide them to their targets. In other words, in order to produce a whole bunch of really good weapons, you need to produce a whole bunch of computer chips.

Suppose China made most of the world’s computer chips, and suppose a war broke out between the U.S. and China over Taiwan, or the South China Sea, etc. Do you think China would simply continue to sell us large volumes of the computer chips we needed in order to make the weapons necessary to win that war? No, it would not. So preserving the ability to make computer chips outside of China is critical to our national security. Some of that production can and will take place in friendly countries like Japan and Korea. But China may be able to interdict shipping from those places in the event of a war, so it makes sense to keep some production in the U.S.

Even more crucially, as Chris Miller explained in our recent interview, being able to produce leading-edge chips is very important for preserving our military edge of China. We can produce some of these in friendly countries, but again, they might get interdicted in a war, and also producing them here means we don’t have to worry about political risk at all.

National security is a public good — it’s not the kind of thing we can rely on the free market to provide on its own. When an American chip company decides to shut down in the face of Chinese competition, its decision is not taking into account the implications for weakened U.S. national defense; it is thinking only of dollars and cents. Thus, government needs to put its thumb on the scale. So far I don’t see critics of industrial policy arguing against this notion, or even grappling with it.

National security: supply chains

There’s a second sort of national security issue involved in industrial policy: supply chain robustness, also sometimes called “supply chain resilience”. In the early days of the pandemic, the U.S. was notoriously unable to manufacture enough Covid tests, masks, or ventilators, and the result was unnecessary death. This experience showed that a lack of production capacity for simple, low-margin goods can make economic sense in good times but go catastrophically wrong in bad times.

In the language of economics, profit maximization happens on the margin, but disasters are “inframarginal” — they represent such a big shift from normal that companies are effectively unable to incorporate disaster risk into their decision-making. The government thus needs to step in.

Odendahl argues that incentivizing domestic production will decrease resilience rather than increasing it:

[R]esearch published last year by the imf suggests that greater self-sufficiency is likely to leave countries more vulnerable to future shocks, rather than less. Reshoring would make production dependent on conditions at home, and vulnerable to a big local shock. By comparison, diversified supply chains are more resilient, since they depend on the economic performance of a range of different countries.

If you’re talking about a shift to full autarky — everyone making everything domestically — then of course this makes sense. And though I’m not sure what IMF paper the Economist is referring to, papers that I’ve seen them write on this topic do tend to assume a world of autarky. But in reality, supply chain robustness (or resilience, or whatever) isn’t about autarky; it’s about diversification.

If we import 100% of our batteries from China, then we’re subject to both global shocks (a pandemic or a war) AND China-specific country shocks (policy mistakes, political instability). But if we produce 50% in China and 50% in America, then either of those shocks will affect only 50% of our production rather than 100%. We’ve taken on some additional America-specific country risk, of course, but if this is mostly uncorrelated with global and China-specific shocks, then we’ve diversified our portfolio. The effects of this sort of diversification are an externality at the firm (company) level; an American company that moves production to China doesn’t experience the full impact of the increase in aggregate risk that this might entail if all the other companies are also producing in China. So this is a reason for government to step in and motivate some international diversification.

There’s also the question of optionality. If we concentrate our production of anything in China, then China’s government can simply threaten to cut off our supplies of that thing in a war situation. Odendahl’s article largely waves this danger away:

China has provided another nudge in this direction. On July 3rd the country announced plans to restrict the export of two metals, gallium and germanium…[but h]ow disruptive are supply restrictions in reality? In the case of some rare “war metals”, perhaps very. But market economies can adapt to painful limitations. When Russia launched its war in Ukraine last year, continental Europe received 40% of its gas from the invading country…[but European] governments secured supplies elsewhere; firms invested in gas-saving equipment, or found different energy sources; households consumed less. European gas consumption in the seven months to March was almost a fifth lower than in previous years. The economy weakened, but a crash was avoided. It was a similar story when China cut the supply of rare earths to Japan in 2010. Companies found ways to replace these inputs without disrupting production too much. Markets have a natural capacity to overcome shortages, for the simple reason that firms seek to make money.

But these examples may not apply in a U.S.-China war. First of all, energy is a pretty fungible good — there are lots of ways and lots of places to produce it, which is why Europe was quick to substitute liquefied natural gas and energy alternatives for the lost Russian gas. If China maintains strategic choke points over highly specialized manufactured goods, those may not be as quickly substitutable in a crisis.

More worryingly, a U.S.-China war might be more akin to the early Covid pandemic than to the Ukraine war. Covid was a global shock, and the U.S. was unable to secure enough masks or Covid tests because we didn’t know how to make them at scale and we couldn’t import them from anywhere. In the Ukraine war, the U.S. Navy still rules the seas, so Europe could still import energy from abroad; in a U.S.-China war, the seas will be contested, so we may not be able to import stuff as easily from abroad.

Anyone who doubts the ability of wartime embargoes and blockades to affect countries’ production capacity should go look at what the Allies did to the Axis in WW2. Those dangers can’t be waved away with “firms seek to make money”, because Axis firms also sought to make money; they just couldn’t, because the U.S. had the option to cut them off from many crucial war production inputs.

Now again, this is not an argument for autarky. It’s an argument for diversification, so that in the event of a big war, there’s no critical component that we have to learn how to make from scratch.

Economic justifications: Clustering, multiplier effects, and export productivity

So the main reasons for industrial policy — not just my own theoretical reasons, but the actual reasons that the Biden administration pushed the IRA and the CHIPS Act — have nothing to do with “good factory jobs”. They’re about external threats — climate change and the military threat from China. Any case against industrial policy has to deal with those arguments first and foremost.

But that said, there are also some potential economic justifications for industrial policy. I’m not strongly asserting that these are correct; simply mentioning that the arguments exist and need to be investigated and addressed.

The first of these is the idea of clustering. This is the tendency of high-value knowledge industries to locate in clusters, like information technology in Silicon Valley, finance in New York City, and entertainment in Los Angeles. A bunch of economists have studied the effect of clusters on innovation, and generally agree that it’s pretty significant. China has one of the world’s top electronics manufacturing clusters; the U.S. no longer does. Perhaps industrial policy could help create an advanced electronics manufacturing cluster in the U.S.; it’s a question at least worth thinking about.

Now, you can argue that the U.S. already has clusters in software, finance, entertainment, and other industries, so why do we need another in high-tech electronics manufacturing? Well, Ricardo Hausmann and his co-authors argue that a nation’s growth potential depends on its economic complexity — that instead of simply specializing in one thing it does really well, a nation should be able to do a whole lot of different stuff. (This fits with Paul Krugman’s “new trade theory” more than with David Ricardo’s more classic version that was based only on specialization.) So perhaps America is missing out on some opportunities for wealth generation by not having much of an electronics cluster.

Advanced manufacturing can also create labor demand and increased economic activity in other industries. When you make products locally and sell them elsewhere, the export revenue gets spent locally, on everything from houses to doctor’s appointments to haircuts and pizza. This boosts local economic activity, raising labor demand (i.e. “creating jobs”), boosting wages, and so on. It’s called a local multiplier effect. Moretti (2010) attempts to quantify these effects for advanced manufacturing, and finds that they’re substantial:

I quantify the long-term change in the number of jobs in a city’s tradable and nontradable sectors generated by an exogenous increase in the number of jobs in the tradable sector…I find that for each additional job in manufacturing in a given city, 1.6 jobs are created in the nontradable sector in the same city. As the number of workers and the equilibrium wage increase in a city, the demand for local goods and services increases. This effect is significantly larger for skilled jobs, because they command higher earnings. Adding one additional skilled job in the tradable sector generates 2.5 jobs in local goods and services.

Moretti cautions that the benefits of these multipliers may not exceed the costs of subsidizing export industries. But they might! In any case, it deserves investigation and thought.

More broadly, we need to recognize that just because most Americans work in the service industry these days doesn’t mean that subsidizing manufacturing won’t create jobs. Manufactured products are easy to export, so local manufacturing tends to create service-sector jobs in the local economy. The argument that “well, most people in rich countries work in services, therefore manufacturing won’t create jobs” just doesn’t take local multipliers into account.

(And remember, by “create jobs” I really mean “raise labor demand”. Sigh.)

Finally, there’s the idea that subsidizing exports boosts productivity. This is the core of the argument of industrialists like Ha-Joon Chang and Joe Studwell. But if it works for developing countries, it might work for rich ones too. The basic theory is that left to their own devices, most companies will choose to stay in their safe familiar home market, selling to people nearby — but if the government pushes them to export, then they’ll get a productivity boost from having to compete in the rough-and-tumble global market. And remember that subsidizing exports means that net subsidies will go to manufacturing industries, since goods are generally easier to trade than services.

There are a few studies that seem to support this theory, but it’s still pretty unconfirmed. Yet it’s worth thinking about. Importantly, export subsidies are not a beggar-thy-neighbor policy — the U.S. can sell more cars to Japan, and Japan can sell more to the U.S., without either one incurring a trade deficit or seeing its domestic car industry fail.

So anyway, there are lots of potential economic justifications for industrial policy that the critics are mostly ignoring in favor of rebutting the “good factory jobs” argument. These justifications shouldn’t be treated as fact; the burden of proof is on advocates here, not critics, and economists need to do more research into each one of these. But critics of industrial policy shouldn’t be so quick to dismiss its potential economic benefits with a wave of the hand, either. I have seen nothing so far to make a reasonable person conclude with any conviction that U.S. industrial policy will be a “waste” of “trillions of dollars”.

My overall message here is that industrial policy for developed countries is an idea that’s still in its infancy. It’s being invented on the fly, in an ad-hoc manner, which seems necessary given the exigencies of climate change and deteriorating U.S.-China relations, but which also incurs obvious dangers. The imperatives of decarbonization and national security mean that the push for industrial policy can’t and won’t be simply waved away, so this is not a fruitful way for critics to spend their time. Economists and other intellectuals need to be thinking hard about all aspects of this idea, because the dismissals that worked in 2013 won’t work in 2023. America’s economic policy paradigm is shifting, and our thinking must shift to deal with it.

Updates:

Here’s another broadside against industrial policy, this time from Adam Posen of the Peterson Institute. He uses North Korea as a cautionary tale (!), indicating that he assumes industrial policy means cutting off all trade and reverting to North Korea-like autarky (which it does not). He also (mistakenly) thinks that the purpose of the Inflation Reduction Act was industrial competition, rather than decarbonization.

Meanwhile, development economist Reka Juhasz strongly takes issue with Odendahl’s assertion that her field has reached a consensus on industrial policy:

Nathan Lane, another researcher in the area, agrees.

I am willing to bet that in 2030 you will regret your enthusiasm for industrial policy. Call this a vague broadside, but I don't think that our government is capable of running this type of program in a way that ends up achieving (or even working toward) its goals and not becoming utterly corrupt. How are those ethanol mandates workin' out for ya?

Very helpful post in distinguishing the goals of industrial policy from manufacturing jobs creation.

One of the reasons that industrial policy and jobs creation are twinned together is local/state governments competing for these new businesses and factories. The smaller the unit of government, the less credible is touting the twin goals of climate and defense.

Just like the US can only do so much alone in fighting climate compared to a global view.