At least five interesting things to start your week (#3)

Japan's electronics boom; patriotism and economic policy; the disappointment of VR; the UK stagnation; macroeconomics goes micro

I’m still getting the hang of these roundups, but I think they’re going pretty well! Remember, if you’re a paid subscriber, and if you see interesting papers or news stories or anything else that you want me to blog about, drop them in the comments, and I’ll write something the following week if I think I have anything interesting to say.

1. Japan is back!! …maybe.

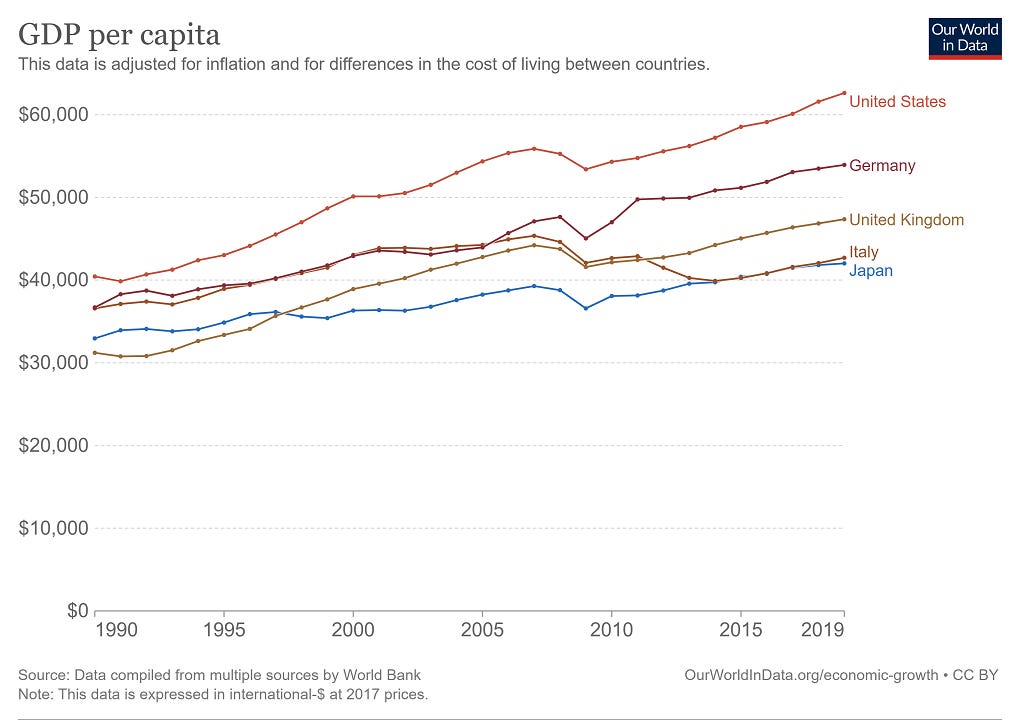

It’s now fairly common knowledge that Japan has fallen off economically. Its living standards now look more like Italy’s than like Germany’s:

Some piece of this is just population aging; Japan is the world’s oldest country, so there are fewer working age people to add to GDP. But Japan’s productivity performance has been truly atrocious, and aging probably only accounts for a small piece of that:

I wrote a series of posts about this last year, and there are probably multiple factors. But one factor that’s under-discussed is what economists call trade diversion. When Japan was at its relative economic peak in the 70s and 80s, it benefitted from having a unique niche in the global trading system — it could produce a vast array of high-tech, high-quality electronics at low cost, which few other countries could do. When South Korea and Taiwan learned to do the same, it created competition for Japan — think back to the Sony-Samsung wars — but when China began to do similar things at a truly massive scale, Japan lost much of its uniqueness in the global economy. (This was compounded by a corporate culture that was unable to pivot into new niches like software, and which maintained too much of a domestic-market focus.) When you get cut out of global supply chains, your measured productivity levels and GDP growth will take a hit.

If trade diversion is a problem, then Japan is in luck, because it could be a big beneficiary of the scramble to get electronics production out of China. In fact, since Taiwanese production would also be cut off in the event of a Chinese attack, and since South Korea is menaced by North Korea, Japan may be uniquely well-positioned to retake some of its old role as the center of the East Asian high-tech electronics cluster. And so it doesn’t surprise me that I’m seeing more stories like this:

CEOs are warming to Japan because it is the un-China.

It is a democracy, a U.S. ally and a safe place to share technology. Memory-chip maker Micron Technology just said it would put $3.6 billion into its Japanese plant, with Tokyo kicking in a chunk…

On Friday, the Nikkei Stock Average hit its highest level since 1990….

Japan’s politics may be dull, but for investors and CEOs, that beats the mercurial crackdowns led by China’s authoritarian leader or the game of chicken in the U.S. over whether to pay its debts…

IBM just said it would put $100 million into a partnership with the University of Tokyo and the University of Chicago to build a better quantum computer—a deal that would be impossible in China.

Don’t want to build your new fab in America, where construction costs are sky-high, skilled labor is scarce, and the lawsuit-driven permitting system takes years to navigate? Just build it in low-cost Japan, with its efficient bureaucratically-administered regulation and low-ish salaries! This logic is obviously compelling for companies like Taiwan’s TSMC and America’s Micron, both of which are now building fabs in the Land of the Rising Sun. Japan’s GDP growth in the first quarter was very robust, driven in part by high levels of private investment.

The weak yen should be a tailwind for these efforts. Despite the word “weak”, a cheap currency makes it very easy for foreign companies to invest in factories in your country, and to buy the products those factories produce.

Anyway, there are plenty of obstacles here — a shortage of skilled labor, the aforementioned ossified corporate culture, deficiencies in software, etc. — but for now, it’s enough to note that Japan has a huge opening here.

2. Some evidence on how to make people love their country

I’m a big advocate of leveraging patriotic sentiment, both to win political victories and to improve the provision of public goods. When people believe in their country, it can make them more willing to support policies that benefit the entire nation, rather than just their own small slice of the populace.

But anyway, that idea takes existing patriotic sentiment as a given. There’s also the question of how to actually increase that sentiment in the first place. Usually we emphasize cultural forces — politicians’ rhetoric, race relations, flags and symbology, etc. — in addition to external events like wars. But I also think there’s an economic dimension here — when people get economic assistance from the government, it can help convince them that the nation is on their side, and thus make them more patriotic.

As a demonstration of this, check out Caprettini and Voth (2022). The authors look at how much people benefitted more from New Deal spending in the years before WW2, and they found that people who benefitted from more spending tended to demonstrate more patriotic behavior later during the war. Importantly, they were more likely to join the military and to win decorations for their service. Here’s the paper’s abstract:

We demonstrate an important complementarity between patriotism and public good provision. After 1933, the New Deal led to an unprecedented expansion of the US federal government’s role. Those who benefited from social spending were markedly more patriotic during WWII: they bought more war bonds, volunteered more and, as soldiers, won more medals. This pattern was new — WW I volunteering did not show the same geography of patriotism. We match military service records with the 1940 census to show that this pattern holds at the individual level. Using geographical variation, we exploit two instruments to suggest that the effect is causal: droughts and congressional committee representation predict more New Deal agricultural support, as well as bond buying, volunteering, and medals.

The increase held in both rich and poor areas of the country, which is honestly pretty impressive. The paper doesn’t deal with the postwar G.I. Bill, but my bet is that this had something to do with the postwar upswing in patriotism.

This result implies two things. First of all, if they expect Americans to ask what they can do for their country, policymakers need to ask what they can do for Americans. We need to be thinking about how to craft policies that will convince the average American that their country stands solidly behind them.

Second, it implies that the relationship between patriotism and public goods provision is a two-way street — there can be a virtuous cycle where patriotic sentiment leads to more broadly beneficial government policies, which then make people more patriotic, etc. That’s a cycle we need to harness.

3. Why hasn’t VR succeeded yet?

I’m a self-declared techno-optimist, but I also like to think I’m reasonable and down-to-Earth about the fact that technologies often disappoint. Nuclear fission power, for example, is a technological marvel, but lack of scaling effects and an inability to overcome the public fear created by high-profile disasters have limited its impact on our society. And some high-profile things we call “technologies”, like crypto and the gig economy, clearly involve little new actual technological innovation and are mostly just regulatory arbitrage plays.

But one technology whose disappointment needs some more explaining is virtual reality. Since well before I moved out here in 2016, people in Silicon Valley have been very psyched about VR, but so far nobody really uses it for anything other than gaming. Facebook’s VR “Metaverse” cost tens of billions of dollars, but was a gigantic flop, and the company has pivoted away from the idea. Recently, the big story in the space is Apple’s new Vision Pro headset, but, tellingly, the new device is being pitched much more as augmented reality than virtual reality — a way of summoning a heads-up display of your computer screen, rather than a way of entering an alternate space.

What’s going on? There’s no shortage of real technological improvement in VR — my friend Sam D’Amico, who was an engineer at Oculus before leaving to run Impulse, would happily talk your ear off about how amazing the new products are. They’re light, breathable, incredibly high-resolution, and they track your face and body to provide an immersive, reactive experience. Nor is there a shortage of hypothetical use cases, as in crypto — VR could clearly be used for meetings, friend hangouts, events, virtual tourism, supply chain management, property viewings, social media, and much more. But the technological innovation doesn’t seem to be making most of the use cases happen, and that needs explanation.

Maybe the technology simply hasn’t reached some critical threshold of usability, but I think there’s something else going on here. We already have a technology that provides a very immersive audio-video experience much more cheaply than a VR headset, and it’s called a screen.

Human brains have a sort of magic property where they manage to feel fully immersed in a moving image on a 2-d screen. Peripheral vision is mostly imagination, so as long as your central vision is focused on the screen, your brain can imagine that the world inside the screen is actually all around you. This is why people have always been able to become totally engrossed in movies they watch on very small screens, from today’s smartphones to those tiny TVs your grandparents used to have in their kitchens:

In other words, the added value of a VR headset, in terms of audio-video immersiveness, is small. You can have Zoom meetings or virtual apartment tours on your phone and it works almost as well. Why pay $3500 for a fancy high-tech headset when you can get 90% of the value from a device you already own? VR is thus the opposite of Clay Christensen’s “disruptive innovation” — a high-end product trying to come into the market and shoulder aside cheaper, simpler solutions. That’s a very tall order.

Now, I do think that there’s one way VR could really change the world and fulfill its sci-fi promise, but it would be very difficult. If you somehow managed to add haptic feedback, you could create a virtual world that people could touch and feel instead of just see and hear. And that would do far more than any TV set or phone. In fact, if you look at sci-fi that involves VR, it pretty much always includes haptic elements. But right now, haptic technologies are still in the planning stages. If and when they become a reality, then I predict VR will conquer the world.

4. How recent is the UK’s stagnation?

A lot of people, including me, like to beat up on the UK economy these days. With its low investment in technological innovation, its excessive focus on finance, and its refusal to allow new housing construction, the UK is threatening to become the poster child for degrowth. While most countries have bounced back strongly from Covid, the UK remains mired in a grinding stagflation. A recent post by Joey Politano has some numbers:

Since the start of the pandemic, the US economy has grown by 5.4%, the European Union’s economy…has grown by 2.4%, and the UK’s economy has shrunk by 0.5%…[T]he UK arguably has the worst labor market recovery in the G7…[T]he British inflation crisis remains among the worst in the world…[The Bank of England forecasts that] the British economy will be a meager 1% bigger than pre-pandemic levels by 2025 and that there may well be fewer jobs than in 2019— making the first half of this decade a possible period of declining living standards in the UK.

And here is a graph:

No one reasonable will deny that the UK economy is in a parlous state at present. But there’s also a common narrative — which Politano echoes, and which I once subscribed to myself — that the UK’s stagnation dates back to the Great Recession. It’s common to post graphs of how UK productivity started growing more slowly after 2008, and to attribute this to policy mistakes.

But looking at the data on the years between the 2008 crisis and Covid, I’ve really begun to question this narrative. From 2008 to 2019, the UK’s GDP growth was very average for a rich country:

And although people love to point to the UK’s post-2008 productivity stagnation, in fact UK productivity growth in the crisis and post-crisis years kept pace with Germany and was faster than Canada, the Netherlands, or Japan:

Now, you can say that because the UK’s level of GDP and productivity is lower than the leading countries, they ought to grow faster. But that pattern of “convergence”, to the extent that it even exists, isn’t really about mature economies like the UK, Germany, U.S., etc. Once countries hit the technological frontier, there are often persistent gaps between their productivity levels that are very hard to explain. But in terms of growth, the UK seems to have done fine in the 2010s.

So I’m moving toward the opinion that the UK’s stagnation is a very recent thing — a result of Covid-era policy, Brexit, and the Russian gas cutoff.

5. Macroeconomics research is getting less theoretical

If there was one overarching theme of my original blog, it was the idea that macroeconomics needed to pay more attention to evidence and to stop accepting well-crafted theories as sufficient proof of the way the economy works. Well, I just came across a 2021 paper by Glandon et al. that has some interesting updates on what’s going on in the field:

We find that over the past 40 years there has been a growing emphasis on increasingly sophisticated quantitative theory, such as DSGEs. Papers employing these methods account for the majority of articles in macro journals. The shift towards quantitative theory is mirrored by a decline in the use of econometric methods to test economic hypotheses. Microeconometric techniques have displaced time series methods, and empirical papers increasingly rely on micro and proprietary data sources.

Now, this language makes it sound like macro is getting less empirical over time, because people aren’t testing macro models much anymore. But in fact, it means the field is getting more empirical, because it’s shifting from macro to micro data.

Let me explain a bit how this works. In the 80s, macroeconomists would make a model of the whole economy, and they would see if it fit the aggregate time-series data — stuff like employment levels, inflation, GDP growth, and so on. But basically this always failed, because the economy is a very complex and difficult thing to model. So essentially macroeconomists gave up on the idea that their models would work as well as models in other fields anytime soon.

And after giving up on that, they went in two different directions. Some of them decided that the whole idea of forcing models to agree with data was pointless, and instead macroeconomic theories should simply be used as thought experiments to “organize our thinking”. This was a fairly nihilistic approach, in my opinion. Others decided to step back and take a more humble approach, testing the pieces of macro models against micro data. Eventually, the hope is that a better understanding of how companies and consumers behave will enable the construction of more realistic — and more empirically successful — models from the ground up.

The fact that macroeconomics is shifting from using time-series data to micro data is a positive sign, because it’s indicative of this shift to a humbler, long-term scientific approach.

Anyway, those are the five things this week. Here’s a bonus one from the comments section last week.

6. The green energy transition is real and it is very much underway

Via John Van Gundy, here is an article in MIT Technology Review about how global energy spending is shifting strongly from fossil fuels to renewables:

The International Energy Agency just published its annual report on global investment in energy, where it tallies up all that cash. The world saw about $2.8 trillion of investments in energy in 2022, with about $1.7 trillion of that going into clean energy…In 2022, for every dollar spent on fossil fuels, $1.70 went to clean energy. Just five years ago, it was dead even…Within clean energy, the vast majority of spending is going into renewables like wind and solar, grid upgrades, and efforts to improve energy efficiency…

I’m really excited to see how fast money is moving into electric vehicles: spending went from $29 billion as recently as 2020 to an expected $129 billion in 2023. And spending on batteries for energy storage is set to double between 2022 and 2023.

Here’s the IEA’s report, which has many pretty graphs. On the climate front, I’m especially encouraged by the fact that capital expenditure in the oil and gas industry is collapsing; fossil fuel companies are increasingly just returning money to shareholders, which is what you do when you’re a declining sunset industry:

Meanwhile, clean energy investment is just going up, up, up.

Obviously there are subsidies involved, but as the report explains, a lot of this is just cost — renewables recently hit the threshold of cheapness where they can usually outcompete fossil fuels in many cases, meaning the purpose of the subsidies is increasingly just to make the transition happen even faster than it otherwise would.

Anyway, the energy transition is no hippie solarpunk mirage. It’s a huge real change that’s happening to our world right now, and it’s based on technological progress and innovation. Anyone who still doesn’t see the reality of that has their eyes closed and their fingers in their ears.

I like to consider myself a techno-optimist too, but I have to say I’m kinda glad VR isn’t panning out. It’s never been easier to throw two hours of your life away on a screen. I don’t want it to become easier and more immersive.

These roundup are substantial.