Solar is happening. Nuclear is (mostly) not.

The shape of our energy future is making itself known.

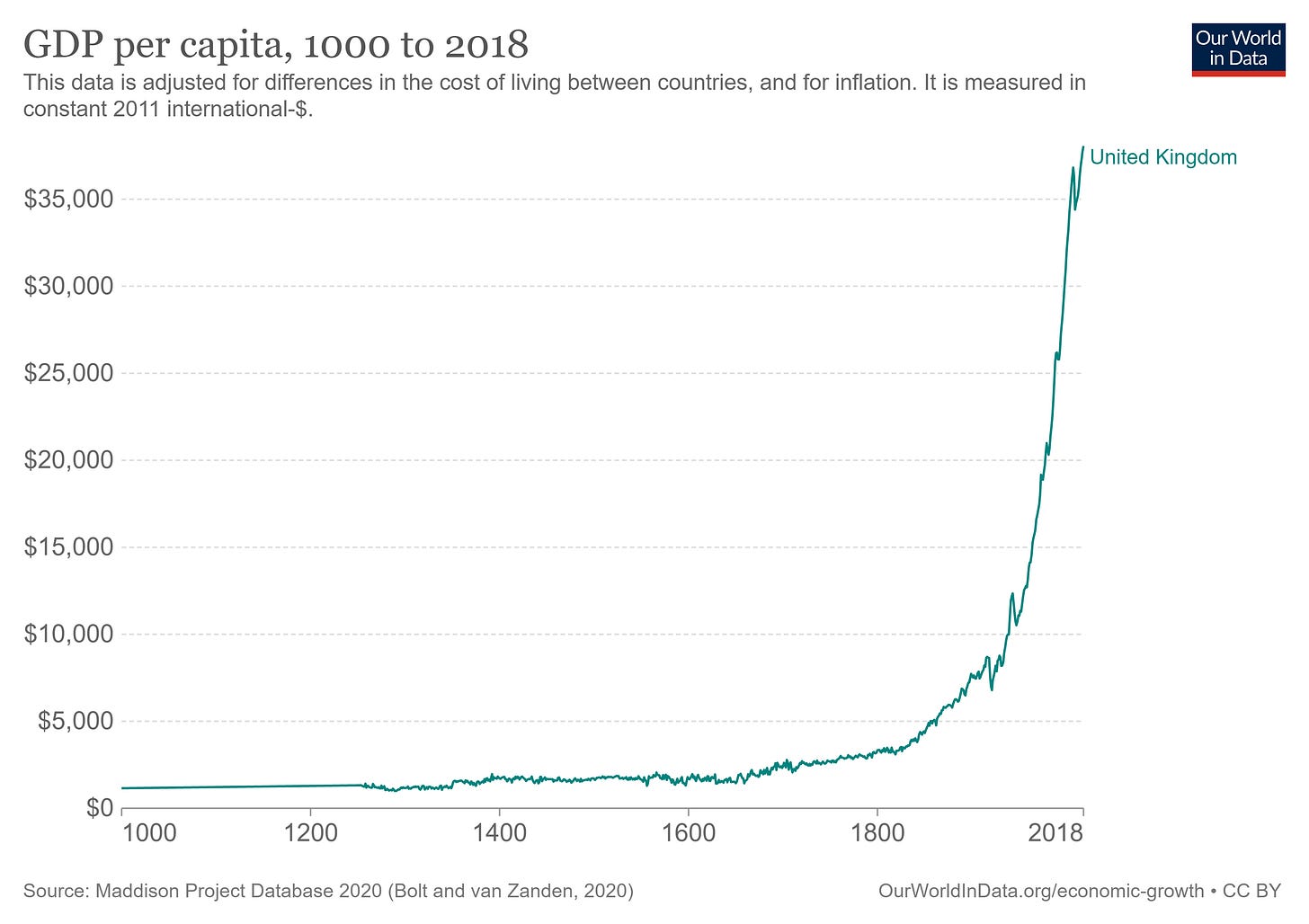

Along with agriculture, energy technology is one of the most fundamental building blocks of industrial civilization. Without the ability to capture and harness the energy of the natural world, humans are weak and powerless. It was really only once we began to harness the energy of fossil fuels on a mass scale in the 1800s that our species escaped grinding absolute poverty:

After the original advent of fossil fuels, there have been two — perhaps two and a half — major changes in the basic mix of technologies that we use to get the energy that powers our civilization. The first was when we started using a lot of oil for transportation in the early 20th century, and the second was when we started to use a lot of natural gas for heating and electricity in the late 20th century.

The “half” transition was the anemic rise of nuclear power. There was a lot of excitement about a switch to fission power after WW2, but by the 1990s the rise of nuclear had petered out at a pretty low level, except in a few countries like France.

Anyway, we are now in the foothills of an energy transition unlike any we’ve seen since the advent of coal power itself — a wholesale switch away from the fossil fuels that powered industrialization. This is happening for two reasons. One is climate, but the other, perhaps even more important reason is cost. Fossil fuel technologies are mostly mature, and as we exploit the easiest deposits of oil, coal, and gas it becomes more expensive to get out the harder stuff. But renewable energy — especially solar — has become so stunningly cheap that it has started to become much more economical than fossil fuels in many areas and for many applications. It’s looking more and more like fossil fuels are industrial civilization’s “starter pack”, and that renewables are a more permanent foundation for society’s material wealth.

When you say this on social media, you’ll tend to get a lot of pushback. A number of people loudly and angrily claim that renewables will never be able to power our society, and are only competitive with heavy government subsidy. The arguments for this deeply misinformed position range from real but solvable issues to empty knee-jerk slogans and blatant scientific and economic misunderstandings. And they’re often paired with the assertion that only nuclear power can be the energy source of the future.

Out there in the real world, however, businesses and countries around the globe are building solar power for all they’re worth. Nuclear, meanwhile, has stalled out. These developments are not due to governments putting their thumb on the scale for unaffordable unworkable renewables, as renewable opponents claim. Indeed, government regulation is the main remaining obstacle to the renewable energy transition, while new nuclear will need heavy financial assistance from government.

We can now pretty clearly see the shape of the energy transition to come, and it’s being driven less by policy than by the pure hard logic of technological innovation, capabilities, and costs. That’s why true technophiles — those who love the idea of human inventiveness and intellect gaining us mastery over our world — ought to love and embrace solar power.

I like nuclear, but I’m pessimistic about its future

I am a pro-nuclear guy. Nuclear power is cool. France’s big push for nuclear power was obviously a major success, reducing their carbon emissions and leaving them much less dependent on Russian gas. I think that despite the nuclear disasters at Fukushima, Chernobyl, and elsewhere, nuclear power is basically safe, and that the environmental concerns about waste disposal are overblown. I’m extremely glad that California might be keeping open its nuclear plant at Diablo Canyon, and I think it’s an absolute disaster that New York closed its plant at Indian Point. I think Japan should restart its nuclear reactors, and Germany should abandon its insane plan to shut down its own.

Nuclear power, to put it simply, is good.

That said, I think a hard-nosed look at the evidence shows that nuclear — or at least, fission — is not going to be our main source of energy when we transition away from fossil fuels.

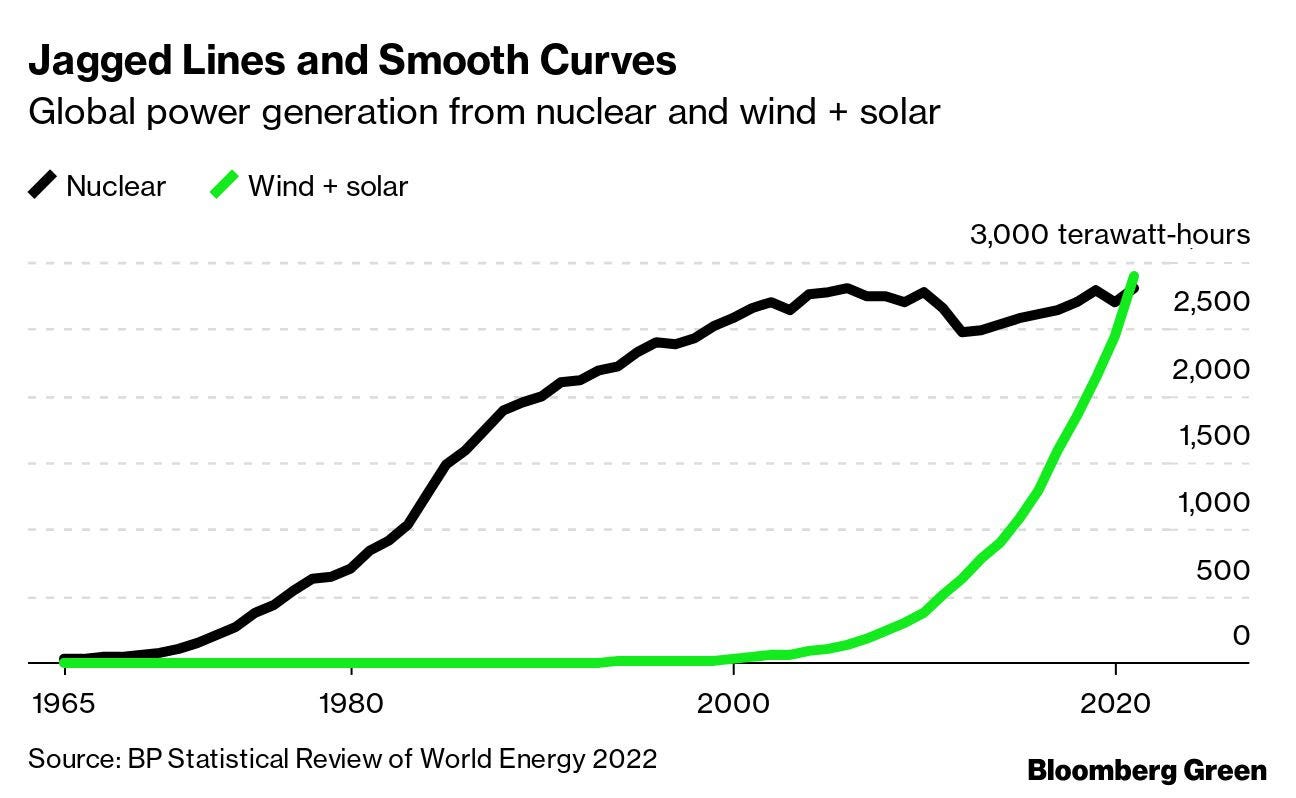

Here is a startling graph of nuclear being overtaken in our energy mix by solar and wind:

This graph is global, not just the U.S. That suggests that the flatlining of nuclear power isn’t due to the perverse politics of any one nation.

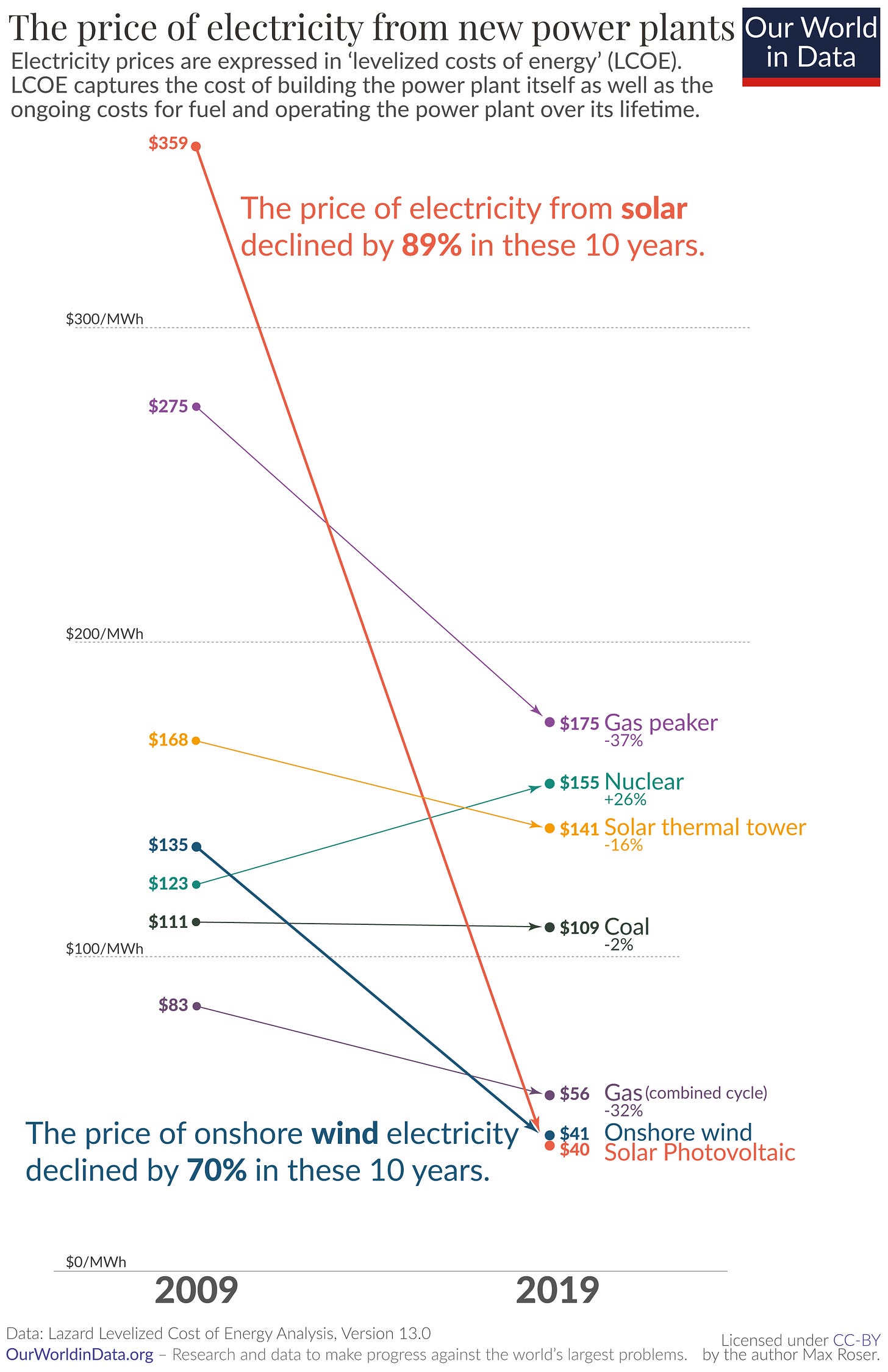

The real culprit is costs. During the 2010s, most types of power got cheaper, driven mostly by learning curves — the more we built, the cheaper it got to build even more. But nuclear, alone among energy sources, got more expensive:

This “negative learning curve” is directly visible when we look at France’s big nuclear build-out. Over the 1980s, Arnulf Gruber documented how as France built more and more nuclear, the costs of each new kilowatt of power soared. An MIT team found that although some of this was due to tightening safety standards, a big chunk was due to declining labor productivity — in other words, for some reason, nuclear keeps getting harder to build as we build more.

Nuclear proponents argue that the “tightening safety standards” portion of this cost increase was unnecessary — the result of irrational human fear of nuclear. And sure, maybe they’re right. But it keeps happening in every country. It’s possible that irrationally excessive human fear of nuclear power is a universal thing, but if so, that should make you less optimistic about nuclear’s future — it means that the safety regulations imposed by governments are a common, stable political-economic equilibrium. This explains why the lion’s share of new nuclear in the world is being built in China, a highly authoritarian country with notoriously lower concern for the health and safety of its citizens. But even in China, people do care about their environment, and there’s no reason to expect Chinese people to be more rational than others about nuclear risks. So even there, I’m pessimistic about nuclear’s long-term future.

There’s a second fundamental problem with nuclear besides cost. It’s cost structure. The vast majority of nuclear costs are up-front sunk costs — the plants are hideously expensive to build and pretty cheap to run. Additionally, nuclear plants are very, very large — a single nuclear plant in Georgia is now forecast to cost over $30 billion (in comparison, the Inflation Reduction Act’s entire annual subsidy for green technology is about $38 billion a year).

This cost structure creates two problems. First, it’s just hard to find the money — who has $30 billion sitting around ready to invest in a single power plant? And second, it creates huge risk — if new technologies become much cheaper during the 40-year life of a nuclear plant, the price of electricity will go down and the project’s backers will never be able to make back their investment. 40 years is a very long horizon over which to make such a risky bet.

This is why, traditionally, nuclear plants have required heavy financing, loan guarantees, and other assistance from the government. This is as true in the U.S. as it is in other countries, and it was true way back in the 50s and 60s, well before environmentalists started freaking out about nuclear.

The nuclear power industry has hoped to solve this by developing small modular reactors. These would not change the all-up-front nature of nuclear costs, but they would allow it to be broken up into smaller chunks that could — at least in theory — be handled by the private sector. A company called NuScale is leading these efforts.

Unfortunately, financing even these projects is proving very difficult. Ars Technica reports:

[T]he leading proposal for the first NuScale plant is running into the same problem as traditional designs: finances…

Typically, a nuclear plant is either producing or not, but the modular design allows the Carbon Free Power Project to shut individual reactors off if demand is low.

But keeping a plant idle means you're not selling any power from it, making it more difficult to pay off the initial investment made to produce it and adding to the financial risks. Further increasing risk is the fact that this is the first project of its kind…

According to one report, the US Department of Energy had originally planned to purchase the first reactor for research use, then turn it over to [the private sector]. But now, the goal is apparently for the DOE to provide an annual supplement of about $130 million a year for a decade. However, that would be dependent upon annual renewals of the funding by Congress during that decade, which is yet another risk. Separately, to reach a target price for the power that is expected to be competitive with natural gas, the project has been made larger and its completion delayed by three years.

That has apparently been scaring off some utilities that had signed up for a slice of the project…With the changes in price and funding, a number of those utilities are dropping out.

In other words, even with this new modular technology — the great hope of the U.S. nuclear industry — we’re seeing the same old pattern. Private companies are unwilling to pony up the cash and take on the huge risks involved, meaning government has to step in and carry the project on its back.

We can thus pretty clearly see the future of nuclear power in our energy mix. And it is a very modest, government-dependent future. We are probably going to need some modest amount of nuclear in order to shore up the intermittency of renewables (though much less than nuclear boosters think). But it is going to be absolutely pulling teeth to get these built — this is not a situation where the government can simply deregulate and watch nuclear plants spring up around the country. Our government is going to have to shell out big bucks to support nuclear every step of the way.

This is not the future I would have liked for nuclear. But looking at the technological and economic facts, I just don’t see any other plausible scenario.

Solar is for real, despite the problems

I’m pessimistic about nuclear power, but I’m strongly optimistic about solar power. The renewable energy opponents that swarm on social media dismiss solar out of hand, but they are all wrong to do so.

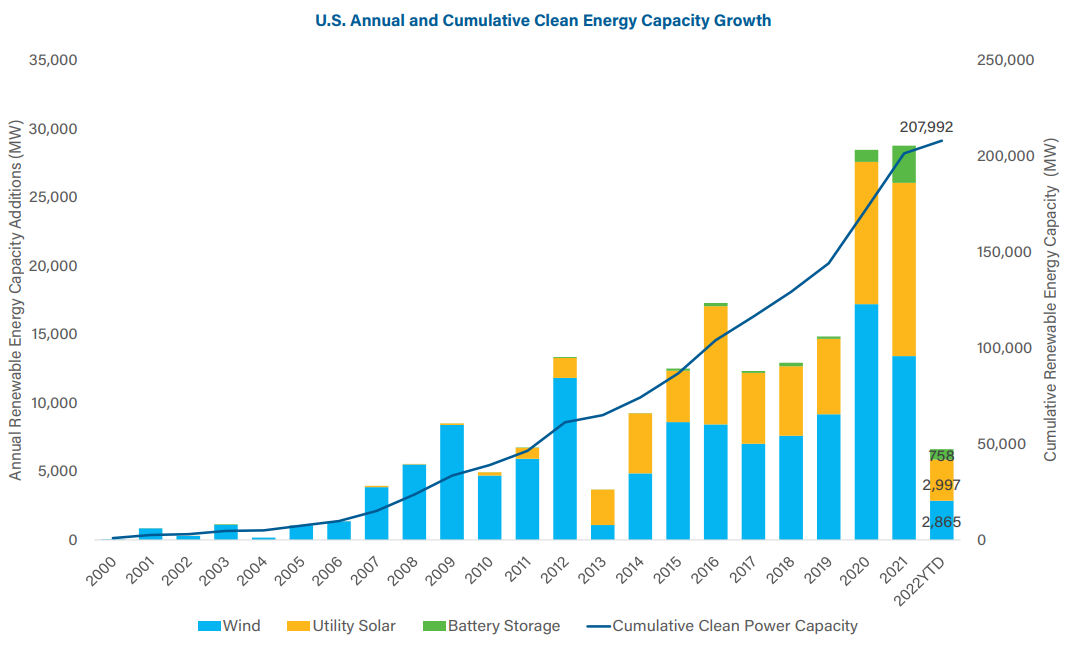

First of all, we need to simply look at facts on the ground. Here’s a chart from back in May showing just how fast renewable installation has been accelerating in the U.S., and how solar is increasingly taking over from wind:

Solar and wind continue to rise steadily as a percent of U.S. electricity generation, even as coal and gas both decline:

Even Texas, headquarters of the oil industry, is getting in on the action.

And, crucially, the numbers are also going exponential at the global level:

This means that just like the nuclear stagnation, the rise of solar is not being driven by local political factors — environmental activists, meddling leftist politicians, or whatever. China, which ruthlessly suppresses its activist movements and focuses relentlessly on economic growth and national power, is building so much solar that it’s now worried about eating up productive farmland! If China, which is perfectly willing to build nuclear plants, is building solar at breakneck speeds, you know it’s not some kind of inefficient green boondoggle — it’s for real.

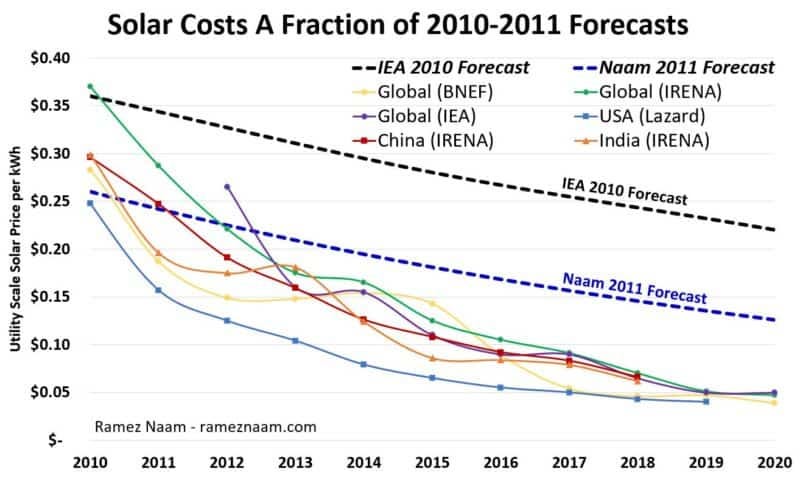

The reason solar is for real is simply that it has declined a ton in cost, as shown in the graph above. Much more than wind, much more than natural gas, solar is subject to a powerful learning curve — the more we build, the cheaper it gets. Here, via the excellent Ramez Naam, is a picture of how solar has gotten cheaper much faster than even the most starry-eyed optimists dared to predict:

The people who confidently assure you that solar is too expensive to be feasible without government subsidies, therefore, are blowing smoke. Either they haven’t bothered to look at the evidence in a decade, or they ignored it for some dogmatic ideological or political reason.

Now, a reasonable critique of solar power is that it’s intermittent. Night happens. Rain happens. Clouds happen. Winter happens. The sun isn’t always shining, so we need a combination of energy storage and backup power to make sure we can always keep the lights on. Obviously, the people installing solar at breakneck speed all over the world have thought of this.

Over the course of a day, batteries are fine for energy storage (and yes, we have the minerals to build them). But as David Roberts explained in our interview earlier this year, storing energy from summer to winter can’t really be done with batteries; it will require different solutions. The most likely solution, according to Roberts, is hydrogen.

But note that even without a seasonal storage solution, we can overbuild solar, so that even in the dark winter months we get enough power to keep everything running. Solar is just getting so damn cheap that we can build more of it than we need in the summer. I’ve seen estimates that we would have to overbuild by a factor of 4 to do this, but with solar costs going down by 89% a decade, that doesn’t seem out of reach in the slightest.

In other words, just keep building more solar, it’ll be fine.

There is one problem with solar in the U.S., however, that will be difficult to overcome — government regulation. In recent years, local NIMBYs — including some environmentalist groups who really should know better — have used the National Environmental Policy Act and the California Environmental Quality Act to block the building of solar plants. Just as with housing and transportation, the future of energy in the U.S. is under threat from an unholy alliance of parochial anti-development forces and misguided government regulation.

In other words, solar, not nuclear, is the technology that just needs government to get out of the way. The streamlined permitting for renewable energy projects that Congress may enact as a side deal to accompany the Inflation Reduction Act is a crucial step toward getting the government out of the way.

But as with housing and transportation NIMBYism, this is mostly a U.S.-specific problem. Globally, the future of energy technology is being determined not by politics, but by the cold hard facts of technological progress. We successfully figured out ways to make solar really, really cheap. We did not figure out ways to make nuclear really, really cheap. So as a species, we will go with the solutions we found, rather than the solutions some of us wish we had found.

This is exactly right. Only one point to add - solar panels are technically a semi-conductor and operate like computer chips in reverse - instead of converting energy into information, they convert information (photons) into energy. But they benefit from the equivalent of Moore’s law (Swanson’s law in solar speak; cost drops by 20% as shipments double). The 75% drop seen from 2009-2019 is consistent with solar’s history.

What makes the solar’s Moore’s law different is that is smashed past a key benchmark sometime during COVID - it at its most expensive became cheaper than fossil fuels at their cheapest. We have no alternative to computer chips, so as Moore’s law chugs along for them we just seem incremental benefits. But imagine that we had an alternative information generator than computers that our society was based around - and suddenly computers became faster and cheaper than that - we’d never stop talking about it. That’s essentially what has happened with solar. The price drop is same as it ever was, but now it has smashed past the floor fossil fuels must rest forever upon.

If we see more shipments than expected because of this, then the 75% price drop anticipated over the next 10 years represents a very conservative baseline. Costs so far appear to be pegged to shipments, and those will increase drastically if it is a cheaper energy source than all the alternatives.

I just saw that Maryland is starting a Solar Canopy grant program in 2023 for parking structures

https://energy.maryland.gov/business/Pages/incentives/PVEVprogram.aspx

This looks like the a good direction. Nuclear has benefits in the short term to wean us off using coal. I an optimistic it will stick around somehow.